Pronomina Lization (An Old and Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAM058 |

| Author: | D. N. S. Bhat |

| Publisher: | Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1978 |

| Pages: | 118 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 140 gm |

Book Description

In spite of a brisk activity in the field of linguistics in India during the last quarter of a century, works dealing with the theoretical aspects are few and far between. The major part of the activities of Indian linguists is devoted to recording and describing Indian languages according to one or the other model in vogue and in writing comparative and contrastive grammars of both literary and un-written languages of the country. The present essay of Dr. D. N. Shankar Bhat, Pronominalization—a Cross-Linguistic Study, is a welcome addition to the few works which are devoted to the elucidation of some important linguistic feature with theoretical implications, along lines generally followed these days within the frame-work of Transformational-Generative and Semantic approaches to linguistics. Such an approach has greater relevance to the understanding of languages in depth and it is nearer the philological and literary studies of the nineteenth century. Instead of simplifying the purely formal grammatical machinery of a language by reducing it to the minimum by neglecting the semantic complexity associated with it, it is far more important to face the complexity of the thought-contents of language and the ways in which it is expressed in natural languages. Such an approach is essential if one wants to compare different types of languages for the ways they adopt in dealing with some basic and recurrent ideas forming the core of linguistic communication. Whether such attempts can lead to the discovery of substantive linguistic universals, only attempts of this type can decide.

Dr. Bhat has chosen for his study the ideas associated with the process of pronominalization current in a number of languages like Kannada, English, Hindi, Japanese and some others to a limited extent. He attempts to clarify with greater precision ideas like reflexivity, identity of reference, anaphoric and pragmatic reference, reciprocity and some others usually expressed by the use of pronominal forms, as a prerequisite for a detailed comparison between languages of different historical origins.

This study has brought out a few interesting features of languages as such. We perceive that natural languages distinguish these concepts differently and group them in a different manner. The means used to express them are also diverse and cut across the traditional divisions of grammar like morphology, syntax and vocabulary. The author’s suggestion to postulate a two-fold double articulation in languages appears to be essentially correct, though one may draw the boundary line for the second double articulation between sentence as a syntactic unit and proposition as a semantic unit, instead of placing both of them on the same side of the line. In such a case, it may not be much different from the distinction between syntactic and semantic structures, though differently defined. All the same, many of the distinctions emphasised by Dr. Bhat are appealing and thought-provoking. Personally I enjoyed the reading of the monograph and imagine that many others will find it equally enjoyable.

1.1 Phonetic and semantic features: a difference:

There is a crucial difference between the occurrences of phonetic and semantic features in natural language: if we compare ten or twenty distinct languages and make an overall list of phonetic features occurring in them, the list would be such that the speaker of any one of those languages would be expected to master (or even to be aware of) only a small sub-set of that overall list. That is, each of those languages would be “selecting” only a small portion of the very large list of humanly produceable phonetic features. Each would be concerned only with this selected portion; the non-selected portion would be irrelavent as far as that particular language is concerned. Thus, phonetic features such as retroflexion, palatalization, aspiration, glottalization, implosion, etc. are non-universal in their distribution. Each of them is found only in a sub-set of the languages of the world, and is hence irrelevent for the functioning of the languages which do not belong to that sub-set.

The semantic features, on the other hand, are completely different from the phonetic ones in this particular respect. If we make a similar comparison of ten or twenty distinct languages and produce an overall list of semantic features occurring in them, the list would be such that the speaker of any of these languages would be expected to be capable of expressing every single semantic features occurring in that list. That is, languages do not “select” semantic features as they select phonetic features. Rather, they have an in-built capacity to express any semantic feature that can be thought of by a human being. Hence no semantic feature can be considered to be “irrelevant” for a given language.

This unlimited capacity of natural languages to express anything that is thinkable is considered to be one of their most important characteristics. It has been termed the “principle of effability”. As pointed out by Katz (1972:19), “one does almost inevitably find a sentence in his language to express what he wants to say, even though the process may not always be easy and the final choice may not always be the best way to say it. Failure means the person is not sufficiently skilful in exploiting the richness of his language rather than that the language in not rich enough in expressive power”.

1.2 Two double articulations:

How does a language build such a capacity to express an unlimited number of semantic features (or meaning distinctions) with the help of a limited (and rather small) number of phonetic features? It would be shown below that there are in fact two different “double articulations”, built one upon the other, which jointly help language to develop such a capacity.

When linguists refer to the occurrence of double articulation (Martinet 1962:24) or duality of patterning (Hockett 1958:574) in language, they generally appear to indicate the first double articulation, namely the one between sounds and meanings. Even though some sounds in a language might be directly connected with meaning (as is the case with sound symbolism, onamatopoeia, imitative, etc.), much of the meaning is connected only indirectly with sounds. Sequences of sounds are made to represent morphemes or lexical items, and these items are then directly connected with meanings. There is thus a double articulation in the indirect connection of sound to morpheme and morpheme to meaning.

Notice, however, that all the meanings that one can express with the help of a language are not directly available from morphemes or lexical items. It is very well known that the meaning of a sentence is not the sum of the mening of the morphemes or words occurring in it. Because, if that were the case, English sentences such as ‘My wife has a new dog, My new wife has a dag, My new dog has a wife, etc. would have identical meanings (Leech 1974:126). We know very well that these sentences have different meanings, and the only way to account for this difference is to set up a second double articulation, namely an indirect an indirect connection between morphemes and meanings through an intermediary unit called sentence or proposition.

Thus a language develops its sound-meaning relationship through three different connections: Some meanings are directly expressed by sounds (sound symbolism and onamatopoea), some indirectly through morphemes or lexical items (first double articulation), and the rest through syntactic structures (second double articulation). The starting point, namely the sound system is a closed one, but the set of morphemes forming the intermediary link of the first double articulation is an open one. It is also comparatively very much larger than the list of sounds. The second double articulation is built upon this “open” list of morphemes and the list of syntactic structures (or sentences) which forms the inter-mediatary link of this second double articulation is therefore even more “open” and much larger than the morphemic list (i.e. lexicon). The capacity of a language to express an unlimited number of semantic distinctions is based upon this complex set up.

1.3 Testing the effability principle:

Do all languages really have this capacity to express an unlimited number of semantic features? One way to test this effability principle, I believe, is to take a small area of meaning such as pronominalization, definitization, negation, question formation, time and aspect indication, case marking, etc., and to make an overall list of meaning distinctions occurring in that area through a cross-linguistic study. If languages are really affable in nature, it should be possible for any given language to express––either through its lexical items or through its syntactic structures––all the meaning distinctions included in such an overall list.

The present monograph is an attempt to conduct a test of this nature. I have examined in it the topic of pronominalization from two different points of view: Firstly, I have tried to see how the meaning distinctions generally included under this topic, such as the reflexive, reciprocal, anaphoric, etc. are expressed by various languages—i.e. how these languages resemble or differ from one another in selecting a lexical or syntactic device (which might be pronominal or non- pronominal) for expressing these meaning distinctions.

Secondly, I have examined the occurrence of various types of ambiguities in the use of these devices, and have tried to see how a given language could remove those ambiguities. Since these ambiguities are “thinkable” (otherwish they would not be recognized as ambiguities) a language, if effable, would be expected to have devices for disambiguating them.

I have based this study partly on an examination of the published grammars of about one hundred languages. Since these grammars were good, bad, or indifferent (mostly indifferent) to the topic under study, my conclusions based upon them would hardly be anything but tentative. It would be clear from the following pages, however, that I did succeed in bringing out certain very pertinent points regarding pronominalization on the basis of this cross-linguistic study. Hence, even if “superficial”, such studies do have their own relevance and importance for the study of language.

I have supported the above cross-linguistic study of published grammars with a more thorough study of Kannada (Bhat: forthcoming), a Dravidian language spoken in southern India. Since this is my first language (mother tongue) I could be more thorough and definite regarding its expressive power. This latter study was especially helpful in my analysis of ambiguous usages and the corresponding disambiguating devices. I have not so far come across a single meaning distinction that cannot be disambiguated by Kannada. I believe this to be true of all other natural languages, and hence I tentatively conclude that natural languages do posses effability as one of their most important characteristics.

It may be noted here that the approach taken by me in the formulation of the above test is somewhat different from the one generally used by linguists in their study of language. Even though grammars are supposed to have the power to “generate” sentences, linguistic studies generally deal with “interpretations” of sentences or of their deep structures, or of “projection rules” for meaning. In the present monograph I start with a series of meaning distinctions collected through a cross linguistic study and try to see how a given language can “express” them by using various lexical or syntactic devices. I also examine the various ambiguities that could arise while these devices are used, and try to see how the language can express the meaning distinctions underlying those ambiguities through additional devices.

Thus the emphasis in this monograph is throughout on the capacity of a language to “express” meaning distinctions through its sentences, rather than on the capacity of a linguist to formulate rules for the “interpretation” of such sentences. I believe that this shift in the viewpoint has brought out certain interesting revelations regarding the topic under study.

| 1. | Introduction | 1 |

| 1.1 | Phonetic and semantic features: a difference | 1 |

| 1.2 | Two double articulations | 2 |

| 1.3 | Testing the effability principle | 3 |

| 2. | Aspects of Pronominalization | 6 |

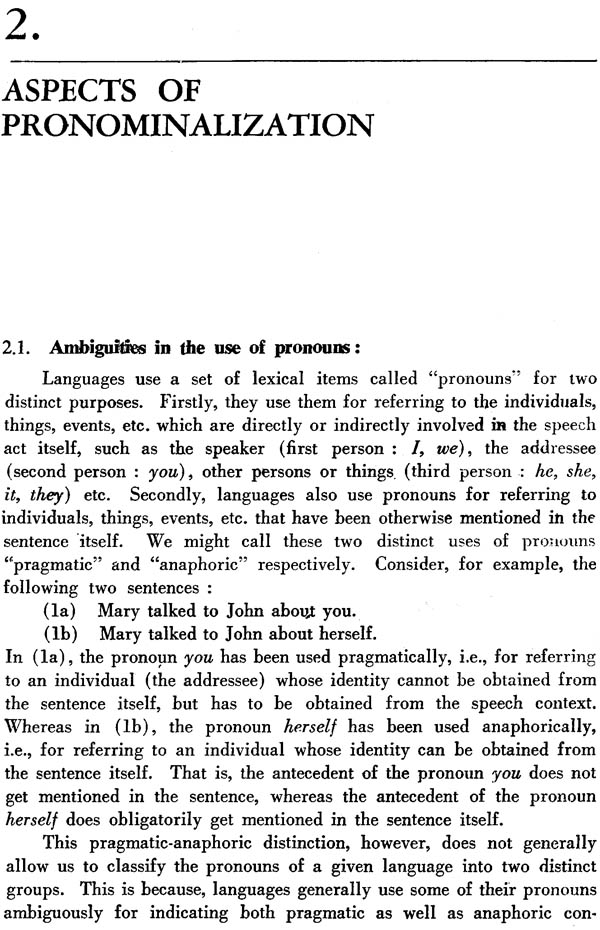

| 2.1 | Ambiguities in the use of pronouns | 6 |

| 2.2 | Two kinds of anaphoric use | 8 |

| 2.3 | Scope of complex sentences | 9 |

| 3. | Reflexive Meaning | 12 |

| 3.1 | Nature of the reflexive meaning | 12 |

| 3.2 | Ways of indicating the reflexive meaning | 14 |

| 3.3 | Simple sentence condition | 16 |

| 3.4 | Relational hierarchy | 17 |

| 3.5 | Subject-antecedent condition | 19 |

| 3.6 | Pragmatic-anaphoric ambiguity | 21 |

| 3.7 | Two types of reflexive meaning | 24 |

| 3.8 | Extension of the reflexive device for indicating exphasis | 25 |

| 3.9 | Distinguishing between reflexive and emphatic devices | 28 |

| 3.10 | anaphoric use of reflexive pronouns | 31 |

| 3.11 | Relationship of possession | 32 |

| 3.12 | Passive use of reflexive verbs | 35 |

| 3.13 | Reflexives as reciprocals | 38 |

| 3.14 | Invariability of a reflexive argument | 38 |

| 4. | Reciprocal Meaning | 40 |

| 4.1 | Nature of the reciprocal meaning | 40 |

| 4.2 | Identity in reciprocal meanings | 41 |

| 4.3 | Ways of indicating the reciprocal meaning | 42 |

| 4.4 | Reciprocals in Kannada | 44 |

| 4.5 | Subject antecedent constraint | 45 |

| 4.6 | Distinguishing reciprocals from reflexives | 46 |

| 4.7 | Reflexives used as reciprocals | 48 |

| 4.8 | Nature of the reciprocal marker | 49 |

| 4.9 | Plurality of the arguments | 50 |

| 4.10 | Reciprocal and comitative meanings | 51 |

| 5. | Special Anaphoric Pronouns | 52 |

| 5.1 | Two types of ambiguity | 52 |

| 5.2 | SAP in Kannada | 53 |

| (a) Subject antecedent constraint | 55 | |

| (b) Experiencers as exceptions to the constraint | 56 | |

| (c) Awareness of the antecedent | 57 | |

| (d) First and Second person referents | 59 | |

| (e) Absence of gender distinction | 59 | |

| (f) SAP in simple sentences | 60 | |

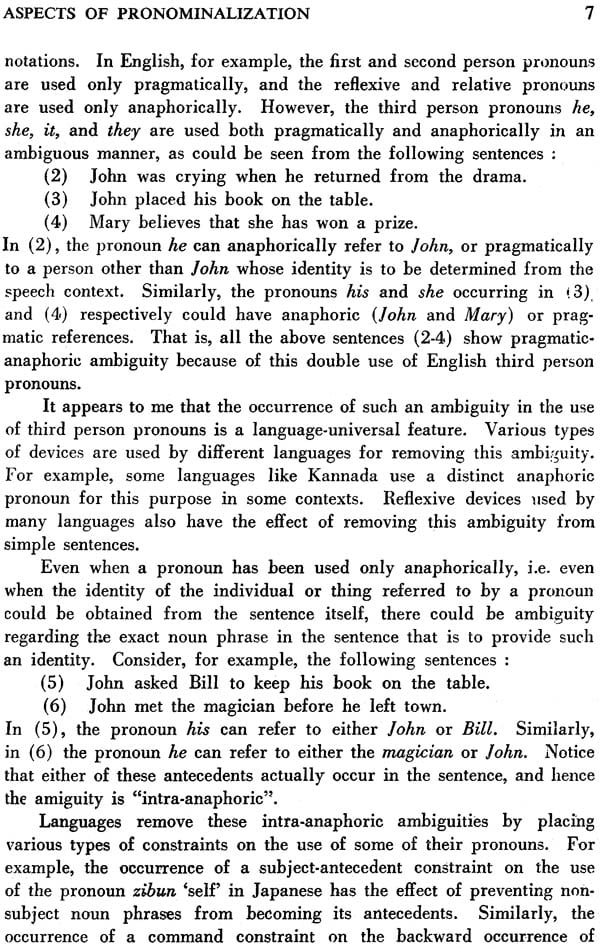

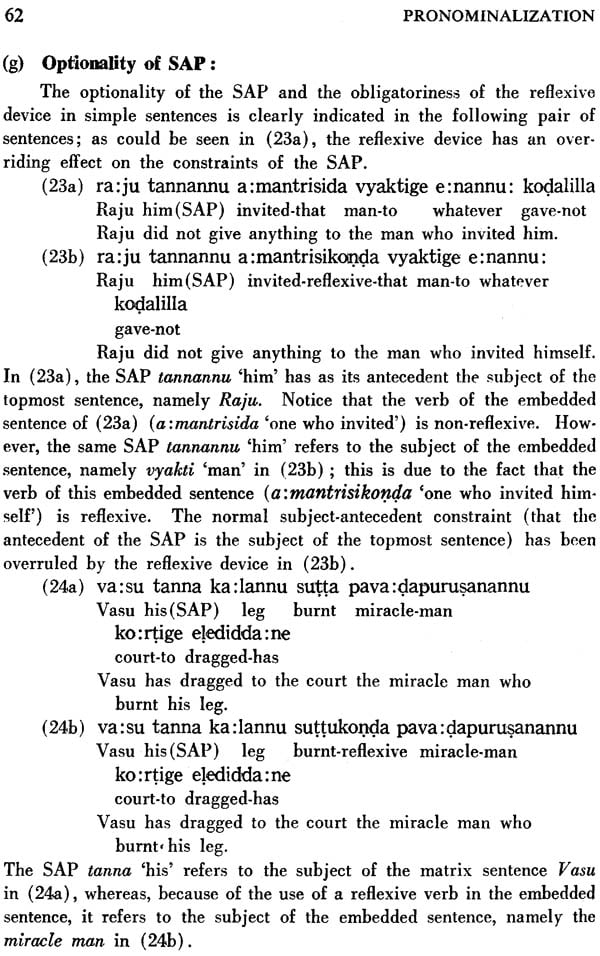

| (g) Optionality of SAP | 62 | |

| (h) Constraints based on verbs | 63 | |

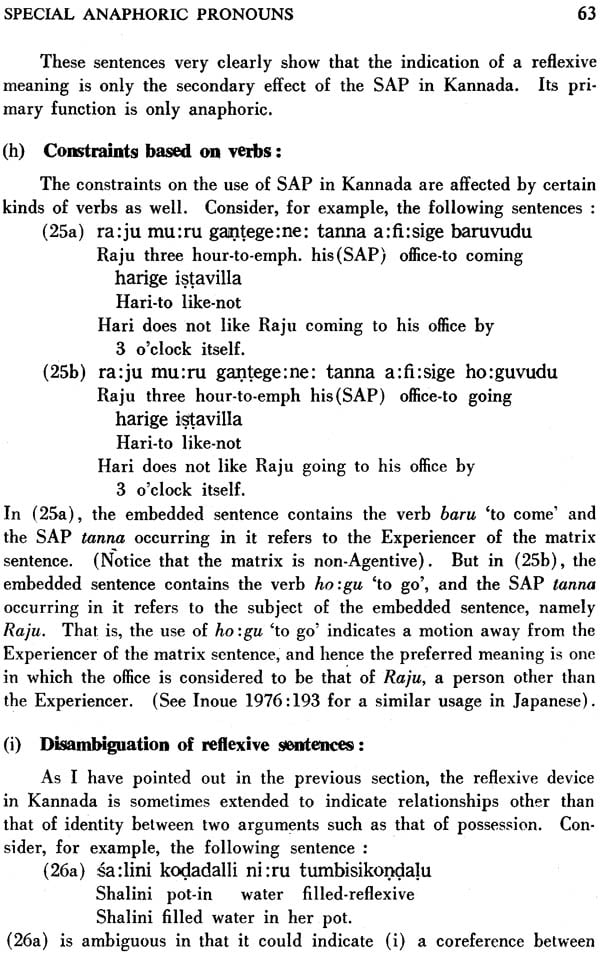

| (i) Disambiguation of reflexive sentences | 63 | |

| (j) Backward occurrence of SAP | 64 | |

| 5.3 | Japanese zibun 'self' | 66 |

| (a) Zibun as a reflexive pronoun | 66 | |

| (b) Zibun as an SAP | 67 | |

| (c) Constraints on the use of zibun | 69 | |

| (d) Command constraint | 69 | |

| (e) Zibun with emotive verbs | 70 | |

| (f) Optionality of zibun | 70 | |

| (g) Dialectal difference | 71 | |

| 5.4 | Hindi ap 'self' | 71 |

| (a) Ap as a reflexive pronoun | 71 | |

| (b) Ap as an SAP | 73 | |

| (c) Clause-mate constraint on the use of ap | 74 | |

| (d) Optionality of ap | 75 | |

| (e) Relative depth constraint | 76 | |

| (f) Backward occurrence of ap | 77 | |

| 5.5 | Fourth person of Eskimo | 78 |

| 5.6 | Referring pronouns of N.E. Africa | 79 |

| 5.7 | Faroese seg | 80 |

| 6. | Relative Coreference | 81 |

| 6.1 | Distinctness of the relative coreference | 81 |

| 6.2 | Ways of indicating the relative coreference | 82 |

| 6.3 | Two kinds of ambiguity | 83 |

| 6.4 | Ambiguity resulting from deletion | 84 |

| 6.5 | Certain general tendencies of relativization | 85 |

| 7. | Coreference in Quoted Sentences | 89 |

| 7.1 | Two different pragmatic contexts | 89 |

| 7.2 | Ambiguities in quoted sentences | 90 |

| 7.3 | Special pronoun neh of Mambila | 91 |

| 7.4 | Direct and indirect quotations | 92 |

| 7.5 | Reporting the thought of an individual | 93 |

| 8. | Conclusion | 95 |

| 8.1 | Limitations of this study | 95 |

| 8.2 | Implications for the study of language universals | 96 |

| References | 99 | |

| Index | 103 |