Tyagaraja - Lyric to Liberation

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAS624 |

| Author: | Sudha Emany |

| Publisher: | Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2019 |

| ISBN: | 9788120842595 |

| Pages: | 232 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 340 gm |

Book Description

A Story Retold

Tyagaraja: Lyric to Liberation is first and foremost a reverential narrative of the life of an unusual person in whom the triple streams of bhakti, music, and saintliness coalesced. In Tyagaraja, the streams were fed by his remarkable ability to zero in on the single aim of liberation through a skilled deployment of language. No other composer before or since exhibited the range of emotions, sensibilities, or attitudes toward the Godhead symbolized, in his case, as Rama. Every human endeavor, short of the goal of self-realization, was a wasted effort. Rama was as real to him as any other human being with whom he interacted. The devotee and the Lord were not separate. It was this unshakeable conviction that informed the entire output of the poetry that was the collection of his songs, whether we place their number at 700 or 24,000. His lyrics were not mere exercises in musical composition or saintly spirituality: they were the man himself.

Through it all, the man that was Tyagaraja-the stem disciplinarian, the gentle soul, the loving friend, and the humble devotee-comes across brilliantly. The book is at once entertaining, instructing, and exalting.

Sudha Emany, with Master’s in English from English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad, a diploma in violin from Potti sreeramulu Telugu University, Hyderabad, and a Diploma in Sanskrit from the Vivekananda Institute of Languages, Ramakrishna Math, Hyderabad, is uniquely qualified to write on the Sahitya (Lyrics) of the composer-singer-saint tyagaraja. She has taught English and Sanskrit at the Vivekananda Institute.

Italian traveller Nicolo Conti called it 'the Italian of the East.

Rabindranath Tagore affirmed that it was the sweetest among Indian languages.

Krishnadevaraya of Vijayanagar wrote that it was the best among regional languages.

Renowned poet Bharati used the epithet 'beautiful' to characterize it.

Kancherla Gopanna, a.k.a. Ramadas, used it in his poems and compositions.

And

Tyagaraja deployed it in his krtis to express the eternal anguish of the humans to return to their source, the Divine.

The 'it' in the above statements is the Telugu language, in which most of the words end in a vowel, as opposed to a language like English whose words generally end in a consonant. Italian words, too, end mostly in vowels or, where they don't, the speakers supply a suitable vowel to enhance their resonance. What fascinated an Englishman like Charles Philip Brown of the Indian Civil Service was the way Telugu words seamlessly dovetailed into each other in transitions and ended sonorously when the sentence ended. Native English speakers must have noticed the vivid contrast with their language in which, because of its morphology, the word-breaks jarred and the utterances ended abruptly unaided by a restful vocalic finality.

Language is an amazing human invention. It must have started when the second human being came into existence, whenever that was. It's a tribute to human genius that it is rule-bound and beautifully organized. It would be impossible to imagine a society where there is no language, even though philosophers tell us that the most effective kind of communication occurs not through language, but through silence. In reality, we cannot survive without the multipurpose tool of language. The saint uses it, as does the sinner. It helps makes peace, it makes wars. It is used to praise one and damn another. Shakespeare's Cali ban tells his mentor Prospero.

You taught me language, and my profit on 't

Is I know how to curse. The red plague rid you

For learning me the language.

Telugu appears to be intrinsically suitable for melodic expression. It has an infinite ability to borrow and 'naturalize' any Sanskrit word it needs for any reason. Every language of course has its 'genius.' Every language is sweet in its own way. It so happened that Tyagaraja used Telugu and exploited its innate features to the fullest extent like no other vaggeyakara.

Tyagaraja's compositions were mostly context-based, i.e. every one of his songs was composed to address a specific life situation. They were targeted. This was the major reason for the perfect fit of his language with his music. The word lyric implies that it is written to be performed to the accompaniment of the lyre, an ancient Greek stringed instrument. His lyrics ennobled his music, even as his music energized his lyrics.

Why Another Book on Tyagaraja?

Because Tyagaraja was multifaceted, with each facet skillfully cut and brilliantly polished. Each facet seamlessly fused into the whole diamond, whose light refracted a dazzling spectrum of divine music, pristine devotion, and saintliness of the highest order. He was at once a poet, musician, and saint sui generis. A devotee par excellence. A human being nonpareil.

And, because the information that is available on the greatest Carnatic musician of all time is in bits and pieces that are often mutually irreconcilable and inauthentic, ultimately traceable to the disorganized notes kept by Tyagaraja's own disciples. Be that as it may, as of now, there is no single book where a concise life story of the musician-saint is presented that could be read at a single sitting. This book also depends-as it must-on the scrappy information culled from multiple incongruous sources, but at least the main outline is narrated as a single continuous thread that includes the three ingredients of Tyagaraja's life, lyrics, and liberation, while not purporting to serve as a monograph on anyone of them.

It is said that, when goddess Kali was asked to distinguish among the stalwart Sanskrit writers Dandin, Bhavabhuti, and Kalidasa, she started by saying that the first was a poet and the second a scholar, and then tantalizingly paused. Kalidasa, who was waiting for an assessment of himself by the goddess, became impatient and demanded to know what she thought of him. She then paid him the ultimate compliment and declared, "You and I are one and the same.

Introduction

Tyagaraja was not just another musician. Neither was he just a composer. He was, as has been noted, equal parts composer, singer, and saint. The spiritual fragrance emanating straight from his heart and expressed musically in his lyrics set him firmly on the road to liberation. Not all musical writing can claim the same puissance, and neither do all composers who practice their craft primarily to please themselves care to be dropped at the doorstep of moksa.

This book is not a catalogue of events, or a chronology of dates, a treatise on musicology, or a resume of contemporary politics. It is a story retold yet again, so as to show the singer's gradual evolution from Tyagayya to Nadabrahmananda, through intense devotion into whose service both his music and his lyrics were pressed. Tyagaraja cruised the highways and byways of Carnatic music, and also paved them smoothly for those who followed him.

Thus our principal focus here is the lyrics, their language, its purport, and its effectiveness as a tool for liberation. Our ancients believed that the word in fact was mantra, an esoteric utterance that was capable of leading an individual to spiritual liberation.

To look at it another way: part of the fate that befalls great people is that many authors feel interested to write about them from their individual points of view. Often the result is like what happened when the blind men described the elephant. Each tackles, successfully maybe, a part of the topic, but no comprehensive analysis results.

While there are any number of publications on the music of Tyagaraja, the linguistic aspects of his lyrics have been scarcely touched upon. Undoubtedly, music, among all the performing arts, has a way of penetrating the soul and overwhelming our senses. That music derives not a little of its fragrance from the implicit and explicit sentiments couched in well-chosen and strategically deployed words.

Extreme care has been taken to ensure that all non-English words, phrases, and sentences are either relegated to footnotes or fully explained in the text, in an attempt to reach the widest possible audience. The work is a compact, non-technical, highly accessible introduction to the marvel that is Tyagaraja.

Is it any wonder that a musician who received the gift of the ultimate music manual Svaramava from its author Narada himself became a musician fit to sing for the gods? Or is it any wonder that one who received the inspiration for his very existence direct from the venerable Valmiki and an arch-devotee like Tulasidas attained sainthood?

His life story is every bit as interesting as the man himself, as engaging as his devotion, and as inspiring as his music. One never gets tired of reading about his total commitment to the Divine manifested as Rama and his interactions with Him on the one hand and the earthly rulers and good and bad humans on the other.

W. J. Jackson, in his compendious work on Tyagaraja, makes it a point to describe Tyagaraja's use of Telugu for his compositions and how he molded the language to express his deep feelings of devotion to the Divine:

Tyagaraja's songs display an ingenious use of language, the Telugu is compactly lyrical, deceptively simple, suggestively minimal, often with a flavour of urgency, yet not without a classical dignity and propriety. The sound of the words coincides with and is integral to the melody. This oneness of sound and meaning is characteristic of Tyagaraja's unique voice. His heartbeats were in Telugu, we might say.

It is said that the scholarly Muthuswami Dikshitar and the more reserved Syama Sastri achieved beauty through the cumulative build-up of repeated effects, as in discursive arguments; their works were articulated with style and careful diction and depend upon successive elaborations for their effect. In the traditional comparison, such works are said to be like coconuts which must be dehusked and cracked open and chewed rather laboriously before they release their rasa to be enjoyed and assimilated. The master lyricist Tyagaraja composed music which has flavour and impact, like grapes smashed on the roof of the mouth, their juice or rasa swallowed immediately, stimulating thirst for more.

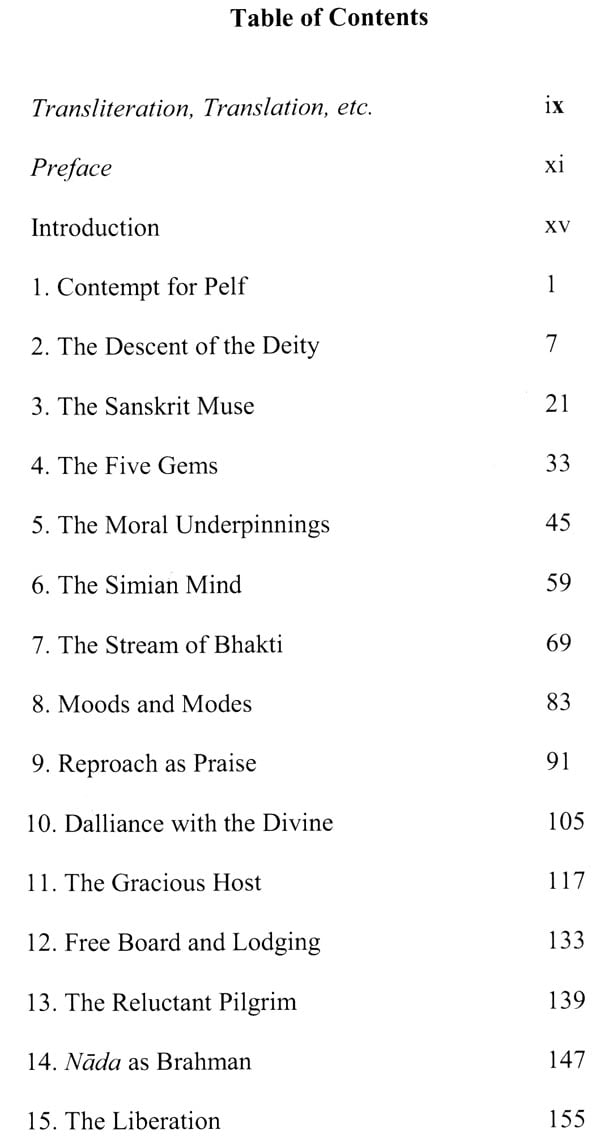

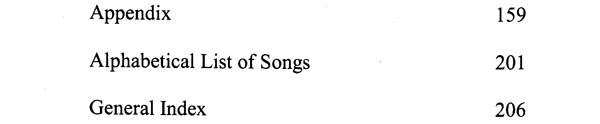

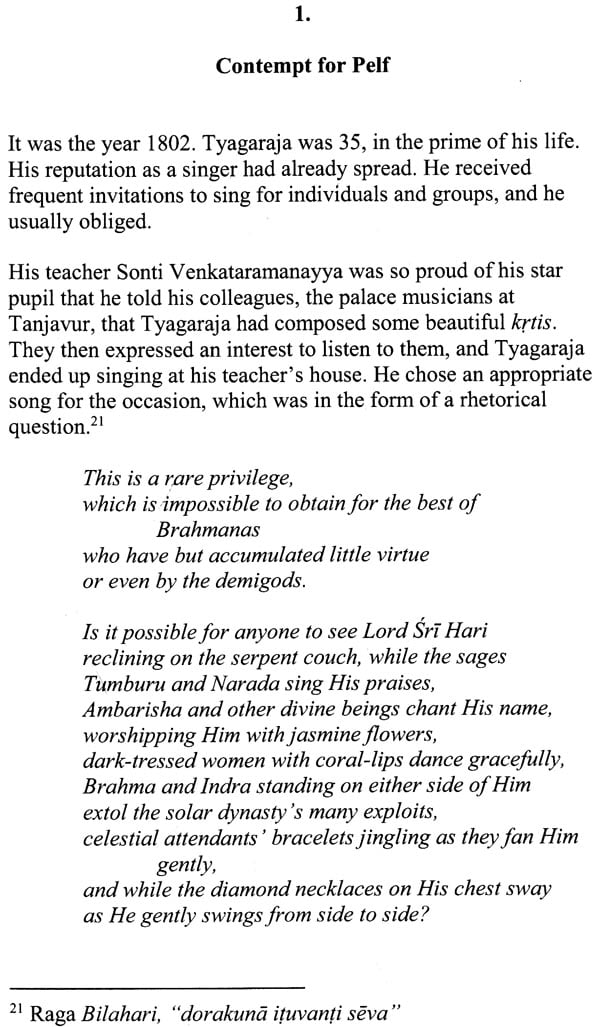

**Contents and Sample Pages**