Albert Einstein His Human Side

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAS184 |

| Author: | Swami Tathagatananda |

| Publisher: | The Vedanta Society of New York, USA |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 0960310460 |

| Pages: | 192 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 220 gm |

Book Description

"In this book on Einstein, characterized by brevity and depth of insight, Swami Tathagatananda discusses some of Einstein's biographical details, some of his ideas on science but all his essential ideas on life. His book will appeal both to those who want to understand Einstein and to those who want to understand life, and thereby alleviate their suffering. It will appeal both to the scientist and to the general reader. One can emulate Einstein's curiosity, his sense of wonder at life's mysteries and above all, rise above "the vanity of human desires and aims" with their disappointments, suffering and tragedies, this veritable "vale of tears," through unselfish work, service of others and a sense of the Supreme Intelligence pervading everything."

The first edition of my book, Albert Einstein: His Human Side, was published on January 24, 1993. My remarks in the Preface of that edition are included in this Preface to the second edition, which I have written with a more detailed explanation of Einstein's humaneness.

I admire Einstein's simplicity, his reverential attitude to the Supreme Principle, his utter lack of craving for material success, his sincere pacifism and above all his contemplative attitude. In these days of increasing violence it is very refreshing to think of his noble character.

We know Einstein as the greatest scientist since Newton, who in 1666 laid the foundation for the scientific theories that subsequently revolutionized the world of science. Einstein however, did not confine himself to the ivory tower of scientific research; his humane character took a lively interest in the diverse field of human welfare. The famed author of the series, Library of Living Philosophers, Paul Arthur Schilpp called him a "philosopher scientist." On the other hand, William Hermann who called him a "poet," claimed that Einstein was too vast and multifaceted a personality to be pigeonholed in one category.

Einstein was deeply concerned about the fact that science and technology have released an uncontrollable power so great that it is far beyond our ability to use it for genuine human welfare. "War and preparation for war are standing temptations to make the present bad, God-eclipsing arrangements of society progressively worsen as technology becomes progressively more efficient" (Aldous Huxley, The Perennial Philosophy, p. 96). . These dark forces have created chaos in society.

War is an industry motivated by financially profitable motives.. The comments of two Nobel Laureates command our attention. In 1986, Professor Maurice H. Wilkins confirmed, "About half the world's scientists and engineers are now engaged in war industries." He warned, "I feel very strongly that most of the scientists are being led increasingly into a rather limited way of thinking, without much open-mindedness, working for material ends." Professor George Wald (1908-1998) was one of the first scientists to speak out in that forum against America's involvement in the Vietnam War. He said, "Killing has become a profitable business now" (cit. from Gazette, "Resident and Fellows of Harvard College 1998").

Einstein's directive to his followers is echoed by millions today:

You must warn people not to make intellect their God. The intellect knows methods but seldom knows values. They come from feeling. If one does not play his part in the creative whole, he is not worth being called human-he has betrayed his purpose. (Einstein and the Poet, p. 135)

Einstein constantly articulated his moral concerns to his students. He appealed to them to nurture that "holy curiosity" that would lead them to search for the ultimate truth and that would develop their character, making them sufficiently strong to embody the truth. He hoped to save them from the fundamental error committed by modern people who neglect or disobey the laws of spiritual development. Their idealization of the intellect as a master key that opens the secrets of nature arbitrarily reduces them to intellectual animals. Swami Vivekananda says:

It is one of the evils of civilization that we are after intellectual education alone and take no care of the heart. It only makes man ten times more selfish, and that will be our destruction. Intellect can never become inspired; only the heart when it is enlightened, becomes inspired. An intellectual, heartless man never becomes an inspired man ... Intellect has been cultured, with the result that hundred of sciences have been discovered, and their effect has been that the few have made slaves of the many-that is all the good that has been done.

Artificial wants have been created; and every poor man, whether he has money or not, desires to have those wants satisfied, and when he cannot, he struggles, and dies in the struggle. This is the result. The way to solve the problem of misery is not through the intellect but through the heart. If all this vast amount of effort had been spent in making men purer, gentler, more forbearing, this world would have a thousandfold more happiness than it has today. (C. W., I: 412-15 passim)

People are less likely to form bonds inspired by selfless love and moral values than by tacit membership to the inhuman mob mentality ruled by passions, prejudice, and violence. "We are becoming casual about brutality. We have made our peace with violence." Our mind is conditioned but not enlightened; endowed with intelligence we remain heartless, we call ourselves civilized but flaunt our lack of culture-"We know the price of everything but the value of nothing."

Einstein's vision of life is truly refreshing in our depressing times when science, the God of the age, has lost its glamour and prestige. We know instinctively that Einstein was not solely concerned with scientific truth. He was equally and perhaps more concerned with moral truths that develop human integrity. It was natural for him-to visualize an era of human happiness in which scientists seeking truth develop a comprehensive view of life. His solutions to scientific problems are linked to a profound philosophy. "Meeting him in old age was rather like being confronted by a second Isaiah-even though he retained traces of a rollicking, disrespectful common humanity and had given up wearing socks" (C. P. Snow). Like the great Rishis, Einstein would transport himself into the realm of deep mysticism that transcends parochialism and prejudice. He wrote, "The most beautiful emotion we can experience is the mystical. He, to whom this emotion is strange, is as good as dead. This oft-quoted passage speaks volumes about his cosmocentric mind. His idea of cosmic religion and his staunch pacifism, unfailing humanism, passionate love for democracy, great regard for moral tradition, and above all, dynamic humaneness and simplicity make their irresistible appeal to the multitude.

There have been many books written about Albert Einstein and several written by himself. But Albert Einstein, His Human Side by Swami Tathagatananda is especially valuable in that it emphasizes an aspect of Einstein that is spiritually uplifting. The world knows of Einstein's genius and his role in the scientific breakthroughs of the twentieth century. But it doesn't know much about the man beneath the hype.

From the very beginning of his book, Swami Tathagatananda makes clear Einstein's aim of getting in touch with the hidden workings of the universe through mathematics, great classical music, and for a time, organized religion. He used these paths to free himself from the "merely personal" as he put it, from the egoistic life of most human beings.

There was also his anti-militarism, which was a feature of his life from boyhood. He was subject to violence as a result of his Jewishness, and because of this, as well as his innate nature, he abhorred violence. A number of times Swami Tathagatananda mentions Einstein's veneration of Mahatma Gandhi who he thought was the only great political leader of the twentieth century. Einstein felt that only a world government could keep the peace on this earth.

He was a great believer in education that wasn't regimented, one that gave students the freedom to pursue their interests and figure things out for themselves. Education should train students to think, not cram their minds with facts. As Swami indicates, figuring out the laws of physics which describe the workings of the universe was one of Einstein's ways of rising above the humdrum and petty concerns of everyday life, a trite life to Einstein's thinking. As he said on one occasion, "The love of science lifts me impersonally from the vale of tears to the peaceful spheres," and on another, "Work is the only thing that gives substance to life." He also used his violin playing as another method of upliftment.

Over and over Swami comes back to Einstein's view that "only a life lived for others is a life worthwhile" and that "only morality in our actions can give beauty and dignity to life." All his life he showed himself to be very unselfish, hardly caring about the clothes on his back. He once said to his second wife's two daughters, "use for yourself little but give to others much." And along the same lines he said, "A hundred times every day I remind myself that my inner and outer life is based on the labors of other men, living and dead, and that I must exert myself in order to give in the same measure as I have received and am still receiving." Indifferent to praise and censure, he used his fame to help others and spread positive ideas in the world.

Like Gandhi, Einstein was always somewhat detached from even those closest to him. Perhaps this was because, like Gandhi, he was consumed by his cause-in this case to find out the secrets of the universe. Indeed, this pursuit of knowledge seemed to be Einstein's religion. And he said that the scientist's "religious feeling takes the form of a rapturous amazement at the harmony of natural law, which reveals an intelligence." Indeed, for him, the world's comprehensibility was a "miracle." Or as he put it elsewhere, " I have no better expression than 'religious' for this confidence in the rational nature of reality and in its being accessible to some degree to human reason." As Swami sums it up, "To Einstein, God was a metaphor for the transcendent Unity."

Success did not come easily for Einstein. As a young man he had considerable difficulty getting a job, and this became especially vexing after his father died and he needed to support his mother. One is reminded of Swami Vivekananda's plight after the death of his father, when it seemed no one was willing to hire him. None of Einstein's difficulties ever soured him on humanity. He once said, "I feel such solidarity with all living people that it is a matter of indifference to me where the individual begins and where he ceases.

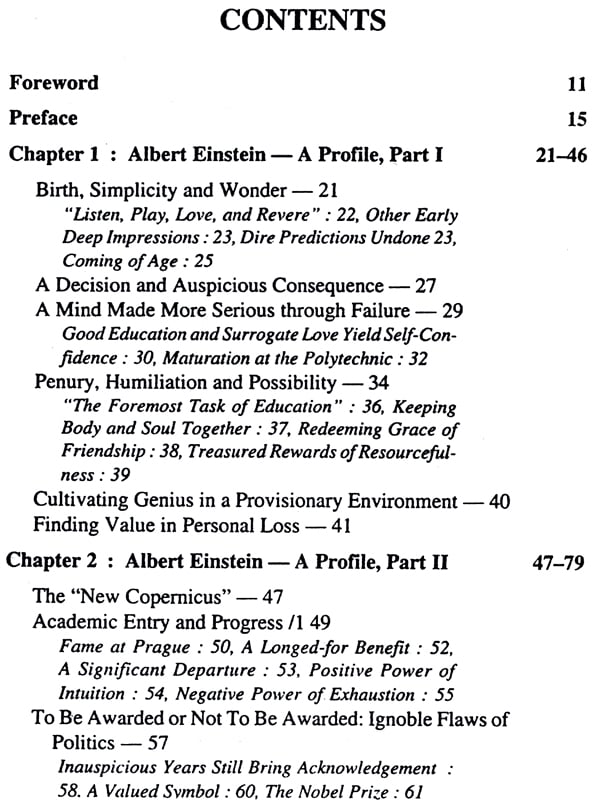

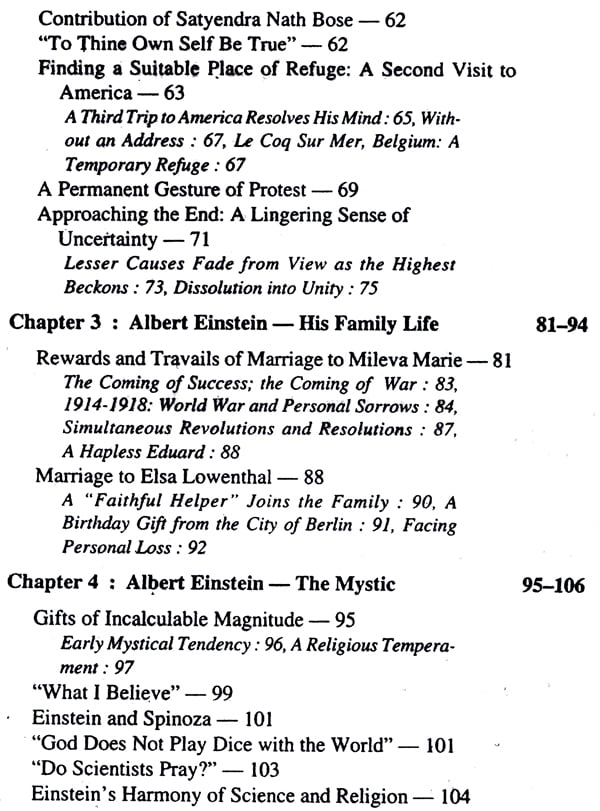

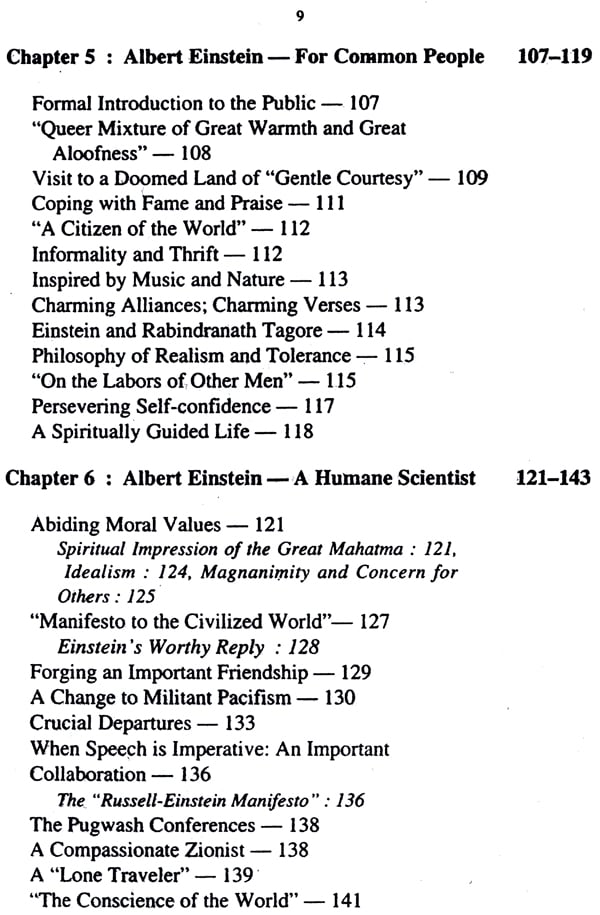

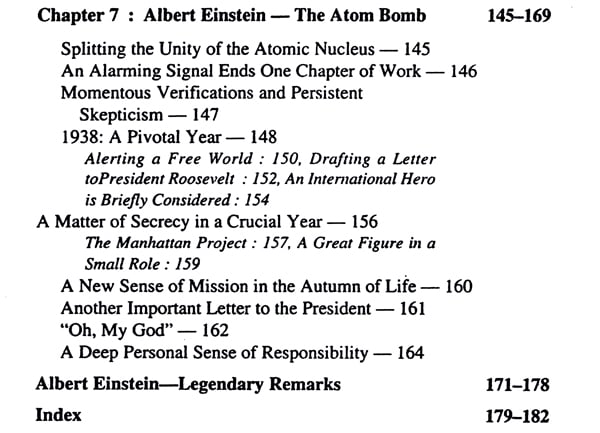

**Contents and Sample Pages**