Ancient Futures (Learning From Ladakh)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAF878 |

| Author: | Helena Norberg-Hodge |

| Publisher: | Oxford University Press, New Delhi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2021 |

| ISBN: | 9780195631968 |

| Pages: | 224 (Throughout Color and B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 230 gm |

Book Description

About the Book

While providing an intimate look at Ladakhs traditional culture, Ancient Futures raises important questions about the psychological, social, and environmental costs of modernization.

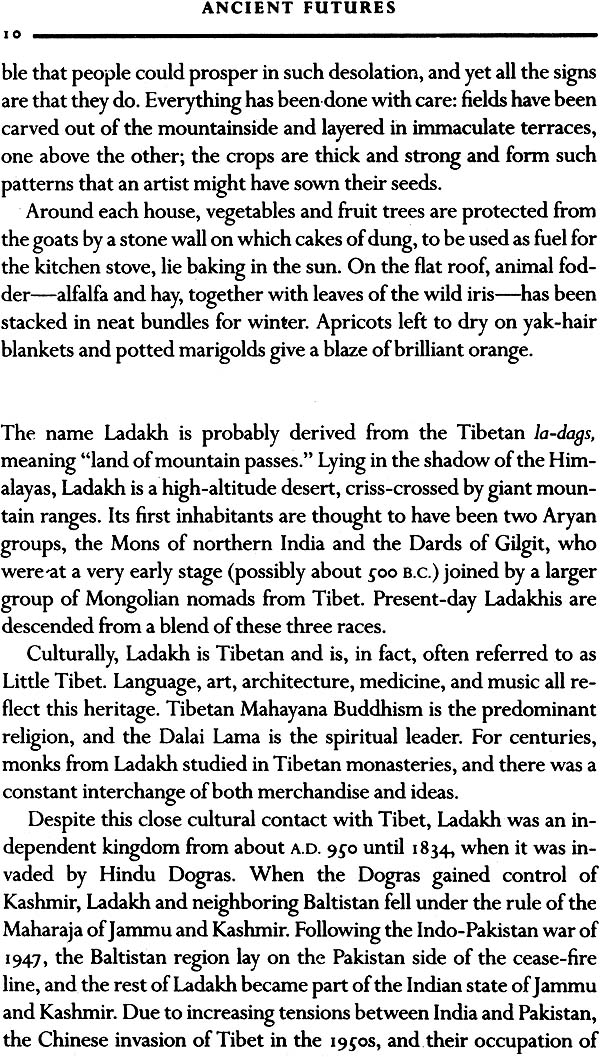

Ladakh or Little Tibet is a place of few resources and an extreme climate. Yet, for more than a thousand years, it has been home to a thriving culture. Traditions of frugality and cooperation, coupled with an intimate and locationspecific knowledge of the environment, enabled the Ladakhis not only to survive, but to prosper. Then modernization arrived, ostensibly as a means to progress and real prosperity. Now in the modern sector one finds pollution and divisiveness, intolerance and greed. Centuries of ecological balance and social harmony are under threat from the pressures of Western consumerism.

Part anthropology, part uncompromising critique, Ancient Futures has been made into an awardwinning film of the same title and translated into more than 30 languages.

About the Author

Helena NorbergHodge was one of first outsiders to visit Ladakh when it was opened to tourists in the mid1970s and the first Westerner in modern times to master the Ladakhi language. For her work as director of the Ladakh Project she was awarded the Right to Livelihood Award, also known as the Alternative Nobel Prize, in 1986. She is the founderdirector of the International Society for Ecology and Culture.

Preface

Helena NorbergHodge has long been a friend of Ladakh and its people. In this book she expresses her deep appreciation for the traditional Ladakhi way of life, as well as some concern for its future.

Like Tibet and the rest of the Himalayan region, Ladakh lived a selfcontained existence, largely undisturbed for centuries. Despite the rigorous climate and the harsh environment, the people are by and large happy and contented. This is no doubt due partly to the frugality that comes of selfreliance and partly to the predominantly Buddhist culture. The author is right to highlight the humane values of Ladakhi society, a deeprooted respect for each others fundamental human needs and an acceptance of the natural limitations of the environment. This kind of responsible attitude is something we can all admire and learn from.

The abrupt changes that have taken place in Ladakh in recent de cades are a reflection of a global trend. As our world grows smaller, previously isolated peoples are inevitably being brought into the greater human family. Naturally, adjustment takes time, in the course of which there is bound to be change.

I share the authors concern for the threatened ecology, of our planet and admire the work she has done in promoting alternative solutions to many of the problems of modern development. If the Ladakhis enduring treasure, their natural sense of responsibility for each other and their environment, can be maintained and reapplied to new situations, then I think we can be optimistic about Ladakhs future. There are young Ladakhis who have completed a moderneducation and are prepared to help their own people. At the same time traditional education has been strengthened in the monastic system through the restoration of links with Tibetan monasteries re established in exile. Finally, Ladakh has an abundance of sympathetic friends from abroad, who, like the author, are ready to offer support and encouragement.

No matter how attractive a traditional rural society may seem, its people cannot be denied the opportunity to enjoy the benefits of modern development. However, as this book suggests, development and learning should not take place in one direction only. Amongst the people of traditional societies such as Ladakhs there is often an inner development, a sense of warmheartedness and contentment, that we would all do well to emulate.

Introduction

Ladakh, under Karakoram, in the transHimalayan region of Kashmir, is a remote region of broad arid valleys set about with peaks that rise to 20,000 feet. It lies in the great rainshadow north of the Himalayan watershed, in a sere land of wind, high desert, and remorseless sun. It is easier to travel north into Tibet than south across the Himalayas to the subcontinent, and the people speak a dialect of the Tibetan tongue. Like Assam, Bhutan, the Mustang and Dolpo regions of northern Nepal, and other mountainous regions of the great Himalayan frontier, Ladakh for the past one thousand years has been an enclave of Tibetan Buddhism.

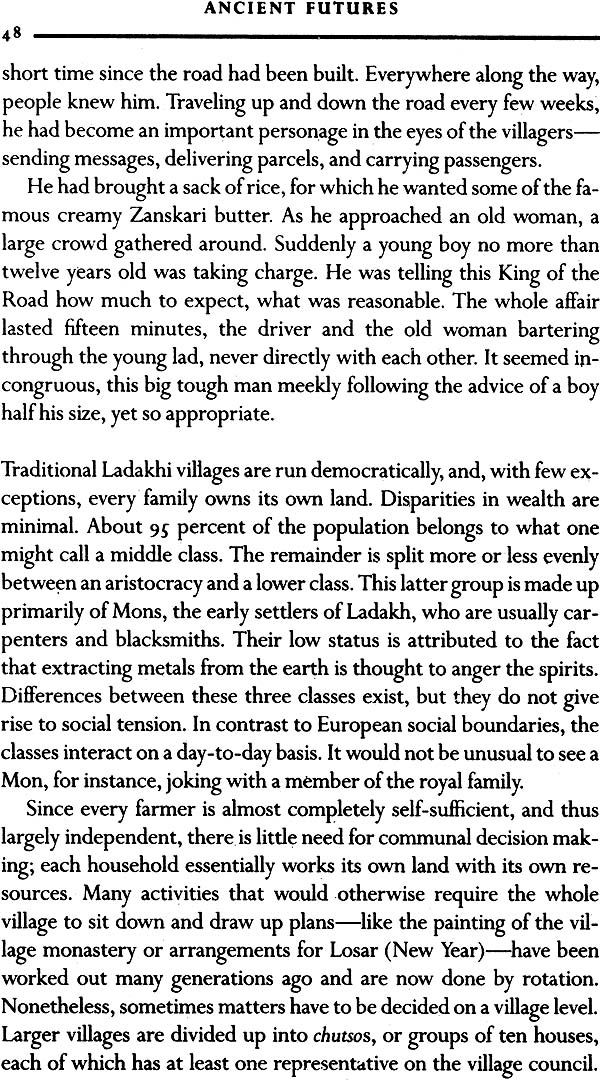

Politically, La da Bs, the Land, is a semiautonomous district divided (by the Britishadministered partition of (947) between Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India. Culturally, it is fat more ancient, a two thousandyearold kingdom of Tatar herders who have learned how to grow barley and a few other hardy cropspeas, turnips, potatoesin the brief growing season at these high altitudes. Black walnut trees and apricots are maintained at the lower elevations. The doughty way of Ladakhi life is made possible by skillful use of the thin soil and scarce water, and by hardy domestic animalssheep, goats, a few donkeys and small shaggy horses, and in particular the dzo, a governable hybrid of archaic Asian cattle with the cantankerous semiwild black ox known as the yak. These animals furnish a resourceful folk with meat and milk, butter and cheese, draft labor and transport, wool, and fuel. In a treeless land, the dried dung cakes of the cattle, gathered all year, are a precious resource, supplying not only cooking fuel but meager heat in the long winters in which temperatures may fall to 40 F.

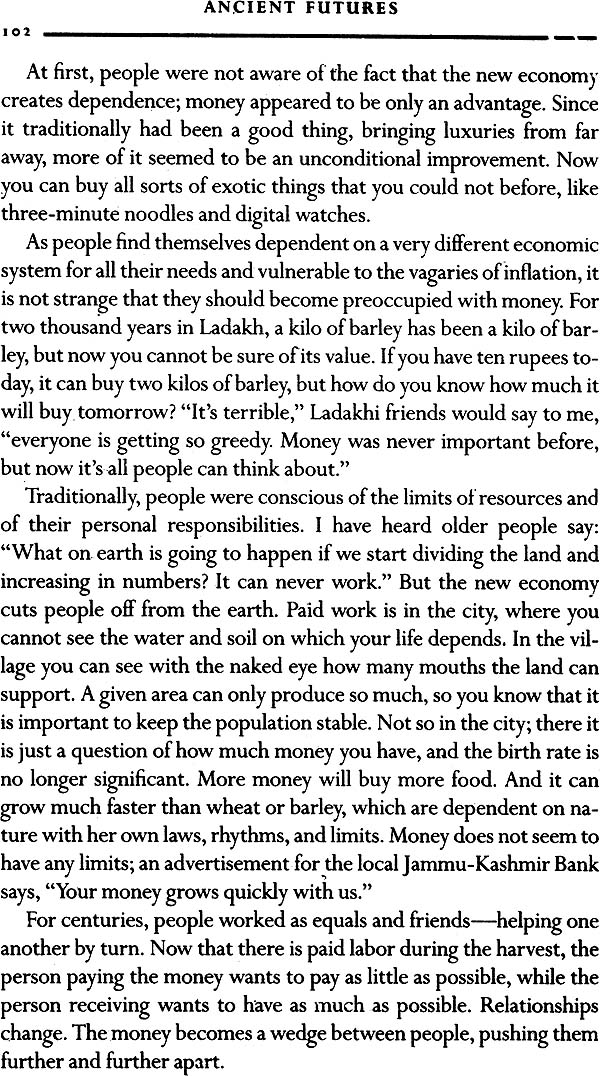

Until recent years, essential needs of the Ladakhishousing, clothes, and foodwere produced locally, by hand, and so a precious resource is communal labor, which is given generously for house construction (stones and mud, whitewashed with lime) or in harvest season, or for tending herds. The high altitudes are greener than the valley floor, and the herds, taken to high pastures in the summer, are thereby kept away from the small barley fields and vegetable gardens. Livestock manure is gathered for cooking fuel and winter heating, and human waste, mixed with ash and earth, is spread upon the gardens; there is no pollution. Thus nothing is wasted and nothing thrown away; a use is found for everything.

In the very grain of Ladakhi life are the Buddhist teachings, which decry waste, and encourage the efficient husbanding of land and watera frugality, as Helena NorbergHodge points out, that has nothing to do with stinginess (also decried in Buddhist teachings) but arises, rather, from respect and gratitude for the limited resources of the land. Water is drawn carefully from glacial brooksone stream may be reserved for drinking, the next for washing. Indeed, it is painstaking attention to each object: and each moment that makes possible this selfsustaining culture that nonetheless provides Ladakhis with much leisure time.

Watching a mother and her two daughters watering, I saw them open small channels and, when the around was saturated, block them with a spadeful of earth. They managed to spread the water remarkably evenly, knowing just where it would flow easily and where it would need encouragement. A spadiful dun out here, put back there; a rock shifted just enough to open a channel. All this with the most delicate sense of timing. From time to time they would lean on their spades and chat with their neighbors, with one eye on the waters progress.

Like the Hopi and other Amer Indian peoples (now thought to have come from the same regions near Lake Baikal and the Gobi Desert as the Tatar peoples who came later to this Himalayan region), the Ladakhis share the Tibetan perception of a circular reality, with life and death as two aspects of an everreturning process, and even in certain details of material culture, comparisons with AmerIndian ways are very interesting. The barley farina known in Ladakh as ngamphe is called tsampa in Tibetan; a very similar corn farina made in America by Algonkian peoples is called samp.

Even if samplsampa were mere coincidence, other parallels are not easily dismissed, such as the custom that a habitation should face east toward the sunrise, the prohibition against telling tales in winter, certain healing techniques mysterious to Westerners, and the profound respect for old people and children, who are welcomed to each activity of every day. In Amerindian tribes of the Amazonian basin, one may be banished into the surrounding forest for displaying anger; schon chan (one who angers easily) is one of the worst insults in the Ladakhi language. Rather than fume when put upon, as Westerners might do, the Ladakhi says, Chi choenWhats the point? Lack of pride is a virtue, for pride, born of ego, has nothing to do with self respect among these Buddhist people; I witnessed this repeatedly in Himalayan travels with Sherpas (in Tibetan, easterners) and the folk of Dolpo, who like the Ladakhis live a pure Tibetan Buddhist culture.

Though I have never found the opportunity to travel to Ladakh since the author first invited me ten years ago, the aesthetic and spiritual correspondences between this land and Dolpo are very obvious in her account. Both are dry, fierce, all but treeless mountain landscapes set about with stupas and chortens, prayer flags and cairns, and prayer walls of carved stones. The dominant wild animals are the blue sheep (actually a goat), Asian wolf, and snow leopard. The author describes the experience of a Ladakhi shepherdess tending her sheep along a ravine:

Just above the path, a ball of burtse, a shrub that is used as fuel, began rolling down the scree: not bouncing, as you would expect, but olidino smoothly, even over bumpy stones. It surprised her; she had never seen anything like this before. Puzzled, she watched it roll closer. As it came to a standstill a Jew yards from the animals, it looked up at her, this shrub, and she suddenly realized what it wasa snow leopard.

The celebration here of traditional Ladakhi life induces exhilaration but also sadness, as if some halfremembered paradise known in an other life had now been lost. So evocative is it that I feltIm not sure whathomesickness for the Crystal Monastery? Or perhaps a memory of home going, as if I were returning to lost paradise, that ancient and harmonious way of life that even Westerners once knewand indeed still knowin the farthest corners of old Europe.

The Ladakhis attitude to lifeand deathseems to be based on an intuitive understanding if impermanence and a consequent lack if attachment. Rather than clinging to an idea if how things should be, they seem blessed with an ability to actively welcome things as they are .

It is easy to romanticize selfsufficient economies and traditional technologies, and it is also easy, as the author makes clear, to ignore their benefits, from the consolations of working the soil with draft animals rather than tractors to grinding grain with waterpowered wheels instead of engines. Many archaic societies are more sustain able than our own in terms of their relationship with the earth, and their patterns of living more conducive to psychological balance more in touch, as the author says, with our own human nature, showing us that peace and joy can be a way of life, Anyone with experience of such societies can testify that this thinking is neither wishful nor romantic. Anyway, Ms. NorbergHodge is essentially pragmatic and hardheaded:

[The] onedimensional view of progress, widely favored by economists and development experts, has helped to mask the negative impact of economic growth. This has led to a grave misunderstanding of the situation of the majority of people on earth todaythe millions in the rural sector of the Third Worldand has disguised the fact that development programs, far from benefiting these people, have, in many cases, served only to lower their standard of living.

Modern technologies, based on capital and fossil fuels, lead inevitably to centralization and specialization, to cash crops as opposed to subsistence agriculture and barter, to timewasting travel and stressful town life among strangers. And they are laborsaving only in the narrowest sense, since gaining ones livelihood in the new ways, which are competitive rather than communal, demands more time. Dependence on international trade for goods and materials leads in evitably to a monoculturethe same sources and resources for both material and abstract needs, from dress to musicand, increasingly, a common language (a pauperized English, in most cases), and even a common education and set of values, with corresponding dismissal and even contempt for the local culture. Modern education tends to belittle local resources, teaching children to find inferior not only their traditional culture but themselves.

Meanwhile, the intense competition that replaces barter and communal effort leads inevitably to increasing dissatisfaction, greed, dispute, and even war, all on behalf of an economic model that the lo cal people cannot emulate and that, even if they could, would almost certainly be inappropriate for Ladakh (and other Third World lands of narrow resources). Yet the future of such countries lies entirely in the hands of development corporations and financial institutions, including the World Bank, where decisions are based on Western economic systems rather than the welfare of the client states.

Another unfortunate consequence of disruption is population in crease, which underlies the breakdown of cultures the world over. Until recent years, the Ladakhi population was well adjusted to the limited amount of arable land and the slender resources of water and stock forage. The increasing dependence on the outside world, the author says, erodes personal responsibility and clouds the fact that resources are limited. Optimists assume that we will be able to invent our way. out of any resource shortage, that science will somehow stretch the earths bounty ad infinitum. Such a view is a denial of the fact that there are limits in the natural world which are beyond our power to change, and conveniently circumvents the need for a redistribution of wealth. A change in the global economy is not necessary if you believe that there is going to be more and more to go around.

Is it (as suggested here) that the wouldbe corporate developers and the wouldbe benefactors, with their inappropriate technologies, are out of touch with reality, or is it that, while quite awarein deed, more aware than anybody elseof the debt, dependence, and environmental pollution being inflicted on a formerly clean and self reliant culture, they pure nonetheless the easy shortterm profit, leaving behind not just pollution but frustration, misery, and anger? For the ethical basis of traditional Buddhist belief, based on the unity and mutual interdependence of all life, is grievously missing from the Western codes that now impinge upon the people of Ladakh.

The Buddhist ability to adjust to any situation, to feel happy regardless of circumstances, is already eroded, and so is that deep rooted contentedness that they took for granted. Only sixteen years ago, when Helena NorbergHodge first went to Ladakh, the people would not sell their old wood butter jars no matter what was offered by their few visitors; today, only too eager to sell, they store their butter in tin cans.

From a social point of view, the losses that accrue to misguided development may become even more painful than the material ones. As the author demonstrates, the small communities and large extended families of Ladakhi life are a better foundation for growing up than the unnatural alienation of leaving home, which leads, paradoxically, to clinging and grasping attitudes and relationships that directly contravene the Buddhist teachings. In addition to the contempt for ones own culture, the aspiration for what one is taught to want but will never (in the great majority of cases) have is encouraged by misplaced technological progress and its many ills. With the advent of specialization, work is done away from home, social life depends on business associates and strangers, and the children are increasingly excluded. The culture fragments at an everincreasing rate, as socalled progress divides the Ladakhis from their native earth, from one another, and from what Buddhists call their own true nature.

As Wendell Berry has written in The Unsealing if America:

What happens under the rule if specialization is that, thou8h society becomes more and more intricate, it has less and less structure. It becomes more and more organized, but less and less orderly. The community disintegrates because it loses the necessary understandin8s,jorms and enactments if the relations amon8 materials and processes, principles and actions, ideals and realities, past and present, present and future, men and women, body and spirit, city and country, civilization and wilderness, growth and decay, life and deathjust as the individual character loses the sense if a responsible involvement in these relationships.

The only possible 8uarantee if the future is responsible behavior in the present. When supposed future needs are used to justify misbehavior in the present, as is the tendency with us, then we are both pervercin8 the present and diminishing the future.

Although responsible use may be defined, advocated, and to some extent required by organizations, it cannot be implemented or enacted by them. It cannot be effectively enforced by them. The use if the world is finally a personal matter, and the world can be preserved in health only by the forbearance and care if a multitude if persons.

Helena NorbergHodge is certainly one of those persons, and her valuable book cries out to those who are not. On occasion over the years, I have attended her eloquent public appeals, and know how effective an advocate she is, not only because of her intelligence and sincerity and presence but because of a profound commitment that has taken her to Ladakh for half the year for the past sixteen years.

A highly trained linguist who had studied in five countries and spoke six languages, she learned the Ladakhi dialect in her first year, and since then she has informed herself in all the societal, environ mental, and alternative energy disciplines that she had to understand in order to establish the remarkable Ladakh Project, set up to warn the Ladakhis of the longterm sideeffects of conventional development and to present practical alternatives, from the demonstration of solar heating systems to educational programs for schoolchildren. Since its founding, the Project has earned the strong enforcement of numerous world figures. Ancient Futures reveals a knowledge of certain complex principles of Buddhist doctrine that permit her to understand this ancient social order that much betterthe humanism of old ways that worked, emotionally as well as economically, now threatened with fatal loss by ways that dont.

This is not to say that the pervasive human wellbeing in Ladakh is gone forever. Indeed, it is one of the virtues of this book that it points to real solutions, and ends on an inspiring note of hope and determination. As. the author suggests, we have much to learn from Ladakhi culture, and we will ignore these teachings at our peril.

Prologue

LEARNING FROM LADAKH

Why is the world teetering from one crisis to another? Has it always been like this? Were things worse in the past? Or better?

Experiences over more than sixteen years in Ladakh, an ancient culture on the Tibetan Plateau, have dramatically changed my response to these questions. I have come to see my own industrial culture in a very different light.

Before I went to Ladakh, I used to assume that the direction of progress was somehow inevitable, not to be questioned. As a con sequence, I passively accepted a new road through the middle of the park, a steelandglass bank where the twohundred year old church had stood, a supermarket instead of the corner shop, and the fact that life seemed to get harder and faster with each day. I do not any more. Ladakh has convinced me that there is more than one path into the future and given me tremendous strength and hope.

In Ladakh I have had the privilege to experience another, saner way of life and to see my own culture from the outside. I have lived in a society based on fundamentally different principles and witnessed the impact of the modern world on that culture. When I arrived as one of the first outsiders in several decades, Ladakh was still essentially unaffected by the West. But change came swiftly. The collision

between the two cultures has been particularly dramatic, providing stark and vivid comparisons. I have learned something about the psychology, values, and social and technological structures that support our industrialized society and about those that support an ancient, naturebased society. It has been a rare opportunity to compare our socioeconomic system with another, more fundamental, pattern of existencea pattern based on a coevolution between human beings and the earth.

Through Ladakh I came to realize that my passivity in the face of destructive change was, at least in part, due to the fact that I had confused culture with nature. I had not realized that many of the negative trends I saw were the result of my own industrial culture, rather than of some natural, evolutionary force beyond our control. With out really thinking about it, I also assumed that human beings were essentially selfish, struggling to compete and survive, and that more cooperative societies were nothing more than utopian dreams.

It was not strange that I thought the way I did. Even though I had lived in many different countries, they had all been industrial cultures. My travels in less developed parts of the world, though fairly extensive, had not been enough to afford me an inside view. Some in tellec.ual travels, like reading Aldous Huxley and Erich Fromm, had opened a few doors, but I was essentially a product of industrial society, educated with the sort of blinders that every culture employs in order to perpetuate itself. My values, my understanding of history, my thought patterns all reflected the world view of homo industrials.

Mainstream Western thinkers from Adam Smith to Freud and to days academics tend to universalize what is in fact Western or industrial experience. Explicitly or implicitly; they assume that the traits they describe are a manifestation of human nature, rather than a product of industrial culture. This tendency to generalize from Western experience becomes almost inevitable as Western culture reaches out from Europe and North America to influence all the earths people.

Every society tends to place itself at the center of the universe and to view other cultures through its own colored lenses. What distinguishes Western culture is that it has grown so widespread and so powerful that it has lost a perspective on itself; there is no other with which to compare itself. It is assumed that everyone either is like us or wants to be. Most Westerners have come to believe that ignorance, disease, and constant drudgery were the lot of preindustrial societies, and the poverty, disease, and starvation we see in the developing world might at first sight seem to substantiate this assumption. The fact is, however, that many, if not most of the problems in the Third World today are to a great extent the consequences of colonialism and misguided development.

Over the last decades, diverse cultures from Alaska to Australia have been overrun by the industrial monoculture. Todays conquistadors are development, advertising, the media, and tourism. Across the world, Dallas beams into peoples homes and pinstripe suits are de rigueur. This year I have seen almost identical toy shops appear in Ladakh and in a remote mountain village of Spain. They both sell the same blonde, blueeyed Barbie dolls and Rambos with machine guns.

The spread of the industrial monoculture is a tragedy of many dimensions. With the destruction of each culture, we are erasing centuries of accumulated knowledge, and as diverse ethnic groups feel their identity threatened, conflict and social breakdown almost inevitably follow.

Increasingly, Western culture is coming to be seen as the normal way, the only way. And as more and more people around the world become competitive, greedy, and egotistical, these traits tend to be attributed to human nature. Despite persistent voices to the contrary, the dominant thinking in Western society has long assumed that we are indeed aggressive by nature, locked in a perpetual Darwinian struggle. The implications of this view for the way we structure our society are of fundamental importance. Our assumptions about human nature, whether we believe in inherent good or evil, underlie our political ideologies and thus help to shape the institutions that govern our lives.

Contents

| Preface by H. H. The Dalai Lama | ix | |

| Introduction by Peter Matthiessen | xi | |

| Prologue: Learning from Ladakh | 1 | |

| PART ONE: TRADITION | ||

| 1 | Little Tibet | 9 |

| 2 | Living with the Land | 19 |

| 3 | Doctors and Shamans | 37 |

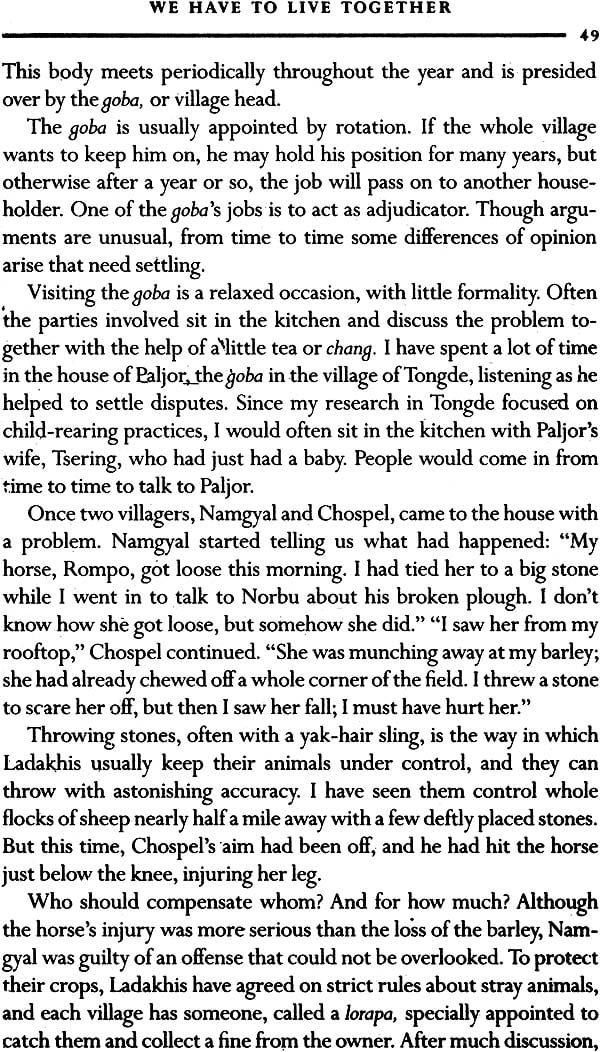

| 4 | We Have to Live Together | 45 |

| 5 | An Unchoreographed Dance | 55 |

| 6 | BuddhismA Way of Life | 72 |

| 7 | Joie de Vivre | 83 |

| PART TWO: CHANGE | ||

| 8 | The Coming of the West | 91 |

| 9 | People from Mars | 94 |

| 10 | Money Makes the World Go Round | 101 |

| 11 | From Lama to Engineer | 105 |

| 12 | Learning the Western Way | 110 |

| 13 | A Pull to the Center | 115 |

| 14 | A People Divided | 122 |

| PART THREE: LOOKING AHEAD | ||

| 15 | Nothing Is Black, Nothing Is White | 133 |

| 16 | The Development Hoax | 141 |

| 17 | CounterDevelopment | 157 |

| 18 | The Ladakh Project | 171 |

| Epilogue: Ancient Futures | 180 | |

| Readina List | 193 | |

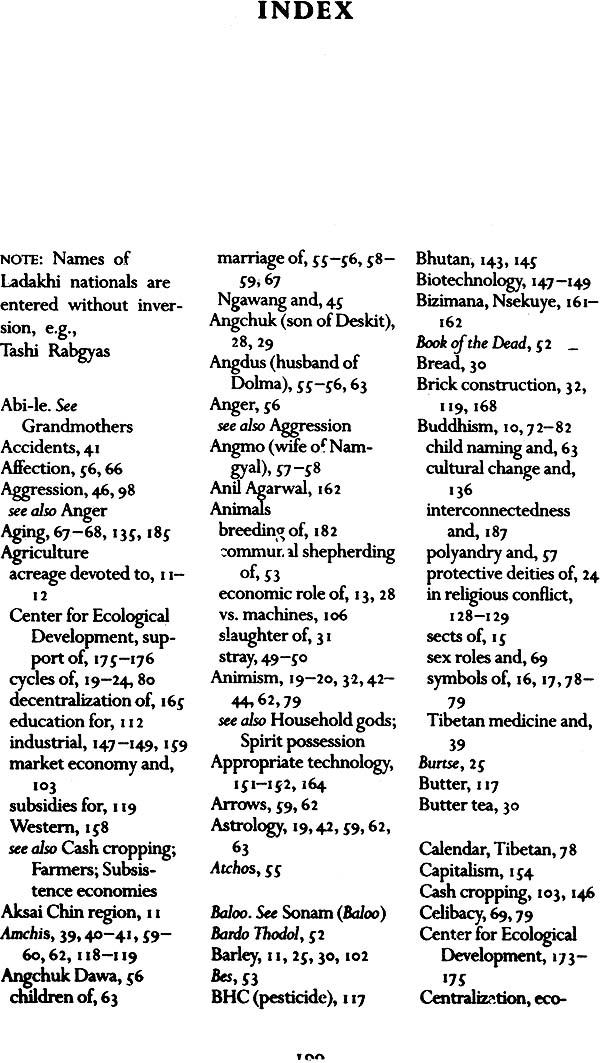

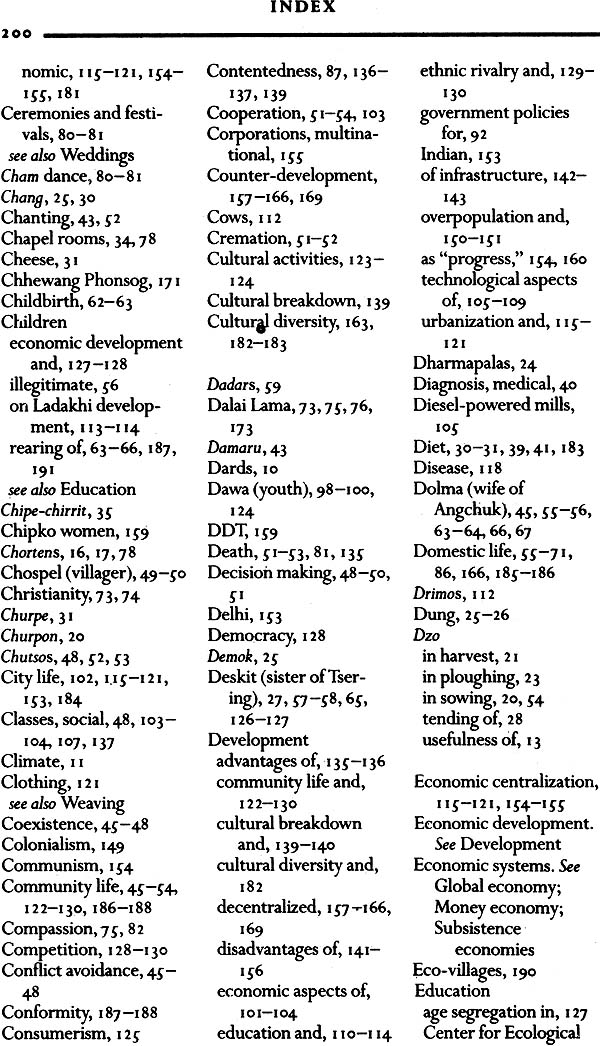

| Index | 199 |