Breaking Boundaries with The Goddess (New Directions in the Study of Saktism)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAF227 |

| Author: | Cynthia Ann Humes and Rachel Fell McDermott |

| Publisher: | Manohar Publishers and Distributors |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2009 |

| ISBN: | 9788173047602 |

| Pages: | 420 (Throughout Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.0 inch x 6.0 inch |

| Weight | 690 gm |

Book Description

Breaking boundaries with the Goddess draws together twelve Sakta interpreters from North America. Europe and India to discuss the present state and future challenges of Studies of the south Assian Goddess. They focus on Sanskrit, Tamil, Bengali, and tribal languages, and they cover geographic areas from the north to the south of the subcontinent and beyond, including Tibet and even parts of central Asia that were once under Kusana rule.

Their sources are wide ranging: they investigate archaeological finds from the Indus valley, sculptures recovered in robbers hordes in eastern India and sites excavated by the Russians near Afghanistan. They read texts, including Vedas, Agamas, epics, Puranas, Tantras, medieval ritual digests, and glorifications; examine rituals, art, and social attitudes; and their fieldwork takes them to meet tribal khonds, Gonds, Oraons, and Nagas, Bengali Tantric practitioners and temple priests and devotees. Numerous goddesses find their way into the pages of this volume; the vedic viraj, Laxsmi, Sita, Durga Mahisamardini, Kali, Korravali, tribal goddesses such as Tari Penu and Anna Kuari, the ten Mahavidyas, Jagaddhatri , various Yaksinis Vindhyavasini, and even goddesses whose names cannot be deciphered with our present knowledge. All of the contributors write in honor of the late professor Narendra Nath Bhattacharyya (1934-2001), the Bengali master interpreter of Saktism who mentored many of them and influenced the field tremendously with his insistence that the study of ritual or text not be divorced from a consideration of social institutions particularly those derived from tribal culture and his belief that the importance of women as ritual actors purveyors of tradition not be forgotten.

Cynthia Ann Humes is Chief Technology of Religious Studies at Claremont McKenna College. In addition to north Indian goddess worship, her research today focuses on the Phenomenon of the guru and western meditative practices.

Rachel Fell McDermott is Associate professor and chair, Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Cultures, Barnard College, Columbia University. Her Publications center on devotional and ritual traditions to Kali, Durga, and Uma in Bengal.

This book was intended to be a felicitation volume; sadly it has become a commemoration. The fault for this lies mostly with us the editors, who took an inordinate amount of time to collect edit, and prepare the essays for publication; Kala or Time is responsible for the rest taking Naren-da away from us too early. The contributors to this volume represent only a fraction of the many scholars whom Nare-da touched professionally and personally during his academic life; he had a large network of colleagues at the University of Calcutta where he taught from 1966 to 1999 at Rabindra Bharati University where he worked as Visiting fellow at school of Vedic studies from 1992; at the various museums and art institutes in Calcutta; in the colleges and schools in his native Hooghly district; and at institutions of higher learning across India where he lectured and mentored promising scholars. Those of us assembled here many of us Westerners whom Nared-da aided in our research; other Indian colleagues with whom he worked closely in our own ways feel that our lives have been changed because of his kindness and example and that the course of our present and future research has been set in a fruitful direction because of his comments suggestions and scholarly publications.

Narendra Nath Bhattacharyya was a man of prodigious output mental flexibility and personal humility. Of his many published Bengali and English books seven were revised and update with the author publicly acknowledging that he had changed his ideas in light of new research or new theoretical approaches to old material. He was preparing manuscripts nearly until the day he died.

Bhattacharyya always loved the study of history. He received a BA in the subject from Hooghly colleges and was in the middle of an MA program in Modern History at the university of Calcutta when he suddenly withdrew to join Motilal Roy the founder of Prabartak sangha a constructivist society that worked for the uplift of the Poor in chandannagar. Whatever you want to do you should now your own culture Roy apparently told Bhattacharyya. Under the influence of Roy and another member of the society Nalin Chandra Datta Bhattacharya became interested in Indology and later in 1958 he obtained his MA in ancient Indian History and culture from the university of Calcutta. In 1964 he was awarded the Griffith memorial Prize for his easy. Indian puberty rites (published in 1968); and in 1965 he revived his PhD also from the same department at the university of Calcutta. His dissertation written under the supervision of the renowned historian D.C. Sircar was published in 1970 as the Indian mother Goddess. Once set upon this trajectory of interest and output Bhattacharyya travelled ahead with purpose and speed: by the time of his death in 2001 he had published thirty seven books twelve in Bengali and twenty five in English in addition to forty seven articles in English alone. Four additional English book manuscripts were on his desk at the time of his death and are to be published posthumously.

Several intellectual themes and commitments run like strong threads through his various literary creations. Perhaps the most important that which ties all of the rest together is his insistence that one attend to the social embeddedness of religious rituals and beliefs; in all my work which are mainly concerned with the religious history of India, I have always tried to assert that the study of any ritual or cult in itself is of no value unless it is used has a means to understand the vast and enormously complicated problems of Indian social history It was in fact this introduction of anthropological resources in addition to texts the traditional stock in trade of ancient Indian historians that won him the Griffith memorial prize for Indian puberty rites as he claimed in the published preface to that work the precise nature of the social institutions of ancient Indian is a question which the literary evidence is in itself too fragmentary to solve; The new data on book were account of surviving tribal and popular customs and institutions. For instance in Ancient Indian rituals and their social contents a survey of the conceptual and historical development of rituals associated with kingship initiation and puberty menstruation fertility and death and resurrection he argued that the investigation of contemporary Indian tribal societies could demonstrate how the earliest forms of Indian rituals probably derived from a tribal milieu before class and kingship were imposed upon the. Again in the Indian mother goddess he made claims about the linkages between early agriculture rites and beliefs connected with fertility goddesses clams he based on several types of nontextual evidence: in addition to coins and inscriptions information on the practices of modern tribal agriculturists and reports of women rites and customs. He plumbed mythic account of goods and demons from the more than three hundred tribes in the Indian subcontinent as source material for his book on Indian demonology. Overall these methodological principles of refusing to admit a great difference between tribal and modern forms of religion and trying to honor tribal culture rather than labelling it mere superstition or magic are eloquently stated in his book. Religions culture of North Eastern India: Human psychology is one and the same everywhere whether in Aryavarta or in Nagaland or in west Asia.

Integral to Bhattacharyya interest in uncovering submerged meanings in championing the cause of repressed peoples or elements in history is his critique of hierarchy and privilege. He detected behind the development of ideas in India evidence for the loss of tribal democracy and autonomy suppression of a women centred culture and the concomitant self elevation of a patriarchal kingly and priestly ethos in society. In fact the entire Indian way of life was for Bhattacharyya essentially the affair of the dominant class the higher castes which has nothing to do with the greater section of the people. Many of his books contains examples of this interpretive lens. How for instance did the agricultural goddess Durga get transformed into a war goddess? Maybe he speculated in The Indian Mother Goddess she represented the feelings of the peasants who had to contend with oppressive landlords and ruling classes and who caricatured their overlords as demons. In his later years he even counselled visiting scholars to stay away from Calcutta during the Durga Puja Season as the festival had been so commercialized and corrupted by priestly interests. Again in surmising about the original and sophisticated forms of the Vedic sacrifices or Yajnas he suggested that while they had their genesis in primitive magical beliefs and practices (they probably got) ensnared by the logic of pure society and [finally culminated in] a meaningless but profitable affair of the priests kept shrouded in deep mytery and jealously guarded. Finally he dedicated his first book on the Jains to the holy name of Lord Mahavira who inspired men to fight against oppression and exploitation disease and death cruelty and caste anger and pride deceit and greed. It was partly because of this theory of history that he evinced such a destruct of the Brahmanical textual tradition.

As is evident from these intellectual convictions, Bhattacharyya was a keen student of classical Marxism and fond of its idealistic and deterministic aspects. However he had an uneasy relation with Bengali communism and claimed at the end of his life that he bore a hatred for Indian communists because of their antinational activities and their denunciation of Indian culture. In this he was a follower of M.N. Roy, who was critical of Marxism for what he perceived to be its total disregard of the individual. In the 1990s, when he was revising several of his successful books for new editions Bhattacharyya toned down the Marxist flavor of his interpretations; in the preface to the second edition of his Jain Philosophy for example he observed that to stigmatize the Brahmanas as social and intellectual villains was unhistorical and prejudiced.

Aside from his socially conscious approach to intellectual history Bhattacharyya was faithful t several other methodological commitments as well three of which we wish to mention here the first was his open accepting and even forgiving attitude toward western scholarship. Although he chose not to wire in an overtly postcolonial fashion he was well aware of the failings of orientalise scholarship and cited the arrogance of imperialist interpreters in several of his books, English and Bengali. The western Indologists and their Indian counterparts undoubtedly rendered commendable service by editing translating and interpreting the ancient religious texts as a result of which new horizons have been opened in the field of religious studies. But at the same time one should admit that notwithstanding their sincere attempts their vision was circumscribed by the outlook they inherited from their own culture and traditions. In most cases they interpreted the Indian religious philosophical terms in close dependence on those of the West. But it will be wrong to say that they were indifferent to such problems.... Still in many cases some kind of superficial rendering could not be avoided and it is not possible even now. Indeed one could characterize the whole of Bhattacharyya academic career as an attempt to undermine the impact of western education (that) has made everyone so accustomed to western terms and concepts that it has now almost become impossible to stand squarely on pure Indian tradition. His Bengali writings in particular are aimed at acquainting students with Indian history his book on the Indian freedom movement (Bharater savadhinata Samgramer Itihas) is still regarded as authoritative and it has been reprinted many times. Furthermore because he was regarded as a historical authority on Hooghly district and chinsurah town where he lived all his life, he was entrusted by the state government ministry of Information Antiquities of the Hooghly District. Conversant with world history Bhattacharyya nevertheless defended that local.

In spite of his incisive critiques of western bias he was extremely appreciative of many western thinkers his books are full of references to western anthropologists sociologists and historians of religion and those of us from Europe or America who came into contact with him were all touched by his gentle humane and helpful attitude toward our research projects. One might in fact aver that it was his Marxist tendency to place people’s ideas in their socially deterministic environments that gave him the grace to be able forgive western Orientalism: as for those o us witting and researching at present Bhattacharyya cautioned against an overzealous unselfconscious and totalizing hermeneutic.

Another of Bhattacharyya methodological concern was the erasure of inappropriate academic boundaries. For him the study of ancient Indian necessitated a facility in the full range of religious and philosophical trends, which included the Buddhists and the Jains who he felt had much in common with those who came to be called Hindus. Buddhist and Jain materials are woven into many of this thematic books. The Indian mother goddess (1970, 1977, 1999) A Glossary of Indian (1991), Religious culture of North eastern India (1995) Indian Religions Historiography vol. I Mythology (2001) and he devoted a total of seven English books to one or the other tradition: Jain Philosophy : historical outline (1976, 1999) History of Indian ideas (1993) Jainism and Prakrit in Ancient and medieval India: Essays for Prof Jagdish Chandra Jain (1994) Tantric Buddhism Centennial Tribute to Dr. Benoytosh Bhattacharyya (1999) Tantrabhidhana : A Tantric Lexicon (2002) and Encyclopaedia of Jainism (forthcoming).

Pushing his scholarly frontiers even further, Bhattacharyya believed that insights derived from the comparative study of religion could be immensely beneficial in the historian interpretive task. During the 1960s he wrote serially in a Bengali weekly on reputed ancient and medieval texts covering Gilgamesh the Zend Avesta the Talmud ad Midrash, Greek, Latin and Chinese classics the Teutonic Edda European romances and chansons Indian religio-philosophical conceptions with those of the Greeks Babylonians Romans Egyptians, Arabs, Pesians, and Chinese. Something this served to indicate historical influences or similarity at other times it proved the distinctiveness of the Indian data. An example of the latter is his conclusion to a chapter devoted to the comparison of the Indian Mother Goddess and Advanced Religious streams Nowhere in the religious history of the world do we come across such completely female-oriented systems as Saktism.

This provides an appropriate transition to the ma

in thematic study of our book, Breaking Boundaries with the goddess. For we have chosen to emphasize one of Bhattacharyya favourite subjects one to which he returned again and again in his academic writings; the Goddess. He grew up in a mixed religious household with a sakta father and a Vaisnava mother but seemed to find the Goddess tradition more intellectually interesting. His formal passion for the topic derived from his college days when he read Frazer’s the golden Bough and Briffault The mother books that introduced him to the ideas of matriarchy and matrillineality magical fertility rites and beliefs leading to the development of the universal Mother Goddess cult. He found a compatible fit between the writings of these western goddess specialists most of whom were evolutionary anthropologists and the Marxist approach of his early intellectual guru Debiprasad Chattopadhyay.

His main work on Sakta history and religiosity History of the Sakta Religion (1974, 1996), the Indian Mother Goddess (1970, 1977, 1999) a chapter on Saktism in India Religious Historiography Vol. I (1996) and saktism and mother right in the sakti cult and Tara edited by D.C. sirear (1967) are chronological surveys of Sakta ideas cults rituals and social groups from prehistoric times to the modern period. His chief interpretive lens was the study of process and changes; he argued that primitive conceptions of fertility and regeneration emerged from the simple analogical association of earth and woman in terms of the magical principles of similarity and contiguity and then acquired new conceptual dimensions in subsequent ages. In its present form then saktism is essentially a medieval religion but it is a direct offshoot of the primitive mother goddess cult which was so prominent a feature of the religion of the agriculture peoples who based their social system on the principle of mother right. In this earlier works, Bhattacharyya agreed with Frazer regarding the theory of an ancient matriarchy in later or in new edition of earlier works he seemed more cautious. However he never ceased to idealize the early and to him purer strands of the Sakta tradition.

Closely linked with Saktism is Tantra another topic of perennial interest of Bhattacharyya and his readers. In his popular History of the Tantric Religions: A Historical, Ritualistic, and philosophical study (1982, 1999), in his characteristically wide-ranging manner, he covered a multitude of subjects: What he called Tantra’s primitive substratum, Tantric literature the question of influences (was the traditions indigenous to India?), the relationship between Buddhist and Hindu Tantra, Tantric practices sakta Tantra and Tantric Art Just as in his history of Indian Erotic Literature (1975), where he claimed that his goal was to sweep away the fog to exaggerated notions which have so long characterized the study of this subject so also in his study of Tantra. He wanted to encourage scholarship on a religious strand whose roots lay in a repressed vilified and often misunderstood part of the ancient Indian past: a society dominated by female-centered rites and sexual cults. In keeping with his Marxist scepticism however he was not himself persuaded by the Tantirkas whom he met during the course of his research. While he stoutly defended the contributions of Tantra to Indian ethical and liberative science he accorded no validity whatsoever to its ritualistic aspects. Indeed he had met many Tantrikas throughout his life but none of them convinced him that they were true adepts or powerful beings.

By the time of Bhattacharyya death he had proven that a man who had never travelled India, who never lived anywhere but the house in which he and his father had been born and who spent more than thirty years in an academic department without a private office a computer a fax machine a private phone or a funded research library could be an internationally recognized master interpreter and an encyclopaedic expert in the field of ancient Indian history. Those of us who have contributed essays to this volume do so with pride to be associated with his memory.

In Step With A Pioneer: Collegial Esteem And The Present Volume

Many of us work in fields defined or nuanced by the contributions of Narendra Nath Bhattacharyya. Part I of Breaking boundaries with the Goddess is devoted to research that re-examines familiar texts or familiar texts or familiar figures not only to further scholarly inquiry but also to tap hitherto unutilized resources. For example in Engendering alternative power Relation: The Viraj in the Vedic Tradition Kumkum Roy reaches back into Vedic texts for cosmogonic conception that might differ from the male myths of Purusa and Prajapati. What she finds is a minor tradition that is non-hierarchical and little touched by patriarchal values; the creative force of the Viraj. Although speculation focused on the Viraj eventually ceased to provide a viable alternative to the masculine Brahamanical norm the fact that it was accommodate and not obliterated in the late Vedic traditions signals to Roy the acknowledgment of its significance. Likewise, sanjukta Gupta surveys the long history of the Pancaratra Sri Vaisnava tradition examining pancaratra theological principles a pancaratra meditational icon of Sakti from the Kusana period and medieval debates about the ontological status of Lakshmi to show that philosophically ritually and theologically Sri or Lakshmi was far more important to the early tradition than she later became. Hence in once upon a time the supreme power: The theological rise and fall of lakshmi in Pancaratra scriptures Gupta demonstrates both what the past held and why it come under attack. A third example in this vein is the essay by Thomas B. Coburn sita fight which examines the Adbhuta Ramayana as a strong powerful deity who outstrips Rama in the demonslaying capacity killing not simply the ten headed Ravana but his thousand headed multiform. Coburn discusses the implications of this Sita the inverse of the demure and victimized heroine of Valmiki version and concludes that the Adbhuta Ramayana invites us both scholars and inhabitants of India to think about who Sita is in new ways.

Each of these three contributors shares with Bhattacharyya an interest in the past and a conviction about its relevance. Moreover Roy, Gupta and Coburn all argue that the diversity of Indian religio-philosophical strands is rarely suppressed; the viraj and the ultimately powerful Lakshmi and Sita are not erased but pressed down into subterranean layers of the tradition where they may when needed or rediscovered in particular historical situations rise to importance again. What further intrigued Bhattacharyya about these scholars essays when he heard about them before his death was their implicit recovery of a woman centric perspective. The Vedic tradition with its male priests male sacrificers and male creators and the Vaisnava communities focused on the dominant figures of Visnu and Rama may look patriarchal but gender neutral or gender equal features lie hidden within them waiting for notice.

A second set of essays grouped together in Part II under the heading Rethinking Blood cadavers and death presents new perspectives historical field oriented and textual on sacrifice. The three authors Francesco Brighenti June McDaniel and David Kinsley all consulted with Narendra Nath Bhattacharyya on the subjects of their research and he helped them either with their fieldwork or with their thinking or both.

Brighenti illumines the practice of animal sacrifice in the sakta tradition by looking back and around: first at what we can glean about sacrificial customs involving animals and perhaps humans in the ancient Indus culture; and then at ethnographic reports British and modern on continuing sacrificial practices among tribal societies in the Indian subcontinent. His traditions of Human sacrifice in Ancient and tribal India and their relations to Saktism perhaps more than any other essay in the present volume follows Bhattacharyya lead in attempting to construct a theory of evolution and development in which data from tribal and other non privileged groups are brought into the interpretive project for consideration. Also like agriculture fertility sacrifice and violence and links them to similar concepts prevalent in other of the world where religiously interpreted sacrifice is valued.

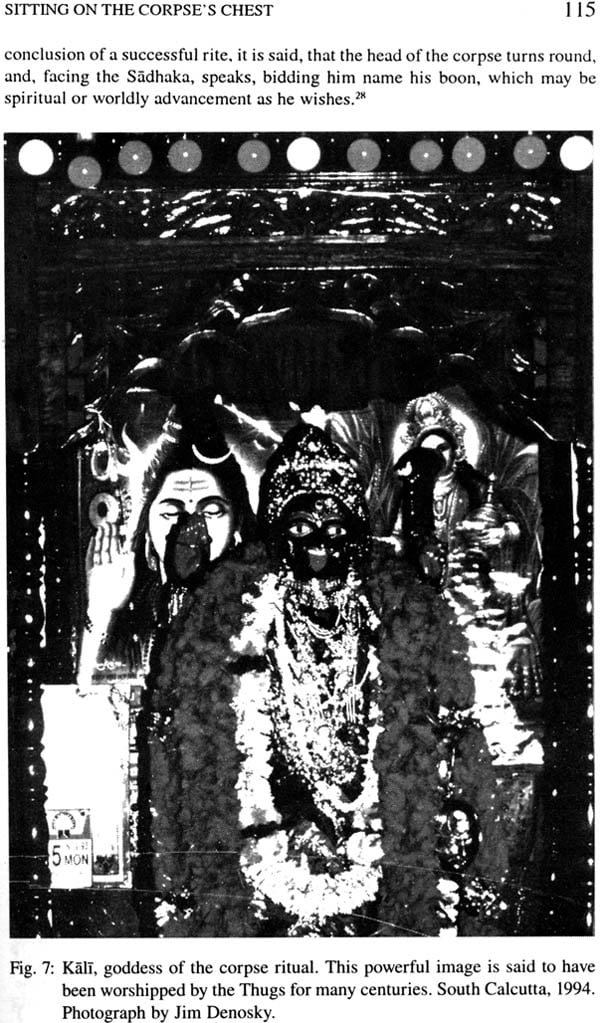

June McDaniel essay Sitting on the Corpse chest: The Tantric Ritual of Sava Sadhana and its variations in modern Bengali focuses on living Tantrikas in West Bengal whom McDaniel interviewed in the 1980s and 1990s. She describes contemporary Tantric attitudes toward and practices involving corpse rituals commenting that these can be categorized according to shamanistic yogic and devotional viewpoints. In addition she situates the practitioners and their rituals in the current communist political environment in west Bengal and defends her Tantric informants from charges of immorality. In this last sense although she is more sympathetic than Bhattacharyya to actual living Tantrikas she shares with him a dedication to the recovery, elucidation and vindication of an important but often maligned strand of the Indian religious tradition. The same is true from a more theological and psychological perspective of David R. Kinsley who in his Corpses severed heads and sex; reflections on the Dasamahavidyas attempts to understand what it is that is transformative and wisdom producing about the ten goddesses of great wisdom. In this essay originally written as the prototype for his alter book on the subject Tantric visions of the Divine Feminine; the ten mahavidyas Kinsley proposes a theological perspective from which the emphasis on decapitation blood and sacrifice in the worship of the ten Mahavidyas is liberating for the spiritual aspirant whether committed Tantric or devotional householder.

From texts and sacrifice we turn in Part III to art history. Both Bratindra Nath Mukherjee and Gautam sengupta start with a goddess images whose name provenance and context thy essay to identify. Mukerhjee is a wall painting in central Asia in western Tadzhikistan in a town called Pendzhikent seventy kilometres east of Samarkand whereas Sengupta is a black stone sculpture found in Raigunj in the district of North Dinajur in west Bengal. Despite their differing media and geographic locations both goddess depictions present their interpreters with similar difficulties; what tools can one use to identify them and how does one know when one has reached the limits of understanding? Mukerjee in the northernmost representation of an Indian goddess of power and Sengupta in An unnoticed form of Devi from Bengal and the Challenges of Art historical Analysis provide an instructive contrast in this regard. Both use common art historical techniques such as consulting texts comparing the image in question with other similar images from the region and examining historical and archaeological data to determine whether the relevant socio-political environment could hold any clues. However Mukherjee feels able to conclude definitively definitively on the identity of his wall painting whereas Sengupta having considered all aspects of his stone image does not. There is wisdom in both conclusions. Also though focusing on opposite ends of south Asia Mukherjee and sengupta appeal to principles dear to Bhattacharyya academic life, Mukherjee insisting that we look outside the Indian sub-continent to central Asia for clues to what became known as Indian goddess worship and Sengupta offering a close regional reading of one district in Bhattacharyya home state.

Our final essays in Part IV share a common interest in power the transformations possible though sakti and through the Goddess as Sakti in the experience of Hindu men and women. In a Festival for Jagadhatri and the power of Localized religions in west Bengal Rachel fell McDermott focuses on Jagaddhatri a goddess of immense importance to several towns and small cities in Hooghly Howrah and Nadia districts where her annual festival modelled on that of Durga but occurring exactly one month later is the height of the religious calendar. A deity of the high Sanskritic and Puranic tradition who was localized in the eighteenth century by a wealthy Sakta Zamindar (landowner) Jagaddhatri is now worshipped in carnivalesque public displays that rival Durga festival in opulence and her realms of devotion blood sacrifice and political clout recently it has extended even further to localities in the diaspora where Bengalis turn to her for and in identity formation.

The power that informs the topic of Jeffery kripal essay by contrast is Tantra. In shashibhushan Dasgupta Lotus: Realizing the sublime in contemporary Tantric studies Kripal employs the lens of sublimation to provide a bridge of understanding between psychoanalysis and Tantric. He argued that both systems prescribe the creative transformation of sexual energy and that psychoanalysis can poetically be described as a kind of Western Tantra as a century long meditation on the powers of sexuality the body life death and religions. This proposal is part of Kripal ongoing project to brings the insights of Sakta Tantra and psychoanalysis into fruitful and mutually illuminating conversation and although this essay will not be uncontroversial it is consonant with Bhattacharyya own conviction that eroticism and sexuality are closely entwined in Indian religiosity.

The last two essays in many belong together. Miranda Shaw and Cynthia Ann Humes both examine the implications of south Asian conceptions of divine females in the lives of south Asian women and arrive at radically different conclusions. In Magical lovers sisters and mother; Yaksini Sadhana in Tantric Budhism Shaw investigates Buddhist Tantric texts invocation in Tantric meditation of a class of powerful alluring fertile and potentially dangerous female spirits who are said to act as the aspirants wives or lovers. She then postulates that positive conceptions about the Yaksini may have influenced attitude towards the Tantrika actual female ritual partner or dakini the Vehicle for his spiritual transformation. This essay builds upon shaw prior work on accomplished women in the Buddhist Tantric tradition and aims to recover women agency in a hitherto and wrongly assumed patriarchal context. Humans findings are not so idealistic. Drawing on fieldwork conducted among patrons of the goddess temple at Vindhyachal in North India in the power of creation Sakti women and the Goddess she notes that the conception and adoration of divine females such as the goddess Vindhyavasini worshipped there do not necessarily translated to the extension of positive conceptions of female empowerment in the lives of most south Asian women. Her study is a fitting conclusion to the volume for it is intentionally informed by and engaging of Narendra nath writings. She considers his many statements about agriculture metaphors in early Hindu text that draw comparisons between soil and women and link procreative power with social power his theories of dependent and independent Saktism his distinctions between virgin goddesses as well conversation she held with him during her time in India conducting fieldwork.

Apart from the four broad topics or parts into which these essays are divided there are at least six other cross cutting themes characterizing the work of the volume twelve contributors; (1) Brighenti Humes and McDaniel echo Bhattacharyya advocacy on behalf of the politically of ritually disadvantage whether these be tribal low cast women or Tantrikas; (2) Coburn Gupta, Humes, Roy, and Shaw all challenges received wisdom about gender hierarchies even if they do not come to the same conclusions about the usefulness of feminist analysis; (3) Brighenti, Kinsley, Kripal, McDaniel and Shaw discuss Tantria and sexuality Brighenti highlighting its connection to ritual violence and the other four arguing that the erotic aspects of the Sakta tradition should be valorized not vilified; (4) Bhattacharyya commitment to the inclusion of Buddhist and jain materials in surveys of Indian history is shared by coburn who sees parallels in Buddhist and jain stories about Sita with that preserved in the Adbhuta Ramayana Sengupta who looks to Jain goddesses as possible clues for the identification of his Raiganj image and shaw shoes area of expertise is the Buddhist goddess tradition; (5) McDaniel, Mcdermott and sengupta have chosen field sites to the elucidation of a local history that was dear to Bhattacharyya own heart and (6) although all of our contributors are conversant with Western theory Humes and kripal in particular have witten hermeneutical ideologies. Bhattacharyya we hope would be gratified by the many ways in which his intellectual heirs have charted paths along routes similar to his own.

Breaking Boundaries With The Goddess: Future Study of Saktism

As we have seen each of the essayists in this volume urges those of us engaged in the study of Saktism to push out in new directions: to examine texts for new meanings even if these conflict with cultural or sectarian truths as defined in dominant Brahmanical and linguistic to clarify modern phenomena; to listen in fieldwork to the politically disenfranchised and argue for the importance of their perspectives if necessary criticizing Western and Indian prejudice to employs a hermeneutic of empathy validating Sakta and or Tantric beliefs and rites; to seek fearlessly to understand the relationship between goddess and women no matter what one hypothesis to make bridges between eastern and western analytic categories to break out of geographic narrowness to embrace a global perspective beyond the Indic subcontinent and to be humble enough to conclude when appropriate that one cannot answer all questions.

As volume editors we would like to propose some even broader changes or improvements to our field of interest changes that may require too much money or time to be immediately feasible but that are nevertheless worth wishing for.

First we could all benefit tremendously from the editing printing and translating of more Sakta texts. These could be published in paper form but just as useful would be the development of a collaborative centralized and computerized database of ongoing translation projects. The same is true of images and we commend the American Institute of Indian studies for its mammoth image bank project in India. Imagine the usefulness of such a resource to an art historian like Sengupta endeavouring to chart the iconographic development of a particular south Asian deity.

Continuing the emphasis upon fieldwork is a second clear priority close studies of sectarian communities temples pilgrimage sites or political groups for whom the Goddess in some form is a rallying cry. Such research adds depth to scholarly understanding and perhaps most significantly reduces the risk of naive theoretical or textually grounded postulations. Given the heightened reliance by current nationalist Hindu Political parties on the figure of Bharat Mata or Mother India as a means to stir patriotic fervor we expect that Sakta symbolism will play an increasingly visible role in public debates on the nation.

Collaborative research is a third prime desideratum. This could occur between scholars who though working in different geographic areas of the subcontinent and with different geographic areas of the subcontinent and with different linguistic skills are already concentrating on the same goddess or the same interpretive question. They could come together for a year to form a think tank on a particular theme or issue that required the expertise of all of them. How for example it the Kali of Kashmiri saivism? Or how might we erase strict lines between Buddhist Jain and Hindu categories in order to understand early goddess questions. Indeed joint Projects even though they are not rewarded in the current university system which values single authored works are terribly important for the advancement of knowledge in the field of Saktism as its boundaries are so porous and its historical trajectories still so unknown. The field of religion as a discipline already draws upon the methodologies of anthropology art history folklore history psychology and sociology such linkage need to be made more explicit through active collaboration and interchange. The same can be said of dialogue on an international scale we need more conferences where scholars from India, Europe, Japan, and the American are involve and more granting agencies willing to fund them. In terms of access to published research the English speaking world is unfairly privileged yet the inability of most scholars of South Asia to read Russian or Japanese for instance means that much excellent work in our field remains inaccessible.

Our final suggestion for future work is the inclusion of the South Asian diaspora in the consideration of Sakta history and religiosity. And here we intend not only diasporic sites such as for example the Lakshmi temple in Asland outside of Boston the Kali temple in Toronto or the Durga Puja celebrations in Tokyo but also the south Asians who frequent them. Most of us outside the subcontinent who teach about Sakta goddess tradition find our classes increasingly populated with first second and third generation south Asians: their hybrid perspective on the home culture as well as their participation in recreations of that culture in the diasporic setting can teach scholars much about the flexibility and malleability of goddess centred communities. Perhaps more such student will themselves join other diaspora scholars in the field enriching the conversation even further.

In sum the best way to honor the multifarious ever creative and transformative Goddess and her traditions in the subcontinent is to be receptive to new perspectives new research techniques and the insight derived from new collaborations. This is also the best way to pay affectionate tribute to Narendra Nath Bhattacharyya whose academic career was characterized by openness: in his intellectual curiosity in his advocacy for the vilified or neglected and in his affable collegiality.

| List of Illustration | IX | |

| Acknowledgments | XIII | |

| Note on Transliteration | XV | |

| Introduction | XVII | |

| Part I: Surprising Finds in Familiar Texts | ||

| 1 | Engendering Alternative Power Relations: The Viraj in the Vedic Tradition | 3 |

| 2 | Once Upon a Time the Supreme Power: The Theological Rise and Fall of Laksmi in Pancaratra Scriptures | 15 |

| 3 | Sita Fight while Rama Swoons: A sakta perspective on the Ramayana | 35 |

| Part II: Rethinking Blood, Cadavers, And Death | ||

| 4 | Tradition of human sacrifice in ancient and tribal india and their relation to saktism | 63 |

| 5 | Sitting on the Corpse's Chest: The Tantric Ritual of Sava Sadhana and its variations in Modern Bengal | 103 |

| 6 | Corpses, Severed Heads and Sex: Reflections on the Dasamahavidyas | 137 |

| Part III: The Contributions of Art History | ||

| 7 | The Northernmost Representation of an Indian Goddess of Power | 163 |

| 8 | An Unnoticed Form of Devi From Bengal and the Challenges of Art Historical Analysis | 177 |

| Part IV: Experiencing Sakta Power | ||

| 9 | A Festival for Jagaddhatri and the power of Localized Religion in West Bengal | 201 |

| 10 | Shashibhushan Dasgupta Lotus: Realizing the sublime in Contemporary Tantric Studies | 223 |

| 11 | Magical Lovers, Sister, and Mother: Yaksini Sadhana in Tantric Buddhism | 265 |

| 12 | The Power of Creation: Sakti, Women, and the Goddess | 297 |

| Select Bibliography | 335 | |

| Index | 359 | |

| List of Contributors | 385 |