Classical Indian Dance in Literature and the Arts

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDK224 |

| Author: | Kapila Vatsyayan |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2022 |

| ISBN: | 9788124611449 |

| Pages: | 574 (Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.50 X 7.50 inch |

| Weight | 1.43 kg |

Book Description

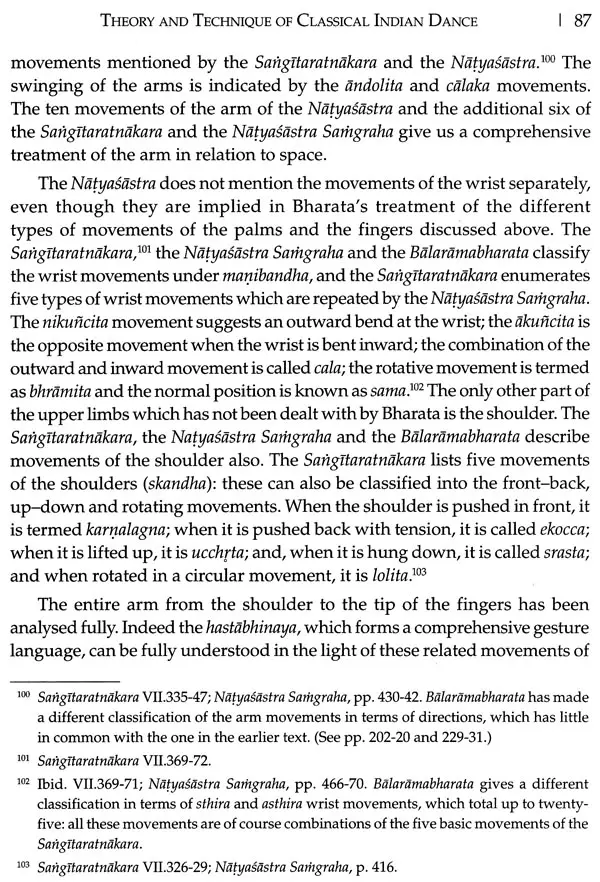

This volume is the result of many years of painstaking research in a field, which had been neglected by art historians, and thus presenting an idealistic view of the whole tradition of Indian art and aesthetics. This definitive work on the inherent interrelationship of the Indian arts is a pathbreaking endeavour, treading into a domain which no one had explored. For that to happen, the author has delved deep into enormous mass of literature on the subject and has also surveyed the portrayal of dance figures in ancient temples. With Dr Kapila Vatsyayan's profound knowledge of various dance forms as a performing artist of her own standing and having studied the sculptures and artefacts minutely, the book emerges so scholarly emanating the wisdom and know-how of a persona, endowed with the unique combination of a researcher, an art historian and an aesthetician par excellence.

The book vividly presents, analyses and critiques the varied facets of Indian aesthetics, especially the theory and technique of classical Indian dance, while doing a penetrating study of interrelationship that dancing has with literature, sculpture and music. In doing so, it surveys and analyses the contribution of great Sanskrit authors, theoreticians, playwrights of ancient and classical India such as Bharata, Bhasa, Kalidasa, Sudraka, Bhavabhuti, Abhinavagupta, Jayadeva and many more along with numerous Bhasa scholars of arts, aesthetics and literature, covering each and every nook and corner of the Indian subcontinent.

This highly scholarly work should invoke keen enthusiasm among Sanskritists, art historians, dancers and students of varied art forms alike, and should pave the way for ongoing researches on all the topics covered within its scope.

Dr Kapila Vatsyayan (1928-2020), was a foremost art historian, an eminent philosopher of modern India, an aesthetician par excellence, educationalist, a parliamentarian, policy-maker and a prolific writer. She played a lead role in founding the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) and served it as Director. A multi-faceted personality, Dr Vatsyayan taught at the University of Delhi; was Joint Secretary, XXVI International Congress of Orientalists; and Joint Educational Adviser, Department of Culture, Government of India. She was also a Jawaharlal Nehru Fellow. She was an elected Fellow of the Sangeet Natak Akademi in 1970, and represented India in many international conferences, symposiums and expert meetings, practically all over the world. In 2011, she was bestowed upon The Padma Vibhushan Award.

With degrees in English Literature, Art History and Education and Indology from Delhi, Michigan and Benares universities and doctorate in Art History from the Banaras Hindu University, and long years of training under India's most renowned scholars like Vasudev Saran Agarwala and dance gurus like the late Achhan Maharaj, Amobi Singh and Juana Laban, she combined in her person a mind deeply rooted in tradition and the skills of exacting scientific analysis with a rare capacity of correlating theory and practice, the literary plastic and performing arts.

Her works include Dance in Indian Painting; Human Development in Indian Perspective and Other Essays; Indian Classical Dances; India's Cultural Heritage and Identity and Other Essays, Metaphors of the Indian Arts and Other Essays; Ramayana and Arts of Asia; Role of Culture in Development; Some Aspects of Cultural Policies in India; The Square and the Circle of the Indian Arts; Traditional Theatre: Multiple Streams; Traditions of Indian Folk Dance and General Editor of Prakyti the Integral Vision (5 volume set).

The present study is the result of some fifteen or more years of labour in a field which has, perhaps because of its very nature, received inadequate attention in the past. As a practical student of classical Indian dance forms I had found it necessary to examine and understand the theoretical bases on which the tradition of the dance and the traditional techniques had been built. The gurus and masters, hereditary repositories of what were unquestionably the authentic traditions and techniques of Indian dancing, could only provide inadequate or unsatisfactory answers to many of the theoretical questions that arose in mind. This impelled me to conduct my own research into the original texts. The relationship of the arts, I thus observed, and the insights I gained encouraged me to pursue the detailed study of the field which forms the subject of the present work. I consider it my good fortune that I should have been led to the subject by what may appear an indirect route, because without this practical background I would have found it far more difficult to reach the bridge from the theoretical tenets to the vast and varied field of their application to dance practice. It is the discovery of such bridges and the clear demarcation of routes across them that has been my chief purpose in the present study. I may be permitted to express the belief, in all humility, that the purpose has been achieved. I trust that the lines of study indicated here will be extended to other fields which are, as I have attempted to demonstrate, inseparably related.

The size and nature of the field was formidable and I had naturally to restrict myself to what could be spanned by a unified study. Geographically its scope extended from Manipur to Gujarat and from Hohen-jo-daro through Khajuraho to Kerala. It was not only the archaeological sites scattered over this vast area or the objects recovered from them that had to be surveyed. The different local traditions of the schools of classical dancing preserved in isolated pockets throughout the country had also to be studied; and patient solutions found to intricate problems through personal contact with ageing gurus who represented the precious oral tradition of classical Indian dancing and who alone could provide the insight which would illuminate a study of so complex a field.

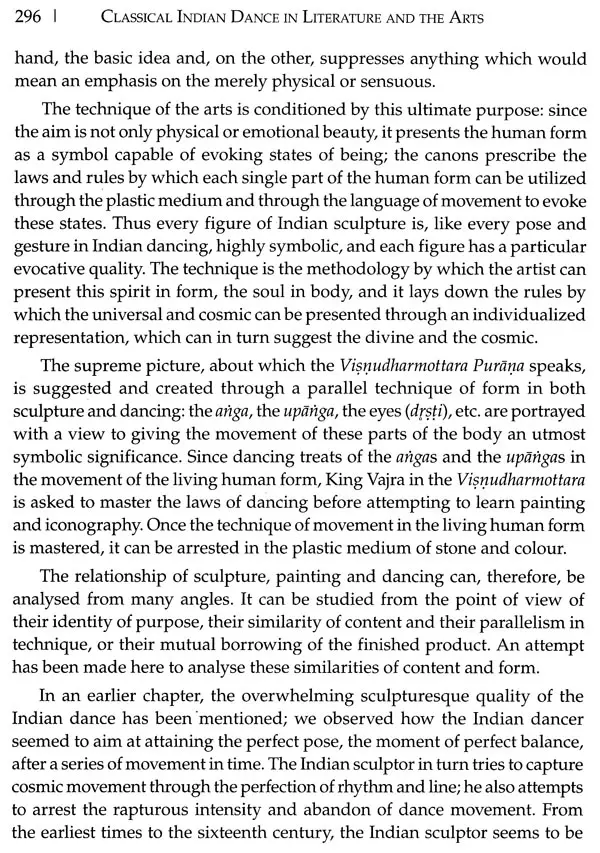

While the rasa theory is common to all Indian arts, a parallel study of the different art forms in relation to this theory has not been undertaken before. Indeed, it may justifiably be said that western scholars and art critics have generally devoted greater attention to the continuous study of the theoretical foundations of artistic practice than has been the case in India. Of course, to a large extent, this has resulted from the very nature of western and Indian artistic theories. In the west, the theoretician as well as the practicing artist in every field of art including literature has been actively concerned with "significant form" and has therefore generally studied several arts together or in relation to one another. In India, however, because of the emphasis placed by the rasa theory on the evocation of a mood or the attainment of a 'state of being', both the artist and the theoretician have tended to be concerned primarily with technique. This concern with technique has tended inevitably to isolate one art from another because techniques are specific and exclusive.

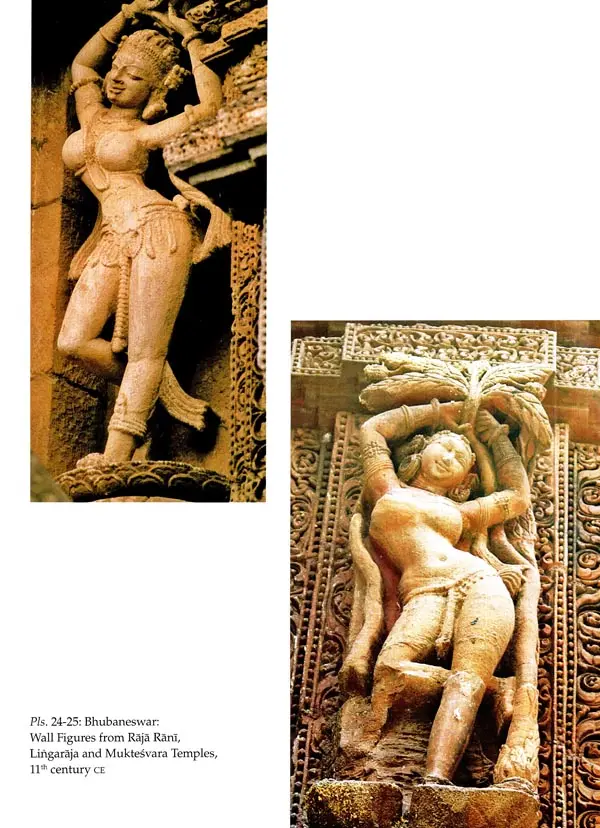

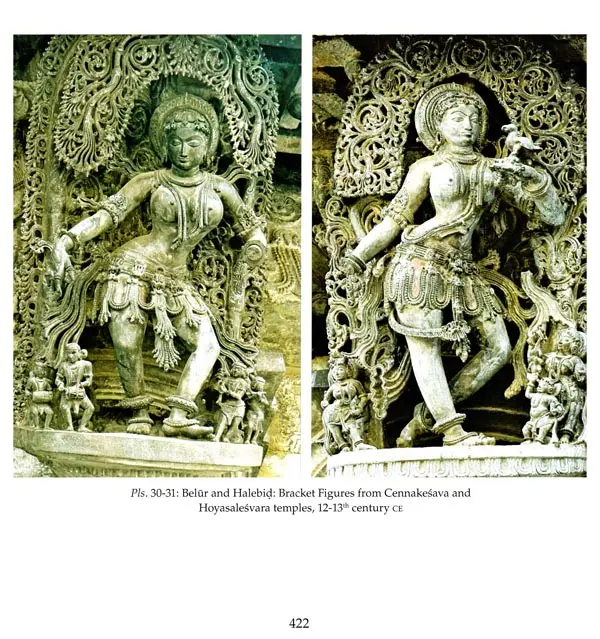

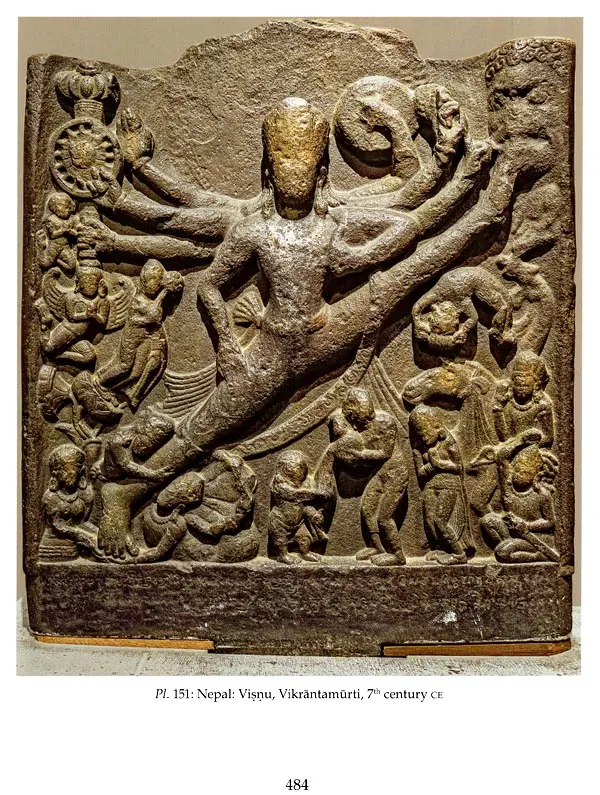

While the present study has, I believe, provided the groundwork for a complete historical study of classical Indian dancing and the evaluation of its different forms, the limits within which I have worked must here be clearly stated. I have dealt, in some degree of detail, with literary and sculptural material upto the medieval period. It would be logically consistent to continue this study into the beginning of the modern period, and it is my hope and wish that such a study will be undertaken in the near future. But it is obvious that this would require the collaboration not only of a large number of individual workers but also of regional institutions. Since from the medieval period onwards the unity provided by the Sanskrit It has been a part of my good fortune, referred to earlier, that in the course of practical training in the different dance disciplines, I have been able to establish contacts with and receive valuable guidance from a number of gurus of dancing and ustads or heads of gharanas of music, and I have naturally profited by the material thus made available. But obviously, a history of the theoretical foundations of Indian dancing cannot rely on such fortuitous circumstances. Most of my literary and sculptural source material is known. My purpose was not so much to bring new material to light as to organize and correlate the existing material in a pattern of significance for the historical study of the classical Indian dance. In the field of sculpture particularly it was considered desirable to refer primarily to known examples in order to facilitate the main argument. An endeavour has been made to analyse sculptural representations of dance scenes in terms of dance poses and dance movement and thus to establish the close relationship of the two art forms. The use of literary material has been more or less analogous. Though I have considered a number of unpublished manuscripts relating to dance in Indian libraries and abroad, I have based my argument in the main on published works. I would have liked to include in my examination some recently published manuscripts, specially Jayasenapati's Nrtta Ratnavali and the Sangitaraja and some other works published in Orissa, Andhra Pradesh and Assam. It was not possible to do so because the press copy had already been handed over and the Press was unable to cope with additions during the years that the book awaited publication. THE present study is an attempt to investigate the nature and extent of the part played by other arts, especially literature, sculpture and music, in the development of Indian dance and to determine the role of dance in these arts. Since all classical Indian arts accept a common theory, which they faithfully follow, the attempt has necessarily involved a review of the fundamental principles of aesthetics which have governed the practice of these arts for fourteen centuries or so. Thus the scope of this presentation is: (i) to give a general idea of the aesthetic theory common to literature, poetics, dramaturgy, sculpture, painting, music and dancing; (ii) (a) to analyse the theory and technique of classical Indian dancing, with particular emphasis on the significance of symbols and symbolization, (b) to trace the history of the theory of dance as formulated in the Sanskrit texts from the Natyasastra to the Balaramabharatam, and (c) to analyse the conscious attempts to represent and illustrate dance movements in sculpture, as in the Cidambaram Temple (Nataraja Temple); (iii) (a) to analyse the references to dancing in the creative literature (kavya) of Sanskrit from the early Vedic texts to the late medieval dramatic works (thirteenth-fourteenth centuries), (b) to identify the general and more particular forms of dancing pre- valent in different periods, and (c) to establish the close relationship between dance and drama and to see how the technique of dance affects the dramatic technique of the classical drama; (iv) (a) to analyse the treatment of the human body as form in Indian sculpture and dancing, (b) to interpret the concepts of mana, satra and bhanga as principles of space, mass and weight manipulation, (c) to review the yakṣt and salabhatjika motifs as figures representing dance movement in Indian sculpture, and (d) to analyse the dance scenes in sculpture in terms of the technical terminology of dance as enunciated by Bharata; (v) to trace the history of dance through pictorial evidence from the earliest murals to medieval miniature painting tradition; and (vi) to consider the general principles of Indian musical theory and musical composition in their bearing on classical dance composition. The sources utilized for this study are the Sanskrit texts from the Rgvedic period to the fourteenth century and the examples of Indian sculpture from the earliest figurines of the Indus Valley to medieval sculpture in the field as also in collections. No attempt has been made to extend the study to the material available in regional languages. **Contents and Sample Pages**