Conversations with Mani Ratnam

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAG635 |

| Author: | Baradwaj Rangan |

| Publisher: | Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2013 |

| ISBN: | 9780143421108 |

| Pages: | 350 (Throughout B/W and Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 9 inch X 6 inch |

| Weight | 550 gm |

Book Description

About of the Book

Mani Ratnam’s Nayakan is among Time’s ‘100 Best Movies Ever’; and his Raja launched A.R. Rahman. For the first time ever, Mani Ratnam opens up here, to Baradwaj Rangan, in a series of freewheeling conversations-candid, witty, pensive, and sometimes combative-and looks back at these and nineteen other masterly films. With Rangan’s personal and impassioned introduction setting the Tamil and national context of the films, and with posters, script pages and numerous still, pages and numerous stills, Conversations is treat for serious lovers of cinema as well as the casual moviegoer looking for a peek behind the process.

Foreword

In my teens, in the 1980s, I grew up in awe of Hollywood. David Lean, Steven Spielberg, Ridley Scott and film-makers like them. But when I started watching Mani Ratnam’s films, my loyalty changed. I saw that this man directed moving and sensitive films that were rooted in my own culture, and they had an almost unreal quality, which made me feel good. What better thing could happen in my life than if this same film-maker, whom I admired from a distance, came asking me to compose music for his next film? I never thought that this would happen.

I met Mani Ratnam while he was planning Roja. At that time, I was discovering my Sufi zone and, in many ways, didn’t care about failure or success. I was happy and sad, all at the same time. So when he came to me in my modest studio, back in 1990, I didn’t want to feel overjoyed, because if he didn’t like what I had done, he could throw the music at my face and leave. I was prepared for anything, but things worked out. We worked together closely and made the Roja soundtrack with a kind of unique creative energy.

Mani Ratnam, whom we all call ‘Mani Sir’, became a great friend. He carefully selected the pearls in me and made a garland of them. Until three or four years ago, I would send him every album, like a student seeking his guru’s approval. I used to call him and ask him what he thought about almost every song that I composed, whether they were for him or another director. Sometimes he would say, jokingly, ‘It’s fantastic. Why don’t you give it to me?’ At other times, he’d say, ‘No, it could be better. You could try this, you could try that.’

As the years passed, I realized that he is one of the key people in my life to have triggered my imagination. Gaining knowledge is easy. You can read books. You can learn by working with someone and observing what he does. But very few people push you and say, ‘This is not good enough; you can go much further.’ His advice never made you feel like a subordinate but sounded more like encouragement from a friend. That’s a great quality in him. He’s not like a teacher, but like co-worker and co-creator-someone exploring ideas with you. As we worked together over the years, we discovered many things. We knew, for example, that we needed a track like Humma bumma in order to include a song like Keima hi kya, because a film’s soundtrack cannot sell on melody alone. That’s something we came to understand-the mixed moods that an album has to offer.

When you’re in the movies, people respect you so much. Even your family can start regarding you differently. You can get it all, and you could lose it. Suddenly the ground beneath your feet could disappear and you could fall, and people could move away. Very few people value the real you. Most people value a side of you, which is more or less false. With Mani Sir, even if you fall out of favour with the box office, he sees you for what and who you are, and respects you in much the same way that he always had. He has the same attitude towards actors, cameramen and all the people he works with. That’s a great quality, and in my experience, few have this quality.

In the journey of exploring art, allowing one to make mistakes in ones work is very important. It makes one grow creatively. It needs courage. Some directors are very successful making the same kind of film, but in the long run we do not respect them as much. Here’s a man who wanted his style of stories to have commercial success, yet unafraid to sometimes fail. And because of that, he has kept growing from film to film.

Though a lot has changed now, people here in India had a different mentality from those in the West those days. Not many people here wanted to push themselves in order to excel at something. They were satisfied with okay stuff. So I really, really respect people like Mani Sir who had raised the bar here, in those conditions with our limited resources and technological talent.

I think it’s great that Mani Ratnam has spoken to Baradwaj Rangan about his work and in so much detail. One of my friends has taught me an Italian word, sprezzatura, which refers to making the most complex thing look simple and easily doable. While other creators make a big show of their art, Mani Sir makes it look as if anyone can do what he does. Though it’s really not that simple.There’s so much thinking, craft and sensitivity that goes into his work. I am still seduced by portions of his work in Iruvar, Nayakan, Dil Se, Guru, Bombay and his latest offering Kadal.

I try to be a man of faith. And here is a man who’s an atheist by choice. We coexist as opposites. When I have a problem, I think that tomorrow will be better; that’s because of my faith in spirituality. But what does he do? I wonder about this. But what connects us is the humanity in him and his movies. Personal tragedies in the past had demotivated him a little and slowed him down. But he was strong enough to survive it. It is difficult for me to say whether I admire him more as a film-maker or as a person.

Introduction

Some months after I began working on this book, after the initially awkward and nervous meetings with Mani Ratnam had steadied into reasonably confident conversations, I ran into the directorGautham Vasudev Menon. We talked about this and that, the generalities that unite two professionals plying their trades at opposing ends of the cinematic spectrum-him the maker, me the masticator-and then, for some reason, I told him about the book and about meeting Mani Ratnam for the first time in his office at Madras Talkies, where he spoke to me and I spoke to the table in front of him. Instantly-and if only for that instant-Menon and I were bonded in a secret brotherhood. He laughed and said he wasn’t surprised. He had done the same thing when a hero he’d sought out for a project had dispatched him to Mani Ratnam’s office to narrate the screenplay. ‘I couldn’t look at him’ Menon said. ‘I mean, how can you? He’s the man who made Nayakan.’

Perhaps acknowledging the powerful seductions of the cinema, almost every city, at some point, has had a movie hall named Eros. The one in Madras was on LB Road, on a plot that, today, houses a shiny showroom for the kind of foreign car that people those days could drive only in their dreams. But even in the early nineteen-eighties, when pachydermal Ambassadors lumbered down roads too tiny to contain them, Eras was crumbling. A faded art-deco facade opened out to an absurd excuse for a snack counter, with pre-sealed packs of popcorn and cloudy glass jars stocked with palm-sized packets of roasted gram speckled with an evil-looking spice. Inside, where air conditioning would have necessitated a drastic revision of the ticket price of two-something rupees, the task of circulation was entrusted to fans, drooping from the ceiling on long stems and pressed reluctantly into service, like a napping child roused and ordered to fetch a bunch of bananas from the stall down the street.

I bring these things up not to wade in nostalgia for an India that bears little resemblance to the country today, whose cities boast the biggest of buildings with the finest of facilities. I bring this up because-despite the stale snacks, despite the strangulating heat, despite handed-down prints that flickered as if possessed by the ghosts or a thousand Previous projectors-this long-dead theatre Willnever me In my memories. This is where, in 1985, I saw my first Mani Ratnam movie. It was Idhayakoyil, the director’s fourth film, and the one that he considers his worst. I saw it three times.

I wish I could say that I recognized, before anyone else, a titanic talent submerged under the wreck of this melodrama about thwarted eros, with a singer pining for a long-dead love (who will never die in his memories) and spurning the young woman who falls for him. But the reasons for my repeat viewings were probably the presence of Ilaiyaraaja’s marvellous music and the absence of 24-hour TV, which meant that instead of flipping through channels and landing on a movie we felt like watching, we went to the theatres next door and saw the movies that were showing, like PagalNilavu, which Mani Ratnam had made earlier. This time, too, the earth didn’t move. But the release of Mouna Raagam, the next year, brought to Madras some mild tremors, which, by the director’s next movie, Nayakan, intensified into a full-blown quake that reshaped the landscape of Tamil cinema.

Even today, twenty-five years after the release of Nayakan, some of us remember our experience of the film as if we’d unknowingly stepped into the competition ling at a village fair and ended up flattened by the local wrestler. We couldn’t move, we couldn’t speak-during the film and even afterwards, as we lurched back home in a late-evening bus, too stunned to slip into the genial ritual of post-movie analysis, too numbed by the serendipitous shock of stumbling into a moment that would forever alter our expectations of Tamil cinema. We knew we could no longer resign ourselves to perfunctory cinematography and tinsel-strewn sets and an incestuous ethos birthed from Tamil films over the years. We knew, now, that we could not only dream about international standards of filmic achievement but also attain them. Today, a quarter of a century older, I realize that we may have overestimated Mani Ratnam and undervalued the impact of the pioneers before him on Tamil cinema, but such is the impetuousness of adolescence. The body blow dealt by the film drove out reasoning and rationality. What was left was pure physical sensation.

At this point, I suppose, I should define ‘we’. I refer to people like me, born in Madras in the nineteen-seventies and ripening into cinematic awareness in the decade that followed, in Mani Ratnam’sdecade. We are possibly the most qualified to write about Mani Ratnam. We might also be the least qualified. Others, born in earlier and later decades, did not feel his impact the way we did, but they, shorn of our hyperbolic adoration, are probably better equipped to pin down his place in the Tamil-cinema continuum. We couldn’t-because to us he wasn’t just a film-maker, he didn’t just make films. Mouna Raagam onwards (and with the grand exceptions of Nayakan and Tbalapatby, which wove riffs around the adult experience), he was a zeitgeist-defining showman who propped up in front of us mirrors into our selves-our young, urban selves. No one, just no one, had put on screen what we thought, what we felt, what we dreamed the way Mani Ratnam did.

Mani Ratnam was certainly not the first film-maker who animated his films with the lifeblood of the young. During the course of these conversations, he revealed that he grew up in thrall to the taboo-splintering dramas of K. Balachander, so attuned to the rebellions of youth, and before KB, there were directors like Sridhar who, in the nineteen-sixties, bequeathed a youthful exuberance to films like Kaadhalikka Neramillai, a two-and-a-half-hour romantic romp, which belied a title that sighed that there was no time for love. But, among other things, the girls in Sridhar’s movie threatened to burst out of salwar kameezes glued to their zaftig frames. This enslavement to voluptuousness was our parents’ youth, not ours. Our fantasies were forged over visions of a sylphlikeAmala in a pink sleeveless top, swaying to music from her Walkman, as the backlighting bestowed on her an entirely warranted urban- goddess aura-and if there’s another artifact of pop culture that hotwired itself into the very being of the Tamil youth the way Agni Natchatiram did, I’m not aware of it. Call it solipsism, call it tunnel vision-I call it the unvarnished truth.

The sun that you saw in the opening credits of that film, scudding through clouds into a clear sky and blinding the screen with its brilliance-there was no better visual metaphor for the Mani Ratnamof the era. He was dazzling us with the trail he was blazing, and we were the first to see the light. Just as words bind themselves better to pristine parchment than to palimpsests, his images sank into our souls. (The older generation, having watched a lot more cinema, and having weathered a lot more trailblazing in the movies, was more guarded about welcoming Mani Ratnam, as if to embrace him would be to wallow in the shallow pools of youthful faddishness. It was a while before they realized that Mani Ratnam was no fad, that he was here to stay, and that he would go on, after Raja, to make the kind of movies that they wanted him to make, and that, in a sense, he’d become them.) Hence my claim that no one knows-or feels about-Mani Ratnam the way we do.

That scene in Agni Natchatiram where Harold Faltermeyer’s theme for Beverly Hills Cop bounces off the walls as Amala and her girlfriends anticipate their first taste of nicotine with stolen cigarettes-that was us. That was the garish synth music that blared from our two-in-ones.That was the forbidden-forest fascination that cigarettes held for us. Mani Ratnam didn’t judge smoking-and if this made him irresponsible in the eyes of the grown-ups, it only made him cooler to us. Most film-makers, then, were adults who’d left their youth far behind, and their portrayals of the young harked back to their times. Mani Ratnam, on the other hand, seemed to be one of us, someone who, in front of his parents, would pore over cyclostyled sheets from Brilliant Tutorials over late-night cups of tea from a thermos-only, hidden in those impenetrable thickets of IIT problems would be a comic book or a much-thumbed copy of Debonair magazine. With his depiction of the youngsters in Agni Natchatiram and the films that followed, he seemed to completely get us.

He seemed to get that school isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be when the youngest sister in Mouna Raagam wanted Revathy to get married on a weekday so she could bunk classes. He seemed to get that virginity isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be when he unleashed a waggish scene in Agni Natchatiram with an unmarried Nirosha walking into Karthik’s house and confessing, in the presence of his comically horrified family, to being pregnant. He seemed to get that respecting elders isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be when the little girl in Anjali, in the midst of a heated family argument on the building’s staircase, urges her father to shout back and silence the bald neighbour asking them to take their dirty laundry indoors. (A mere translation does little justice to the level of disrespect in her choice of phrase: ‘Saridhaan poda, sotta thalayaa.’ Get lost, baldie!) He seemed to get that happily-ever-after isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be when he had Nirosha reveal, in Agni Natchatiram,that the older man she was dining with wasn’t her father but her mother’s second husband, while her biological father lived someplace else with his second wife. He seemed to get that idealism isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be when, again in Agni Natchatiram, Karthik, desperate to locate Nirosha’s address using the numbers on the licence plate of her car, qualmlessly bribes a clerk at the transport office.

But it wasn’t just the subversive excitement of raising the middle finger to the establishment. Mani Ratnarn’s early cinema, simultaneously, had its feet planted on the unshakeable ground of that very establishment. Prabhu, in Agni Natchatiram, was an Assistant Commissioner of Police. We were being told that it could be a nice thing, a cool thing even (with those Aviator sunglasses), to serve the government-that it wasn’t just about becoming an engineer or a doctor or a chartered accountant, which is what our parents, mired in middle-class mores, wanted for us. In the same film, Mani Ratnam had Vijayakumar, the IAS officer, in a dhoti all through, and showed us, long before P. Chidambaram began dropping into our living rooms on national television, that you could make a quiet statement with four yards of crisp, starched cotton-that it wasn’t always about slacks and shirts and a tie dropping from the collar. He had Revathy travel in a local bus in Anjali and he made the youngsters take local trains in Agni Natchatiram and showed us that public transport wasn’t Beneath our dignity-that you didn’t become any less because you didn’t zip around town on a moped or in a car like the rich kids.

Contents

|

| Foreword-A.R. Rahman | Viii |

|

| A Note-Mani Ratnam | x |

|

| Introduction-Baradwaj Rangan | xi |

| 1. | Pallavi Anupallavi, Unaru, Pagal Nilavu, Idhayakoyil | 1 |

| 2. | Mouna Raagam | 30 |

| 3. | Nayakan | 43 |

| 3. | Agni Natchatiram | 67 |

| 4. | Geetanjali | 80 |

| 6. | Anjali | 89 |

| 7. | Thalapathy | 103 |

| 8. | Roja | 119 |

| 9. | Tbiruda Thiruda | 135 |

| 10. | Bombay | 144 |

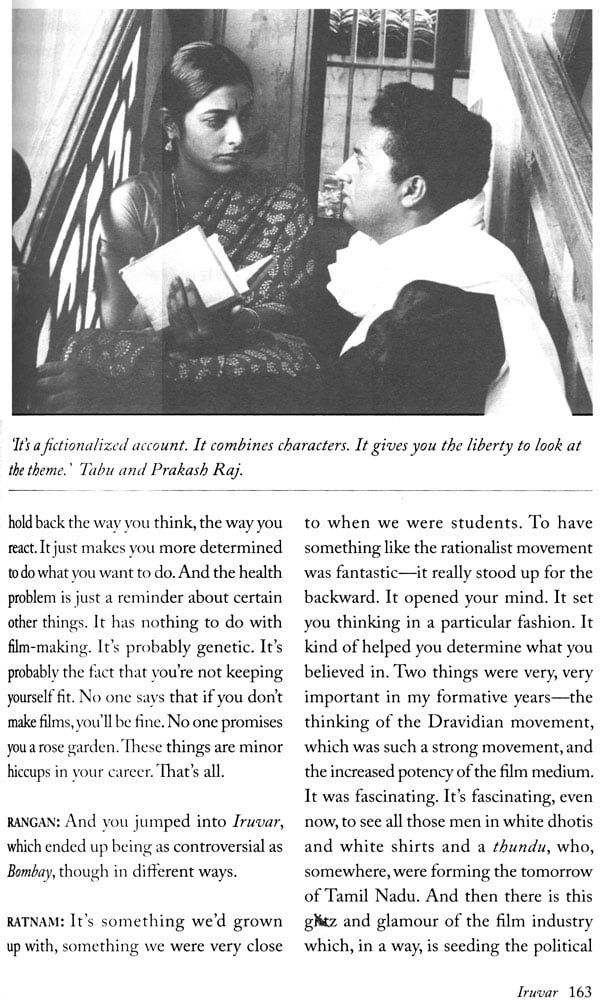

| 11. | Iruvar | 161 |

| 12. | Dil Se | 181 |

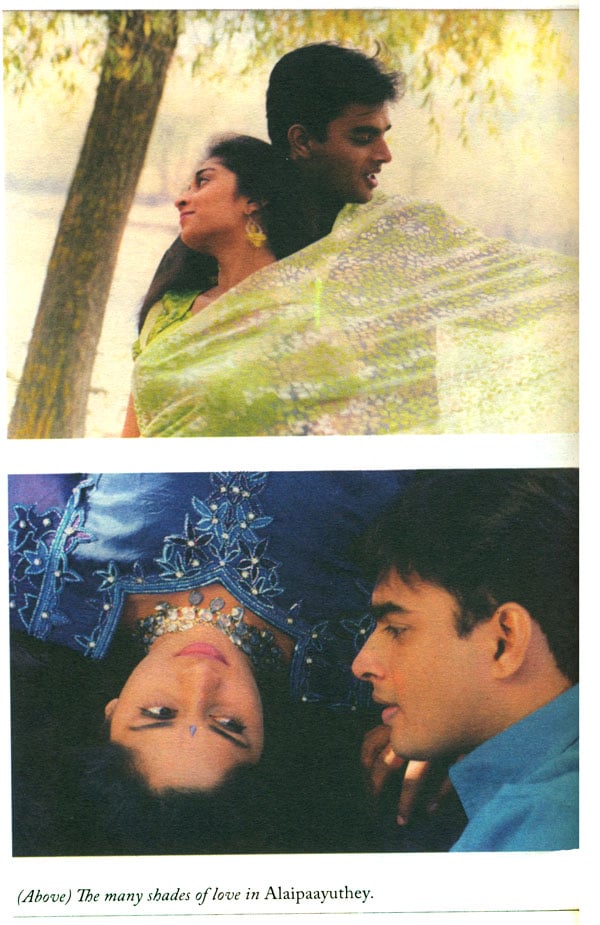

| 13. | Alaipaayuthey | 195 |

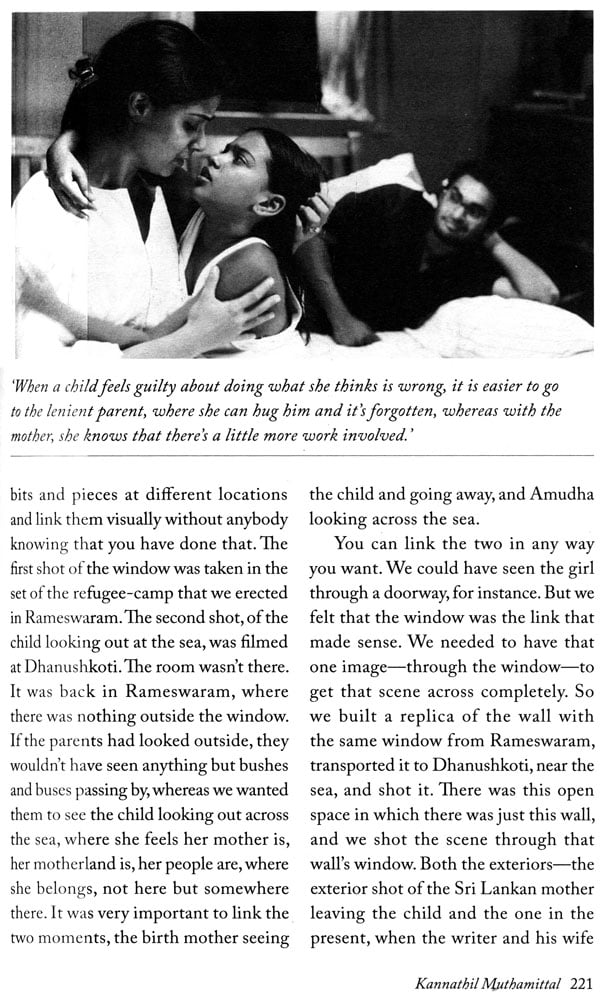

| 14. | Kannathil Muthamittal | 208 |

| 15. | Aayidha Ezbutbu/Yuva | 229 |

| 16. | Guru | 246 |

| 17. | Raavan/Raavanan | 267 |

| 18. | Kadal | 288 |

|

| Filmography and Awards | 311 |

|

| Acknowledgements | 319 |

|

| Copyright Acknowledgements | 321 |

|

| Index | 323 |