Harappan Art

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAF197 |

| Author: | D. P. Sharma |

| Publisher: | Sharada Publishing House, Delhi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2007 |

| ISBN: | 8188934410 |

| Pages: | 368 (Throughout Color and B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 11.00 X 9.00 inch |

| Weight | 1.81 kg |

Book Description

The book Harappan Art deals with the art object in stone, metal, glyptic art, terracotta, jewellery and ceramics. This book is descriptive catalogue data of 200 Harappan objects.

The first chapter is on introduction of Harappan civilization. This includes nomenclature, discovery, extent, chronology, migration, Harappan collection in National Museum, settlement pattern, social stratification, art, craft, seal, religion, burial and decline. The second chapter is on Harappan stone image and here we have catalogue data of 16 images. The third chapter deals with rare copper images. The fourth chapter is on Harappan jewellery items in gold, silver and stone. The fifth chapter is on Harappan glyptic art. The rectangular/ square seals bears negative engraving of script and motif. The sixth chapter is on Harappan terracotta art and this deals with male, female, animal and bird figurines. The seventh chapter is on Harappan ceramics.

Till today we have 2668 Harappan sites and we have excavated 208 sites. The area covered 1.6 million sq. km. by Harappan civilization extended from Suktagendor to Topal and Sanyoli on Hindon in western U.P. and Shortughai in north to Daimabad in south.

Mohenjodaro and Ganweviwala are largest Harappan sites.

Dr. D.P. Sharma did his M.A. in Ancient History, Culture and Archaeology from Allahabad University. He continued his field work and participated in various excavations at Pangoraria, Mansar, Naramada Valley, Bhimbetka Chopani-Mando, Mehgara, Koldihwa, Mahadaha, Ssingaverpur and Bhardwaj Ashram. Besides this, he did extensive exploration in districts of Fatehpur, Pratap Garb, Allahabad of U.P. and Buddhani area of Madhya Pradesh. Another significant contribution of author is discovery of Menander - I (Posthumous) Brahmi inscription from Reh. During 1983-84, he was awarded Commonwealth scholarship and he meritiously qualified M.A. (Archaeology) with specialization on Palaeolithic-Mesolithic of world, from Institute of Archaeology, University of London. He participated in the excavation of Sussex (U.K.) and Pincenvent (France). He has completed D.Phil. research in Allahabad University.

in 1985, he joined as Dy. Keeper at National Museum, New Delhi. In 1993, he was promoted as Keeper in National Museum. At present he is Associate Professor in National Museum Institute and Head of Collection, Harappan and Pre-history, National Museum, New Delhi. He has 20 books and 175 research papers in his credit.

This book deals with the Harappan art of mature Harappan period in stone, metal (copper), glyptic art (seals) and terracotta figurines, jewellery and ceramics. The minor arts of Harappan, i.e. small tiny figurines in ivory, paste faience, shell, lapis, steatite, lapidary (beads), miniature figurines, etc., and other crafts will be included in forthcoming volumes of the author i.e. "Minor Arts and Crafts of Harappan Vol. I, II, III, & IV (Press).

"The present book, i.e. "Harappan art" deals with 200 rare Harappan art objects which include a few rare like a male-torso, bust of a seated priest and a unique bronze dancing girl which are superb examples of Harappan Art. The chapter I covers introduction to Harappan Civilization.

The second chapter of the book deals with the stone images. A few rare stone statuettes from Harappa, Mohenjodaro and Dholavira and polished pillar bases from Dholavira, Harappa, and Mohenjodaro are excellent examples of Stone art and around sixteen rare stone images are described in this chapter. In all among 25 complete stone statuettes have been reported from Harappa, Mohenjodaro and Dholavira among which at least eight examples are noteworthy. The rarest among these are the well-known bust of a seated priest from Mohenjodaro and a similar head-less seated male sculpture of limestone from Dholavira. A priest's head made of steatite from Mohenjodaro also deserves notice. Besides these, there are two rare statuettes made of the jasper-stone of dancer from Harappa while the other is a male torso.

The third chapter deals with a few rare copper /bronze figurines from Harappan sites. The Copper-smiths of Harappan civilization were knowing sinking, raising, running on cold work, annealing, rivetting (SIC), lapping, closed-casting, cire-perdue etc. The Harappan bronze images were mostly mould made by solid cast lost wax or cire-perdue method. The moulds used by copper-smiths range from simple to complex. The example of lapping i.e. joining of various parts of copper/ bronze images had been known to south Asia since last phase of Early Harappan period i.e. Ca 3000 B.C. The copper is a soft metal. Therefore, it was hardened by mixing with tin-arsenic, nickle and lead which produced Bronze. 30% Indus copper objects are bronze alloyed. In these bronze figurines tin alloying ranged from 1 to 12%, arsenic alloying 1-7%, nickle alloying 1 to 9% and lead alloying 1-3%. The earliest bronze, gold and silver objects datable from Ca 3000 to 2800 B.C. were reported from Kunal, Nindowari, Mehrgarh and Nagwada. The world famous bronze dancing no. 1 girl from Mohenjodaro is a superb example of metal art and was recognized as one of the master pieces of Harappan art. The style of a variety of bronze-solid cast animal figurines like elephants, dogs, rams, hares, buffaloes, bulls, rhinos, etc., are superb. The attacking buffalo from Mohenjodaro, the short-horned humpless bull from Kalibangan, couchant hare from Dholavira and three huge animals and chariot from Daimabad are unique examples of metal art and are superior to any metal objects of proto-historic India. Mohenjodaro and Kalibangan bronze bull are identical in appearance. The huge chariot and three animals from Daimabad figures are the biggest and their weight ranges from 15 to 40 kg. The small chariots from Mohenjodaro and Harappa are interesting. The faces of chariot drivers and that of the dancing girl are identical in appearance. Can we call these face of having a proto Austroloid or Dravdian origin ? or African tribal origin.

Fourth chapter is on Harappan Jewellary. The fifth chapter of this book is on the art of Harappan (glyptic art). The seals of steatite bear negative engravings of script and animal motifs. The unicorns and mythical bulls and fish symbols are dominating. The bull figures also appear on these seals. A few of the rare seals of the Harappan show Pasupati Yiva, Pipal, unicorn, man fighting against two tigers or lions, woman catching the tiger and seven sisters. The script of Harappan was most probably proto-Brahmi and this has its origin from the Semetic script of west Asia. The first language of the Harappan population was proto-Dravidian and their second language was Laukik Sanskrit which became popular during late mature Harappan period.

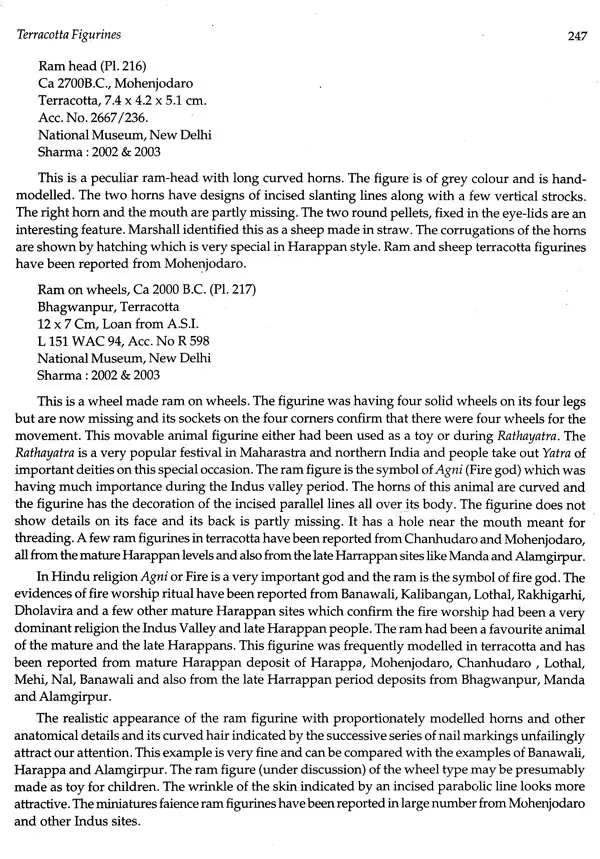

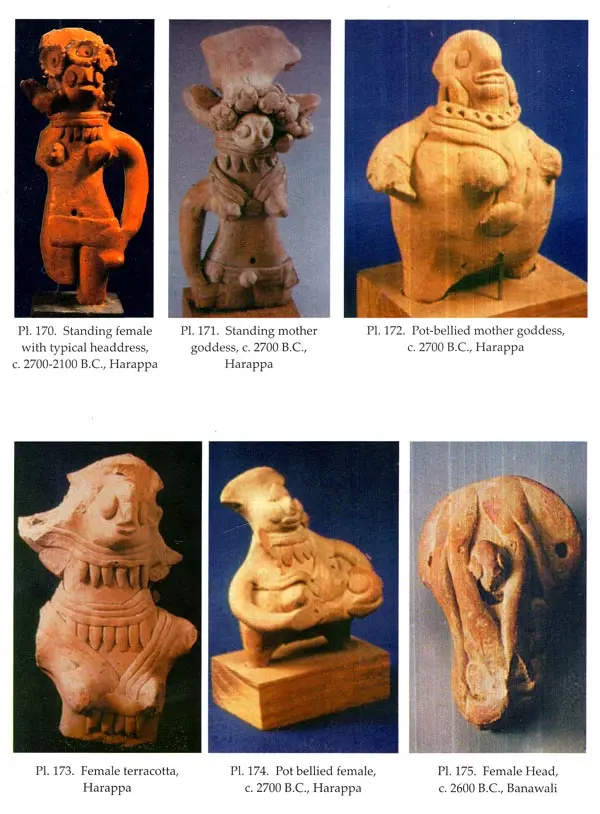

The sixth chapter is on Terracotta art and this is further divided into four sub-chapters. The A part deals with terracotta female figurines and the remaining sub chapters, i.e. B, C, and D. cover terracotta figurines of females, animals and birds. The terracotta figurines of Harappan are mostly hand modelled and only a few are mould/wheel made. After the clay moulding, red or cream slip or wash was applied on these figurines. These clay figurines were fired at very high temperature in reducing condition, i.e. in closed furnace. The colour of the core is mostly red but in some cases it is black. The female terracotta figurines outnumber the male figurines and on this basis we can conclude that the Harappan society was a female dominated society. The female terracotta figurines of Harappan civilization have thin waists, broad-hips with a loin cloth and a gridle, and are adorned with a series of necklaces and head ornaments. The over ornamented female figurines found at places of worship were regarded as Mother-goddesses.

The male figurines are less elaborate and a few mould-made masks or puppets have small goat-like beards and long horns. The tiny male-head and inscribed double headed Sivalinga both from Kalibangan are noteworthy. A few seated male figurines in yogasana from Harappa confirm that yoga was known to Harappans. Some other standing male figurines from Harappan sites are completely nude and a few of them have cut marks on their sexual organs which confirms that some religious rite continued in one group of Harappan population. Few human figurines from Nousharo, Mehrgarh and Mohenjodaro represents common gender. A similar rite is still being performed by the present day Muslim population of Asia specially of south Asia.

Among the terracotta animal figurines bull is predominant. Bulls without humps from Mohenjodaro and Kalibangan, bulls with moveable heads from Mohenjodaro, climbing monkey and horse from Mohenjodaro and Lothal and unicorn from Chanhudaro, etc., are of special attraction.

Terracotta bird figurines like man holding the duck, mythical bird with wheel, bird in cage, peacocks and hens are of unique artistic value.

The seventh chapter is on ceramics. A few typical common shapes of Harappan ceramics are pointed bottom goblet, dish-on-stand, S shaped jar, perforated jar. The common archaeological denominator of Harappan pottery is wheel made monochromy black-on-red ware. The author have also described early Harappan pottery.

A selected bibliography of the Harappan civilization is appended at the end.

This book was edited by Dr. B.L. Nagarch ex-director excavation/exploration Archaeological Survey of India and author is grateful to him. The colour photographs used here were taken by Mr. J.C. Arora and black-and-white by Mr. Tejveer Singh.

I am also thankful to Anisha and Ekta, Raju, Arun Kumar Singh, Miss Neelam Singh and Mr. R.K. Bisht for typing the manuscript. I thank Mr. Sangam Jati, Amit Soni, Bhola, Saghun, Shikha and young boy Radhe Radhe for various types of help.

Discussion with S.P. Singh, J.P. Joshi, Prof. Anupa Pande, Vidula Jaiswal, B.L. Nagarch, Neru Misra, Rohini Pande, K.C. Nauriyal, K.K. Chakravarti, Vibha Tripathi, R.S. Bisht, R.R. Singh Chauhan, Nayanjyoti Lahiri, S.P. Gupta, Sharada Srinivasan and B.B. Lal and Lousie Martin of London added quite a bit to the author's knowledge and he is indebted to them. During 2001-02 author visited New York, Harvard and Boston Museum. During his stay, he studied excavated finds of Chanhudaro and other Harappan sites which are now in collection of Museums of U.S.A.

This script was prepared during 2003-2006 and the author has mostly used library of the National Museum, New Delhi Mrs. Pratibha Parasar head and Bhagwaniji Choubey, both members of the staff of National Museum library provided all important publications on Harappans. To all of them I am greatly indebted. The author also received help from the publications of B.B. Lal (1997), S.P. Gupta (1997), Catherine Jarrige (1988), Vidula Jayaswal (1989), R.S. Bisht (1999), J.P. Joshi (1994), Amrendranath (1999), Nayan Jyoti Lahiri (1995), During Casper, Kenoyer (1998), Vasant Shinde, Amy G. Postel, M.K. Dhawalikar and G.L. Possehl (2003), S.R. Rao, D.K. Chakrabarti, Bhuvan Vikram (2001), photographs are by the courtesy of National Museum and A.S.S. Sareen Ratnagar (2000 & 2001) and M.L. Nigam (2001). My wife Madhuri Sharma and my daughters Kadmbini and Devangana also helped me in preparation of script.

The author is greatly beholden to Ian Glover and Mark Newcomer, both professors who had been his teachers at the Institute of Archaeology London and taught him Archaeology during his stay in London in 1983-84 and Prof. G.R. Sharma, R.V. Joshi, V.D. Misra, J.P. Joshi, R.K. Varma, B.B. Lal, B.B. Misra, A.K. Sharma, V.N. Mishra, J.N. Pande, J.S. Negi, L.A. Narain, U.N. Roy, S.N. Roy, V.N.S. Yadav, Prof. G.C. Pande, Om Prakash, M.D. Khare, R.P. Tripathi, K.N. Dikshit, J.N. Pal, O.P. Srivastava and S.P. Gupta who had been my teacher in Allahabad, Delhi and Deccan College Poona.

The author is very much grateful to Mr. B.L. Bansal of M/s Sharada Publishing House for publishing this book within a short period.

Nomenclature

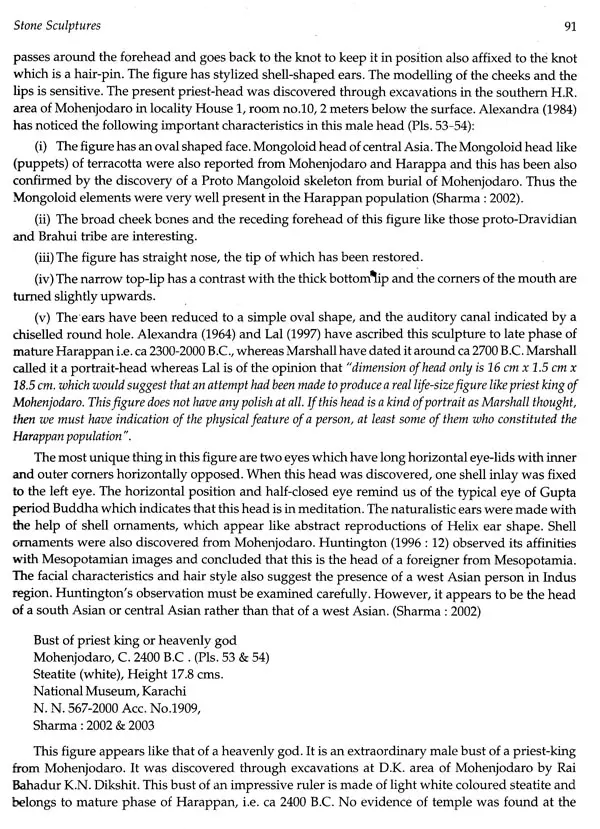

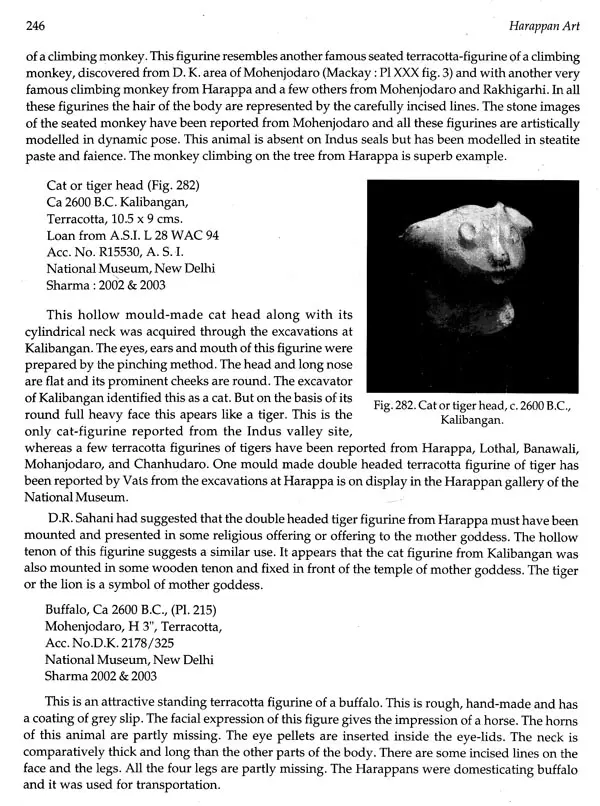

The Discovery of Indus civilization was first made during 1920-22 in the Indus Basin (Pl. 1). In the succeeding decades after 1922 a large number of sites were discovered in the Indus Valley and the archaeologist like D. K. Chakrabarti, Kenoyer and Possehl named this as lndus Civilization. This was due to the fact that the civilization was then limited to the Indus Valley proper region. Same archaeologists, like Nayan Jyoti and D.P.Sharma have called it Harappan Civilization named after Harappa, the first discovered site. Some South Asian archaeologists like S.P. Gupta and B.B. Lal have now come out with a new nomenclature as Indus-Sarasvati Civilization or Saraswati (Hakra) Civilization, because this civilization was not only limited in Sarasvati or Ghaggar (Hakra) region. Around 2668 Harappan and its related sites have been reported in south Asia. Around 1068 Harappan sites are located in Sarasvati region and 1600 sites are outside of Sarasvati region. The term Harappan Civilization is more appropriate (Map 1), Prof. Glover also call it south Asian Bronze Age Civilization.