The Indian Mother Goddess (Third Enlarged Edition)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAL380 |

| Author: | N. N. Bhattacharyya |

| Publisher: | Manohar Publishers and Distributors |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2023 |

| ISBN: | 8173043248 |

| Pages: | 378 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.0 inch x 6.0 inch |

| Weight | 650 gm |

Book Description

Encouraged by the reception the first edition received, the author expanded its scope and coverage and the second edition included the following chapters:

Introduction; The Mothers: Forms of the Cult; Mother Goddesses in Literary and Mythological Records; Mother Goddesses in Archaeology; and Mother Goddesses and the Advanced Religious Systems. In addition, there were three appendices, viz., Regional Distribution of the Goddess Cult; The Female-Dominated Societies; and Fertility Rites as the Basis of Tantricism. To further enrich the work two more appendices, viz., The Realm of Kamakhya, and Important Puranic Goddesses, along with an updated bibliography have been added in the present (Third) edition.

The study, a standard work on the subject, correlates the cult of Indian Mother Goddess with similar cults found in different parts of the world. It reveals interesting historical processes working behind the origin and development of the cult. It further highlights its popularity among the masses, specially among the lower order, its functional role in space and time and its entry into the so called higher forms of religious systems of India and abroad.

The study is marked by the author's accent on comparative treatment and on the social basis of religious ideas and deft handling of a bewildering variety of sources.

As an Indologist, Dr. N.N. Bhattacharyya requires no introduction. He is the author of such well-known works as The Indian Puberty Rites (1968, 1980), History of Cosmogonical ldeas (1971), History of the Sakta Religion (1978, 1996), History of Indian Erotic Literature (1975), Ancient Indian Rituals and their Social Contents (1975, 1996), Jaina Philosophy (1976, 1998), History of Researches on Indian Buddhism (1981 ), Buddhism in the History of Indian Ideas (1993), Indian Religious Historiography (1996), History of the Tantric Religion (1982, 1999), The Geographical Dictionary: Ancient and Early Medieval India (1991), and A Glossary of Indian Religious Terms and Concepts (1990,1999), etc.

He has edited R.P. Chanda's Indo- Aryan Races and N.C. Bandyopadhyay's Development of Indian Polity. He has also edited Medieval Bhakti Movements in India (1989), Jainism and Prakrit in Ancient and Medieval India (1994), and Encyclopaedia of Ancient Indian Culture (1998).

A retired professor of Calcutta University Dr. Bhattacharyya presided over the Ancient India section of the Indian History Congress in 1992.

The book was written in the 1960s and serialized in an historical journal, Indian Studies Past and Present, edited by the late Prof. Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya. Subsequently it came out as an independent treatise in 1970. The second edition with some alterations and additions came out from Manohar in 1977. Since the text in its present form appears to be complete in itself-evidently from the author's viewpoint despite shortcomings-no basic change has been made in its main body in this edition, but in order to make it more useful to the readers two extra appendices have been added-one on the Realm of Kamakhya and the other contains a list of important Puranic Goddesses. In addition, bibliography has been updated. It is at the behest of my esteemed friend Ramesh Jain of Manohar Publishers & Distributors that this new edition has been prepared. I thank him and Ajay for bringing out this book for the third time.

The present volume is a revised and enlarged version of my earlier work published in 1970. The cult of the Indian Mother Goddess has been reviewed here in a much wider historical perspective with greater details about its functional role in different religious systems. The first edition, despite many of it, shortcomings, earned a great deal of popularity. I shall consider my labour amply rewarded if the present edition also succeeds in meeting the needs of the readers.

I am extremely grateful to Dr. Mukhlesur Rahman, Director, Varendra Research Museum, Rujsahi University, Bangladesh, who has helped me by supplying a few valuable books from his personal collection. I must also thank Shri Ramesh C. Jain of Manohar Book Service without whose enthusiasm it would not have been possible for me to prepare the present edition.

Development Of The Conception

In primitive society the clan centred on the women, on whom the responsibility rested for the essentially important function of rearing the young and of imparting to them whatever could be characterized as the human heritage at the dawn of civilization. All cultural traits, including habits, norms of behaviours, inherited traditions, etc., were formed by and transmitted through the females. The woman was not only the symbol of generation, but the actual producer of life. Her organs and attributes were thought to be endowed with generative power, and so they were the life-giving symbols. In the earliest phases of social evolution, it was this maternity that held the field, the life-producing mother being the central figure of religion. This has been proved by the plentiful discovery of palaeolithic female figurines in bone, ivory, and stone with the maternal organs grossly exaggerated.

The following observations of Professor E.O. James, who made a thorough archaeological study of the cult of the Mother Goddess, are really significant for an historical understanding of our subject.

An adequate supply of offspring and food being a necessary condition of human existence, the promotion and conservation of life have a fundamental urge from palaeolithic times to the present day which has found magico-religious expression in a very deeply laid and highly developed cultus. Exactly when and where it arose is still very obscure, but it was from Western Asia, the South Russian plain and the valley of the Don that female figurines, commonly called 'Venuses', in bone, ivory, stone and bas-relief, often with maternal organs grossly exaggerated, were introduced into Western and Central Europe at the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic by an Asiatic migration in what is now known as the Gravettian culture, the former Upper Aurignacian .... With the transition from food-gathering to food-production the female principle continued to predominate the cultus that had grown up around the mysterious forces of birth and generation. Woman being the mother of the race, she was essentially the life-producer and in that capacity she played the essential role in the production of offspring. Nevertheless, as agriculture and herding became the established modes of maintaining the food-supply, the two poles of creative energy, the one female and receptive, the other male and begettive, could hardly fail to be recognized and given their respective symbolic significance. But although phallic emblems became increasingly prominent from Neolithic times onwards, the maternal principle, in due course personified as Mother Goddess, continued to assume the leading role in the cultus, especially in Western Asia, Crete and the Aegean, where the male god was subordinate to the Goddess. Essential in physiological fact as the conjunction of male and female is in the production of life, it would seem that at first there was some uncertainty about the significance of paternity. Therefore, as the precise function of the male partner in relation to conception and birth was less obvious, and probably less clearly understood, it is hardly surprising that he should be regarded as supplementary rather than as the vital agent in the process. Consequently, the mother and her maternal organs and attributes were the life-giving symbols par excellence.

These observations of Professor James may serve tentatively as the basis of our investigations. The material mode of life of a people ordinarily provides the rationale for the type of deity and the manner of worship prevalent in a given society. In a hunting society a special relationship generally develops between man and animal which leads its members to perform certain magical rites to secure prey in the next hunting expedition, or for other related ends. Their staple diet acquired a sacred character and significance. Relics of this primitive belief in the sacredness of the staple diet are found abundantly in the later sacrificial cults. Very probably these peoples grasped the generative function of women and sought magically to extend it to the animals and plants that nourished them. The Venus figures, of which we have already occasion to refer, had no faces, but their sexual characters were always emphasized. They were simply used in some sort of fertility ritual to ensure the multiplication of game.

The religious beliefs and practices of the food-gatherers were modified according to the new social ideals introduced by the Neolithic changes. Magic must have still been practised in order to ensure the fruitfulness of the earth, despite the enlarged real control over nature, thus introducing agricultural rituals in addition to those connected with hunting. The Upper Palaeolithic graves, in different parts of the world, were furnished with food, implements and ornaments; often the bones are found reddened with ochre. 'To paint bones with the ruddy colouring of life was the 'nearest thing to mummification which the palaeolithic peoples knew; it was an attempt to make the body again serviceable for its owner's use'. In Neolithic societies, the purpose of burial was changed. It was done with more pomp and social effort. The dead, so reverently deposited in the earth, was supposed somehow to affect the crops that sprang from the earth and was juxtaposed to the existing Mother Goddess cult, the Earth Mother thus becoming the guardian of the dead connected alike with the corpse and the seed corn beneath the earth." The Neolithic goddess was not simply the life-pro-ducing mother. The earth from whose bosom the grains sprout was imagined as a goddess who might be influenced like a woman by entreaties and gifts as well as controlled by imitative rites and incantations. Female figurines were moulded in clay or carved in stone or bone by Neolithic societies in Egypt, Syria, Iran, all round the Mediterranean and in South-Eastern Europe. These figurines were undoubtedly the direct ancestresses of the images of admitted goddesses made by historical societies in Mesopotamia, Syria, Greece and other countries.

The Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age of the archaeologists roughly corresponds to the food-gathering economy which provided the sole source of livelihood during the major period of the early history of mankind. The term 'Neolithic' is exceedingly difficult to define and determine, especially in the Indian context, since the transition from food-gathering to food production was not certainly a uniform and orderly sequence of events. The Neolithic cultures of India do not correspond to a fixed period of time, at least in the economic sense. Therefore, especially in the case of India, greater emphasis should be laid upon the anthropologicaI gradations which may be traced, identified and documented from the life of the surviving tribes and also from the literary records of the advanced peoples.

The surviving tribes of our times have been assigned by the anthropologists to three main categories-Hunting or Food gathering (two grades: the higher is distinguished from the lower by the use of bow and arrow); Pastoral (two grades:' in the higher grade, stock-raising is supplemented by agriculture) and Agricultural (three grades: first, garden tiIlage; second, field tiIlage and third, agriculture supplemented by stock-raising). The advanced pastoral and agricultural grades mark a stage of d is-integration in traditional tribal life which is caused by the production of surplus owing to the revolutionary changes in the technique of productions. These categories, however, are neither mutuaIly exclusive nor do they constitute a strict chronological sequence. Hunting and food-gathering are maintained, although with diminishing importance, throughout the pastoral and agricultural grades. The relation between stock-raising and tillage is largely determined by geographical, climatic and other factors.

We have already had occasion to refer to the nature of the cults and rituals of the food-gatherers or hunters. The pastoral tribes require greater courage and hardihood than the agricultural, and also an efficient leadership to protect the cattle. So the cults of heroes and ancestors attain their highest degree of development among the pastorals. The herder in his nomadic life has to live under the scorching heat of the sun, the dreadful thunders, the devastating storms. So his religion is mainly connected with the sky in which astral and nature myths, often personified in secondary gods and godlings, make their appearance. The Supreme Being of the pastoral religion is generally identified with the sky-god who rules over other deities like the headman of a patriarchal joint family. On the other hand, among the agricultural tribes, the cult of the Mother Earth, conceived as a female deity, is more prominent. Rituals based upon fertility magic must have played a very significant part in the agricultural societies.

So long as they have pasture, cattle feed and breed of them-selves, but by comparison with cattle-raising the work of tilling, sowing and reaping is slow, arduous and uncertain. It requires patience, foresight, faith. Accordingly, agricultural society is characterised by the extensive development of magic.

The magical rites designed to secure the fertility of the fields seemed to belong to the special competence of women who were the first cultivators of the soil and whose power of child-bearing had, in primitive thought, a sympathetic effect on the vegetative forces of the earth.

The fertility of the soil retained its immemorial association with the women who had been the tillers of the earth and were regarded as the depositaries of agricultural magic.

| Preface to the Third Edition | vii | |

| Preface to the Second Edition | ix | |

| Abbreviations | x | |

| Introduction | 1-34 | |

| Development of the Conception | 1 | |

| Mother Goddess and the Cults and Rituals of Fertility | 6 | |

| Mother Goddess and Agricultural Myths | 14 | |

| Mother Goddess and Female Dominated Societies | 23 | |

| The Mothers: Forms of the Cult | 35-82 | |

| Earth and Corn Mothers | 35 | |

| The Protectress of Children | 44 | |

| The City Goddesses | 48 | |

| The Goddess and the Animal World | 50 | |

| The Goddesses of Disease | 53 | |

| The War Goddesses | 57 | |

| The Goddesses of Mountains, Lakes and Rivers | 62 | |

| The Blood-thirsty Goddesses | 64 | |

| The Tribal Divinities | 67 | |

| Mother Goddesses in Literary and Mythological Records | 83-144 | |

| Prologue | 83 | |

| Goddesses of Egypt and Western Asia | 84 | |

| Goddesses of Greece and Asia Minor | 87 | |

| Goddesses of Mesopotamia and Iran | 92 | |

| Goddesses in the Vedic Literature of India | 94 | |

| Goddesses in the Epics | 101 | |

| Goddesses in Jain and Buddhist Literature | 109 | |

| Goddesses in South Indian Literature | 116 | |

| Goddesses in the Puranas | 119 | |

| Goddesses in other Literary Works | 126 | |

| Goddesses in Some Epigraphical Records | 132 | |

| Mother Goddesses in Archaeology | 145-193 | |

| The Earliest Archaeological Specimens | 145 | |

| The Harappan Goddess and Her Western Counterparts | 148 | |

| The Vedic and Post-Vedic Cults | 152 | |

| Specializations: The Gupta Age | 159 | |

| Mahisamardini and other Forms of Durga | 162 | |

| Uma, Parvati, etc. | 165 | |

| Laksmi and Sarasvati | 167 | |

| Matrkas, Yoginis, etc. | 171 | |

| Other Forms of the Goddess and their Shrines | 175 | |

| Buddhist and Jain Goddesses | 178 | |

| Mother Goddess and the Advanced Religious Systems | 194-232 | |

| Mother Goddess and Christianity | 194 | |

| Mother Goddess and Taoism | 201 | |

| Mother Goddess and Buddhism | 207 | |

| Mother Goddess and Vaisnavism | 214 | |

| Mother Goddess and Saivism | 218 | |

| Mother Goddess and Tantric Saktism | 222 | |

| Appendices | ||

| I | Regional Distribution of the Goddess Cult | 233-252 |

| The Epics and Puranas on Places Sacred to the Devi | 233 | |

| The Devi Shrines in Earlier Tantras and Puranas | 234 | |

| The 108 Holy Resorts of the Mother Goddess | 239 | |

| Some Important Sites and Toponyms | 241 | |

| The Sakta Pithas | 247 | |

| II | The Female- Dominated Societies | 253-277 |

| Economic Basis of the Social Domination of Sexes | 253 | |

| Anthropologists on the Concept of Mother-right | 254 | |

| Female-dominated Societies in Ancient Traditions | 258 | |

| The Women's Kingdoms in India | 261 | |

| Matriliny in Indian Societies | 262 | |

| Matrilocal Marriage in India | 265 | |

| The Philosophical Sankhya | 267 | |

| Two Important Views | 269 | |

| The Non- Vedic Current | 271 | |

| III | Fertility Rites as the Basis of Tantricism | 278-294 |

| Prologue: The Tantric Sex Rites | 278 | |

| Fertility Rites of the Vedic Age | 280 | |

| Rites de Passage | 283 | |

| Fertility and Funeral Rites | 286 | |

| The Ritual of Wine | 289 | |

| Female Principle in Rituals | 290 | |

| IV | The Realm of Kamakhya | 295-308 |

| V | A List of Important Puranic Goddesses | 309-326 |

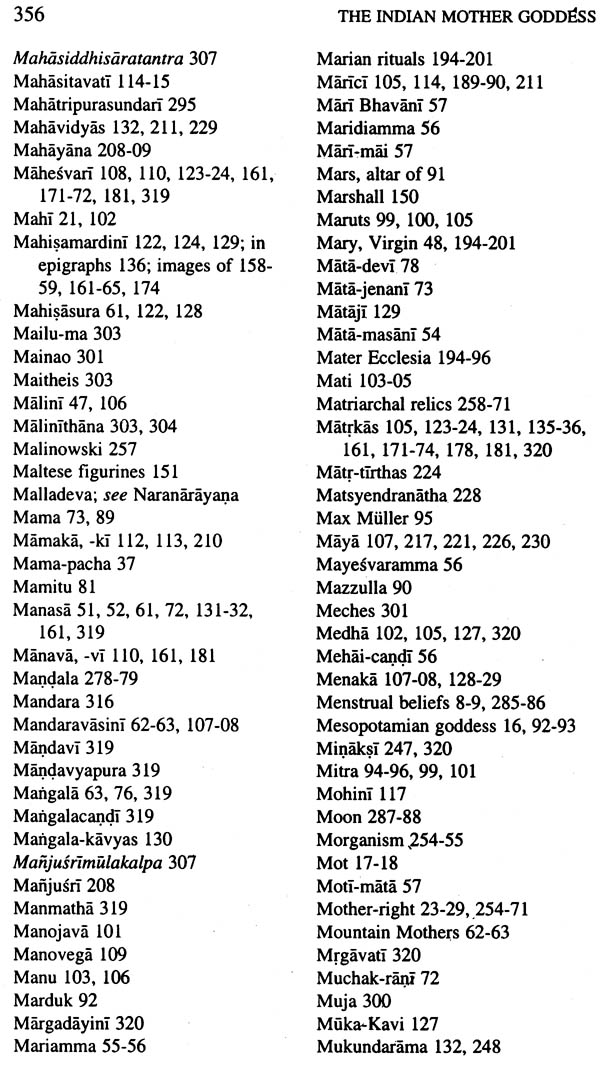

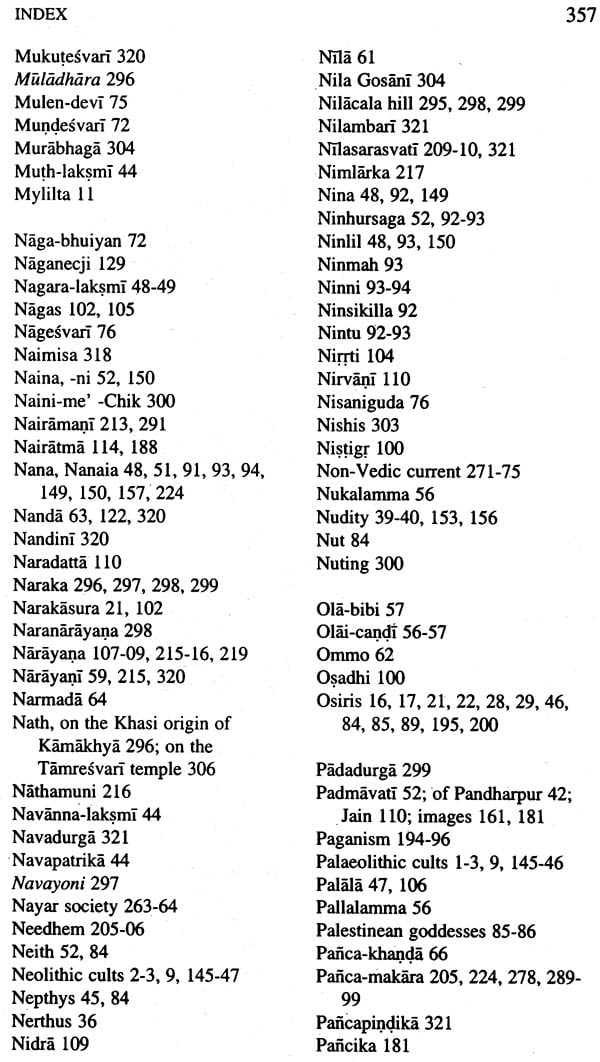

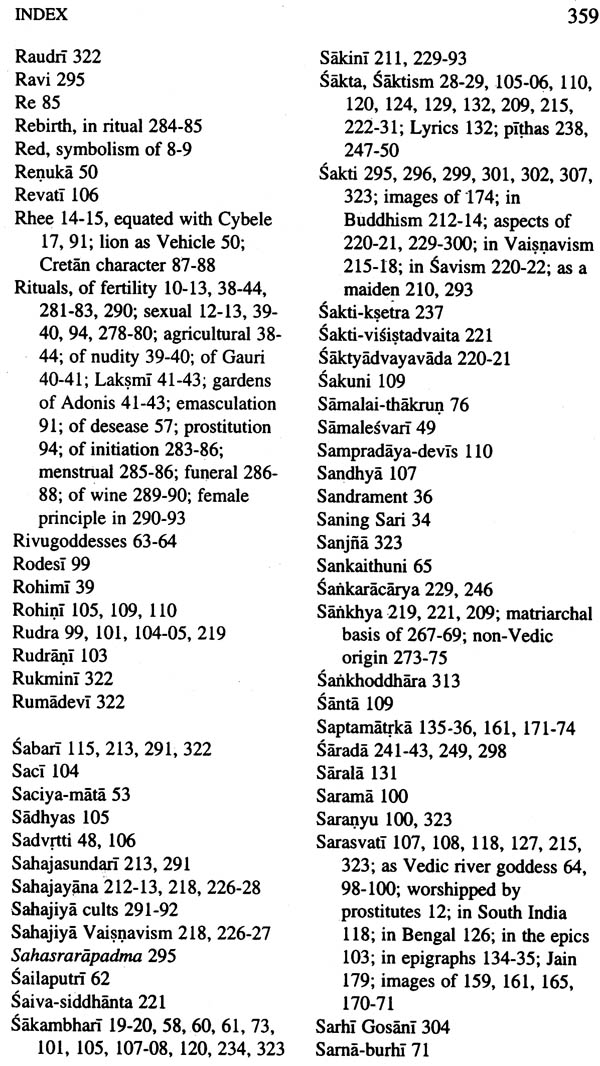

| Bibliography | 327-344 | |

| Index | 345-359 | |