Indo Tibetica (Set of 7 Books)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAN130 |

| Author: | Giuseppe Tucci Ed. Lokesh Chandra |

| Publisher: | Aditya Prakashan |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1988 |

| ISBN: | 8185179190 |

| Pages: | 1856 (5 Color and Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.5 inch X 6.5 inch |

| Weight | 4.70 kg |

Book Description

This set consists of the following 7 Books:

1. Stupa art, architectionic and symbolism.

2. Rin-chen-bzan-po and the renaissance of Buddhism in Tibet around the millenium.

3 (I). Temples of Western Tibet and their artistic symbolism: The monasteries of Spiti and Kunavar.

3 (II). Temples of Western Tibet and their artistic symbolism: Tsaparang.

4 (I). Gyantse and its monasteries. (General description of the temple)

4 (II). Gyantse and its monasteries. (Inscriptions)

4 (III). Gyantse and its monasteries. (Plates)

The present volume begins a series of studies which will be dedicated to the publication, investigation and elaboration of a vast archaeological, scriptural and literary material, collected during my long permanence in India and during my Tibetan expeditions. To this will be added the contribution of direct experiences which often are valuable in order to understand the meaning of a ritual, the ideal motif of an art work, the inner sense of a doctrine, in a much deeper way than that suggested by the simple .sequence of texts.

The title of this series indicates the fields of study which I intend, If not uniquely certainly especially, to turn my attention on: India and Tibet. For both of them, there is not only the question of geographical proximity, but rather of strict connection and cultural dependence. Except for minor Chinese influences and for rather large demonological survivals preceding the penetration of Buddhism, the Tibetan civilization and its creations may very well be considered as inspired by the great Indian experience specially by the Buddhistic. The Tibetan masters, both in solitary hermitages and in the immense and vastly populated convents, have maintained with wonderful fidelity the exegesis to the sacred texts; they have trod the ways traced by great Buddhist doctors in the famous universities of Nalanda, Vikramasila and Odantapuri, with conscience stricken operosity, and they have deepened the mystical experiences of the anchorites.

Upto our time, the attention of us orientalists has been engaged preferably in the investigation of historical and chronological problems. This work has been certainly useful, even necessary, but this should never let us lose sight of what should be the essential aim of our researches, namely the intimate understanding of the studied doctrines, rather than their juxtaposition in time.. This will partly explain the preference given to Chinese sources in the investigation on Buddhism. They give a lot of references and chronological data which would be lacking otherwise, and which have a great value especially when one thinks that they are concerned especially with die most glorious periods of Buddhism. But if we want to understand in all their values and meanings. those doctrines, maintained by the eloquent, but often inefficacious, dress of the word in the texts, and if we want to evaluate adequately their inner spiritual content, then, the Tibetan sources are of precious help to us. Certainly in Tibet there are many historical. and chronological works. They constitute invaluable documents for reconstructing the vicissitudes and the affiliations of the schools in the period of late Buddhism and in that of Lamaism .Moreover, they shed indirect light on one of the most obscure periods of Indian history. But the value of the immense Tibetan literature is of a much higher standard. An infinite cohort of exegctes belonging to all sects, from the Bka-dam-pa to the Dge-lugs-pa, from the Rnin-ma-pa to the Bkah-rgyud-pa, has commented upon, analysed, interpreted, clarified the enormous mass of Buddhist texts. Although this literature has scarce originality, because it follows Indian traditions, nevertheless it has subtlety and depth. It is, in any case, of great help not only to comprehend in a philological way the doctrinal and mystical treatises, but specially to get their actual meaning in order to translate them in our terms, so that we may have an adequate idea of the described experiences which have dominated and directed the spiritual life of great men both in India and in Tibet.

It will shed light for a better understanding of Buddhism, and therefore--since all manifestations of Indian theosophical thought are intimately connected and since the religion of the Buddha has greatly influenced the whole of the East-we shall prepare ourselves to understand deeper and better the Indian soul and the stern in general. This world by now should no longer interest us merely as a vast field for philological exercises, it is a world which lives an intense and multiform life of its own and which is called by the historical vicissitudes of our times to enter into a eater and more direct collaboration with us.

The complexity and the vastness of such a research will not low perhaps great works of synthesis as yet. Besides, there are still many difficulties in this, as for instance the many literatures which one needs to master fairly well and the difficulties to consult all the literary and archaeological sources. Moreover, there are many connections between civilizations and experiences which we do not know as yet, because, although such civilizations and experiences apparently seem to be quite apart from one another, nevertheless they have been linked by hidden and unforeseen currents. Therefore, we can .conduct special researches as complete

possible only on particular problems, and the synthesis of such aspects of the life, thought and art of eastern peoples which, we can manage to achieve with some possibilities of success through the present state of our knowledge.

Only in this way we can shed definitive light on many dark points which are still obscure in the history of oriental civilization.

As a general rule we quote the documentation in appendix, Id we will always translate the texts we use. In this manner the non-specialist as well can follow our researches. This will certainly be a useful thing to our culture in a moment in which stances are disappearing, people coming nearer and trying to understand one another, and the renewing spirit wants to understand all experience and tries again all ways.

Contents

| Introduction | v-xxxv | |

| Preface | 7 | |

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| 1 | Tibetan literature about the stupa (Mchod-rten) | 13 |

| 2 | Its Connections with the Indian architectonic literature | 18 |

| 3 | The supposed Indian patterns of the eight types of stupa (mchod-rten) | 21 |

| 4 | Why the Stupas (mchod-rten) are built | 24 |

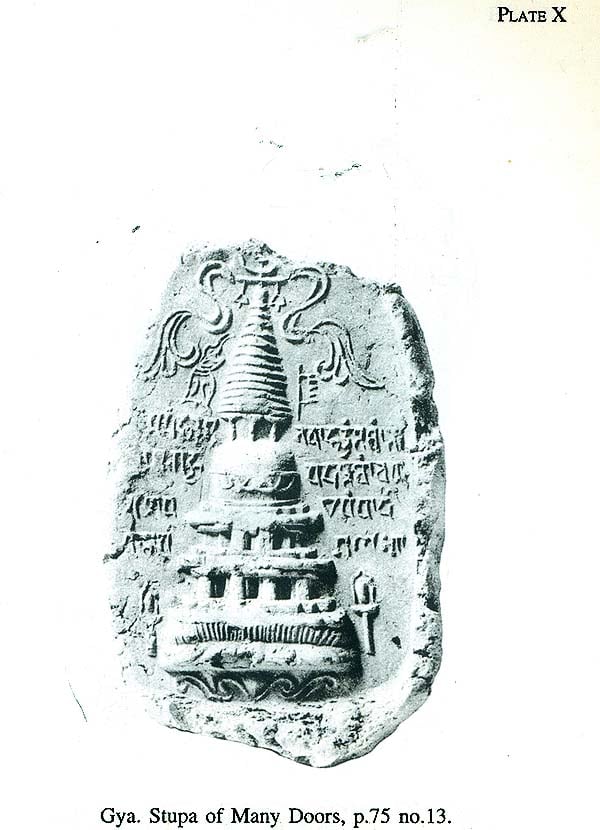

| 5 | The Stupa (mchod-rten) engraved or in miniature | 32 |

| 6 | Ritual for the building of a stupa (mchod-rten) | 34 |

| 7 | The Stupa (mchod-rten)as repositiory of sacred things | 38 |

| 8 | Symbolism attributed to the stupa (mchod-rten) according to hinayana and Mahayana | 39 |

| 9 | Diffusion of the various types of stupas Imchod-rten) in Indian and eastern Tibet | 51 |

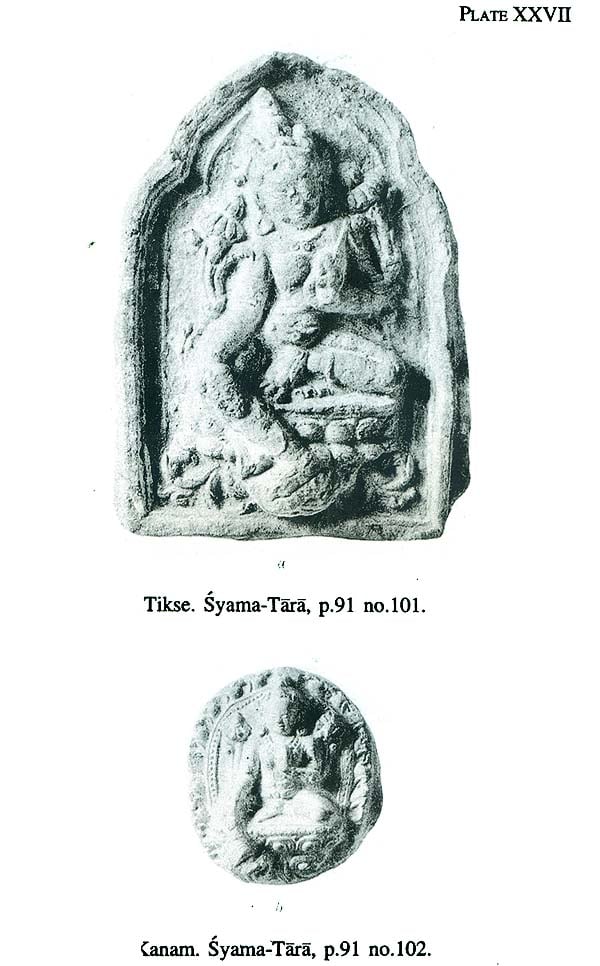

| 10 | What is the meaning of tsha-tsha | 53 |

| 11 | Origin and meaning of tsha-tsha | 55 |

| 12 | Ceremonial for the preparation of the tsha-tsha | 57 |

| 13 | Various types of tsha-tsha and their chronological order | 60 |

| 14 | Iconographic types represented on the tsha-tsha | 62 |

| | ||

| | ||

| Collection in Ladakh, Spiti, Kunuvar, Guge | ||

| I | Group of signillary impressions | 73 |

| (a) Impressed with figures (s) of a stupa (mchod-rten) | ||

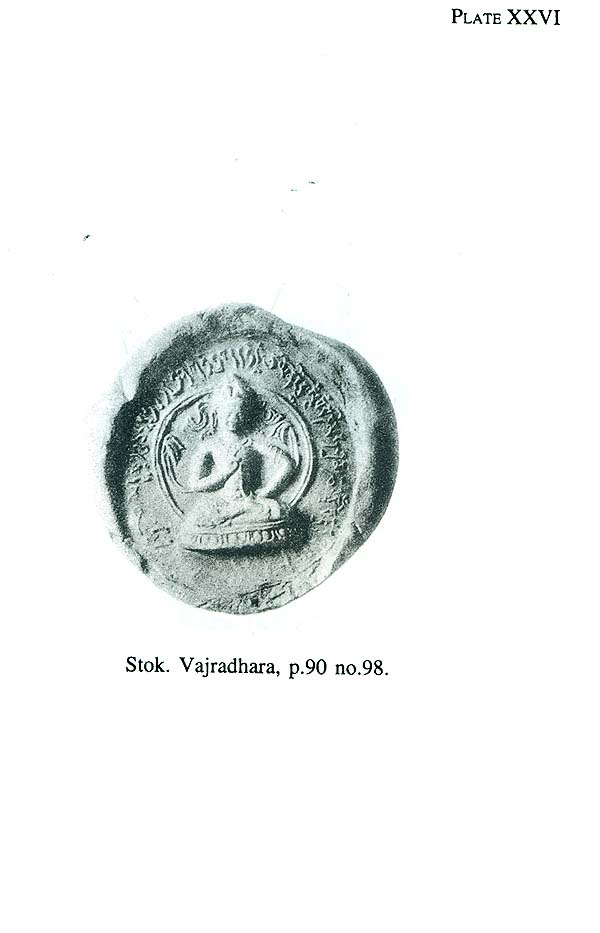

| (b) with figures of divinities | ||

| II | Group of the stamped | 79 |

| (a) Simple divinities | ||

| (b) Grouped Divinities | 99 | |

| (c) Guru and siddha | 102 | |

| III | In the shape of stupa (mchod-rten) | 106 |

| IV | Bon-po tsha-tsha | 108 |

| Appendices | ||

| I | The Tibetan texts on Stupa (mchod-rten) | |

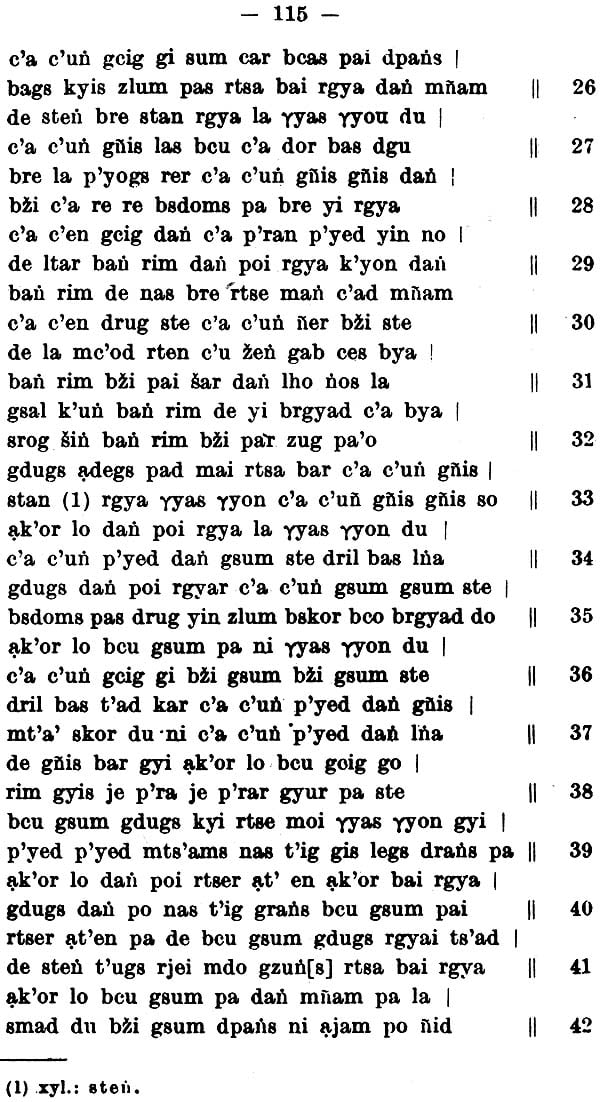

| First Text | 113 | |

| Second text | 118 | |

| Translation of the first Text | 121 | |

| Translation of the second text | 127 | |

| II | The fight between Vajrapani and Mahadeva | |

| Text | 135 | |

| Translation | 140 | |

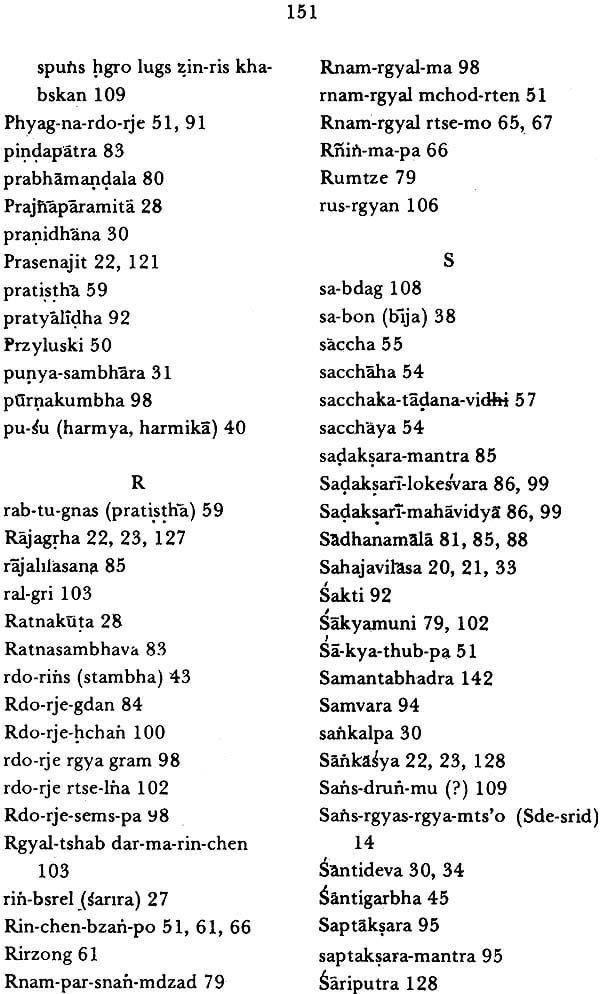

| Index | 147 |

Vol-II

Rin-chen-bzan-po is the key figure in the Later Spread of Dharma after its persecution by Glan-dar-ma in A.D. 901. Due to him it first appeared. in Mnah-ris and later on spread to Dbus and Gtsan. He is famous for his translations of both the sutras and tantras, and extensive explanations of the Prajnaparamita, The Blue Annals says: "The later spread of the Tantras in Tibet was greater than the early spread, and this was chiefly due to this translator (lo-tsa-ba). He attended on seventy-five panditas, and heard from them the exposition of numerous treatises on the Doctrine. Lha-chen-po Lha-lde-btsan bestowed on him the dignity of Chief Priest (dbuhi mchod-gnas) and of Vajracarya (rdo-rje slob-dpon). He was presented with the estate of Zer in Spu-hrans, and built temples. He erected many temples and shrines at Khra-tsa, Ron and other localities, as well as numerous stupas. He had many learned disciples, such as Gur-sin Brtson- grus-rgyal-mtshan and other, as well as more than ten translators who were able to correct translations (zus-chen pher-bahi lo-tsa-ba). Others could not compete with him in his daily work, such as the erection of images and translation of (sacred texts), etc. He paid for the recital of the Nama-sangiti a hundred thousand times in the Sanskrit language, and a hundred thousand times in Tibetan, and made others recite it a hundred thousand times". (Blue Annals 68-69).

"This Great Translator on three occasions journeyed to Kasmira, and there attended on many teachers. He also invited many panditas to Tibet and properly established the custom of preaching (the Yoga Tantras). (Blue Annals 352). In Tibet the system of Jfianapada was first introduced by the Great Translator Rin-chen-bzan-po. The latter preached it to his disciples and it was handed down through their lineage (Blue Annals 372). The widely propagated teaching and manuals of meditation (sgrub-yig) according to the initiation and Tantra of Sri-Samvara, originated first in the spiritual lineage of the disciples of the Great Translator Rin-chen-bzan-po (Blue Annals 380).

"At that time the lo-tsa-ba Rin-chen-bzan-po thought: 'His knowledge as a scholar is hardly greater than mine, but since he has been invited by Lha-bla-ma, it will be necessary (for me) to attend on him.' He accordingly invited him to his own residence at the vihara of Mtho-ldin, (In the vihara) the deities of the higher and lower Tantras were represented according to their respective degrees and for each of them the Master composed a laudatory verse. When the Master sat down on the mat, the 10- tsa-ba (Rin-chen-bzan-po) inquired from him: 'Who composed- these verses?'-'These verses were composed by myself this very instant' replied the Master, and the lo-tsa-ba was filled with awe and amazement. The Master then said to the lo-tsa-ba: 'What sort of doctrine do you know?' The lo-tsa-ba told him in brief about his knowledge and the Master said: 'If there are men such as you in Tibet, then there was no need of my coming to Tibet!' Saying so, he joined the palms of his hands in front of his chest in devotion. Again the Master asked the lo-tsa-ba '0 great lotsa- ba when an individual is to practise all the teachings of Tantras sitting on a single mat, how is he to act?' The lo-tsa-ba replied: 'Indeed, one should practise according to each (Tantra) separately.' The Master exclaimed: 'Rotten is the lo-tsa-ba! Indeed there was need of my coming to Tibet! All these Tantras should be practised together.' The Master taught him the 'Magic Mirror of the Vajrayana' (Gsan-snags-hphrul-gyi me-Ion), and a great faith was born in the lo-tsa-ba, and he thought: 'This Master is the greatest among-the great scholars!' He requested the Master to correct (his) previous translations ....

"The Master said: 'I am going to Central Tibet (Dbus), you should accompany me as interpreter. At that time the great 10- tsa-ba was in his 85th year, and taking off his hat, he said to the Master (pointing out to his white hair): 'My head has gone thus, I am unable to render service'. It is said that the great lo-tsa-ba had sixty learned teachers, besides the Master, but these others failed to make the lo-tsa-ba meditate. The Master said: '0 great lo-tsa-bal The sufferings of this phenomenal world are difficult to bear. One should labour for the benefit of all living beings. Now, pray practise meditation!' The lo-tsa-ba listened attentively to these words, and erected a house with three doors, over the outer door he wrote the following words: 'Within this door, should a thought of attachment to this Phenomenal World arise even for one-single moment only, may the Guardians of the Doctrine split (my) head!' Over the middle door (he wrote): 'Should a thought of self-interest arise even for one single moment only, may the Guardians of the Doctrine split (my) head.' Over the inner door (he wrote): 'Should an ordinary thought arise even for one single moment only, may the Guardians of the Doctrine split (my) head' (The first inscription corresponds to the stage of Theravada, the second to that of the Bodhisattva-yana, and the third to the Tantrayana). After the departure of the Master, he practised 'one-pointed' (ekagra) meditation for ten years and had a vision of the mandala of Sri-Samvara. He passed away at the age of 91". (Blue Annals 249-250).

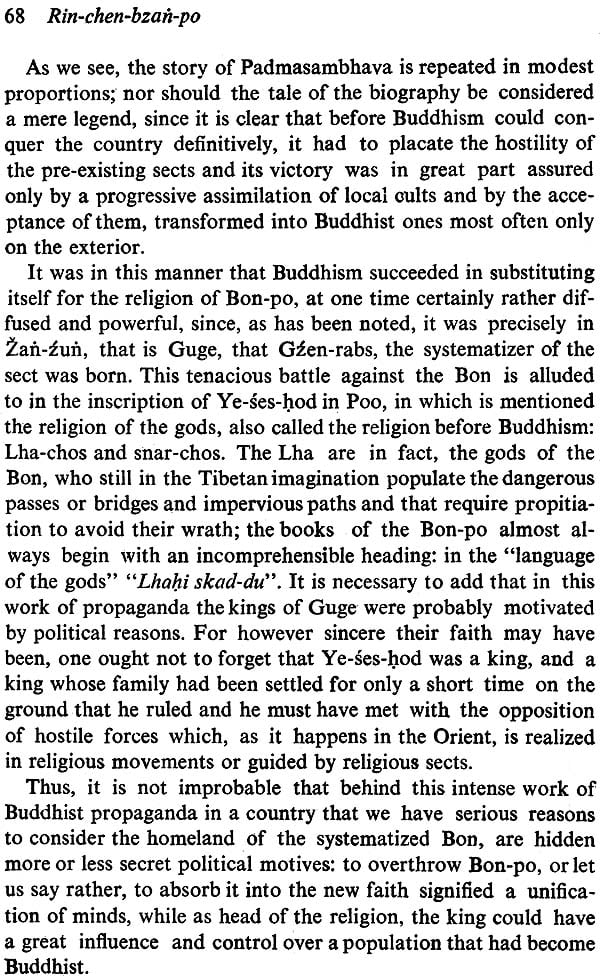

While Buddhism spread anew with greater purity and its under- standing deepened by the new/sirtras and tantras, Rin-chen-bzan- po realised that the translations of sacred texts alone would not do, and to irradiate the faith temples would have to be built.and would also have to be attractive to draw people. He brought with him artists and craftsmen from Kashmir to embellish temples newly built all over the country. The temples at Tsaparang, tholing, Tabo and elsewhere in Western Tibet bear clear evidence of the craftsmanship of Kashmiri masters. The murals of Mail- nail temple are the only surviving frescoes of the Kashmiri idiom known today. There is a sharp distinction between the school of Guge and the school of Central Tibet, in spite of the same spiritual world. While Guge leaned on Kashmir because of geographic proximity, Central Tibetan schools were influenced by the Pala and Nepalese idiom (Tucci 1949:1.272-215).

Contents

| 1 | Preface: Lokesh Chandra | 1 |

| 2 | Historic background | 5 |

| 3 | The Importance of Rin-chen-bzan-po as lotsava | 7 |

| 4 | Rin-chen-bzan-po of Buddhism at the time of Rin-chen-bzan-po | 12 |

| 5 | The dynasties of Western Tibet as patrons of Buddhism | 14 |

| 6 | The School assembled around Rin-chen-bzan-po | 25 |

| 7 | The sources concerning Rin-chen-bzan-po and their historic value | 27 |

| 8 | Rin-chen-bzan-po and his school according to the Deb-their | 28 |

| 9 | Rin-chen-bzan-po and his school according to Pad-ma-dkar-po | 33 |

| 10 | Religious exchange between Tibet and India | 37 |

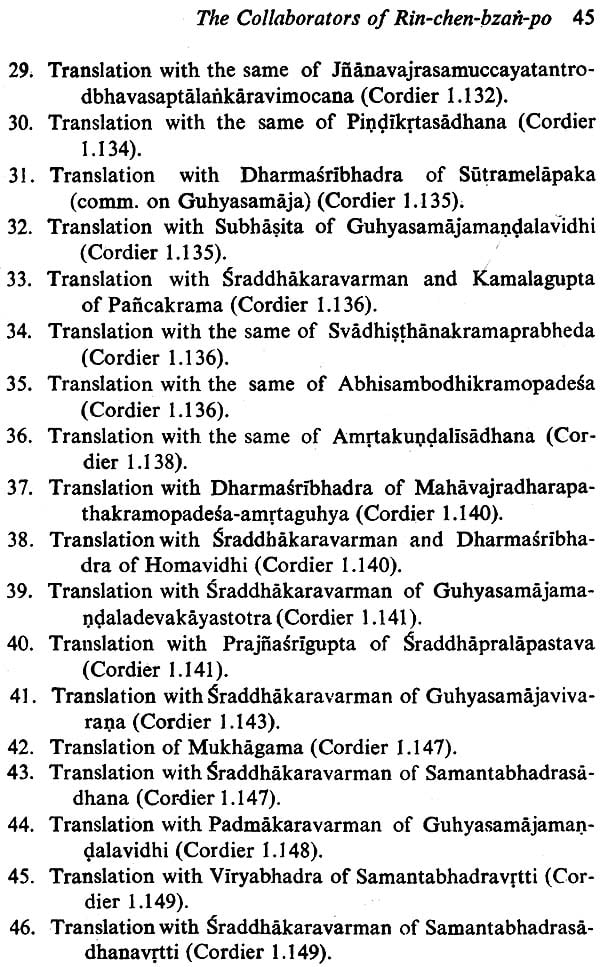

| 11 | The collaborators of Rin-chen-bzan and their translations | 39 |

| 12 | Synchromisms between translations and translators | 49 |

| 13 | The rnam-that of Rin-chen-bzan-po | 53 |

| 14 | Travel to India and the Itinerary that he followed | 58 |

| 15 | Construction of the three principal temples | 62 |

| 16 | Another trip to india | 66 |

| 17 | New activities of Rin-chen-bzan-po | 67 |

| 18 | Work of art and books depositied in the temples | 69 |

| 19 | Other religious foundations attributed of Rin-chem-bzan-po | 71 |

| Appendix | 75 | |

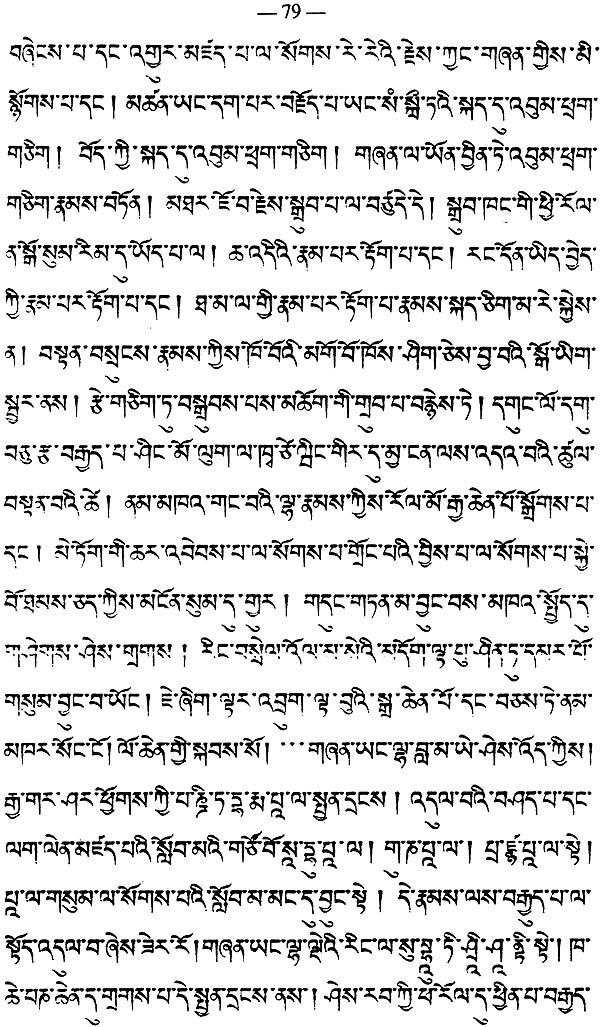

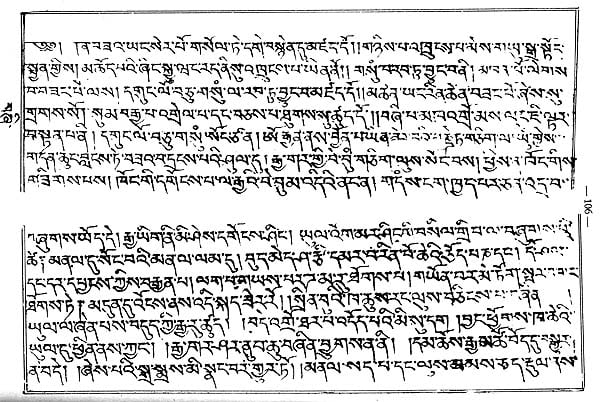

| Tibetan passages | 77 | |

| Indexes | 91 | |

| I | Cited Sources | |

| a | Tibetan sources | 93 |

| b | European sources | 95 |

| II | Index | 96 |

| Tibetan text of the biography of Rin-chen-bzan-po Map at the end | 103 |

Vol-III

Part-I

Back of the Book

Fundamental studies on Tibetology are incorporated in the four volumes (seven bindings) of Professor Giuseppe Tucci' s Indo- Tibetica. As the work appeared in Italian, very few scholars have benefited by the' crucial results of Tucci' s investigations and perceptions. Moreover, Indologists hardly ever approached it, as Tucci used Tibetan terms like mchod-rten for stupa. The presented English version of the Indo- Tibetica will place at the disposal of Indologists, Tibetologists, Buddhologists, Historians, Anthropologists, Archaeologists and specialists in allied areas and disciplines, a basic work which presents new material from unpublished sources and unexplored monasteries on the frontiers of India and in bordering areas. Sanskrit equivalents of Tibetan terms have been used throughout to make the text accessible to a wider audience, for example, stupa (mchod-rten).

This volume describes the ancient monasteries of Spiti and Kunavar, namely, those at Tabo, Lhalung, Chang and Nako. Prof. Tucci has identified the paintings of mandal as and individual deities in the temples and elucidated their symbolism at length. The abundance of mystic meanings of the deities and cycles represented is interpreted from Sanskrit and Tibetan texts. The first chapter details the main temple of the monastic complex of Tabo, dedicated to the Vajradhatu mandala, The second describes the Gserkhan or Golden Temple of Tabo. Its walls are covered with ancient frescoes that go back to the 16th century. The Dkyil-khan or Mandala Temple constitutes the third chapter. Its paintings are from the 17th century. Chapter IV is devoted to the minor temples at Tabo. The next three chapters V, VI and VII take up the temples at Lhalung, at Chang, and at Nako. The Nako temple has frescoes of the 14-15 century.

This volume is of unique importance to understand the fundamentals of Vajrayana art as a concomitant of mysteriosophic realisation. Prof. Tucci has propounded the symbolic and esoteric meaning of the mandalas at length, and in depth which is unique to him. Two Kahsmiri wooden sculptures of 10-11 th century in the Tabo Gtsug-lag-khanare valuable for the history of Indian art.

A detailed preface by Lokesh Chandra throws further light on the mandalas of Vairocana, which dominate the temples in this volume. He clarifies the various types of these mandalas which had posed problems of Tucci. The murals of Nor-bzan had escaped identification by Tucci, but have now been concorded to Sudhana of the Gandavyuha. The role of photism in the evolution or Tantras is discussed.

This work calls for further field exploration and table research, on the extant sutras and chronicles, and on the murals and sculptures in the ancient territories of Guge.

Prof. GIUSEPPE TUCCI (1894-1984) is the doyen of modern scientific studies of Tibetan arts and thought, history and literature. He was for many years Professor of Religions and philosophies of India and the Far East at the University of Rome. He also taught at universities in India. Professor Tucci made several visits to Nepal and has been on eight expeditions to Western and Central Tibet, collecting historical, artistic and literary material. His scientific expeditions resulted in many historical books, like the Tibetan Painted Scrolls and the seven volumes of Indo- Tibetica in Italian. Prof. Tucci gives word to the mute dialogue of the mind with the mysterious presences in the Land of Snows.

The General Editor of the series of Prof. LOKESH CHANDRA who is a renowned scholar of Tibetan, Mongolian and Sino- Jananese Buddhism. He has to his credit over 360 works and text editions. Among them are classics like his Tibetan-Sanskrit Dictionary, Materials for a History of Tibetan Literature, Buddhist Iconography of Tibet, and his ongoing Dictionary of Buddhist Art in about 20 Volumes. Prof. Lokesh Chandra was nominated by the President of the Republic of India to the Parliament in 1974-80 and again in 1980-86. He has been a Vice- President of the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, Chairman of the Indian Council of Historical Research Presently: Director, International Academy of Indian Culture.

This volume III.I of the Indo-Tibetica describes the ancient monasteries of Spiti and Kunavar, namely, those at Tabo, Lhalung, Chang and Nako. Prof. Tucci has identified the paintings of mandalas and individual deities in the temples and elucidated their symbolism at length. Usually he names the iconography of the central wall, then of the left wall and finally of the right wall. At times this scheme has to be discovered in the rich wealth of detail, and the bountiful abundance of mystic meanings of the deities and cycles represented. The introduction gives a synoptic view of the monastic centres in a threadbare clarity that can lead the reader to the overflowing poesy of Tucci's interpretation.

The monastic complex at Tabo has eight temples enclosed by a boundary wall (p.24). Among them, three temples are important from the artistic and historical standpoint:

Central temple or Gtsug-Iag-khari Golden temple or Gser-khari Mandala temple or Dkyil-khan.

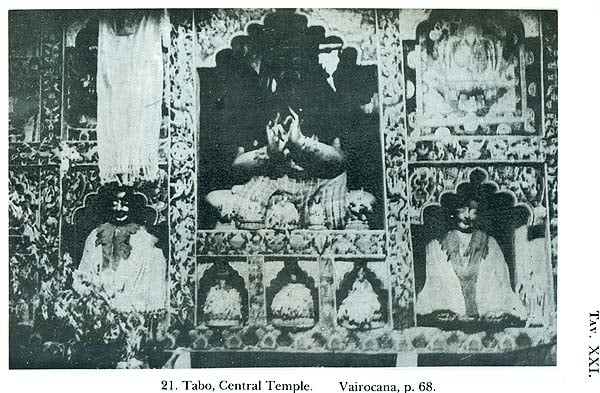

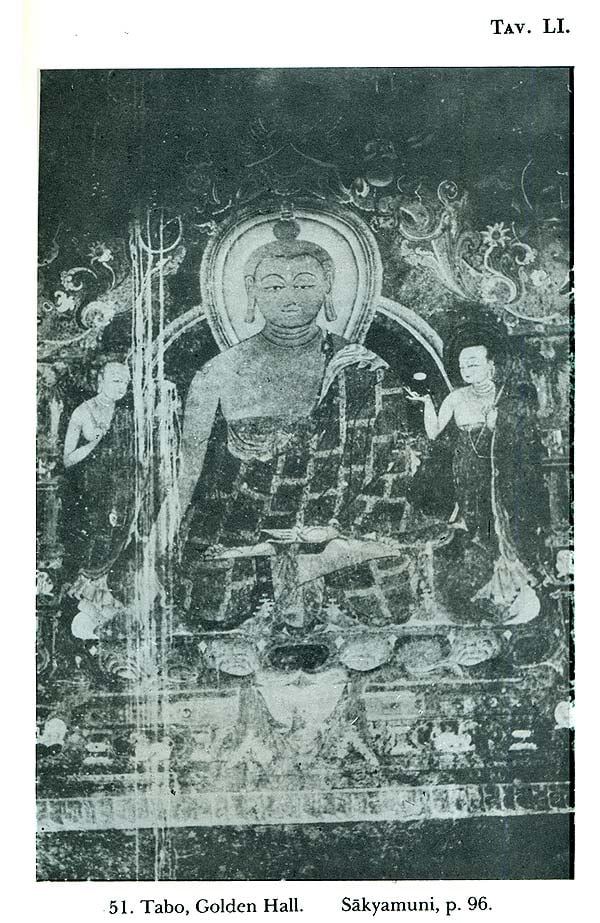

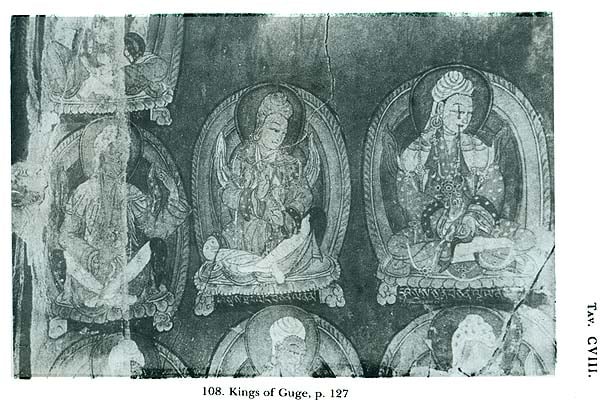

The Gtsug-lag-khan has the Vajradhatu-mandala of Vairocana, as was the preference for mandalas of Vairocana in the school of Rin-chen-bzan-po. Life-size stucco images of deities of the mandala are set around the walls, with a central fourfold image of Vairocana. Beneath the stucco statues are the frescos of the life of Sakyamuni on the right wall and on the left wall of the pilgrimage of Sudhana which is dealt with at length in the Gandavyuha, a surra of the Avatamisaka school.

Beyond the fourfold image of Vairocana and the stucco images of the Vajradhatu-mandala, at the far end we enter a cella. The central statue in the cella is that of Amitabha (p.78). Tucci brings in the Five Buddhas. Here Amitabha is on his own and does not belong to the quinary system of the Five Buddhas. He is surrounded by four acolytes: Avalokita, Mahasthama-prapta, Ksitigarbha and Akasagarbha. There is a parallel to this scheme at the Horyuji monastery in Japan.

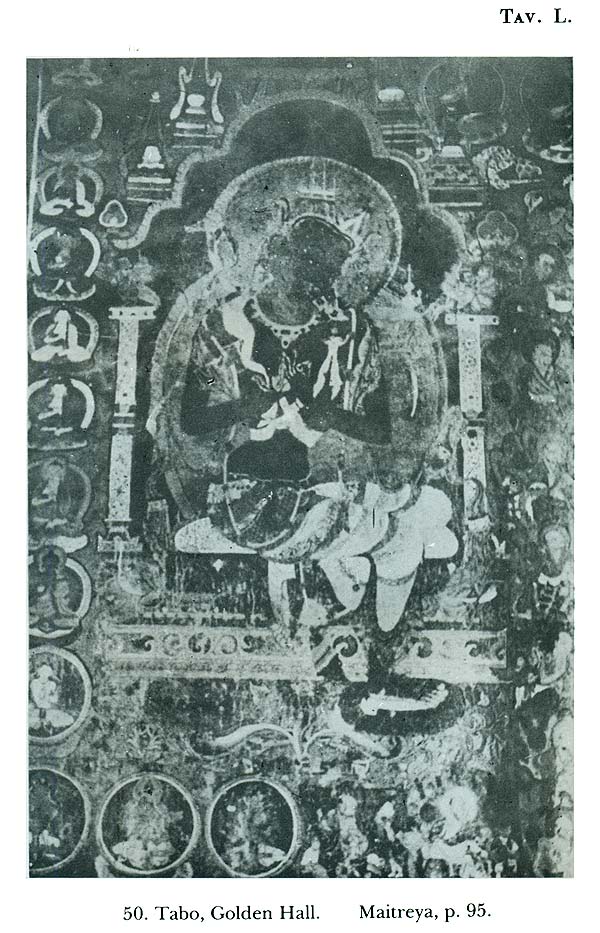

Chapter II describes the Gser-khari or Golden Temple of Tabo. The walls are covered with ancient frescos that go back to the 16th century. The depictions on the walls are as follows: Left wall: a) Bhaisajyaguru, b) Amitabha flanked by Avalokita and Mahasthamaprapta, c) Vajradhara.

Central wall: a) Maitreya, b) Sakyamuni surrounded by Sixteen Arhats, c) Manjusri.

Right wall: a) Sarvavid Vairocana encircled by the Thirtyseven Deities in medallions, b) Green Tara, c) Vijaya.

Chapter III takes up the Dkyil-khan or Mandala Temple. It has been modernised. The paintings pertain to the 17th century. It was used for invitiation rites/abhiseka. The central figure is of Sarvavid Vairocana surrounded by deities in medallions. On the left wall is a mandala of Aksobhya. The right wall has a mandala whose central' deity is erased. This temple has paintings of a historical character. To the left of the door are paintings of Byan-chub-hod, Zhi-ba-hod and Ye-ses-hod. The panoramic view of the monasteries of Tholing and Tabo is painted on the right of the central wall and also bears an inscription.

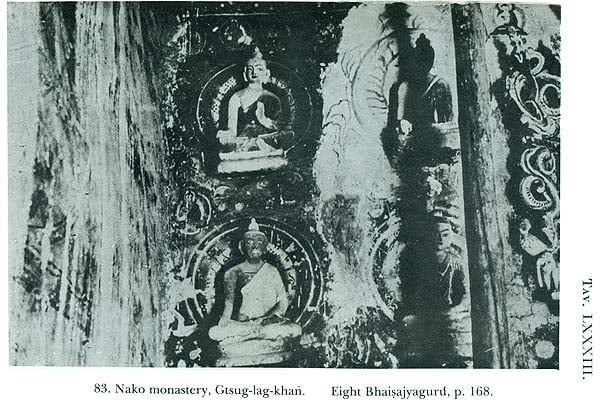

Chapter IV is devoted to the minor temples at Tabo. Among them, the Byams-pa lha-khari "Maitreya temple" has a recent statue of Maitreya. The smaller Hbrom-ston temple has an ancient door of deodar wood of the 12th century. The larger Hbrom-ston temple is empty. It has paintings of the eight Bhaisajyaguru going back to the 17th century. The Lha-khan dkar-byun is insignificant.

Chapter V describes the temple at Lhalung. The left wall has a mandala of eight-armed Vairocana attended by sixteen deities (four Tathagatas and twelve goddesses). The central wall has Vagisvara Manjusri with four attendant deities to the left, and Maitreya with his parivara of four deities to the right. The right wall shows Prajnaparamita.

Chapter VI takes up the Temple of Chang in Upper Kunavar. The central wall has a big figure of Sakyamuni, with deities of the Naraka mandala all around. Two small frescos to the left of the door may be connected with the foundation of the temple.

Chapter VII describes the monastery at Nako with four small temples enclosed by a boundary wall. Temple no. 1 is recent. Temple no. 2 has stucco images of the Parica-tathagata. Tucci gives the mystical meaning of the pentad at length. On the left wall is Prajnaparamita and on the right wall is the mandala of Sarvavid Vairocana. The central figure of Temple no. 3 is Yellow Tara with the images of Eight Bhaisajyaguru on the sides. The mandala on the left wall has disappeared. The right wall has the mandala of Vairocana. Besides the monastic complex, Nako has a temple of Padmasambhava. It had paintings of the 14-15th century, of whom only four are better preserved on the left wall, faint traces of a mandala can be seen on the central wall, and the right wall has Amitayus, Sakyamuni and Amitabha.

This volume is of unique importance to understand the fundamentals of Vajrayana art as a concomitant of mysteriosophic realisation. Prof. Tucci has propounded the symbolic and esoteric meaning of the mandala, or cycle as he terms it, not only at length, but in depth which is unique to him and inimitable. In the depth of visualisation the individual becomes a dynamited centre. As a new centrum, he envisions and creates, leading to new concatenations, to new mandalas. The broad outlines remain, but new cycles emerge. Their manifestation is art, which baffles scholars who seek uniform systems. Naturally, symbolism dominates this perceptive work of Tucci. It imparts a living dimension to ancient statues in the round and to the two-dimensional frescos on the walls of monasteries.

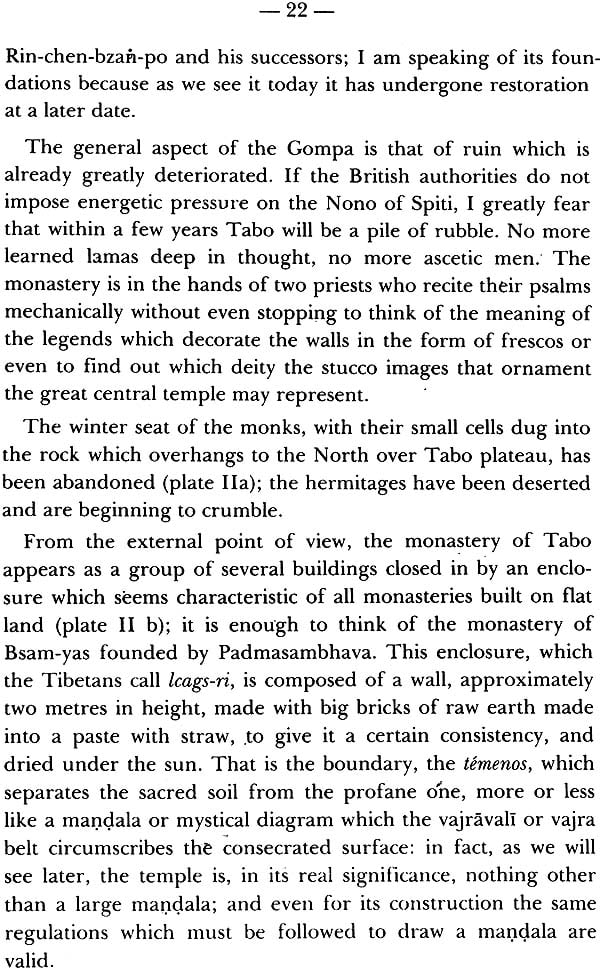

§ 1. The Historical Geography of Western Tibet. In the second volume of Indo- Tibetica, specially devoted to Rin-chen-bzari-po (1), I believe I have thrown some light on the importance of the work developed around the year 1000 by this great missionary and apostle of Buddhism in Western Tibet and also to have established the role which in the Renaissance of Lamaism, is verified during that period of time in the Land of Snows, in the province of Guge and its kings. I have also shown that Rin- chen-bzan-po was not only a great translator who introduced new texts of dogma and mysticism into Tibet and a master of spiritual experience until then unknown to the inhabitants of his land, but also that he wants to be remembered as one of the most tireless builders of temples and sacred buildings that Tibet has ever known. His name will remain forever connected to one of the most important periods in the history of Tibetan art.

His biography and other Tibetan historical works have preserved for us the list of monuments erected by his extremely noble figure of the newly-born Lamaism; but, as I said in the aforementioned volume, it was difficult, with our extremely scarce geographical knowledge of Western Tibet, to identify exactly every place which tradition connected in some way with Rin-chen-bzari-po and in which at one time an intellectual, religious and artistic life of such quality took place, in a region which has been today almost completely abandoned. It was necessary to go to the place, to inspect the site, to collect first-hand information from people, to verify my previous identifications and above all to explore the region archaeologically, to collect the artistic material, manuscript, iconographic and epigraphic material of the period and to visit one by one the temples attributed to Rin-chen-bzari-po and erected by the Guge kings and to see how much light these and the documents preserved there could still throw on the great activity of thought and art which during the time of Ye-ses-hod and his successors developed in the Himalayas between Spiti and the Manasarovar lake. It was in fact with this purpose that the Accademia d'Italia entrusted to me, under the high patronage of the Duce, the command of a new expedition into Western Tibet, to the success of this the enlightened interest of the British authority in India also contributed, since they well understood the importance of my trip and were generous with their assistance and, for a start, managed to obtain for me the permit to cross the Tibetan frontier, a privilege, as is well-known, granted to very few.

In this manner I managed not only to verify the purely literary data preserved in these historical and biographical •works, but to collect a vast amount of material which I will be publishing and illustrating regularly in this series. This is not only of interest to the political, religious and artistic history of Guge, but contributes to a better and more precise knowledge

of Lamaism and of its many aspects which are even now partially unkown. But all this has been said in the report on the trip already published by the Reale Accademia- d'Italia (Royal Academy of Italy) and I ask those who are interested in further details about the itinerary followed and the happenings during our expedition to consult it.

I should rather re-start the study of the list of temples attributed to Rin-chen-bzari-po published by me in Volume 11 of Indo-Tibetica. The first thing that I have been able to establish is that a geographical identification of many of them must be correct; many places, connected by means of oral and literary tradition with the great apostle, are completely unknown to Europeans and are not marked on the map, not even in that of the Survey which are doubtlessly the best. And in fact on the basis of the results of my trip of 1933, I re-examined the list of the chapels which the biography attributes to Rin-chen-bzari-po and I corrected, with the new and incontestable documentation, some of the identifications proposed by me beforehand.

The research is necessarily very technical, but it will seem all the more interesting when we think that Western Tibet is on the road to progressive depopulation and that the reconstruction of the historical geography of the region, difficult today, will in very little time be practically impossible.

Contents

| Preface | ||

| Synoptic view of the Book | xiii | |

| Twentyfour mandalas of STTS (4 samayas and 5 Kulas) | xvii | |

| The eighteen systems of Vajrasekhara yoga | xxiv | |

| Types of Mandalas of Vairocana | xxix | |

| Legend of Sudhana from the Avatamsaka sutra Gandavyuha (Rocana toVairocana) | xxxiv | |

| Amitabha and Amitayus | xxxvii | |

| Bhaisajyaguru | xlii | |

| Mara | xlii | |

| Literature cited | xliv | |

| Contents of the Main Book | ||

| 1 | The Historical Geography of Western Tibet | 5 |

| 2 | Diffusion of Sects | 17 |

| Chapter I Tabo. The Gtsug-lag-khan | ||

| 1 | General aspects of the Monastery | 21 |

| 2 | The Interior of the Gtsug | 25 |

| 3 | The Statues of the Gtsug-lag-khan represent a Tantric cycle of Vairocana | 28 |

| 4 | Some Tibetan sources on the cycle of Sarvavid Vairocana | 30 |

| 5 | The iconographical description of the thirty sevendeities of sarvavid | 32 |

| 6 | Indian sources of the cycle of Sarvavid and similar cycles | 36 |

| 7 | The Mandala of Vairocana according to Tattva sangraha | 39 |

| 8 | The Five mystical families and the five cycles | 42 |

| 9 | The Family of the gem (ratna -kula) | 43 |

| 10 | The Family of the lotus (Padma-kula) | 46 |

| 11 | The symbolic and esoteric meaning of the Mandala | 49 |

| 12 | The Significance of the Mandala of Sarvavid according to Tson-kha-pa | 55 |

| 13 | The main Mandala of Vairocana | 59 |

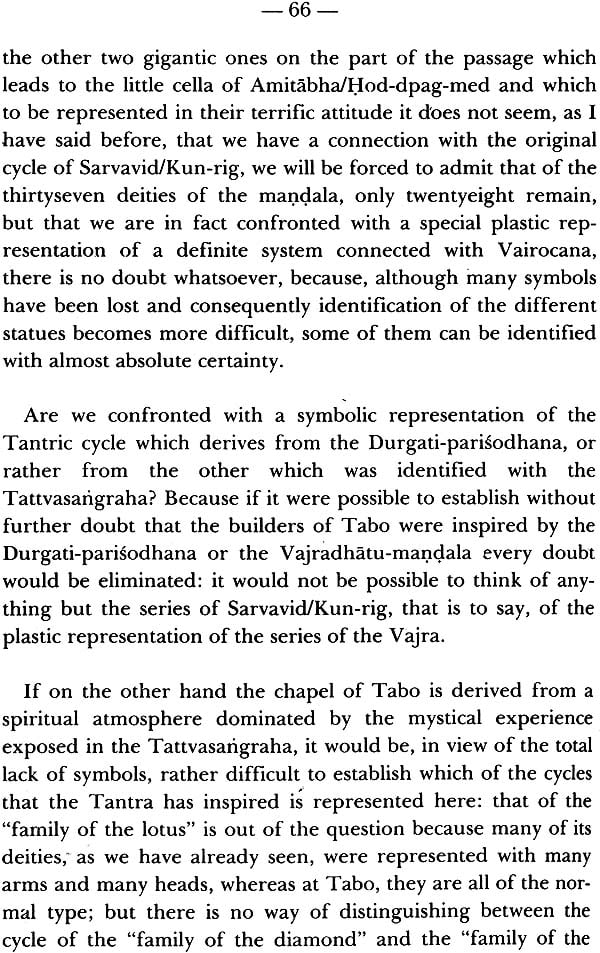

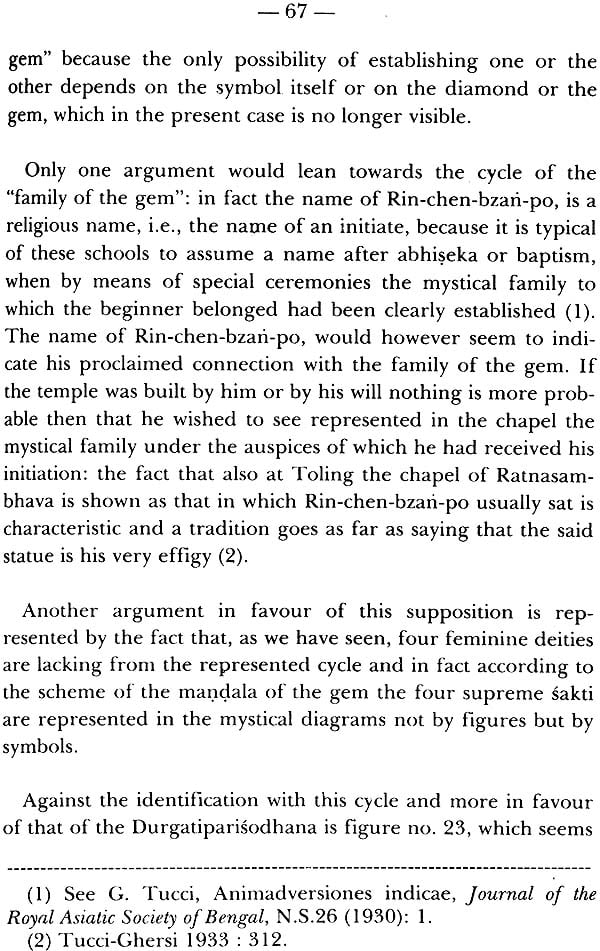

| 14 | Which cycle of Vairocana is represented in Tabo | 62 |

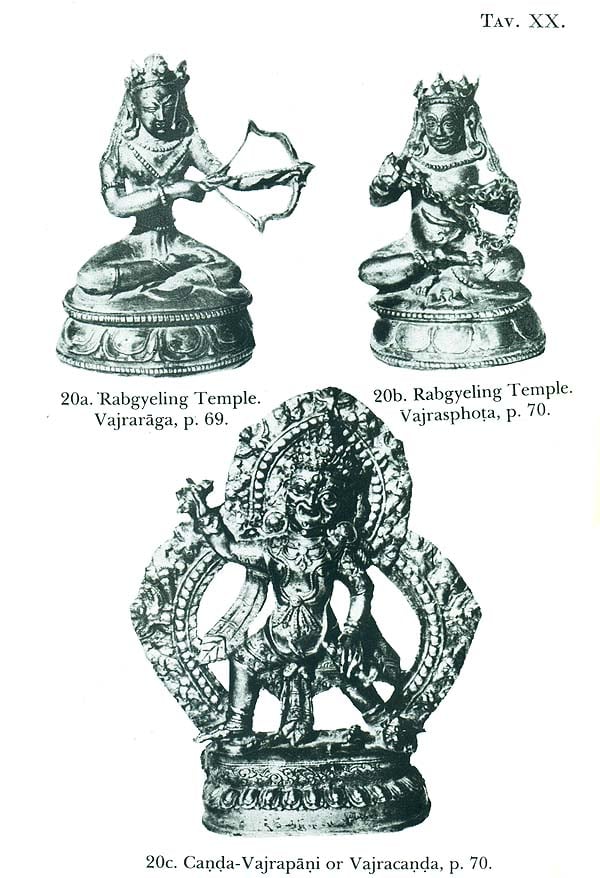

| 15 | Identification of the individual status | 68 |

| 16 | Iconographic types of Vairocana | 68 |

| 17 | Age of the Paintings at Tabo | 72 |

| 18 | The frescos | 75 |

| 19 | The Cella and Iconographic types of the Five Buddhas | 78 |

| 20 | Amitabha and Amitayus | 82 |

| 21 | Acolytes of Amitabha | 84 |

| 22 | The Library of Tabo | 86 |

| 23 | Two Kashmiri Sculptures | 89 |

| Chapter II Tabo. The Gser-Khan (Golden Hall) | ||

| 24 | The Gser-Khan and its paintings | 91 |

| 25 | Methods and meanings of Tantric evocations | 97 |

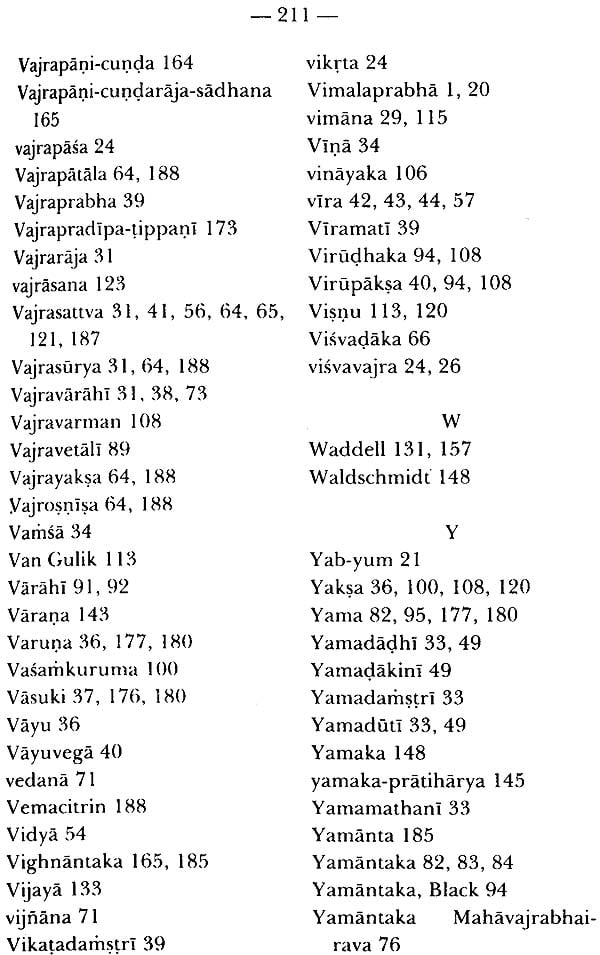

| 26 | The dharmapala and the Terrific in Tantric School | 105 |

| Chapter III Tabo. The Dkyil-Khan (Mandala Hall) | ||

| 27 | The Initiation Chapel | 109 |

| 28 | The Paintings of Historical Characters | 111 |

| Chapter IV Tabo. The Minor Chapels | ||

| 29 | Minor Temples | 114 |

| Chapter V Lhalung | ||

| 30 | New Cycle of Vairocana Represented at Lhalung | 116 |

| 31 | The central wall | 118 |

| 32 | The Prajnaparamita | 130 |

| Chapter VI The Temple of Chang (High Kunavar) | ||

| 33 | The Cycle of Naraka or of the Internal Deities | 130 |

| 34 | The Cycle of Naraka on Thankas | 135 |

| 35 | Minor Paintings | 138 |

| Chapter VII Nako | ||

| 36 | The Gompa Attributed to Rin-chen-Bzan-po | 141 |

| 37 | Mystical meaning of the Supreme Pentad | 145 |

| 38 | Equivalences of the Pentad | 151 |

| 39 | The Saktis of the Pentad | 155 |

| 40 | The Temples as Mandalas | 159 |

| 41 | Ornamental motifs of the type of Tibetan Garuda | 162 |

| 42 | The Bhaisajyaguru/Saman-bla or the Gods of Medicine | 162 |

| 43 | The Temple of Padmasambhava | 172 |

| Appendices | ||

| I | From a Manuscript of Pranjnaparamita | 177 |

| II | From a Manuscript of Durgati-Parisodhana | |

| III | From a Manuscript of Lokaprajnapati | 178 |

| IV | From a Fragmentary Manuscript | 179 |

| V | From the chronicles of the Fifth Dalai Lama Dza 46 | |

| VI | The Mandala of Sarvavid | 189 |

| VII | The Forty-Eight Goddesses of | 191 |

| VIII | Inscriptions of Tabo (Text) | 195 |

| IX | Inscriptions of Tabo (Translation) | 198 |

| Index | ||

| Plates I-XCI | ||

| Map of Diffusion of Sects | ||

| Map of the Valley of chandra and Spiti |

Part-II

SYNOPTIC VIEW OF THE BOOK

This volume of the Indo-Tibetica is dedicated to the six temples of Tsaparang, the first two named after their central deity namely Samvara and Vajrabhairava and the remaining four termed by their general characteristics: the White Temple, the Red Temple, the Temple of the Prefect, and the Lo-than dgonpa. These temples are unique examples of early Tibetan mural paintings as well as sculptures, all direct derivations from Indian traditions, and some of them even from the brush of Indian masters. In the feminine deities frescoed on the walls we can discern the continuation of the tradition of Indian miniatures. Professor Tucci speaks at length about the importance of the art of the chapels of Tsaparang in his introduction. He discusses the evident traces of Indian inspiration in the accuracy of execution, the delicacy of drawing, chiaroscuro effects, figures in profile rather than in frontal aspects, and so on. The art of Tsaparang has unique importance for the last phase of Buddhist art in India, especially in its Kashmiri idiom. The vanishing murals and images of the great Kashmiri monasteries evoked the admiration of Somendra the son of Ksemendra as early as the eleventh century. Already then, the light of Buddhism and its artistic glories were flickering out in Kashmir. Ksernendra set himself to capture the moral purity, enlightenment and beauty of the fading cloister walls in the varied flow of metres in the Avadana-kalpalata, as his son Somendra says in the l08th chapter:

"Gone are the monasteries in the flow of time whose cloisters were painted with charming murals of Buddhist avadanas in golden hues and which held the eyes in rapture. My father has collected these edifying tales, painted them in variegated hues of the poetic art, and it has verily become a magnificent and sanctifying vihara that transcends oblivion even by time".

The agony of this void found an epiphany in the work of Tsaparang artists in all the purity of faith and faithfulness to the original inspiration.

Vira, daka. The twentyfour deities in the Samvara-mandala are termed viras (NSP text p. 27). Tucci calls them twenty- four viras throughout this book.

A number of anuttara yoga deities are termed vira. In Vaisnavism, the images are classified into "yoga, bhoga, vira and abhicharika varieties in consequence of certain slight differences in their descriptive characteristics. These varieties are intended to be worshipped by devotees with different desires and objects in view: thus, the yogi should worship the yoga form of Vishnu, the persons who desire enjoyment should worship the bhoga form, those who desire prowess the vlra form, and kings and others who wish to conquer their enemies the abhicharika form". (Rao 1914: 1.79).

When the deity is without his consort he is termed eka-vira that is, the solitary or lonely hero. In the Sanskrit titles of works in the Tanjur, ekavira refers to Cakrasarnvara or Samvara (Cordier 2.40113.11, 2.46113.41, 3.102-103173.13, 14, 15, 3.104173.19). It is applied to Heruka in. Ekavira Heruka-sadhana (ibid. 2.43/13.25), Ekavira-sodasabhuja- sriHeruka-sadhana (ibid. 2.86/21.59). It should apply to Hevajra in Cordier 2.76/2l.8. In Cordier 2.338/69.9 and elsewhere the deity to which ekavira refers to is not clear.

The alternate title of candamaharosana-tantraraja is Ekalla- vira-tantra, which means that Candamaharosana a form of Acala is referred to as ekalla-vira (Filliozat 1941: 9 no.18), and Shastri (1917: 181-191 nos. 84, 85,87) has the title Ekallavira- candamaharosana-tantra.

The Greek heres denotes a famous hero promoted to divine rank. The heroes and hero-gods are a universal phenomenon. There are allusions to heroes in the classical and folk traditions of India, for example, •Hanuman of the Ramayana is a heroic god. Epic heroes like Rama and Krsna reached the highest rank. The belief in heroes plays a very important part in the development of Greek religion (ERE. 6. 652). The promotion of a hero to the status of a god was common in Greece: the god Dionysus is addressed as a hero in the old ritual chant of Elis. The worship of heroes as gods was firmly established in Greece from the seventh century B.C. (ERE. 6. 655).

Heruka. The word Heruka is used in two meanings, specific and generic: (i) Heruka proper and (ii) Heruka as a generic term of the classification of the yogini-tantras. In the first he is an independent deity in his own right, as in the nine-deity mandala of Heruka in the Nispanna-yogavall (text p. 20) where he has four forms with two, four, six and sixteen arms. The second meaning of Heruka is generic, as he is the head of the Buddha-kula of the anuttara-yoga tantras. In this capacity Heruka is equivalent to a Buddha and he heads the die ties Samvara, Hevajra, Buddhakapala, Mahamaya, Arali (Wayman 1973: 235). At times Cakrasarnvara is referred to as Heruka, but that does not mean that Heruka Cakrasamvara or vice versa. It simply implies that Cakrasamvara belongs to the larger group of the hypostases of Heruka.

Tucci comments on p.22 that Heruka is called Samvara as the central deity of the mandala. In the Nispanna-yogavali Heruka proper has two, four, six or sixteen arms (text p.20- 21), while Samvara has twelve arms (text p.26). The present mandala of Tsaparang pertains to Samvara. Thus on p.48 too the central deity has to be named Sarnvara and not Heruka. The etymology of Heruka is not clear. Its phonetics reminds of the Greek herii-s + 'hero', heros 'Eros, the god of love', and heruko 'to keep in, hold back, restrain, hinder; to control, curb, keep in check' (Liddell and Scott, Greek-English Lexicon , Oxford 1916). Eros brings to mind the yab-yum form of Heruka coupled with his consort (prajna) Nairatma. All the gods of the Heruka group are coupled with their goddesses. The word heruko 'to restrain, etc.' recalls samvara 'vow'. Edgerton (1953 : 539) translates samvara 'restraint, control, obligation, vow'. The Tibetan equivalent sdom-pa also covers the same semantic spectrum 'restraint, obligation, vow'. Pratimoksa-samvara are 'the moral restraints imposed in the code called Pratimoksa'.

The word daka is equal to antaka in Padma-daka = Padmantaka. The Tamil word takku means '1. strength, robustness. 2. petulancy, pride' (Tamil Lexicon 3.1696). Do daka and vira converge? In Tibetan daka is translated as mkhah,-hgro 'skygoer and its feminine form dakini as mkhah-hgro-ma 'the skygoing female'.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE TEMPLES OF TSAPARANG FOR THE STUDY OF TIBETAN ART.

This second volume on the temples of Western Tibet is exclusively dedicated to Tsaparang.

About Tsaparang I have already spoken in my diary of the travel of 1933 (1). There is no need to repeat here what I have already said or to describe the region again. It is useful only to remember that the place is an immense ruin today (Plate I). Only the temples remain of .its glorious past, and they also are desecrated, in danger to fall, and if the Tibetan authorities do not provide for them in time they are fated to crumble down.

In this way monuments of Indo- Tibetan art, of great value from the point of view of history, iconography and aesthetics will disappear. In fact, the temples which still remain, have long panels of tantric deities in many colours. In them are expressed with inexhaustible imagination, a great portion of the Mahayanic Olympus, but there is also a harmony of colours which was never again reached in these parts of Tibet. Their paintings represent the best productions of the Western Tibetan schools. In them we may admire the full maturity of an art which, as I have said elsewhere, is of direct derivation from Indian traditions. The masters, invited to the province of Guge at the time of Rin-chen-bzan-po and of his royal patrons around the millenium, introduced the artistic manner of their original regions and in this school of painting are still alive the shadows of the great Indian monasteries, which have survived the slow and fateful dissolution of Buddhism. The Tibetan disciples had continued it with great fidelity and with a reverential respect with which the neophytes maintain the inheritance of their masters.

This is the great value of the frescoed chapels of Tsaparang: in them, in fact, we can still admire the not undignified work of a school of painting which can be said to represent a province of Tibetan art well defined in characteristics and peculiarities of style. It is still totally free from Chinese influences that are seen very strongly in the more recent paintings. Since only these are generally known in Europe, it is natural that the historians of Oriental art have in general considered Tibetan paintings as a more or less direct affiliate to the Chinese. It is beyond doubt that when cultural and political relations of Tibet and China start gradually growing, while those with India start diminishing, the art of the Land of Snows was influenced by the Chinese. But here, in Western Tibet, we are in very different conditions. In fact, even if during the greatest flourishing of Guge's reign Chinese caravans were coming to Tsaparang (as can be deduced from the testimonies of Catholic missionaries and by the indirect documentation of the historical frescoes painting foundations of temples where occasionally Chinese merchants are also represented), nevertheless, the not always friendly relations with Central Tibet and the geographical distance, were two elements contrary to the penetration of cultural motifs from China in this far-away region. The relations with India, instead, starting with the time of Rin-chen-bzan-po, were never interrupted both via Kashmir and via Nepal.

On the other end, we know that in Western Tibet also, the work of Rin-chen-bzan-po, of his students and of his patrons was not only an intelligent apostolate, but a progressive work of civilizations made through the constant penetration of Indian motifs. This penetration was at the same time a creation because Buddhism and its missionaries found here only large groups of shepherds and mostly nomads. It is to say that, as the biography of Rin-chen-bzan-po teaches us, whole schools of artists came to live in Western Tibet and slowly they formed a school, where they however left traces of their personal work. The fragments of wooden sculpture published by me in the previous volume, the doors of Tabo, Toling, Tsaparang and Khojarnath are without doubt the few surviving documents of these masters' schools that the piety of the kings of Guge and the sad political events of India collected on the deserted planes of Mnah-ris.

These wooden works are conserved in large numbers. Never- theless, . an ancient frescoed chapel has survived for us. This chapel has to be considered as being due to the brush of Indian masters. I want to point to the chapel of Mangnang. This chapel, as I have already hinted at elsewhere and later I shall demonstrate in a more lengthy manner, has revealed to us suddenly a great monument of Indian painting where worthily survive the pictorial traditions till now known to us only through Ajanta, Ellora and Sigiriya. Here in Tsaparang the first stage is lacking. As always happens in important cities mostly subjected to political events, the most ancient pictorial documents, even if they were there, were substituted by new frescoed walls, du-ring the successive rebuilding of the temples. Nevertheless, if the point of departure such as we find in Mangnang is there no more, the pictorial processions preserved in the surviving temples, allow us to have an idea of the evolution of the schools which we shall call of Guge. If in any case it cannot be said, as it can be said for Mangnang, that we are facing Indian works, it is nevertheless certain that we witness a slow adaptation or acclimatization of painting in the temples of Tsaparang. They assume characters and forms peculiar to them without however loosing evident traces of the primeval Indian inspiration, also in the latest examples.

Contents

| Preface: Lokesh Chandra | xi | |

| Introduction the Importance of the Temples of Tsaparang for the study of tibetan Art | 5 | |

| Chapter I. The temple of Samvara/Bde-Mchog | ||

| 1 | General Description | 16 |

| 2 | The Cycle of Samvara/Bde-mchog | 17 |

| 3 | Iconographic type of Samvara and its symbolism | 22 |

| 4 | The mandala of Samvar | 27 |

| 5 | the twnetyfour viras and the cosmic man | 42 |

| 6 | Meaning of the mandala of Samvara | 44 |

| 7 | The mandala of Samvara as respresented at Tsaparang | 48 |

| 8 | The frescoes. The eight cemeteries | 50 |

| 9 | The Minor deities | 54 |

| 10 | The five Tathagatas | 59 |

| 11 | The 'Circle of protection" | 64 |

| 12 | The Ten Dakini | 65 |

| 13 | A terracotta Triptych | 74 |

| Chapter II The small Temple of Vajra-Bhairava/Rdo-rje hjigs-byged | ||

| 14 | General aspect of the temple | |

| 15 | The mandala of Vajrabhairava | 76 |

| 16 | Vajrabhairava | 78 |

| 17 | the mandala represented at Tsaparang | 85 |

| 18 | The minor deities | 92 |

| 19 | Remati in India and tibet | 96 |

| 20 | Other deities of the cyle of Bstan-srun ma | 104 |

| 21 | The series of the "masters" | 110 |

| Chapter III. The White Temple | ||

| 22 | General characteristics | 112 |

| 23 | The iconographic types represented in temple | 113 |

| 24 | Cycles of Vairocana | 117 |

| 25 | Amitabha or Sakyamuni | 122 |

| 26 | The Cella | 124 |

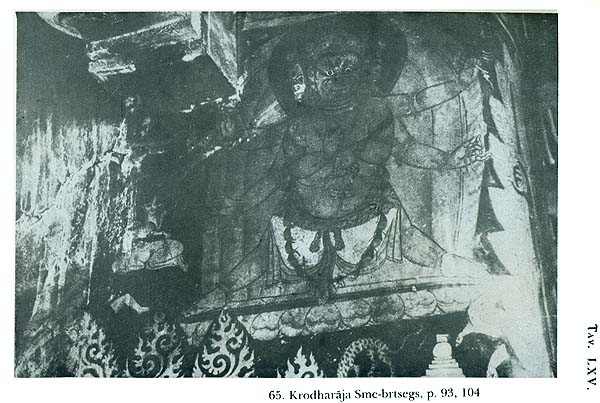

| 27 | The King of Guge | 127 |

| Chapter IV. The Red Temple | ||

| 28 | General description | 130 |

| 29 | The legend of the Buddha depicted | 133 |

| 30 | Scenes of the foundation of the temple | 151 |

| Chapter V The Temple of the Prefect | ||

| 31 | General Description | 155 |

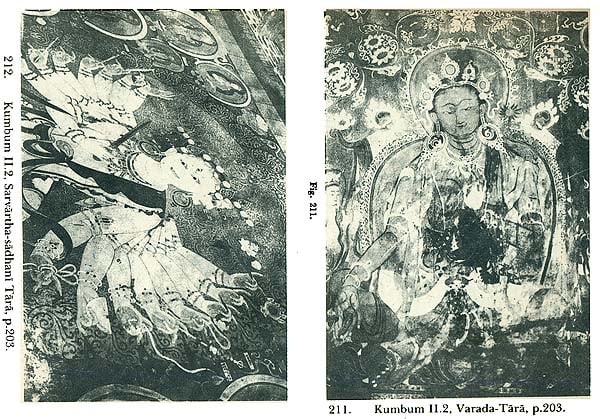

| 32 | The cycle of Tara | 156 |

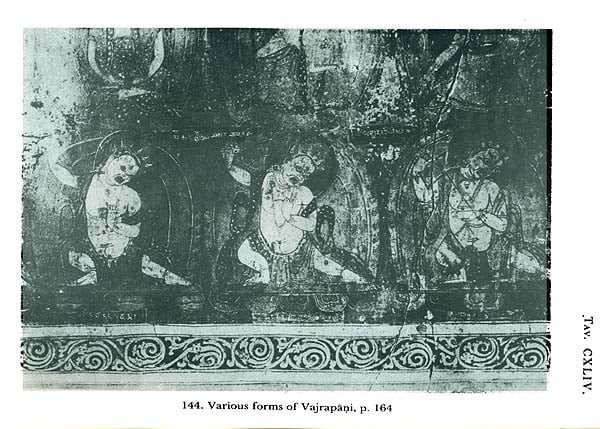

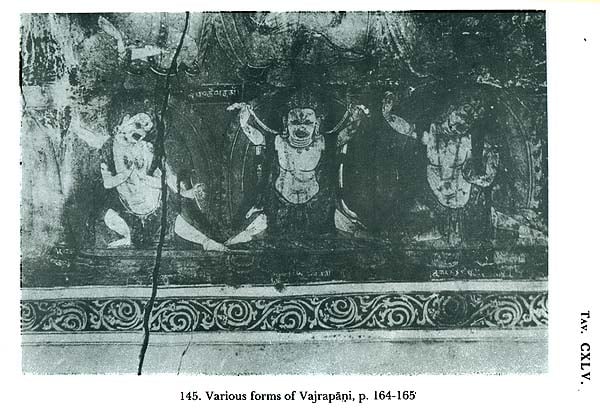

| 33 | The cycle of vajrapani | 164 |

| Chapter VI. The Lothan dgon pa | ||

| 34 | General description | 167 |

| Appendices | ||

| I | The eight cemeteries of liturgical literautre | 173 |

| II | The Thirtytwo deities of the cycle of guhyasamaja | 182 |

| III | the Cycle of protection | 187 |

| Bibliogrpahic List | 189 | |

| Index | 193 |

Vol-IV

Part-I

Fundamental studies on Tibetology are incorporated in the four volumes (seven bindings) of Professor Giuseppe Tucci' s Indo- Tibetica. As the work appeared in Italian, very few scholars have benefited by the' crucial results of Tucci' s investigations and perceptions. Moreover, Indologists hardly ever approached it, as Tucci used Tibetan terms like mchod-rten for stupa. The presented English version of the Indo- Tibetica will place at the disposal of Indologists, Tibetologists, Buddhologists, Historians, Anthropologists, Archaeologists and specialists in allied areas and disciplines, a basic work which presents new material from unpublished sources and unexplored monasteries on the frontiers of India and in bordering areas. Sanskrit equivalents of Tibetan terms have been used throughout to make the text accessible to a wider audience, for example, stupa (mchod-rten).

This volume is a major breakthrough for the history of the Sa-skya period of Tibet, the art treasures of the Gyantse region, and the evolution of a distinctive Tibetan style from the multiple strands of Indian iconographic elements, Chinese tendencies in larger compositions and the. Khotanese manner in statuary.

So far it had been held that Buddhism went to Tibet through Nepal and Kashmir, but this volume points out for the first time how it also traversed the Sikkim-Gyantse way.' It details the historical monasteries on the road to and in the city of Gyantse, which are of unique value for the development of the Tibetan visual arts. The small temple of Bsam-grub lha-khan near Phari has frescoes of the XV century and a statue of Avalokitesvara and two book covers of possible Indian origin. This book treats of the extraordinary flourishing of art due to the enlightened patronage of the Sa-skya-pas during the long tenure of their power. The princes of Zhalu and Gyantse followed their example. Chinese influences came to be felt during the hegemony of the Sa-skyas who maintained cultural and political relations with China for two centuries.

The volume reviews the disappearance of ancient historical records because of the suppression of all rivals by the emerging Gelukpa sect, The Myan-chun chronicles and the Eulogy of Nenying monastery, which have escaped, are unique sources for the 'history of the artistic heritage of the region. Along with them, historical geography, the chronologies of the Sa-skya abbots and of the princes of Zhalu and of Gyantse, and their relations with the Mongol court are discussed.

The monastery of Kyangphu at Samada was founded in the XI century, but was restored in the XIV under the Sa-skyas. It has statues and stupas of Indian origin. Its surviving murals betray Central Asian style. Several mandalas of Vairocana from different tantras are dealt with. The Gyani monastery in the Salu village has capitals of the XIV century. The monastery at Iwang was constructed before the arrival of Sakyasrt the Great Pandit of Kashmir in the XIII century. An inscription on its mural says that it was painted in Indian style .Another inscription points out that Amitayus was done in the Khotanese way. The ancient monasteries of Shonang and Nenying have been restored and repainted, though at Nenying splendid fragments of the best epoch of Indo-Nepalese art survive.

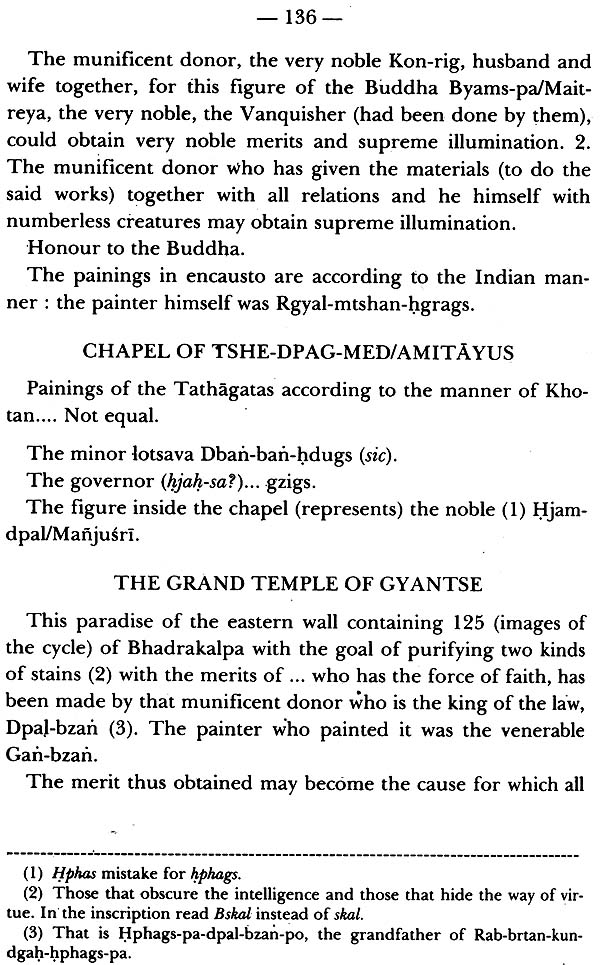

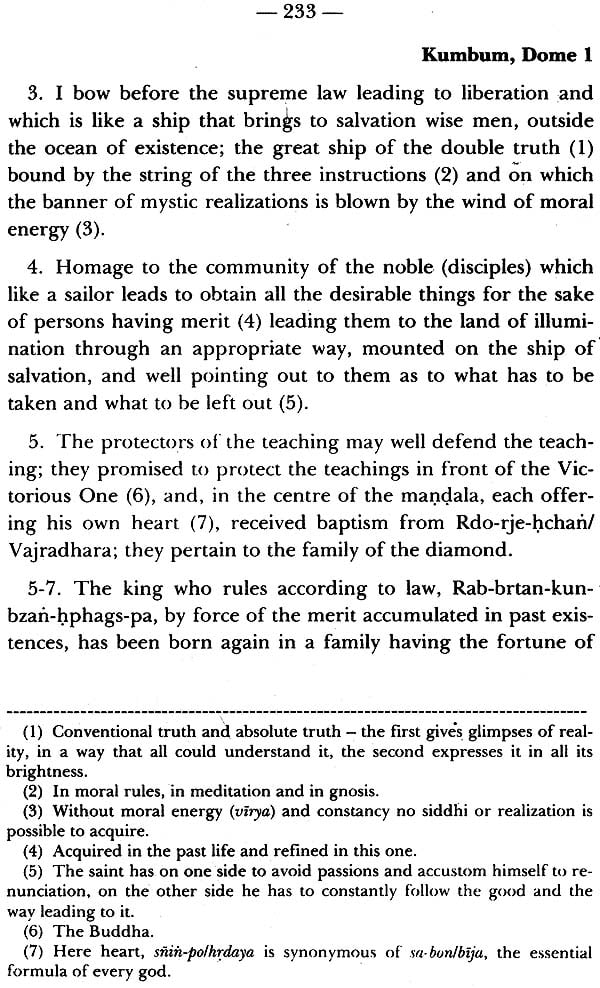

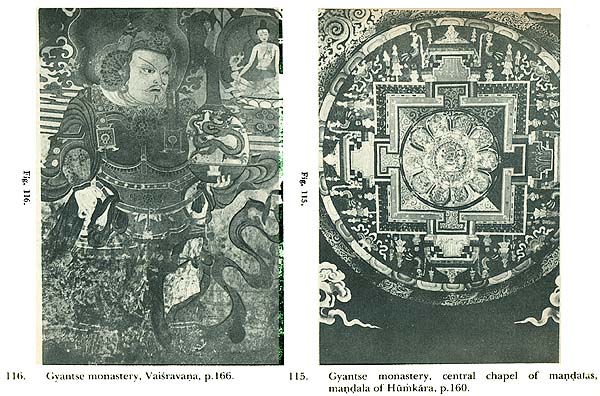

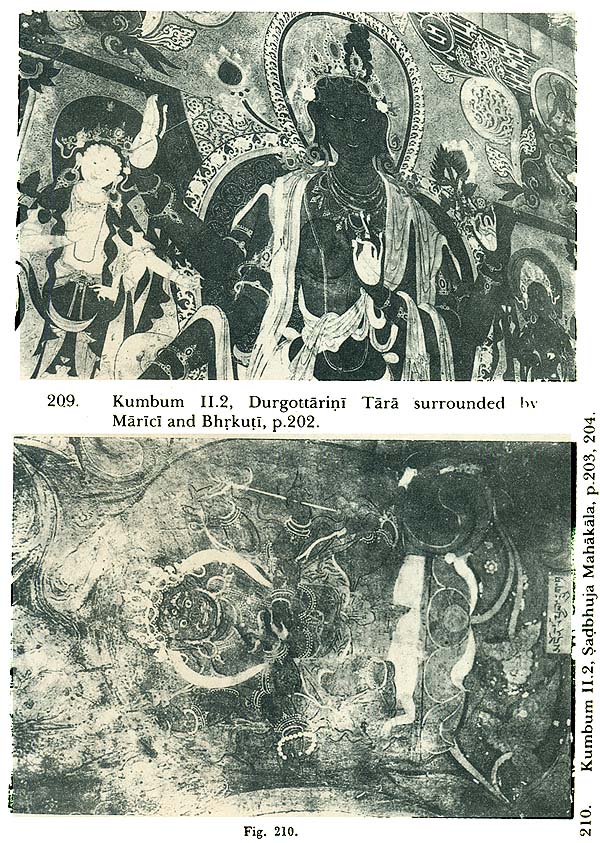

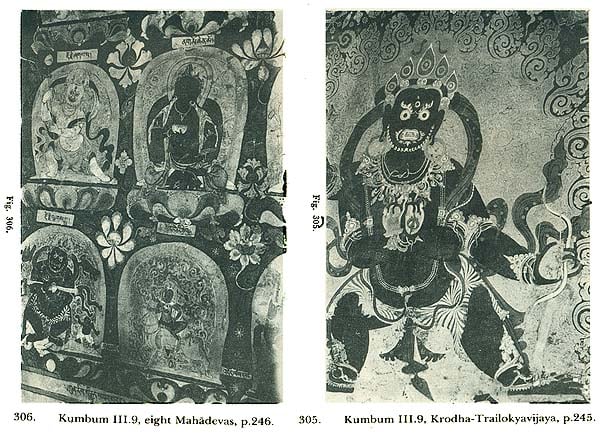

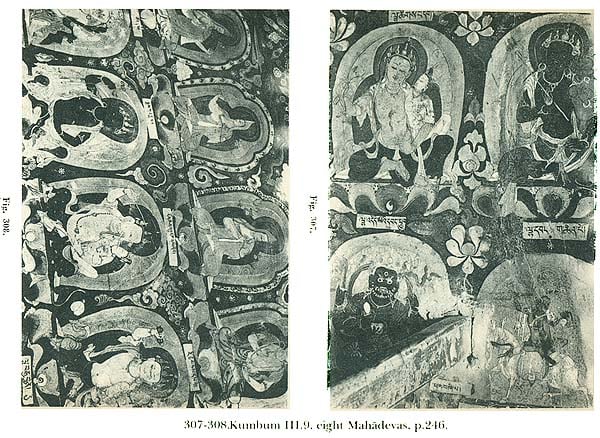

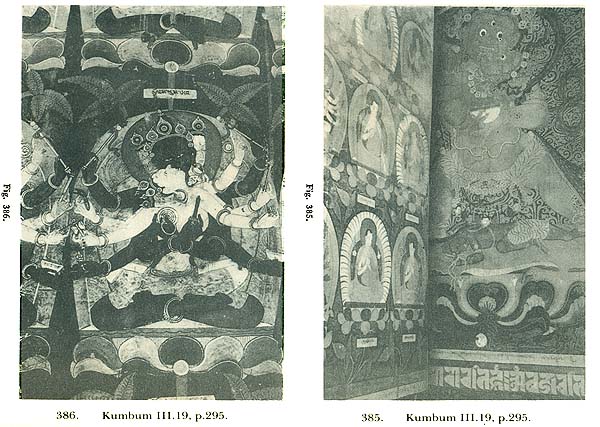

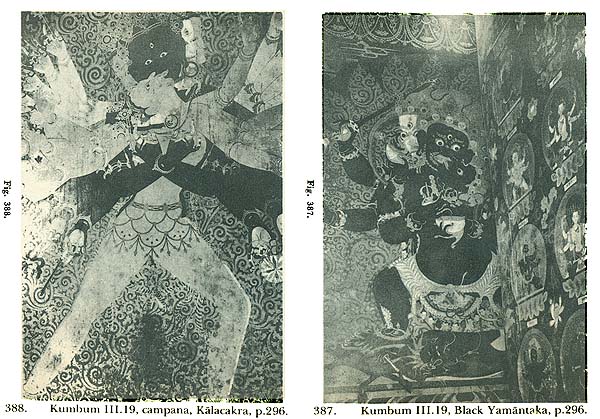

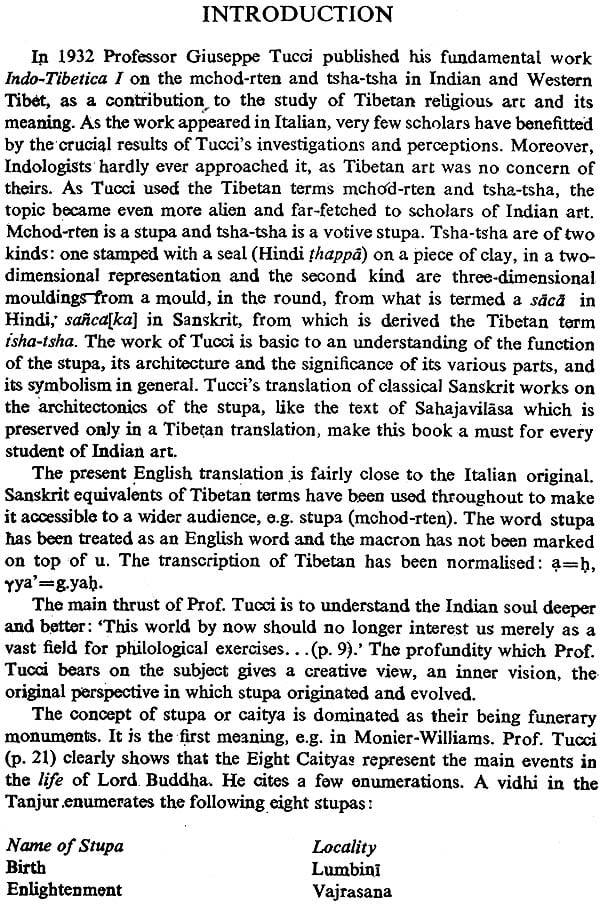

The superb monastery of Gyantse is described in all scientific details for the first time in 'this book. The most outstanding monument of the region is the Kumbum of Gyantse,: also known' as Dpal-hkhor chos-sde, important both for its architecture and for its paintings. It is a gigantic complex of several mandalas, a veritable summa of tantric revelations. The inscriptions name its painters and sculptors: unique in the history of Tibetan art. They give summary descriptions of the frescoes which serve as remarkable iconographic guides. The paintings can be dated to a well-determined period, 'namely the XV century, when an independent idiom of Tibetan art developed.

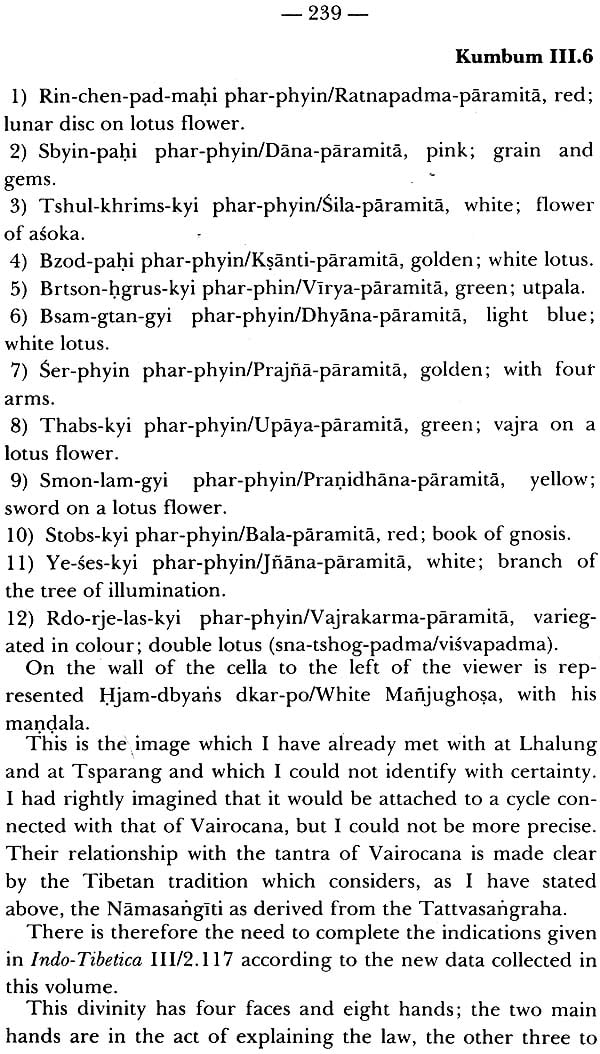

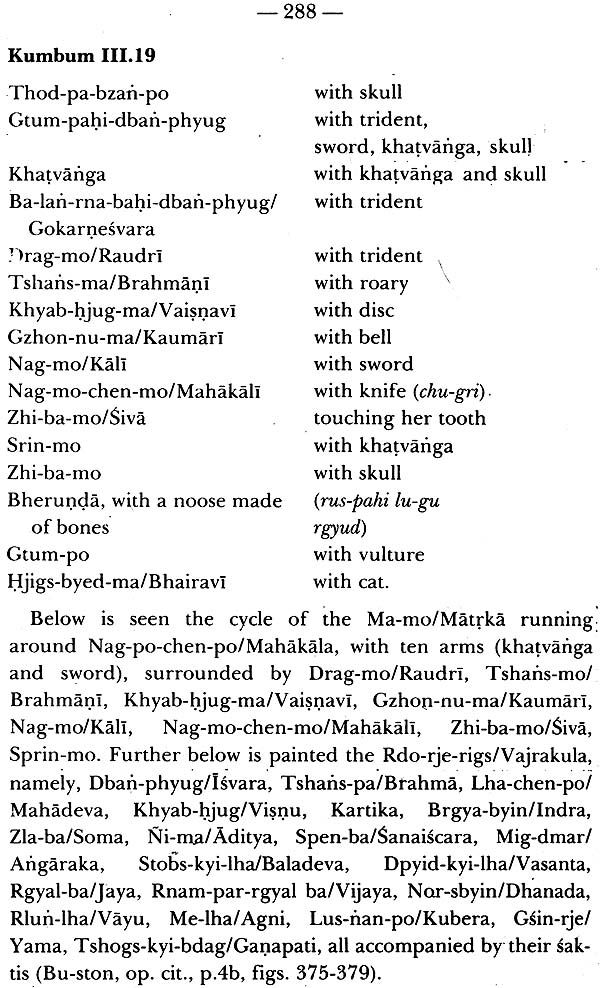

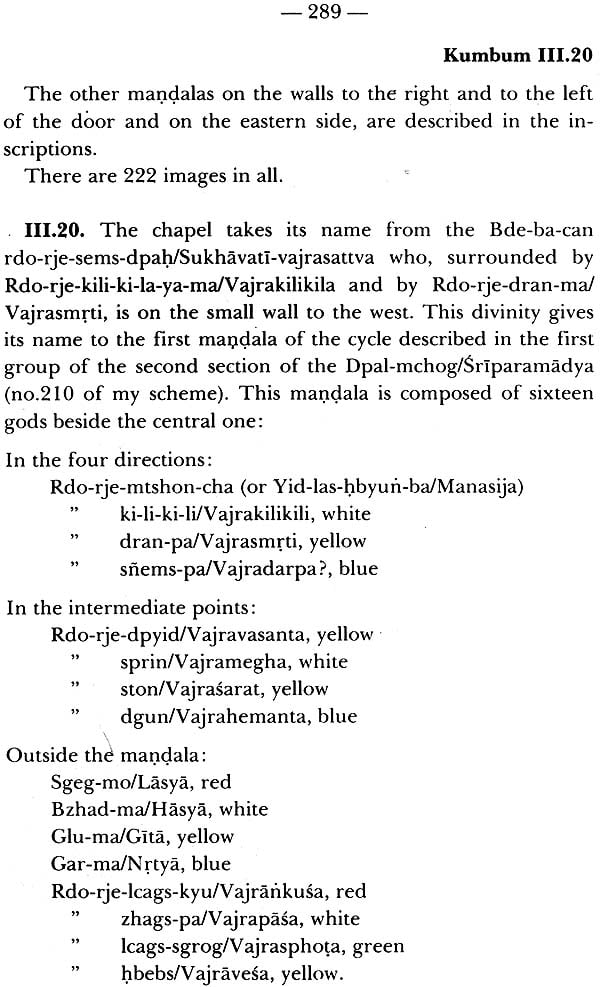

Part 1 details the iconography of the Kumbum which is an architectonic mandala, where progressive ascending from one floor to the other corresponds to an ascension from a lesser order of tantras to ever higher ones. The 73 major temples and minor chapels on its four floors and dome are described at length. An astounding number of 27,529 deities are represented in the. Kumbum. This book is a mine of information and perceptions of 'the great master Giuseppe Tucci, and invites, further researches on the vast tantric iconography and its symbolism detailed herein. Part 2 gives the text and translation of the inscriptions in the temples and chapels of the various monasteries. Part 3 is devoted to the mural paintings in them.

The transmission of Buddhism to Tibet had so far been held to be through Nepal and Kashmir; but this volume points out that it had also traversed the Sikkirn-Gyantse way. Near Phari is a small temple Bsam-grub lha-khan which has frescoes of the XV century and a statue of A valokitesvara and two book covers of possible Indian origin.

The most outstanding monument of the region is the Kumbum of Gyantse, also known. as Dpal-hkhor chos-sde, important both for its architecture and for its paintings. It is a gigantic complex of several mandalas, a veritable summa of tantric revelations, compiled in encyclopaedic works like the Sgrub-thabs- rgya-mtsho or grub-thabs-kun-btus. The inscriptions name the painters and the sculptors who are unique for the history of Tibetan art. They give summary descriptions of the frescoes which serve as remarkable iconographic guides. The paintings can be dated to a well-determined period, namely, the XV century when an independent idiom of Tibetan art developed. Chinese influences can be felt during the Sa-skya hegemony, who maintained cultural and political relations with China for two centuries. The Chinese manner is evident in scenes •of paradise, landscapes, palaces, floral plays, clouds hanging in the air. The Indian style is strong in. the mandalas. Central Asian style from Khotan, the Li-lugs, is evident in the statues of Iwang. The Indian elements in the iconography and the Chinese tendencies in the larger' compositions mature into a Tibetan aesthetic sensibility.

The flourishing of art was due to the enlightened patronage of the Sa-skya-pa during the long tenure of their power. The princes of Gyantse followed their example. In course of time, the Dge-Iugs-pa sect became predominant. The chronicles of the earlier rival sects and of families in whom these lands vested, disappeared gradually. The Dge-Iugs-pa suppressed the historic works that were not to their liking. Thus the Eulogy of Gnas-rnin has survived only in personal libraries, and the Myan-chun annals are very hard to find. Both these texts provide precious and extensive data on the monuments at Gyantse. The chapels are described in detail; all the books and statues in them are enumerated in full. The Myan-chun, a guide to the antiquities of the Gtsan region, has been utilised for this study besides four other secondary sources.

Historical geography and a general survey of the ancient monasteries in Upper, Middle and Lower Nan from the third chapter of the book.

The fourth chapter is devoted to the chronology of the monuments and of their founders the Sa-skya-pa abbots. Complete hierarchy of the abbots has been worked out anew on the basis of the Blue Annals and Chinese works. Some basic dates like the foundation of the Sa-skya monastery in 1073, the birth of Kun-dgah-snin-po in 1092, the birth of Sa-skya Pandita in 1182 werq already known from the Vaidurya-dkar-po, through the researches of Korosi Csoma Sandor. The chronology can be compared with the Sa-skya genealogy composed by Bu-ston. Another coordinate to fix definitive points is the genealogy of the princes of Zha-Iu and Gyantse from the Myan-chun. These can also be confirmed by correspondences with the Mongol emperors. The founder of the local dynasty that ruled over Gyantse was Hphags-dpal-bzan-po in the XIV century (p.82f.) The princes of Zhalu were invested with supreme authority by the Sa-skya-pas, with whom they had bonds of kinship (p.84f.). Zhalu was the monastery where Bu-ston worked and which he embellished.

On p. 29 Prof. Tucci says that bkod-pa denotes the scheme of the disposition of figures in the mandala. This Tibetan word is an equivalent of vyuha in the Mahavyutpatti, It occurs as early as the Sukhavati-vyuha which may be assigned to the first century A.D. The concept of vyuha or a large number of Tathagatas and beings in the congregation of the main deity is an ancient idea. In the smaller Sukhavati-vyuha, in the east are other blessed Buddhas, led by the Tathagata Aksobhya, the Tathagata Merudhvaja, the Tathagata Mahameru, the Tathagata Meruprabhasa, and the Tathagata Manjudhvaja. In the south are: the Tathagata Candrasuryapradipa, the Tathagata Yasahprabha, the Tathagata Maharciskandha, the Tathagata Merupradipa, the Tathagata Anantavirya. In the west: the Tathagata Amitayus, the Tathagata Amitaskandha, the Tathagata Amitadhvaja, the Tathagata Mahaprabha, the Tathagata Maharatnaketu, the Tathagata Suddharasmiprabha. In the north: Tathagata Maharciskandha, the Tathagata Vaisvanara-nirghosa, the Tathagata Dundubhisvara-nirghosa, the Tathagata Duspradharsa, the Tathagata Adityasambhava, the Tathagata Jaleniprabha (jvaliniprabha ?), the Tathagata Prabhakara. In the nadir: Tathagata Simha, the Tathagata Yasas, the Tathagata Yasahprabhava, the Tathagata Dharma, the Tathagata Dharmadhara, the Tathagata Dharmadhvaja. In the zenith: Tathagata Brahmaghosa, the Tathagata Naksatraraja, the Tathagata Indraketudhvajaraja, the Tathagata Gandhottama, the Tathagata Candhaprabhas, the Tathagata Maharciskandha, the Tathagata Ratnakusuma-sampuspitagatra, the Tathagata Salendra-raja, the Tathagata Ratnotpalasri, the Tathagata Sarvarthadarsa, the Tathagata Sumerukalpa (Max Muller, SBE.49, 1894: 100-101). The vyuha is the initial stage in the emergence of the mandala.

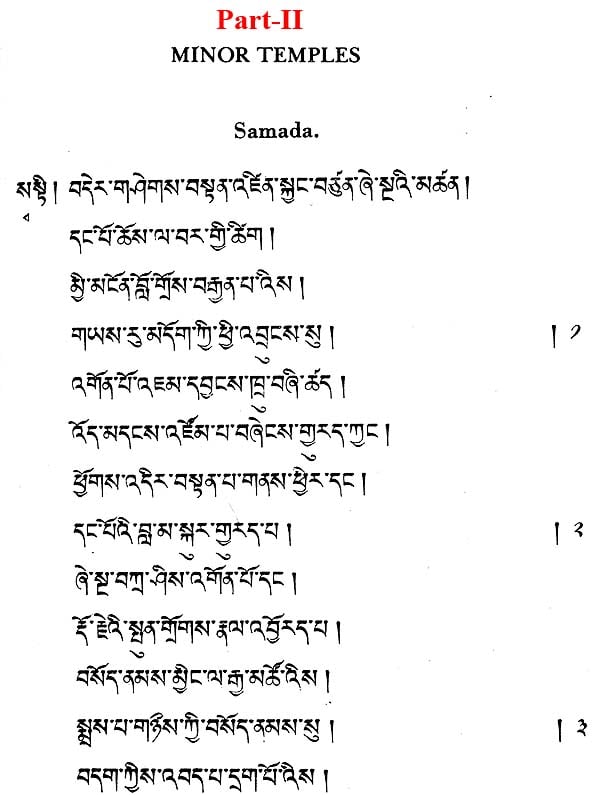

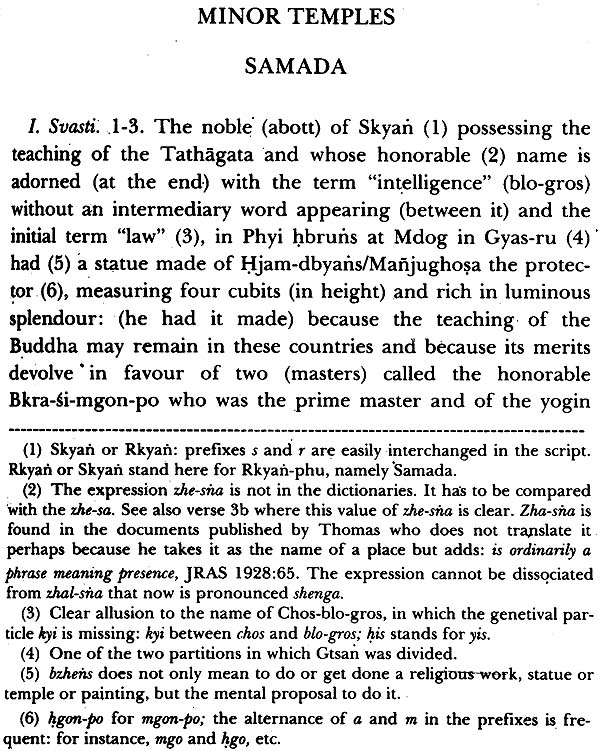

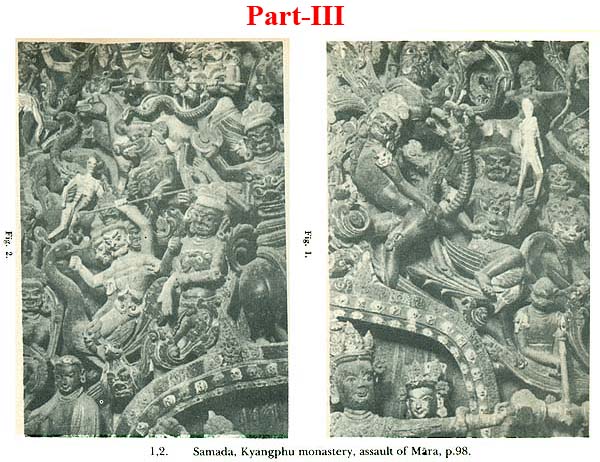

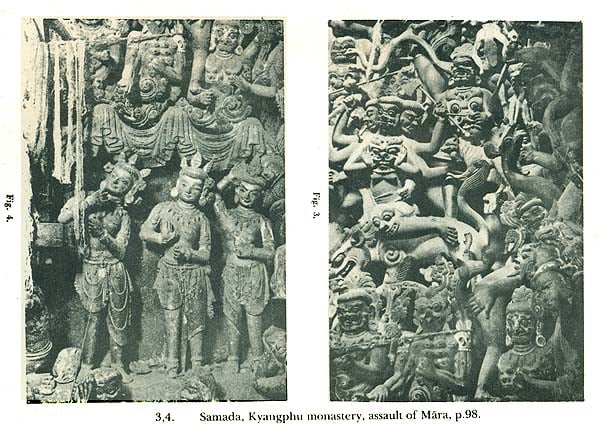

Two monasteries of Kyangphu and Riku situated at Samada deserve notice. The first monastery is famous in tradition as the oldest. The present structures however date to the XIV century. Entering through a narrow gate we see small cellas, one is the mgon-khan and the other on the right is dedicated to Lha-mo. In the court the first chapel is Sakyamuni's victory over Mara, In the atrium of the main temple are frescoes that remind of the style of India. The temple was founded by Chos-kyi-blo-gros, a disciple of Rin-chen-bzan-po. The first chapel of the main temple is called the southern chapel. Its altar has statues of Indian origin (p.100). The magnificent stupa behind the altar is of gilded bronze with the Vajradhatu-mandala in high .relief. Executed with extreme finesse it can be a work of the late Pala period. The other chapel to the left is the big northern chapel which has statues of the Buddhas of the past, future and present: Dipankara, Maitreya and Sakyamuni. The most important objects herein are the pediments of three statues of the three protectors: Avalokitesvara, Vajrapani and Manjughosa. The extant image of Avalokitesvara is of Indian origin. The metrical inscription indicates that it was ordered by Chos-kyi-blo-gros, a disciple of Rin-chen-bzan-po. He in fact was the founder of the Kyangphu monastery in the XI century but it was restored during the Sa-skya period in the XIV century. On the first floor there are two chapels. The right chapel is dedicated to Sarvavid Vairocana (p. 106). Professor Tucci dilates upon the several cycles of Vairocana to determine the mandala in this chapel. He comes to three main figurations of the mandala of Vairocana, based on the Tattva-sangraha, Vairocanabhisambodhi and Durgati-parisodhana. The mandala in the right chapel is derived from the Tattva-sangraha. To the left is the chapel of Prajnaparamita (p. 130). To the left of the door is the image of Hayagrlva and to the right that of Acala (p. 121). The mural paintings surviving 'here and there on the second floor betray Central Asian style.

Leaving the village of Samada, half a kilometer down, is the monastery of Riku or Dregun. Some of the paintings can be ascribed to the XVI century. Its most ancient part is the Mgon-khan, with Gur mgon the protective deity of, the Sa-skya-pas, surrounded by the divinities of his cycle, Pu-tra min-srin (p. 130).

Prof. Tucci details the various mandalas of Vairocana from seven texts. He begins with the Tattva-sangraha, whose first section pertaining to abhisamaya has six mandalas classified as: (1) detailed, (2) intermediate, and (3) concise. There are four detailed mandalas, and .one mandala in each of the other two. The intermediate caturmudra-mandala is one cycle with Vairocana in the centre and the four Tathagatas in the four cardinal points. The four Tathagatas are not accompanied by other deities. Tucci assigns a mandala to each of them (6-9) which has to be corrected.

The first four mandalas are :

- Mahamandala : Vairocana in bodhyagri-mudra, pare and crowned, sits on seven lions, Gobu 1.

- Guhya-dharani-mandala with figures, or samaya-mandala with emblems : Vairocana is replaced by Vajrini or Vajradhatvisvari, crowned, seated on a lotus, holds a caitya on a pediment, Gobu 39.

- Dharma-mandala, or suksma-mandala vairocana in bodhyagri-mudra, pare and crowned addorsed by vajras, sits on on a lotus, Gobu 72.

- Karma-puja-mandala, Vairocana as a monk (neither pare nor crowned), sits on a lotus, Gobu 105.

In these four mandalas, the attributes of the 37 deities change and also their names. For a detailed study the introduction. to my edition of the Sarva-tathdgata-tatva-sangraha (STTS) has to be consulted, in conjunction with my A Ninth Century Scroll of the Yajradhatu-mandala. The latter work illustrates the six mandalas of the first abhisamaya section of the STTS by Subhakarasimha (A.D. 637-735) in a scroll termed Gobu-shinkan. The central deity of the first four mandalas is reproduced here from this scroll to show the variation pattern.

All the mandalas enumerated by Prof. Tucci from the STTS and other texts have to be re-defined, and their entourage clearly enumerated from the original tantra, from Classical commentaries, and from later reworkings. Thus, the nos. 15-19 is one caturrnudra-mandala and has to be assigned one number.

The Gyanil Rgya-gnas monastery was controlled by the Sa-skya-pas. Capitals in its atrium belong to the XIV century.

MONASTERY OF IWANG The monastery at Iwang is one of the important monuments of the region, as it had been constructed by Chos-byan a pre-incarnation of Sakyasri the Great Pandita from Kashmir who arrived here in the XIII century. It is divided into three chapels. The central chapel is dominated by Amoghadarsin, flanked by six Tathagatas, constituting the Seven Buddhas/Rabs-bdun. The mural paintings have preserved an inscription which says that Rgyal-mtshan-grags has painted in the Indian manner. The right chapel has Amitayus, with ten statues around. From the dresses, ornaments and shoes to the delicate colours, techniques of drawing and painting, all remind of Central Asia. The whole cycle has been transported from there. An inscription confirms that it has been done in the Khotanese way (Li-lugs). The left chapel represents the assault of demons ' on meditating Sakyamuni (p. 139). These works of art predate the emergence of the Tibetan style which can be seen at Kumbum with the most extensive pictorial panels of the XV century.

In 1937, I left for a new expedition in Tibet, which was sponsored by Prassitele Piccinini, who had already sponsored that of 1935. As it can be seen from these pages, the results we obtained are superior to those of the previous travels. It is therefore right that I express my thanks to Mr. Piccinini who has favoured this new expedition of the Academy of Italy in the harsh lands of Tibet, and has allowed me to discover such remarkable monuments of that Indo-Tibetan culture which day by day reveals itself worth studying.

Prof. Piccinini, leaving aside his major field of research in the medica) sciences, continues' with his generosity the humanistic tradition of our people. It is but natural that Italy deals with Tibet, because the Italians first made known to Europe, and not in a superficial way, the soul and the beliefs of these people so profoundly devoted to religious ideals (1). A book like that of Desideri does not become dated.

I must also thank Doctor Fosco Maraini who has been an intelligent collaborator and a good travel companion. He has done the entire photographic work, and the plates of this book are all by him.

I do not publish the diary of the expedition. Others have •gone to Gyantse before me and have described the land. I could not add new things. But I have discussed in this book the art monuments found along the roads and the reflections that can be made and the conclusions to be drawn for the study of the political, religious and artistic history of Tibet. This book includes many new things and much material investigated for the first time.

From Western Tibet I have gone to Central Tibet: but the geographical distance does not make a difference in culture. We are always faced by the same religious and artistic world and by the same spiritual unity.

This series of Indo- Tibetica which I slowly keep on writing and in which I describe the material collected in my scientific missions, has n0W come to its fourth volume, after six years of its starting.

Since I am working on a virgin ground and I am going on exploring day by day new sectors of the vast Tibetan literature, which still can be reached with great difficulty, it is right to look back and to ask ourselves. if the work already done would not require a revision of some points. To this effect I have read again and attentively the volumes of Indo- Tibetica already published and I have found that by and large I have not much to add or to modify .. I noticed, however, some inaccuracies or incomplete details. And because this series of Indo- Tibetica has to remain a unity they should be corrected. To those who have read the previous volumes I recommend to look at the appendix published herein where whatever should be considered wrong or imperfect, due to carelessness or to defect of information, has been completed or corrected.

Thus, the previous work has bee.n revised by the Zhu-che, and I am glad to have been the Zhu-che of myself.

Contents

| Foreword: by Lokesh Chandra | xi | |

| Preface | 1 | |

| Chapter I. Importance of the monuments studied in the trip of 1937 | ||

| 1 | The Sikkim-Gyantse road and its monuments | 5 |

| 2 | The importance of these monuments for the History of Tibetan art | 9 |

| 3 | The Lists of Sculptors and painters in the inscriptions of gyntse | 16 |

| 4 | Importance and Characters of the paintings in these monuments | 21 |

| 5 | Chinese in fluences on these paintings | 25 |

| 6 | Paintings in Indian style | 28 |

| 7 | Painters and paintings | 30 |

| 8 | The diverse elements by whose fusion Tibetan painting is born | 31 |

| 9 | The statues | 35 |

| 10 | Architecture | 38 |

| 11 | Importance of the Sa-skya-pa sect | 39 |

| Chapter II. Sources | ||

| 12 | Disappearance of ancient historical documents | 40 |

| 13 | The Myan-chun | 42 |

| 14 | The eulogy of gnas-rnin | 44 |

| 15 | secondary sources | 45 |

| Chapter III. Land of Nan | ||

| 16 | The land of Nan | 47 |

| 17 | The monasteries of nan-smad | 54 |

| 18 | Nan-bar | 66 |

| 19 | The Temples of Nan-smad | 68 |

| Chapter IV. Chronology of the monuments and especially that of the Kumbum | ||

| 20 | Chronology of the Sa-skya abborts | 73 |

| 21 | The princes of Zha-lu and Gyantse | 78 |

| 22 | The Sa-skya monks and the Mongol court | 84 |

| Chapter V. The Temples of Samada | ||

| 23 | General Characteristics | 93 |

| 24 | The mgon-khan | 93 |

| 25 | The chapel of the victory over Mara | 97 |

| 26 | The atrium and the first chapel | 98 |

| 27 | The inscriptions of Chos-blos and the foundation of the temple | 101 |

| 28 | The Mudra of Rnam-par-snan mdzad/Vairocana | 106 |

| 29 | Scheme of the Mandalas of Rnam-par-snan-mdzad/Varocana described in the preceding volumes | 108 |

| 30 | Vajradhatu-mandala and Mahakaranagarbha-mandala | 110 |

| 31 | Why the mandalas of a single cycle can be many | 113 |

| Mandalas: | ||

| 32 | From Rtsa rgyud: Tattvasangraha/De-nid-bsdus | 130-121 |

| 33 | From Vajrasekhara (Toh. 480) | |

| 34 | From Sri-Paramadya-tantra (Toh. 487) | |

| 35 | From Nama-sangiti (Toh.360) | |

| 36 | From Vairocanabhisambodhi (Toh.494 and affiliated text | |

| 37 | From SripVajramandal-alankara (Toh 490) | |

| 38 | From Sarvadurgati-Parisodhana (Toh 483) | |

| 39 | The mandala of Samada represents the vajradhatu-mandala | 130 |

| 40 | The cycle of Mon-bu putra in the temple of Dregun (samada) | 130 |

| Chapter VI. Salu, Iwang, Shonang and Gnas-rnin Salu | 133 | |

| 41 | The chaptel of Iwant embellished in the Indian Manner | 134 |

| 42 | The chapel embellished in the Khotanese manner shonang | 138 |

| 43 | The foundation of the monastery of Gnas-rnin | 142 |

| Chapter VII. Gyantse and its main temple | ||

| 44 | The three chapels on the first floor | 146 |

| 45 | The chapel of Lam-bras | 153 |

| 46 | The chapel of Mandalas | 158 |

| Chapter VIII. Kumbum | ||

| 47 | General Symbolism of the kumbum | 168 |

| 48 | The first floor of the Kumbum | 172 |

| 49 | The Second floor of the Kumbum | 201 |

| 50 | The Third floor of the Kumbum | 218 |

| 51 | The Fourt floor, the dome and the campana of the Kumbum | 290 |

Part-II

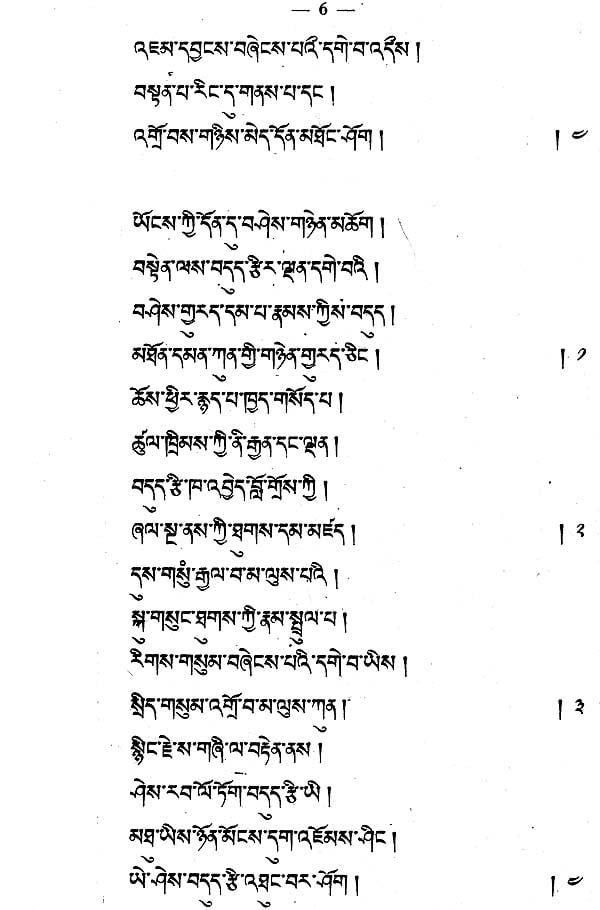

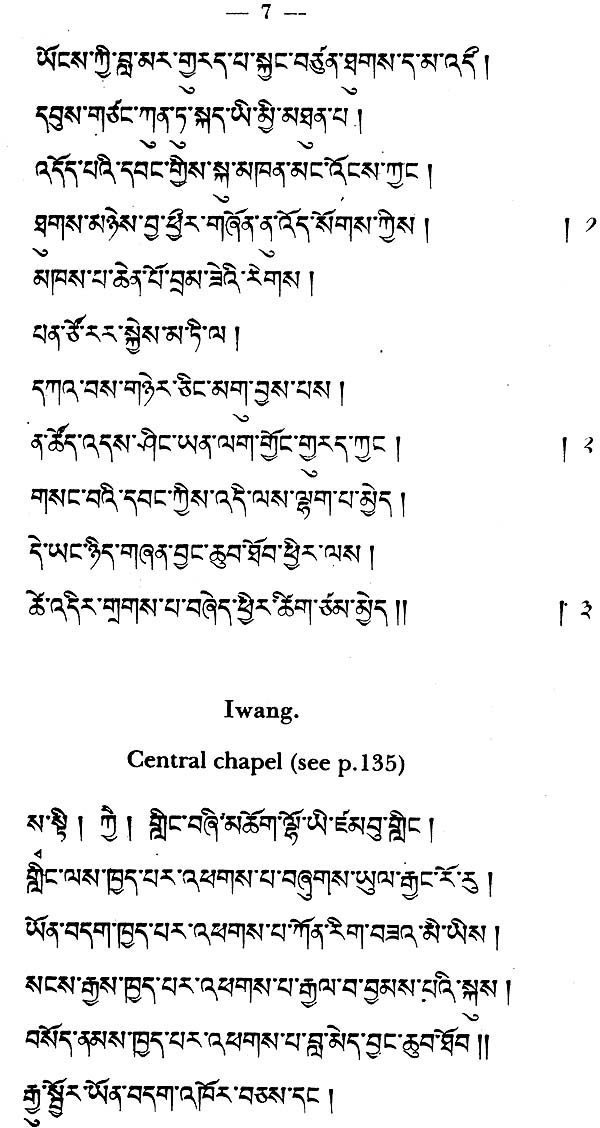

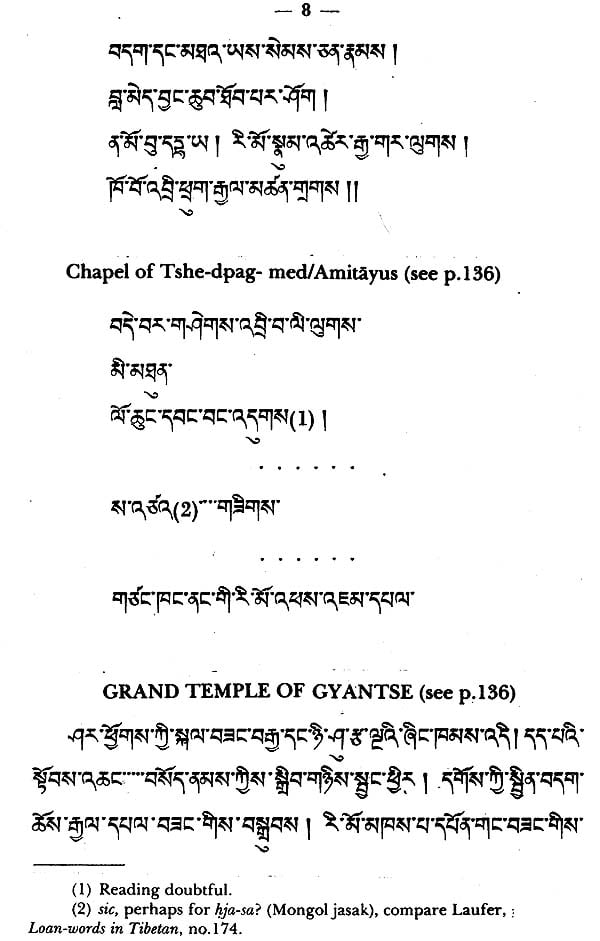

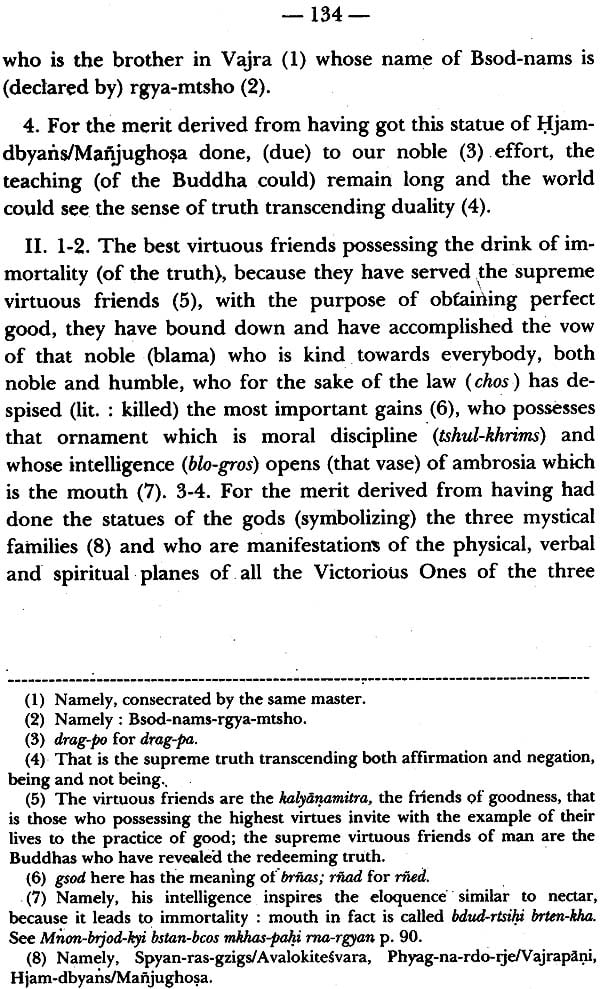

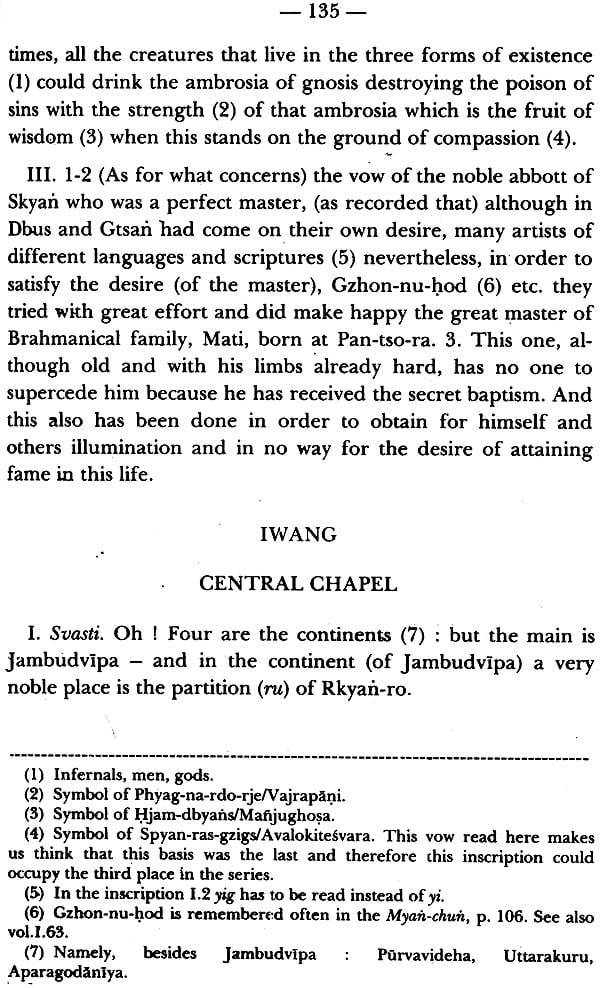

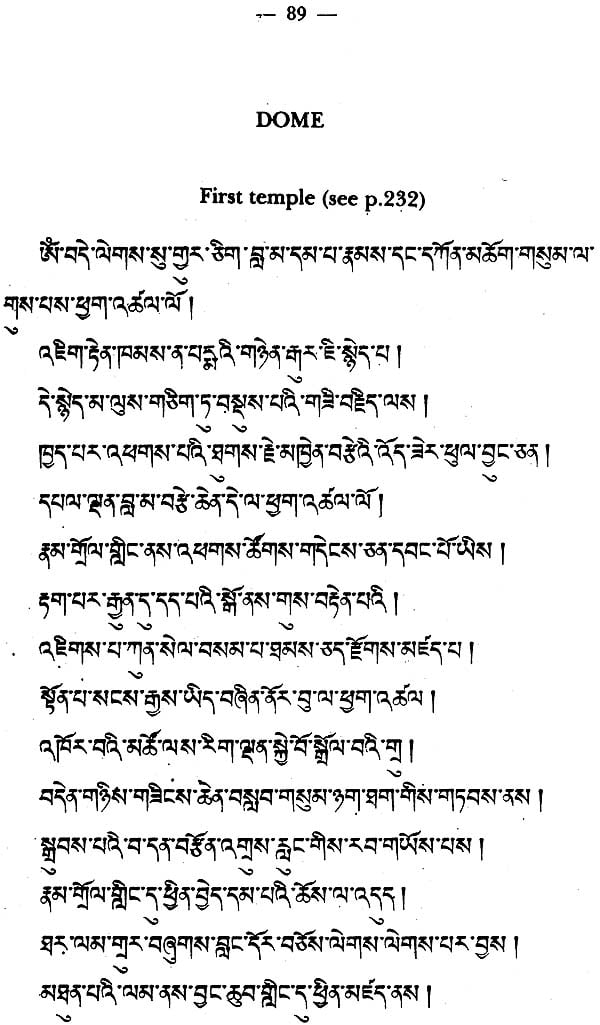

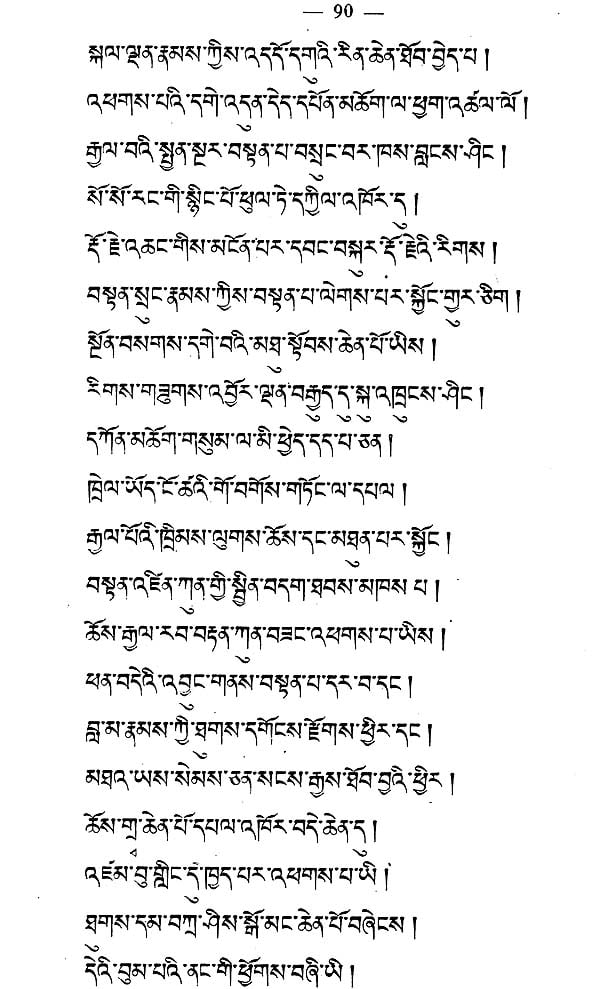

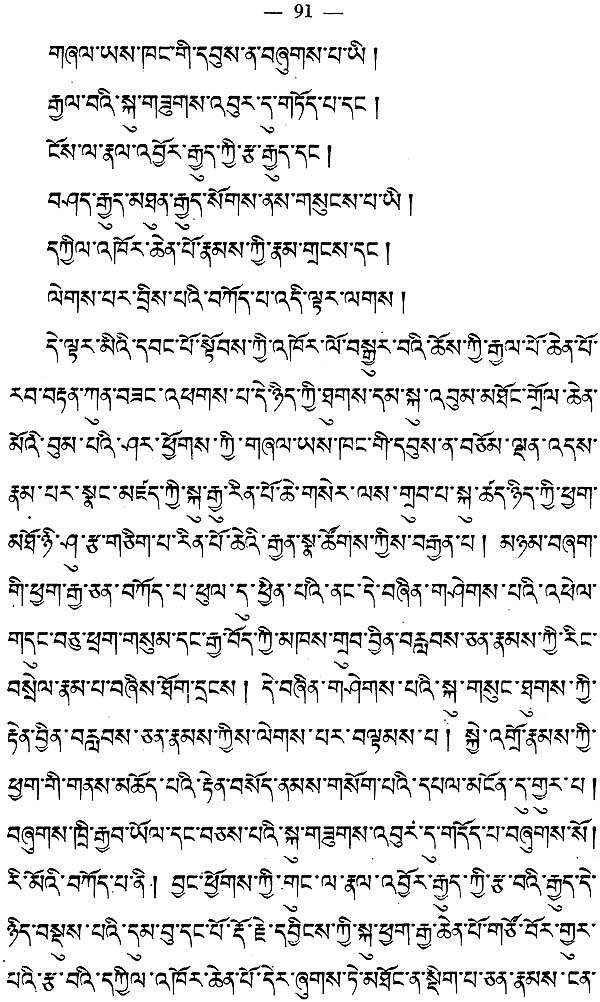

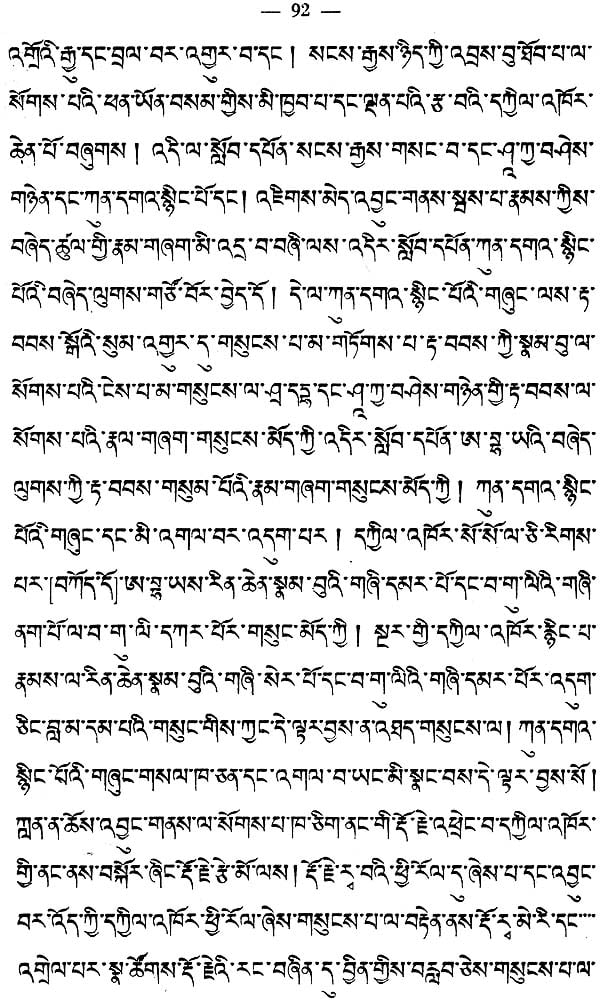

This second part of the fourth volume of Indo-Tibetica. comprises the most important inscriptions found in the monuments studied in the first part. These inscriptions are unique in naming the donors, painters, sculptors who contributed to the adornment of the walls of the chapels and temples with frescoes that mirror the vast pantheon of the Tantric visions in their bewildering variety. These inscriptions enable us to identify each and every divinity in all the richness of its pantheon mandala. This would not have been possible, were there no inscriptions. Prof. Tucci has copied the inscriptions with fidelity, reproducing the orthographic errors and anomalies due to the frequent indifference of the Tibetan copyists. The errors have been pointed out and corrected in the translation of the inscriptions.

The several chapels of the Kumbum which have been described in the first part can be understood with greater precision and in specific details through the translation of the inscriptions. In the translation we have added references to the chapels on the top of every page: thus III.16 means the 16th chapel on the III floor of the Kumbum. This helps to locate the context of every inscription.

The present volume deserves further study as the Tibetan texts are becoming more and more accessible, in translations, and studies, or even in Sanskrit originals, like the Sarva-tathagata-tattva-sangraha which is the most fundamental text of the yogatantras that are crucial to the several systems of Tantras illustrated in the Kumbum murals. The Kumbum is a unique monument of Buddhist art, vying in importance with the Ajanta caves, Kizil, Tun-huang, Yun-kang or Lung-men grottoes, or the Barabudur. It is the last fragrance of the creative grandeur of Buddhism, the glory and silence of time supremely alive. Here is a gallery of frescoes that mirror the diversification of Buddhism. Sakyamuni is transformed from Master into Lord, into an idealised figure. The Enlightened One became the Enlightening One, The Radiator of Light. From Buddha the interest shifted to the abstraction of Buddhahood. From an individual he became a symbol, the science of Buddhahood. Nirvana was transformed into paradise, and karma became modifiable by prayer. Elabo- rate patterns emerged. Buddhism was face 'to face with the Absolute, the Ultimate, the First, the Eternal, the Everlasting and the All-pervading which now was the adamantine purity of the Adi-Buddha. With metaphysical daring this Eternal par excellence, definable by negatives alone, became the bejewelled sambhoga-kaya passionately embracing his transcendant consort or prajna. Extreme serenity was identified with extreme passion, the crystal light with the fire of love, the intangible with all the intoxication of the senses. Sensuality and symbolism, metaphysical filigree of jewels, caresses and cerebrality, earth and sky were, celebrated in proportion and serenity, in portraiture and cryptograms. The murals and sculptures of Kumbum carry these eternal depths to the eyes of the faithful.

Contents

| Preface by Lokesh Chandra | vii |

| | |

| Samada | 5 |

| Iwang | 7 |

| The great temple of gyantse | 8 |

| Sku- hbum/ Kumbum | 9 |

| | |

| Samada | 133 |

| Iwang | 135 |

| The great temple of gyantse | 136 |

| Sku- hbum/ Kumbum | 137 |

| | |

| Some observations on the inscriptions | 275 |

| Military charges | 276 |

| Ecclesiastical charges or offices performed in convents | 277 |

| Craftsmen | 277 |

| | |

| Corrections and additions to Indo-Tibetica, volumnes I-III | 279 |

| The Chronologica system of the Deb-ther snon-po and the chronology adopted in Indo-Tibetica (Note by Dr. Luciano Petech) | 281 |

| Index | 287 |