Islam in History and Politics (Perspeandalctives From South Asia)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAH064 |

| Author: | Asim Roy |

| Publisher: | Oxford University Press, New Delhi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2011 |

| ISBN: | 9780195698367 |

| Pages: | 236 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 240 gm |

Book Description

This timely volume discusses the meanings of Islam, the Muslim community, and the changing nature of Muslim consciousness from colonial to contemporary times in South Asia. The essays explore issues crucial to a holistic understanding of Islam –reform and revival, moral economy, ethnicity, identity formation, pluralism, politics and democracy, and regional manifestations in an insightful Introduction, Asim Roy investigates global and local challenges and the critical problems currently facing Islam and Muslims.

This book will be useful for scholars and students of history, Islamic studies, political scientists, sociologists as well as the general reader.

Asim Roy is Honorary Fellow, School of History and Classics, University of Tasmania, Australia. Formerly he was the Director of the Asia Centre in the same University.

I

For all kinds of reasons, studies in Islam have always been a delicate and contentious matter. This is especially true for those that raise issues in the nature and meanings of the faith in space and time, whether internally from the perspectives of the believers, individually and collectively, or externally from that of the non-believers or outsiders. In the current state of a phenomenal global preoccupation and continual engagement with Islam, there is a resultant feeling of a ‘siege mentality’ shared by almost all over-a-billion strong votaries of the Islamic faith. This makes Islamic studies even more hazardous or perhaps this task may even be set aside as another run-of-the-mill product.

We feel, nonetheless, keen about waving our flag with some justifications. Much of this intellectual exercise associated with the fierce debates and discussions on contemporary Islam, raging for quite some time on a global scale, has been at a level that appears largely uninformed, superficial, and often prejudiced-spawning out sweeping, cavalier, and judgmental opinions. Such interventions confuse and incite people more than they make them informed and understand the issues better, looking at them from alternative perspectives. It has become abundantly clear now even for the most optimists that no amount of bloody hunting and killing of the ‘terrorists’, or forcible ‘regime changes’, or shoving down ‘democracy’ down the throats of distrustful and angry millions by its champions holding guns in their other hands is either going to stop suicide-bombings or make democratic citizens out of those millions any time soon. How many of us are really convinced about the logic and strategy of a ‘final solution’ by killing those who are ready anyway to die and are dying with a smile on their faces? There must be something frightfully missing, in our understanding of such minds as well as in our perception of this desperate and tragic, mother of all crises of modern times. We cannot indeed even begin to get to grips with the problem until we gain a better understanding of its roots. While these conflicts are glibly presented as rooted in historical memory of the Crusades, it is conveniently over-looked that so much of this problem is of modern, and even of recent origins traceable to colonial and postcolonial politics as also social-economic and religious-cultural dislocations, wrongs and discontent. Again, as people turn the focus on the shibboleth of an apocalyptic clash between the Islamic and Western civilizations, popular today as ‘anti-Western jihad’, they seem blissfully oblivious of the fact that since the second wave of Islamism and Islamic revivalist and violent movements in the post-Second World War decades, the thrust of militant anger and resistance was not directed at the West, but at the authoritarian, self serving, and elitist Muslim nationalist leaders of Egypt, Syria, and Iraq.

Informed knowledge and distancing oneself from the half-truths and untruths cooked and dished out from the citadels of power and wealth are the pre-conditions for getting to grips with truth in history. The importance of alternative perspectives seeking to rise above distortions of historical truth is precisely what we have generally brought to bear on, and canvassed for our task in this volume, relative to the complexities of our specific issues and circumstances of Islamic history and politics in the domain of South Asia.

There is a second even more significant consideration underlying our claim in behalf of this volume on South Asian Islam. Facing the most threatening crisis of our time, with real potentials for its indefinite continuation into the future, we strongly feel that the need of the moment is to understand that the problem-almost universally perceived as revolving around Islam and Muslim militancy is really not one between ‘us’ and ‘them’ –it is a common problem not just facing us all, we all bear responsibility for it. An understanding of this nature presupposes one’s preparedness to listen to the other as well as its concomitant value of tolerance. This applies not only to the non-Muslim world vis-à-vis the Muslim, but also to Muslims among themselves.

Had there ever been a reason for re-emphasizing and seeking to recover the genius of Islamic tolerance, adaptability, and creative dynamism in bringing an incredibly diverse Muslim world together-a capacity that is a common knowledge to any student of historical Islam-unquestionably the need for it is far greater now. The general predisposition in the non-Muslim world to see Islam as a monolithic religious culture ruled by the scripture, combined with the present hegemonic challenge of the Islamists, fundamentalists, and jihadis, seeking the rule of ‘sharia’ over all aspects of modern Muslim life have witnessed a very significant heightening of a highly unitary perception of Islam. This development is hardly likely to be helpful for today’s Muslim world that would have a desperate need to come out of it’s siege mentality and meet others for constructive dialogues on an even ground.

The impact of this refurbishing of the notions of unitary Islam has been particularly hard, deleterious, and regressive for the Muslim communities with rich and diverse regional cultural traditions. In the changed circumstances of the Muslim world today, liberal Islam would rather be seeking re-affirmation of its freedom to define Muslims in the way they have understood and accepted Islam. Given the need and the challenge to forge a consensual understanding of the unity and dynamism of Islam within the variety, plurality, and creativity of the Muslim civilization, the relevance, importance, and potential of the Islamic model, as it evolved in history in South Asia, cannot be overestimated. Studies in the general, and more importantly, in the regional settings of South Asia, such as in Bengal, clearly reveal the tradition of tolerance, and creative adaptability of Muslims in South Asia, ‘living together separately’ in the Indic world of unity in diversity. It is about this spirit and tradition of Islamic tolerance and the story of legions of Muslim living for over a millennium in a proverbially diverse plural world of South Asia that the troubled Muslim world of our time, as also the rest of the world, would find strength and hope to hear. While the entire Muslim world has been groping for an answer from their own tradition that the rest of the world is willing to listen, the historic opportunity has been presented to South Asia to step out in front and remind themselves, along with all others, of the glorious tradition of tolerance and accommodation enshrined in the history and politics of the region. The present volume is a symbolic and humble effort on our part to raise South Asia’s consciousness as a paradigmatic example to rise up to this global crisis and challenge. The volume does not necessarily or directly ask or answer all the raging questions about today’s Islam and Muslim. For the discerning readers, however, there are innumerable and invaluable insights into the minds and works of Muslims in South Asia for mapping, probing, and grasping the backdrop of seminal issues and developments through the colonial to postcolonial centuries. Over all, these sources clearly reveal a pattern characteristic of people living together for ages generally peacefully in a plural world with their differences as well as commonalities. These essays together also bring into sharp relief the changing and static meanings of being Muslim in a world that kept changing around them in many areas, but remained unchanged in other respects through a complex process of transition from pre-colonial through colonial to the contemporary states.

II

The essays included in this volume have, with some exception, been the outcome of the first major international symposium on South Asian Islam held in Australia, presented at the forum of the South Asia section of the Asian Studies Association of Australia Biennial Conference, 1996. Organized primarily with the assistance of the professional human and other resources of the South Asian Studies Association of Australia (SASA), it attracted generous sponsorship from the Australia-India Council, the National Centre for South Asian Studies, Melbourne, and the Asian Studies Association of Australia (ASAA). It also attracted a number of leading international scholars in the field –including, in alphabetic order, Javeed Alarm, Paul Brass, Mushirul Hasan, Zoya Hasan, Barbara Metcalf, Thomas R. Metcalf, Gyan Pandey, and Francis Robinson, together with a large local contingent of Australian and New Zealand-based scholars. Over fifteen panels and fifty papers were altogether presented at the symposium, all of which were not included, for various reasons, in their later publication in a Special Issue of the SASA Journal, in accordance with the terms and conditions of the SASA-initiated conferences and symposia.

The far too limited international accessibility of the journal version of a major contribution of its kind led to extensive queries, internationally, from scholars and researchers in the matter of its publication in a book form. I am most thankful to the relevant SASA official, Associate Professor Ian Copland, Editor of South Asia, for having extended his fullest cooperation in this matter and giving me a free hand to find and negotiate with any likely publisher, subject to due acknowledgment of its earlier publication in South Asia. I am also pleased and obliged to the Oxford University Press, New Delhi, for this publication, in particular to Manzar Khan, for his initial interest in the proposal. My deepest and warmest appreciation goes to Shashank Sinha for his infinite patience and understanding of various stages in the preparation of the revamped manuscript and slowing me down. For showing similar patience and consideration at a later stage, Somodatta Roy deserves my highest appreciation. Over all, Oxford University Press has, for me, set up a model of fast-tracking a major publication since the submission of the proposal.

At a very personal level, I do need to express my deepest feelings for my family whom I always found closer as the going got tougher. I should particularly mention my two daughters, Konya and Tanaya, both most brilliant professionals, whose intellectual company and the power of critiquing my research and writing have been as much a source of pride for me as it may easily become a source of envy for any comparable academic parents.

I

One may easily be excused, in the present ambience of global politics, for wanting to turn away from even a mere hint of another intellectual exercise on Islamic history and politics. The world has been deluged in recent times with all kinds of material on Islam and Muslim, churned out relentlessly by the print and visual media, leaving aside the relatively smaller output of authentic academic contributions and an infinite variety and volume of interventions from the so-called 'experts' on Islam and Muslims.' Islam has indeed never been so ubiquitous as it has become in recent years. Its presence is easily found today in every nook and comer of contemporary life-globally, nationally, and 10- cally-dominating the media, academia, polity, economy, and society, including the discourses and deliberations in public places, parks and pubs, and even within individual households around the lounge and dining table.

What is behind this current obsessive preoccupation with Islam? The answers are given and found in legions, but the commonest and the most popular explanation would surely embrace the nine-letter word- 'Terrorism'-a word that creates more confusion than offer real meaning and understanding. Given the unprecedented and kaleidoscopic rise of Islam to the focus of global attention, raising some central issues about Islam in the process, especially since the stunning and tragic event of 11 September 2001 (henceforward 'the 9/11 '), no serious academic intervention in any field of Islamic history and politics- global, regional, or national-can ill-afford to escape these questions. Never before in history has the world cast Islam totally in this manner into a cauldron, heedless of its distinctive features and attributes historically evolved through centuries in its regional settings and formulations. Today's world would need to be persuaded hard to recognize Islam in South Asia, and for that matter in any other non-Western Asian region, as any more than a geographical extension of the so-called Islamic heartland of West Asia.' Historiography of lslam seems to have turned a full cycle. Scholars on South Asian Islam urging an inductive- regional approach have fought tenaciously over a long period to wrest and secure its distinctive form and place from the stranglehold of the Islamists and the champions of monolithic Islam.' The Islamic radicals and their recent western opponents together have knocked off the national boundaries of South Asian Islam by reinforcing the foundation of Islamic monolith. The South Asianists in the Islamic contexts are, therefore, confronted with the same basic questions as their counter- parts everywhere in the Muslim world, and called upon to find their own answers for those. More importantly, South Asia has not been immune from this Islamic upsurge, rather parts of it emerged as an epicentre of militant Islamic movements, as discussed below.

At the core of the popular perceptions, across the world, of this intriguing and explosive situation in recent years there is a strong sense' of Islam being a source as well as an object of challenge and crisis. Such perceptions however, are not new about Islam in history. Muslims in history may perhaps have had more than their rightful share of crises and challenges since the dawn of their history, as Prophet Muhammad was forced to take his incipient group of faithfuls to safety (I A.H [ijira]/ AD 622) from Mecca to Medina, and defend later the growing but fledgling community from the destructive challenges of the non-Muslim. That the rise of Islam was perceived as a threat by medieval Christianity is recorded well in history, and is clearly evidenced by the 'scurrilities of medieval polemic and lampoon' and Muhammad's demonization as a 'false god', a 'false prophet', and a 'cunning and self- seeking impostor'. One widespread medieval legend even presented him as 'an ambitious and frustrated Roman Cardinal', who 'sought an alternative career as a false prophet."

One of the two greatest crises and challenges to confront the Muslim in history has been the non-Muslim Mongol invasion and conquest of a very large part of the Muslim world, extending over central, west, and south Asia, as well as its heartlands, resulting in the fall of Baghdad and the Abbasid Caliphate (AD 1258). This particular threat, potentially very serious, was fortuitously averted, with the wholesale conversion of those conquerors to Islam. The second one, far more powerful and comprehensive than the Mongol invasion, came with the colonial might of the modem west. This challenge was not resolved that easily by conversion and hence remained effectively the first incidence of real subjugation of the Muslim world by the non-Muslim. It is not surprising, therefore, that this encounter has forced Muslim into the myriad experiences of colonial domination and exploitation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and has since continued to encircle and impinge on their lives and culture in various forms.

In recent times, the debacle of the USSR and the consequent elimination of the communist 'threat' to the hegemony of western capitalism, saw the steady emergence of the most serious external challenge to Islam in the resurrection of its old perceived 'threat'. Slowly but steadily, the 'evil' communist Soviet imperial system and ideology found its replacement in an equally 'evil threat' to western values and institutions of democracy, free will, human rights, and so on. It came in the form of an Islamic ideology and movement variously branded, in the western media and political parlance, as Islamic 'fundamental- ism', 'radicalism', 'militancy', 'extremism', 'resurgence', 'Islamism', and 'political Islam'. The spectre of a 'fanatical' and warring Islam sweeping across the world, directly challenging the western political and cultural dominance, often posed as an apocalyptic civilizational conflict, has emerged as a central concern in the post-Soviet west. In the few years immediately following the Soviet disintegration, Khomenian Iran, Palestinian Al-Hamas, Lebanese Hizbullah, Islamic Brotherhood of Egypt, Islamic Salvation Front in Algeria, National Islamic Front of Sudan, Taliban in Afghanistan, Mujahideen of lama 'at- i Islam in Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh and Jumrna Islamiyah of Indonesia, Moros of the Philippines, together with the religiously concerned and sensitive Muslims in many other western and Asian countries, altogether came to create a massive source of 'hype' in the global media and politics. Then came in quick succession, in the new millennium, the daring aggressions' of the Islamic militants spearheaded by A1-Q'aida and other Islamic Jihadis, mounting a series of assaults on western and Asian countries-attacks on the World Trade Centre and rather significantly, on the Pentagon (11 September 2001), the Madrid bombing (March 2004), Bali bombings (October 2002 and September 2(04), the successive bomb explosions targeting the London transport system (July 2005)-all these pulverizing experiences brutally challenged the icon of western power and dominance. With the end of the Cold War, if Francis Fukuyama saw history buried under the rubble of the Berlin Wall and asked us to 'witness' not just the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but 'the end of history' as such, 'the endpoint of mankind's ideological evolution', he is squarely proved short-sighted and wrong within a mere decade or so.

In the wake of this militant aggression, the stereotyping of Islam and Muslims at the global level, together with the unprecedented pressure and indignities brought to bear on this community as a whole under the specious, dubious, and ill-defined label of 'terrorism' have brought about a crisis for the votaries of Islam, the like of which is not found in the past history of Islam. Almost all Western European countries have, it is reported, an 'increasingly popular anti-Muslim platform in their societies,' and Germany, France, Holland, Britain, and Italy have all seen 'a rise in anti-Muslim feeling and incidents in society, as well as in strongly anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant statements by politicians'. For lots of Europeans, who 'associate Muslims with poor, violent ethnic neighborhoods', 'Islam is the cause of the problem', and 'they blame the religion and its adherents not only for social problems at home, but global trends like terrorism.’

It is generally unknown and often overlooked that, prior to the 9/ 11, the general intolerance towards Muslims in the US had reached such a proportion as to call for some Senators as well as Members of the House of Representative to move a Senate as well as a separate House Resolution in 1999 (Senate Resolution 133: 'A Resolution Supporting Religious Tolerance Towards Muslims'). Both Resolutions were referred to their respective Committee on Judiciary. Senate Resolution was passed unanimously in late July 2000. The House Resolution came up to the Subcommittee on the Constitution, but regrettably, it was rejected at the Committee level. A columnist of the Pioneer Planet reported:

several Jewish and Christian groups have been protesting the passage of this resolution. These groups did much behind-the-scene lobbying asking that the resolution be rewritten or removed from the Congressional docket altogether.’

It may be more than a coincidence in measuring the depth and spread of the growing anti-Muslim mentalities in the post-Soviet decades that India saw, in 1992, the stunning destruction of the historic Babri Mosque by the Hindu fanatics, followed, in 2002, by the Gujarat massacre : leading to a mass killing of Muslims by fanatical Hindus, the two most brutal aggressions ever perpetrated on the Muslim minority in India by the saffron-robed champions of militant Hinduism with clear evidence of criminal connivance at the governmental level.

II

If the issue of polarity between the 'secular west' and the 'religion- centred Muslim states and societies' has been simmering for centuries, Bin Laden's stunning intervention on the 9/11 in the name of 'sacred duty' not only gave a violent turn to this debate but sealed as well the question for many. Here was the final proof of a religiously inspired community in action, if any further substantiation was at all required. This position has ready appeal as impeccable for many, and seems right as far as it goes. It puts a rather different gloss to this position to know that the demands or grievances couched in terms of the 'sacred' are patently 'political' for many others. Bin Laden's first telecast of 7 October 2001, after the event of 11 September gave three reasons for the attacks-presence of the US soldiers on the sacred land of Muslims in Arabia, Jewish occupation of Palestinian land, and suppression of the Palestinians, with perceived connivance of the US Government, and finally, the Iraq War.

There is an extraordinary degree of vagueness and confusion about what constitutes the core of Islamism, or Islamic radicalism, or political Islam. Opinions are distinctly polarized between the normative, or essentialist view of religiously inspired action and the 'instrumentalist' perception of socio-politically motivated secular source of apparently religious action. The nature of the problem is clearly underscored by a recent and rather significant shift in the US official attitude in favour not only of replacing the meaningless term 'terrorism', which means all things to all men, but also rejecting identification between the so-called 'terrorism' and 'fundamentalism'. The informed academia has always been dismissive of this facile popular identification of the two. Religious fundamentalism in its accepted sense of a return to and affirmation of the final authority and inerrancy of the scripture or fundamentals of a religion as well as claiming a monopoly over truth, has rarely been a significant component of the radical and militant agenda of political Islam. It is quite suggestive that this equation is now considered inappropriate even in the ranks of US Defence Academy and the CIA, being replaced by terms such as religious 'extremists' and 'radicals'. One wonders as to what extent has the rapidly growing profile of Christian fundamentalism across the US religious-political spectrum been a determinant in this changing attitude.

The current wave of Islamic radicalism defies any simple answer. It is clearly rooted in both religious and secular grounds and is an outcome of both internal and external factors, that is, reasons originating from within the Islamic community and those imposed from outside it. It is important to bear in mind that the dissociation between 'fundamentalism' and 'extremism'I'militancy' made by the US and later adopted by other western governments, is not based on their recognition that the extremist agenda precludes religious purpose and motivation. Both the US and UK governments, on the contrary, have lost no opportunity of condemning the attacks on the western religious, cultural, and political systems and the values informing them. Discerning observers of the so-called 'war on terrorism' since the 9/11 could not have overlooked a general disregard on the part of the governments and media to turn the focus on the clearly articulated 'political' demands consistently put forward by the Mujahideen or Jihadis. We have already raised the relevant issue of Bin Laden's telecast after the event of the 9111, making clear political demands with a religious overtone. This is a fine example indeed of Muslim political demands intersecting with religious concerns. Others however, continue to raise questions. In a strikingly evocative style, Oliver McTernan affirms that none of the responses and reactions to the 9/11 and its fall out 'do justice to the complexity of the growing phenomenon of faith-based violence' and asks:

Who can claim to understand fully the minds and motives of those young, educated and talented men, all of whom spent the last months of their lives meticulously planning the destruction of themselves and thousands of others? Who can claim with certainty that it was grievance, real or imagined, and not their profoundly held religious beliefs that motivated their use of commercial aircraft to commit mass murder....

Drawing together the examples of Mohamed Atta, one of the principal architects of the 9/11, and Richard Reid, the British 'shoe bomber', McTernan drives home his central concern:

These two young men, who came from completely different ethnic & social backgrounds, were united in their readiness to sacrifice their own lives, evidently believing themselves to be on a sacred mission and acting on God's authority.... Given this mindset, I doubt if the world will ever succeed in completely eliminating the threat of the faith-inspired terrorist.

He moves on further to take a position, which appears to contradict his initial guarded stance, as he strongly urges clear recognition that 'religion can be an actor in its own right and should not be dismissed as a surrogate for grievance, protest, greed, or political ambition.'? One can use his own words against his position, 'who can claim with certainty'?

Most people would be naturally inclined, understandably enough, to seek religious meaning and significance in all multi-faceted developments in the Muslim countries, and this has precisely been the case with radical Islamism, which to them is what it says to be-religious in its origins, inspirations, and expressions. It is not for us so much a question of rejecting this popular perception as revealing its inadequacies and simplistic nature. What appears strikingly religious in both form and meaning may not necessarily be essentially religious in inspiration. It is now widely known throughout the Muslim world that Islam is being systematically pressed into secular use by not only Muslim governments, but also people and groups who are opposed to those governments. Many people described a 'fundamentalists' are very far from the actual fundamentals of the religion that they claim to espouse, as noted above. Islam has proved itself a powerful political tool. Religion in South Asia, as perhaps elsewhere, has often been found to conceal secular concerns: transcendental symbols were often, in reality, nothing more than convenient covers for not so elevated mundane interests. One could so easily be misled by the religious symbolism of political Islam. People on the opposite side of the spectrum in this debate, seeking to read exclusively or essentially 'secular' meanings into actions carrying 'Islamic' labels and attributes, are often found to miss out or misread the hidden religious core or the subtle religious implications of a Muslim 'political' action.

Further, there is very little awareness of the inner divergences and complexities in the religious contents of Islamism. The Islamic contents of their agenda are substantially divergent and dissimilar. It is possible to see in all this a broad revivalistic spirit and urge, but no agreement about what is to be revived. The understandings of the pristine 'purity' and 'simplicity' of Islam are not one and the same. There are many different versions of the 'golden age' in Islam. With different groups and interests in Islam, different models and degrees of Islamization have been canvassed, and each ultimately was designed to suit their particular purpose and interest. Hence, the process is often rather 'selective'. Particular matters of shari'a are picked up or ignored to justify matters of specific concerns and interests.

| Preface and Acknowledgements | vii | |

| Introduction | 1 | |

| 1. | Religious Change and the Self in Muslim South Asia since 1800 | 21 |

| 2. | The Composite Culture and its Historiography | 37 |

| 3. | Impact of Islamic Revival and Reform in Colonial Bengal and Bengal Muslim Identity: A Revisit | 47 |

| 4. | Islamic Responses to the Fall of Srirangapattana and the Death of Tipu Sultan (1799) | 88 |

| 5. | South Asian Muslims and the Plague 1896-c. 1914 | 97 |

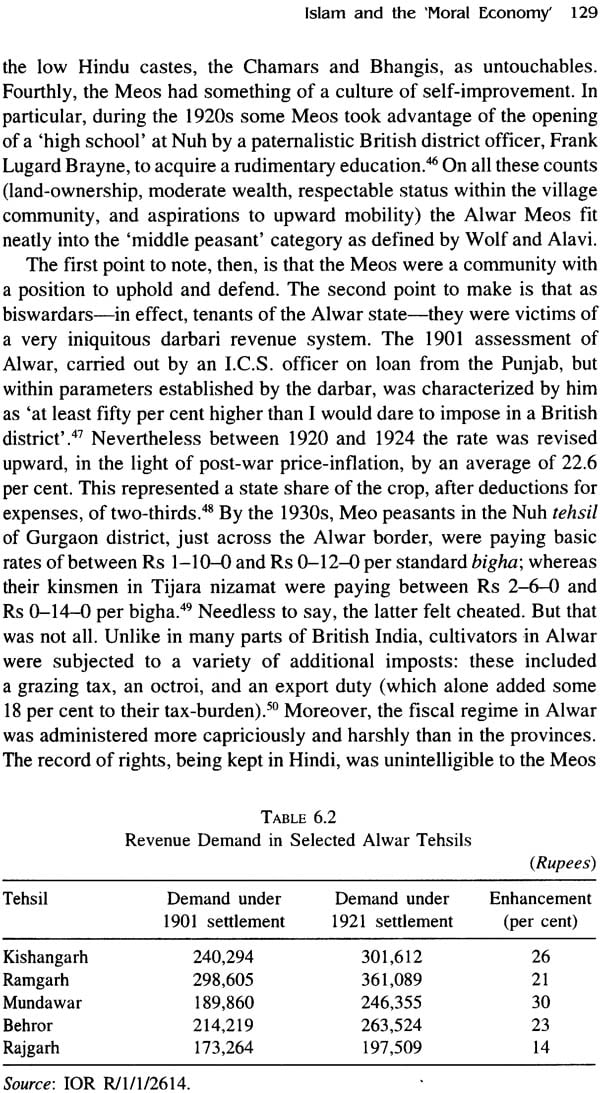

| 6. | Islam and the ‘Moral Economy’: The Alwar Revolt of 1932 | 120 |

| 7. | Coexistence and Communalism: The Shrine of Pirana in Gujarat | 147 |

| 8. | Sikhs and Muslims in the Punjab | 170 |

| 9. | Ethnicity, Islam, and National Identity in Pakistan | 181 |

| 10. | Islamization and Democratization in Pakistan: Implications for Women and Religious Minorities | 198 |

| 11. | Salience of Islam in South Asian Politics: Pakistan and Bangladesh | 212 |

| Contributors | 225 |