The Mahabharata An Inquiry in the Human Condition

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDJ815 |

| Author: | Chaturvedi Badrinath |

| Publisher: | Orient Longman Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2019 |

| ISBN: | 9788125032380 |

| Pages: | 700 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 9.3" X 6.2" |

| Weight | 1 kg |

Book Description

Acknowledgement

My studies in the Mahabharata began systematically in 1971 with the award of a Homi Bhabha Fellowship to me (1971-73), to write on dharma as the key to understanding the history of the Western encounter with Indian civilisation. That encounter took place in the form of Western Christianity, Liberalism, Modern Science and Marxism, each of these forces trying to change India from its own perspective. My journeys in that history showed that each one of them had perceived the foundations of Indian civilisation wrongly. That led me to dharma, upon which those foundations were laid, and dharma led me to the Mahabharata, opening an entirely new universe of the knowledge of the self and of the other in relationship, individually and collectively. My journey changed from studying a history that was limited, anyway mostly negative in being a history of wrong understandings and misunderstandings, to studying the Mahabharata's inquiry into those universal questions of human existence that every human being asks practically at every turn of his or her life.

In writing this work I have come to owe a debt of gratitude to many.

To Jyotirmaya Sharma, most of all. For his unwavering faith in my work on the Mahabharata; reading several chapters of it as they were being written and then the entire text; taking upon himself from the beginning, and that in mist of his own taxing upon himself from the beginning, and that in the midst of his own taxing work, the task of finding a publisher for a book of this size; and form mostly freeing me from the burden of anxieties that arise in the process of having a work of this kind published, taking that burden upon himself instead, and bearing it with patience and grace.

To each of those many institutes and universities, in India and in Europe, who during the last three decades invited me to speak on the various dimensions of dharma in modern contexts or on the Mahabharata as an inquiry in the human condition. Equally to those men and women, in Indian and in Eurpe, with who, at different times, at different places, in different circumstances, I have been having continuing conversations on the Mahabharata's contribution to the knowledge of man and the world. For it is through those conversations that my own understanding of the foundations of relationships, of the self with the self and of the self with the other, deepened. If I do not name those institutes and persons individually here, it is only because their list is long, virtually covering my history of the last three decades of seeking.

To Vishnu Bhagwat, for his abiding faith in this work and its relevance to the India of today; for his continuing concern, even charming impatience, that it be published as early as possible and reach the people. To his wife Niloufer Bhagwat, for setting up, for the women of the diplomatic community in New Delhi, my talk on 'The Women of the Mahabharata' at the Navy House, on 11 March 1998, and for her graciousness to me always. The response of the women of different nationalities assembled at that talk was a Proof that the women of the Mahabharata are universally incarnate as teachers of mankind.

To O.P. Jain; Abdul Rehman Antulay; to Harsh Sethi and to his wife, Vimala Ramachandran; and to Mahesh Buch; for their faith in the relevance of this work and for their support.

To Seeta Badrinath, for her paying the entire expenses of having the Sanskrit shloka-s cited in this book typed into the manuscript.

To Mohini Mullick, for preparing the first draft of the Index and Concordance, in itself considerable work. For its present form and contents, and for any errors (s) in them, the responsibility is mine.

To Punam Kumar, for reading the first eight chapter of the book and suggesting some editorial changes which were very helpful in removing errors and improving at places the text.

To Saradamani Devi, I owe a special debt of deep gratitude.

There are two different Recensions of the Mahabharata, the Southern and the Northern, with different editions in each. In the Southern Recensions, the Kumbakonam edition is best known; in the Northern, the Gita Press Gorakhpur and the Pune editions. The difference between the two Recensions in not only in their size, the Southern omitting in some cases the material that exists in the Northern, and the Northern adding some material that does not exist in the Southern, but also in the numbering of chapters in each of the eighteen parva-s of the Mahabharata, which can vary quite erratically. A substantial part of the present book was written when I lived in Madras (now Chennai) and even though I had 'Gorakhpur' with me then, I had used 'Kumbakonam', all references to chapter and verse being to that edition. The remaining and the major part of it, was written during the last six years in Gurgaon where I lived; all references to chapter and verse now being to 'Gorakhpur', for I didn't have with me Kumbakonam'. To avoid what undoubtedly would have been maddening confusion, and to make the references uniform, I had to change from 'Kumbakonam' to 'Gorakhpur'. That journey turned out to be more painful and draining then I imagined it would be, especially because I could not find 'Kumbakonam' in any of the libraries of Delhi, not even in those where I had hoped I would. For that matter, even in Madras the Kumbakonam edition, out of print for decades, can be seen only in the library of the Kuppuswami Sastri Research Institute.

It was during my maddening journey from 'Kumbakonam' to 'Gorakhpur' (via Gurgaon) that I was led to Saradamani Devi, a Sanskritist. On hearing my tale of woe, she brought out her eighteen volumes of the Mahabharata. They were not 'Kumbakonam' but yet another edition of the Southern recension, the one compiled by P.P.S. Sastri (1935) from the manuscripts at the Tanjore Palace Library (with his variations even in that!). It was clear they would be no help, for the numbering of chapter and verse in them varied from 'Kumbakonam' as much as it did from 'Kumbakonam' to 'Gorakhpur'. Noticing the look of desolation on my face, Saradamani Devi said, 'Even so, take them. They may be of some use to you in your work.' She told me that those books had belonged to her late mother, Ratnamayi Devi, also a Sanskritist. To one totally unknown to her, Saradamani Devi gave away what was to her a family treasure; for her mother would have turned the pages of that edition of the Mahabharata numerous times, leaving upon them the invisible traces of her land. Saradamani Devi's generosity to me could easily be a story from the Mahabharata itself of spontaneous, selfless giving.

To Lance Dane, I owe a debt of gratitude for his passionate support to this work from the moments he read it in manuscript; for his sage counsel as regards the aesthetics of its final production; and for joyfully offering for the cover his photograph of a rare painting depicting Ganesha taking down Vyasa's dictated composition of the Mahabharata, most appropriate for this book, for it begins with the story of Vyasa and his divine stenographer, Ganesha.

And, finally, to Hemlata Shankar of Orient Longman, I owe my profound thanks for the great care and enjoyment she has taken in the editing and production of this book.

Should this work on the Mahabharata be of any value to anyone reading it, and help bring in his or her life the joy of relationships in truth and freedom, my debts of gratitude would have been repaid in some measure of least.

From the Jacket

Chaturvedi Badrinath shows that the Mahabharata is the most systematic inquiry into the human condition. Its principal concern is the relationship of the self with the self and with the other. This book not only proves the universality of the themes explored in the Mahabharata, but also how this great epic provides us with a method to understand the human condition itself.

Badrinath shows that the concerns of the Mahabharata are the concerns of everyday life of dharma, artha, kama and moksha. It is through this everyday-ness, with its complexities as much as with its simplicity, that the Mahabharata still rings true. This book dispels several false claims about what is today known as 'Hinduism' to show us how individual liberty and knowledge, freedom, equality, and the celebration of love, friendship and relationship are integral to the philosophy of the Mahabharata, because they are integral to human life.

Using over 500 shlokas of the original text that he supports with his own lucid translations, Chaturvedi Badrinath's The Mahabharata is an invaluable contribution to our understand of this epic, not in the least, for the elegant scholarship and humanistic approach.

Chaturvedi Badrinath is a philosopher and was born in Mainpuri, Uttar Pradesh. He was a member of the Indian Administrative Service between 1957 and 1989 and spent thirty-one years serving in Tamil Nadu. Badrinath has been Homi Bhabha Fellow (1971-73) and Visiting Professor at Heidelberg University (1971), where he gave a series of seminars on dharma and its application to our times. Giving numerous lectures on Indian thought, he has also been an active participant in inter-religious and inter-civilisational dialogue at various for a across the world.

His other books include Dharma, India and the world Order: Twenty-one Essays (1993) introduction to the Kamasutra (1999); Finding jesus in Dharma; Christianity in India (2000); and Swami Vivekananda: the Living Vedanta (2006).

Badrinath now lives near Pondicherry, India

The cover illustration reproduces an original miniature painting recovered in a small packet of fragment from Indore, Madhya Pradesh. It revealed Lord Ganesha, inscribing the Mahabharata as dictated by Sage Vyasa. The style of he crown and physical mannerisms signify inherent Maharashtrian influence. A few almost intact pages of text suggest a late 18th century Kalam.

Back of the Book

For those generally familiar with the terrain but have now begun to want to get to grips with these concepts because of the sudden upsurge in our contemporary world to go back to 'ancient' truisms this book should be compulsory reading. For both, Chaturvedi Badrinath has provided an excellent introduction to set the stage for how he sees the Mahabharata's methodological avenues unfold the complex and varied conditions of human living.

Aloka Parasher-Sen, The Hindu

18 Chapter about life and living, studied and analysed from several perspectives approaching problems and question through the classic questioning and storytelling method of enquiry. This would not work in another writer's hands, but with Chaturvedi Badrinath, you're on safe territory, since it's pretty obvious that he's spent a good part of his lifetime studying the epic.

First City

Chaturvedi Badrinath has made an eminently commendable effort to produce a compendium of mahavakyas-cum-tika that makes the Mahabharata usable for modern readers The selections and helpful commentary will be a useful starting point for those uninitiated in the text. This digest is by someone who clearly knows the text.

Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Indian Express

| Acknowledgements | ix | |

| A Note on the Diacritical Marks and Translations | xiii | |

| Dramatis Personae of the Mahabharata | xv | |

| The Eighteen Main Parva-s of the Mahabharata | xvii | |

| Chapter 1. | Introduction to the Mahabharata | 1 |

| The subjects of the inquiry and their universality | 3 | |

| The method in the inquiry | 10 | |

| Chapter 2. | Food, Water and life | 23 |

| Food and water in the Upanishad-s | 24 | |

| Food and water in the Mahabharata | 30 | |

| Giving and sharing not ritual 'acts' | 35 | |

| The always-full cooking pot | 37 | |

| A portion for the unknown guest | 39 | |

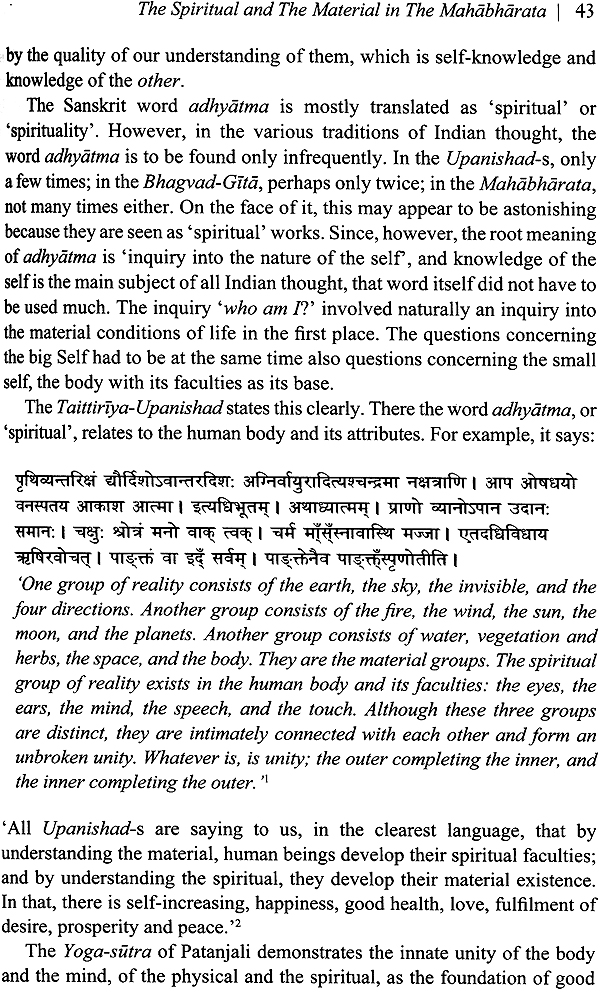

| Chapter 3. | The Spiritual and the Material in the Mahabharata | 41 |

| Perceptions of the Self | 57 | |

| Radical shift in the Mahabharata | 67 | |

| Self, energy, and relationships | 70 | |

| Chapter 3. | Dharma The Foundation of Life and Relationships | 77 |

| The radical shift in the Mahabharata the universality of dharma | 85 | |

| Dharma and the question of relativism | 90 | |

| Another radical shift in the Mahabharata | 95 | |

| Dharma as relationship of the self with the self and with the other | 101 | |

| Chapter 5. | Ahimsa Not violence, the Foundation of Life | 113 |

| Not-violence: The foundation of life of and relationships | 115 | |

| The opposite reality: 'Life lives upon life' | 119 | |

| The rationality of not-violence | 123 | |

| Justification of anger on being wronged | 127 | |

| The rationality of forgiveness and its limits | 142 | |

| The argument against enmity and war | 148 | |

| Violence in speech and words | 154 | |

| Violence to one's Self | 161 | |

| Freedom from fear: freedom from the violence of history | 163 | |

| Chapter 6. | What is 'Death'? The Origin of Mrityu | 169 |

| Chapter 7. | The Question of Truth | 181 |

| Truth and the problem of relativism | 183 | |

| Truth is relational | 192 | |

| Chapter 8. | Human Attributes Neither Neglect, nor Idolatry | 199 |

| Svartha and niti, self-interest and prudence | 216 | |

| Chapter 9. | Human Attributes Sukha and Duhkha : Please and Pain | 225 |

| 'Pleasure' and 'pain': experienced facts | 227 | |

| The reasons why there is more pain than pleasure | 231 | |

| 'Perhaps that is why you look pale and weak'? The psychosomatic link | 239 | |

| From the same facts: three different paths to happiness | 246 | |

| A radical shift in the 'because-therefore' reasoning | 260 | |

| The Mahabharata's teachings of happiness | 263 | |

| Chapter 10. | Material Prosperity and Wealth, Artha | 271 |

| Importance of wealth in the Mahabharata | 273 | |

| The other truth concerning wealth | 280 | |

| Chapter 11. | Sexual Energy and Relationship, Kama and Saha-dharma | 295 |

| Conflicting attitudes towards woman | 304 | |

| Comparative pleasure of man and woman | 312 | |

| The question regarding the primacy of sexuality | 313 | |

| Sexuality and relationship in the Mahabharata | 317 | |

| Possession of the mind | 327 | |

| Kama subject to dharma | 331 | |

| Chapter 12. | Grihastha and grihini, the householder; Grihastha-ashrama, life-in-family | 335 |

| Family as a stage in life | 340 | |

| . | The highest place for the householder and the family | 347 |

| Obligation and duties, and 'the three debts' | 350 | |

| Not obligation and duties alone, also feelings | 351 | |

| The place of the wife in the life-in-family | 354 | |

| The place of the mother in the life-in-family | 360 | |

| Conversations between husband and wife as part of family life | 365 | |

| Life-in-family in the larger context of life | 367 | |

| Chapter 13. | Varna-dharma, Social Arrangements; Loka-samgraha, towards Social Wealth | 369 |

| The origin of varna | 372 | |

| Varna a function, not a person | 375 | |

| By conduct, not by birth | 375 | |

| By birth, not by conduct alone | 379 | |

| The humbling of arrogance | 386 | |

| Antagonism among social function: its psychology | 394 | |

| Harmony among social callings: the way to social wealth | 410 | |

| Chapter 14. | Dharma The Foundation of Raja-Dharma, Law and Governance | 417 |

| The purpose of governance, danda | 422 | |

| The main attribute of governance | 428 | |

| Self-discipline of the king | 430 | |

| Impartiality, truth, and trust in governance | 435 | |

| Trust as the foundation of republics | 440 | |

| Public wealth under the control of dharma | 441 | |

| Fear as the basis of the social order | 444 | |

| Reconciliation or force? | 448 | |

| The law of abnormal times: apad-dharma | 453 | |

| An argument against capital punishment | 455 | |

| The king crates historical conditions, not they him | 458 | |

| Chapter 15. | Sage Narada's Questions to King Yudhishthira | 465 |

| Concerning Yudhishthira's relation with his self | 466 | |

| Concerning the principles of sound statecraft | 468 | |

| Concerning the principles of sound administration | 470 | |

| Questions concerning the security of the realm | 474 | |

| Above all, questions concerning the foundations of good governance | 475 | |

| Chapter 16. | Fate or Human Endeavour? The Questions of Causality | 477 |

| Daiva, fate | 479 | |

| Purushartha: human endeavour | 483 | |

| Endeavour and providence together | 487 | |

| Kala, Time | 491 | |

| Svabhava, innate disposition | 503 | |

| The Question of accountability in what happens | 508 | |

| The Question of causality unresolved | 523 | |

| Beyond 'causality' | 527 | |

| Chapter 17. | From Ritual Acts to Relationships | 529 |

| What is true shaucha, 'purity'? | 530 | |

| What is true tirthas, pilgrimage? | 534 | |

| What is true tyaga, 'renunciation'? | 539 | |

| What is sadachara, 'good conduct'? What is shishtachara, 'cultured conduct'? | 547 | |

| Who is truly a pandita, 'wise'? Who is a fool? | 552 | |

| Who is truly a santa, 'saint'? | 556 | |

| Chapter 18. | Moksha Liberation from the Human Condition | 559 |

| The rationality of moksha | 560 | |

| The radical shift in the Mahabharata | 567 | |

| The attributes of a free person | 570 | |

| Moksha as freedom from | 577 | |

| The paths to moksha | 580 | |

| Moksha as freedom into | 588 | |

| Notes | 593 | |

| Index and Concordance | 631 | |