Political Thought in Sanskrit Kavya

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDJ299 |

| Author: | Geeta Upadhyaya |

| Publisher: | Chaukhambha Orientalia |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1979 |

| Pages: | 432 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.7" X 5.5" |

| Weight | 520 gm |

Book Description

From the Jacket

Ancient Indian Polity is one of the most important subjects described with minute details in Sanskrit literature. There exist scientific treatises on the subject in which its various ramifications have been thoroughly treated and explained. Fresh light is thrown upon the subject by a critical study of the Sanskrit Kavyas written in the glorious period of the Sanskrit Literature. In the present work author has produced a comprehensive and brilliant account of political Thought in the Sanskrit Kavyas belonging to the most creative period of Sanskrit poetry from 1st Cen. B.C. to 12th Cen. A.D. The study has been divided into books; the first deals with pre-kalidasan poets Ashva ghosa and Bhasa; the second with Kalidasa; the third with the Post-Kalidasan Prose writers-Subandhu, Bana Bhatta and Dandin, the fourth with the Post-Kalidasan Dramatists-Sudraka, Bhatta Narayana and Vishakha Datta; the fifth with the Post-Kalidasan Epic writers-Bhatti Bharavi and Magha, and the last with the historical kavya of Raja Tarangina of Kalhana.

Political thought is thought about the state, its structure, nature and its purpose. Sanskrit kavyas reveal that the Vedic political tradition about the state craft was handed down even in the later times when these works were written and they give an ample fund of critical information about the State, its structure and its functioning.

The thesis is well written, fully documented with copious quotations from the Sanskrit Kavyas, Shanti Parva and Kautilya's Arthashastra. For the first time the learned author dives deep into the subject and brings forth sparkling gems of political thoughts embedded in the well-known Epics, Dramas and Prose works of Sanskrit. The book is useful both for the layman and scholars engaged in the study of Political Institutions of Ancient India.

PREFACE

Political thought is thought about the State, its structure, nature and its purpose. Its concern is in no way less than "the moral phenomena of human behavior in society". The purpose of political life is inextricably mixed up with the purpose of life itself. Political theory, it can never convince all, and there has always been fundamental difference over its first principles. "The lines of politics are not the lines of mathematics. They are broad and deep and long". Yet it is unquestionably wrong to say that political thought of ancient civilization has no value, that it is arid, bleak and barren, or that it is useless. To the students of political thought, it is the distilled wisdom of the ages, which one imbibes from its study. Even if it does not lead to the guarantee of assurance in the skill of knowledge about the past, it supplies, at least, prospect of protection against folly.

In the far distant ages of Indian there indeed was expressed thought about man and society, which must be considered as both political and profound. Indian Polity even in early age did not discard democratic element, though analogy to the modern parliamentary form does not hold good in all respects. Coronation Hymns of the Vedas carry reminiscence of recognition that kings are custodian of the sacred trust of the state for the common good, peace and security of the people.

They are to administer the affairs of the state efficiently in order that they may foster and promote the needs and interests of justices and righteousness.

The norms, beliefs and traditions of India's Political thought have been carefully nursed and nourished in the schools of Artha, Niti and Dharmasastra and incidentally in the great Epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. On the basis of the said source material, scholars both Western and Indian have made valuable contributions in the field. Without following the beaten track, I have approached the subject by a different route to catch at the glimpses of political thought the vista of the Classical Kavyas.

The literary productions of masterminds, whether they are expressed in the form of epic, drama or proseromance, are obviously tinctured with the color and traits of social and political environment. They are instinct with traditional of life itself. In the sphere of Sanskrit Kavya curiously enough, there has been artistic presentation of even purely political problems: the notable examples are Bharavi's Kiratarjuniyam and Visakhadatta's Mudraraksasa. The heroes of the classical Kavyas are mostly drawn from the ruling nobility. They represent in them the type of attributes of proper leadership and proper protection, which are indispensable for the rulers of a good state. In some of these writings, we have prototypes of the just and also the efficient Ruler. But in the realm of politics, justness and efficiency are not always necessary correlatives. Politics as a part of ethics is also made up of variables and in the last analysis, justified by exigency of circumstances. The delineation of characters, the movement of the themes and the turn of events in response to political stimuli of diverse grade and significance- these are some of the notable features of political issues that we gather from the Kavyas. The versality of the classical poets is evinced beyond doubt in the matter of politics in both its principles and practice.

We have also noticed in some of these writings reaction of poets mind to politics expressed in either raphsody of praise or in slashing indictments. All these have afforded me fascination date, and my dissertation is a modest attempt at an analytical and critical study of political thought in the light of the Kavyas. The study presented in the following pages seems to be new of its kind in both treatment of facts and their assessment. And how far I have succeeded is left to the discerning judgment of illustrious scholars.

The sources of my information are indicated in the Bibliography and footnotes. The representative texts, monographs and modern critical works have also been utilized to my immense benefit.

As to the plan of the work, I make it a point to mention that the subject has been distributed over nine chapters including Introduction and Conclusion. The standard and typical works of Asvaghosa, Bhasa, Sudraka, Kalidasa, Dandin, Bana, Bhatti, Magha, Bharavi, Bhattanarayanas, Visakhadatta and Kalhana, have been taken up one after another for my study. For comparison I have examined allied political maxims from the source book of Kautilya, Manu, Mahabharata Kamandaka and so fourth. I have made sustained attempt to draw the contours of the political concepts and contents together with questionable axioms on ill-conducted statecraft on the basis of findings of the Kavyas.

In this task my indebtedness to my learned Supervisor Dr. Krishnagopal Goswami, Asutosh Professor and Head of the Department of Sanskrit, Calcutta University, knows no bounds. I must gratefully acknowledge my deep debt to him. It is only because of invaluable assistance and able guidance received from Professor Goswami that I could proceed with the task to complete my work.

I have approached this subject objectively, and I shall deem my labour rewarded if this humble attempt helps in any way in understanding truth of politics clothed in Sanskrit Kavyas.

The importance of a culture lies not only in its power to "raise and enlarge the internal man, mind, the soul and the spirit" but also to shape and modulate his external and social existence to materialise "rhythmic advance" towards high ideals. The ideals of Indian Society upheld the needs of stable social order with prospect of diversity in unity, remarkable richness and interest not only for high intellectual development but also for sound and strong political organisation.

But in order to assess and appreciate the true nature of our Indian Polity, we should not look upon it as detached from the organic whole of the social existence. Politics as a science of discipline has, however, attained singular importance in the hands of the master mind Kautilya, The traditions of Dharmasastra, on the other hand, look upon politics as one of the four-fold ends of life co-ordinated with Dharma (spiritual efficiency) as but a means to an end.

Whatever that may be, the study of Indian Polity and its institutions is admittedly interesting, and scholars both Indian and Western have made their valuable contributions to the field. But they have mostly relied upon the purely political treatises or Dharmasastra texts in their attempts at representing the political theories of ancient India. I have, how- ever, approached the study of the subject in some of its matters of concepts and contents in the light of classical Kavyas. The literary productions of a people, whether they are poetry, drama or prose romances, are by far more valuable and dependable as an objective source of social or political background as reflected therein.

We should also bear in mind that according to the Indian conventions the heroes of the classical Kavyas are mostly chosen from the rank of nobility, generally political rulers who are looked upon as the symbol of strength, vigour and equanimity, and as the sacred trustee of security, peace and protection of the people. The eventful narratives of their life form the themes of ancient and mediaeval Kavyas in Sanskrit. The present writer feels tempted not unwarrantedly to draw the contours of political thought in the light of its findings in the principal Kavyas.

The long line of poets in the realm of Sanskrit literature seek to depict the ideal of Kingship in the character and conduct of rulers whom they delineate. The King's conduct appears to be the focus on which the poet bestows his attention. Both material and spiritual progress of society largely depend upon the right conduct of the king as the protector of the people. The maintenance of the social order and its advancement are the results of good political administration. The ideal character of the king and the principles of kingship as delineated in the classical Kavyas show, on the whole, essential unity of ideas on kingship as handed down from the Vedic to the Epic period. The coro- nation ceremony in the Brahmanic and the Epic period prove beyond doubt the solemn character and democratic responsibility of a person endowed with royal authority. Kingship in the classical literature became almost hereditary, yet the Vedic theory was never forgotten. The observance of the coronation ceremonies and election of Kings on failure of the lines kept the notion of the theory ever green to the mind of the people.

Political institutions, rules of their organisation and their functions, as can be gleaned from the classical Kavyas, more or less bear the semblance of the traditions as worked out in the great epics, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the great works of Manu and Kautilya. Kingship, after all, forms part and parcel of the law of Varnasrama and the poets depict the important aspects of political concepts mostly from that standpoint. Some of these features are summed up below:

(a ) In the four-fold division of caste and duties, the Ksatriyas were normally entrusted with the duty to rule and protect the people. So the king in ancient India generally belonged to the Ksatriya caste, though exceptions are noticeable.

( b ) The King in the Epic age was entrusted with the Executive and Judicial power. But the noteworthy point in this connection is that in spite of his command over all the administrative departments, the king rarely grew despot. For, he had to fear the public opinion which, if unfavourable, was capable enough to create disaffection against him and dethrone him in the long run. The lofty position and towering dignity assigned to the king were only for the benefit of the people. In fact, the king was the custodian of public protection and bound to listen to the public demand. He was not more than a paid servant in the eyes of law and constitution. The one sixth of the products that he got from the people in the form of tax was regarded as his wages for the service rendered to the people.' If he failed in the affairs of administration and did not render security and protection to the people, the people were authorised to claim for the refund of the wages in proportion to their loss." This idea of the wage theory for king's service is a peculiar feature of our ancient Indian polity. It draws our attention to the underlying democratic spirit of Indian monarchy. The king was expected to sacrifice even his personal interests and likings for the sake of his subjects.

( c) The idea of "Cakravartin King" is another salient feature of our ancient Hindu Polity. The king, who ruled the whole sea-girt earth, was called "Cakravartin King" or "Sarvabhauma" (paramount sovereign). The attainment of this status was regarded to be the sacred goal for an ambitious king. Towards this end the ancient kings fought great wars and annexed territories. The instances of warfare as part and programmes of the digvijaya are graphically narrated in Sanskrit Kavyas, Kings aspiring to be the emperor generally performed 'Asvamedha' sacrifice with this political end in-view. In the Satapatha Brahmana it is clearly told. The person who performs the Asvamedha conquers the world. The priest makes him a ruler and up- holder". The sacrificial horse in this sacrifice was let loose to roam over the whole earth, from one end to the other. A large number of attendants and gallant warriors were appointed to look after that horse. The rulers of the countries, through which it passed, were either to surrender or to take hold of the horse as a challenge to fight with the king who was going to perform this sacrifice. If the latter failed to restore the horse by defeating the king who opposed his lord- ship, he could not conclude this sacrifice. On the other hand, if he became successful in extending his sovereignty by and large over the territories of all other kings, he could finalise the sacrifice with great pomp and power. The successful performance of Asvamedha sacrifice was the symbol of the acquisition of paramount sovereignty by the victorious king in order that he may be designated Chakravartin king. So it is told by way of eulogy that "the performer of Asvamedha sacrifice acquires all kingdoms, all peoples, all the Vedas, all the Gods and all created beings"." The Sanskrit Kavyas deal with the life and adventures of several paramount sovereigns as we shall see later.

| Chapter | Pages | |

| I | Introduction | 1-13 |

| PRE-KALIDASA POETS | ||

| II. | Political Thought in Asvaghosa's Buddhacarita and Saundarananda | 17-31 |

| Introductory Remarks | 17 | |

| Kingship and kingly qualities | 17 | |

| Administrative Function of the King | 21 | |

| Political Expedients | 24 | |

| Taxation | 26 | |

| Relation of Politics to Spirituality | 27-29 | |

| III. | Statecraft in Bhasa's Dramas | 32-59 |

| Introductory Remarks | 32 | |

| Kingship | 34 | |

| King's Coronation | 35 | |

| Safeguards of Sovereignty | 37 | |

| Duties of the King | 39 | |

| Deliberation | 41 | |

| Chastisement | 44 | |

| State Undertakings | 45 | |

| Circumstances for a King to remain incognito | 46 | |

| Ministers | 47 | |

| Envoy | 49 | |

| Welfare of the State | 50 | |

| War | 52 | |

| Weapons | 55 | |

| Conclusion | 55-56 | |

| KALIDASA | ||

| IV | Political Concepts in Kalidasa's Works | 60-104 |

| | ||

| Introductory Remarks | 60 | |

| Kingship | 60 | |

| Qualifications of a King-purity of birth | 61 | |

| Strength and Prowess | 62 | |

| Knowledge of Sastras and Control over the Senses | 62 | |

| Trivarga | 63 | |

| Varnasrama Dharma | 67 | |

| Fame | 68 | |

| Charity | 70 | |

| Other Kingly Qualities | 71 | |

| Duties of a King | 73 | |

| Judicial Function of a King | 74 | |

| Undertakings of a King | 75 | |

| Chakravartin King | 76 | |

| Vices of a King | 77 | |

| Taxation | 78 | |

| Secrecy of Deliberation | 78 | |

| Ministers | 78 | |

| System of Espionage | 81 | |

| Place and Power of the Priest | 82 | |

| Warfare | 84 | |

| Diplomacy and War | 86 | |

| Kinds of Kings engaged in Warfare | 87 | |

| Ancient Indian Warfare: A Remarkable feature | 88 | |

| Constituent Elements of the State | 89 | |

| Measures of Foreign Policy | 90-92 | |

| | ||

| King Compared to a sage | 92 | |

| Character of Hindu King | 92 | |

| Sacred Duties of King | 93 | |

| Kingship: a burdensome job | 95 | |

| Taxation | 96 | |

| | ||

| Introductory Remarks | 96 | |

| Treatment of a Neighbour King | 96 | |

| Division of the Country between two claimants | 97-98 | |

| Post-Kalidasa Poetss and Dramalists | ||

| V. | State craft in Prose Kavyas | 105-170 |

| | ||

| Introductory Remarks | 105 | |

| Excellences of a King | 105 | |

| Aspects of Good Administration | 107-109 | |

| | ||

| Introductory Remarks | 110 | |

| Divine character of the king | 110-111 | |

| Qualification of a King | 111 | |

| Good Administration | 112 | |

| Ministers | 114 | |

| Political Maxims of Sukanasopodesa | 116-117 | |

| Need for discipline | 118 | |

| Utility of Guidance | 118 | |

| Condemnation of Laksami | 119-123 | |

| Nature of Power-polluted Kings | 123-125 | |

| Bana Bhatta's Attitude towards Kautilyan Politics | 126-128 | |

| Conduct of King in Foreign Policy and War | 128-129 | |

| | ||

| Introductory Remarks | 129 | |

| Attributes of a Meritorious King | 131 | |

| Relation between King and his Subjects | 133 | |

| Principle of Heredity | 135 | |

| Character of the Office Staff | 136 | |

| Condemnation of Service under King | 137 | |

| Caution against Retaliation | 141 | |

| King and his Ministers | 142 | |

| Warfare-Attack against the Enemy | 143 | |

| Expedition for War | 145 | |

| Elephant Army-twelve Kinds | 146-148 | |

| Superintendent of Elephant Forces | 149 | |

| Idea of a Competent General | 150 | |

| Feudatory Kings | 153 | |

| Secular State | 154-155 | |

| | ||

| Introductory Remarks | 155 | |

| Qualities of Council Minister | 156 | |

| Importance of 'Artha' in Politics | 158 | |

| Proper Conduct for a King | 158 | |

| Some points of Statecraft | 159 | |

| Kingly Qualities | 159-161 | |

| Minister's Advice on Statecraft | 161 | |

| Condemnation of Politics | 162 | |

| Effect of Bad Administration | 166 | |

| Courtier's Conduct | 166-167 | |

| VI. | Post Kalidasa Dramatists | 171-208 |

| | ||

| Introductory Remarks | 171 | |

| Judicial Administration | 173 | |

| Qualification of a Judge | 174 | |

| Legal Procedure | 175 | |

| King as the Supreme Judge | 179 | |

| Punishment for a Brahmana | 180 | |

| Trial by Ordeal | 183 | |

| Crime and Punishment | 185-186 | |

| | ||

| Story of Mudra Raksasa | 187-190 | |

| Triple Administration | 190 | |

| Retaliation against Enemies | 191 | |

| Proper Application of Political Expedients | 193 | |

| Canakya's Diplomacy and Policy | 194 | |

| Secret Agents: Their Selection | 198 | |

| System of Espionage | 197 | |

| Politics and Morality | 199 | |

| King's Duties | 200 | |

| A Politician compared to a Dramatist | 201-202 | |

| | ||

| Introductory Remarks | 202 | |

| Rules and Conditions of Peace and War | 202 | |

| Triple Aim of Life | 203 | |

| Rules of Conduct for Warriors | 204 | |

| The virtue of Self Respect | 208-209 | |

| VII. | Post-Kalidasa Epic Poets | 209-285 |

| | ||

| Introductory Remarks | 209 | |

| When the enemy's growth is negligible | 210 | |

| When one's won decline is negligible | 211 | |

| When to stay inactive | 212 | |

| Peace time measures | 212 | |

| War time measures | 213 | |

| Yana (March) | 215 | |

| Samsraya (Seeking Shelter) | 215 | |

| Asana (Staying quiet) | 216 | |

| Dvaidhi Bhava (Dual Policy) | 217 | |

| Application of Six fold Policies | 217 | |

| Merits and Demerits of Home Policy | 218 | |

| Aims of War | 220 | |

| Drawbacks of an Enemy | 221 | |

| Seducible Parties | 222 | |

| Five-fold aspect of Deliberation | 223 | |

| Excellences of a king | 225 | |

| Duty of a king | 227 | |

| Excellences of a Minister | 227 | |

| Spiritual Power and Temporal Power | 228 | |

| Spy and Envoy | 229 | |

| Political Ideas in Bhatti Kavya | 230-233 | |

| | ||

| Introductory Remark | 234 | |

| System of Espionage | 234 | |

| Pacification of the conqueved territory | 235 | |

| Control of Senses | 237 | |

| Triple Ends of Life | 237-240 | |

| Four Political Expedients | 240 | |

| Encouragement to Agriculture | 243 | |

| Army | 243 | |

| Secretary of Plans and Programmes | 243 | |

| Allegiance of Chiefs and Vassals | 244 | |

| Pleadings for fraud to meet fraud | 245 | |

| Forbearance behooves not a king | 246 | |

| Nature of the Science of Politics | 247 | |

| Four Sciences | 248 | |

| Attitude towards an enemy | 248 | |

| Triple Powers of a king | 250 | |

| Necessity of Cool Deliberation for a king | 251 | |

| Importance of Self-Control | 254 | |

| Importance of forbearance | 255 | |

| Adverse effect of haughtiness | 256 | |

| Attitude of Neutrality | 257 | |

| Two opposite Political views discussed | 257-259 | |

| Superiority of Arms and Army | 260 | |

| Precautions for a warrior | 261 | |

| Ksatriya as a valiant Leader-his duty | 261 | |

| Topic of Alliance | 262 | |

| Vices | 264 | |

| Integrity of the army stressed | 265 | |

| Sense of Self-respect and manly enterprise | 265-266 | |

| | ||

| Introductory Remarks | 266 | |

| Policy and Prospect of war discussed | 267 | |

| Forward policy of Balaram | 267 | |

| Two schools of thought regarding the policy of Ex-pedition | 270-272 | |

| Uddhava's Policy of Deliberation | 272 | |

| Uddhava's Criticism of policy of force and of immediate attack on the enemy advocated by Balarama triumphs | 275-278 | |

| VIII | Statecraft in the Rajatarangini of Kalhana | 286-325 |

| Importance of Rajatarangini as an historical and political document | 286-288 | |

| Kingship: its nature in Kasmir | 288 | |

| Kingship as a sort of trust | 290 | |

| Women occupping royal throne | 291 | |

| Duties of a king | 292 | |

| Administrative functions | 294 | |

| Aspects of good administration | 295 | |

| Nature of Kayasthas in administration | 297 | |

| Measures taken against wicked officers and traitors | 297 | |

| Appointment of Honest Superintendents | 297-298 | |

| Judicial Function of a king | 298 | |

| King as the chief justice of the state | 299 | |

| Method of immediate justice | 300 | |

| King's appreciation for the Learned and the Qualified | 301 | |

| Disqualifications of a king | 302-307 | |

| Evil effects of kingly power | 304 | |

| Avarice and its abuses | 305-306 | |

| Ministers-Qualifications | 308 | |

| Their functions | 310 | |

| Relation between king and his ministers | 310 | |

| Proper conduct for a Royal servant | 311 | |

| Cause of Disaffection of servants | 313 | |

| Cause of Disaffection of the Princes | 314 | |

| State Administration | 314 | |

| Five Important State officials | 315 | |

| Royal Treasury | 316 | |

| Fort | 317 | |

| Texation | 317 | |

| Foreign Policy | 318 | |

| Hunger strike as a powerful Political Weapon | 319-321 | |

| Conclusion | 325-327 | |

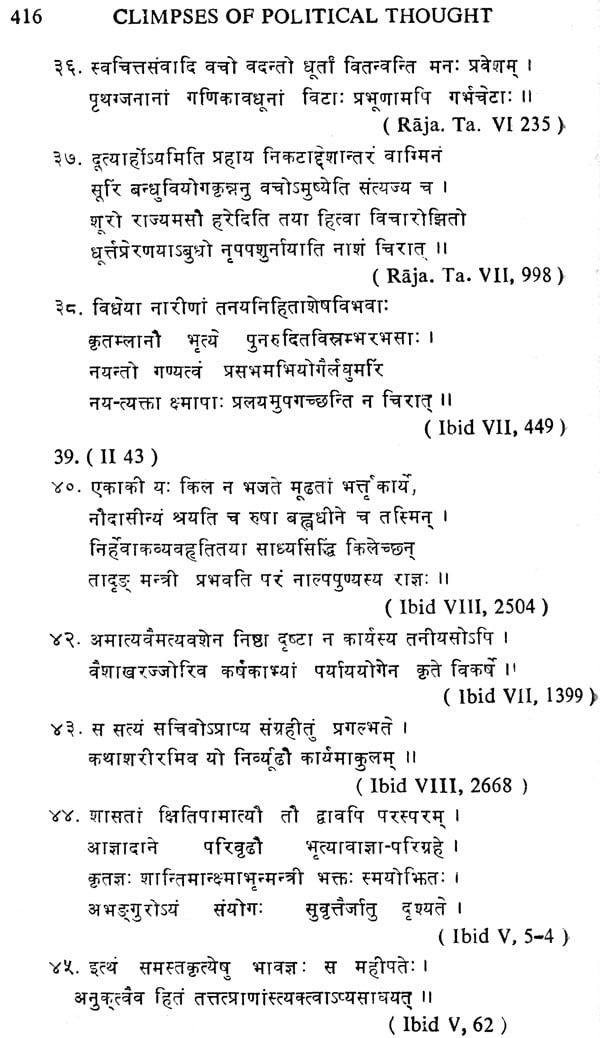

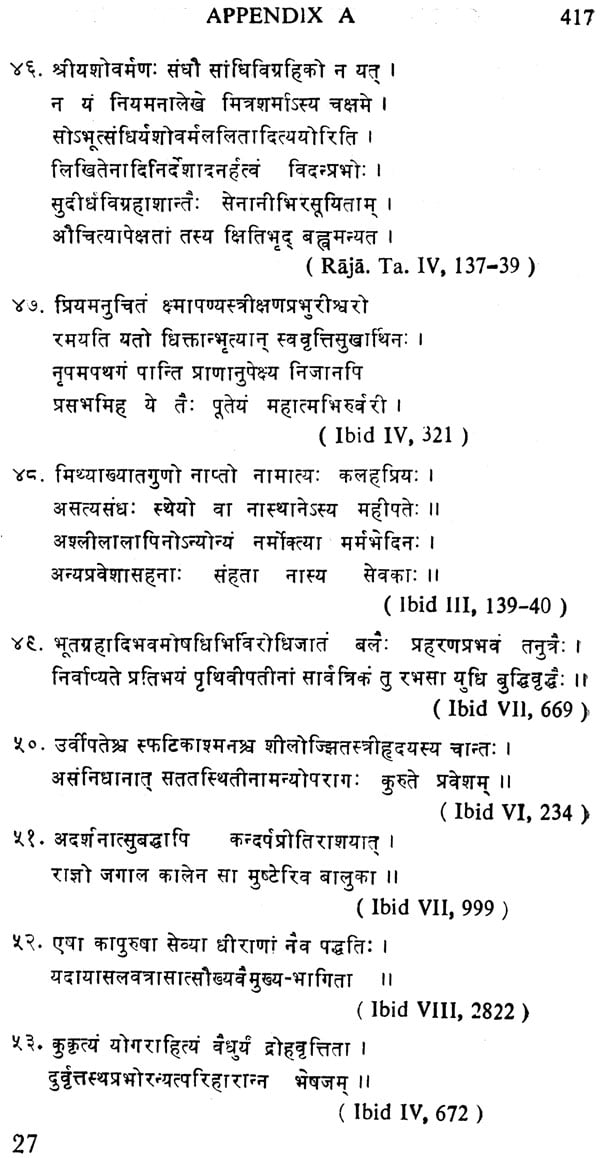

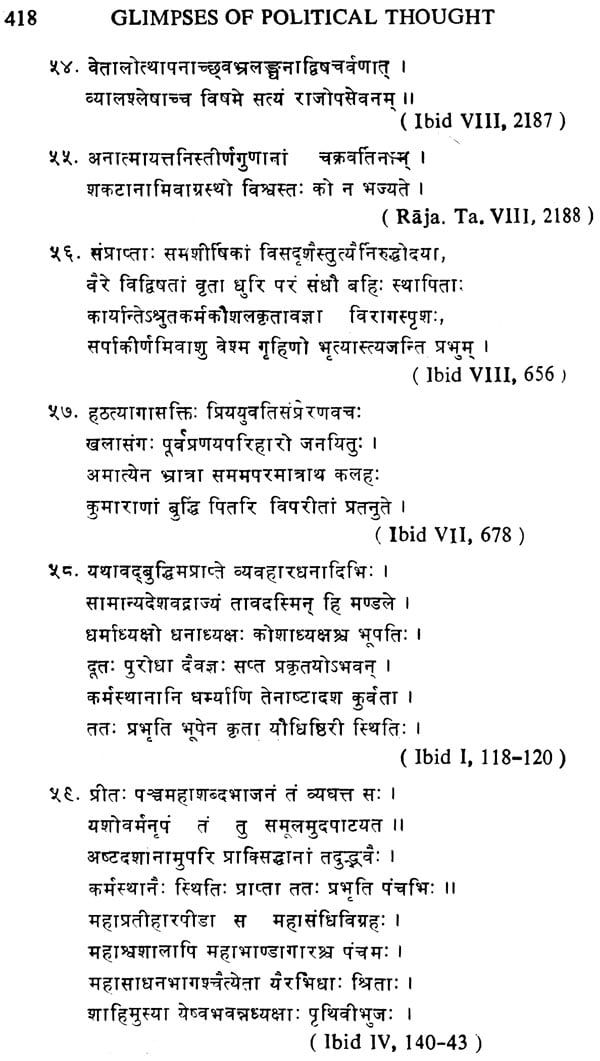

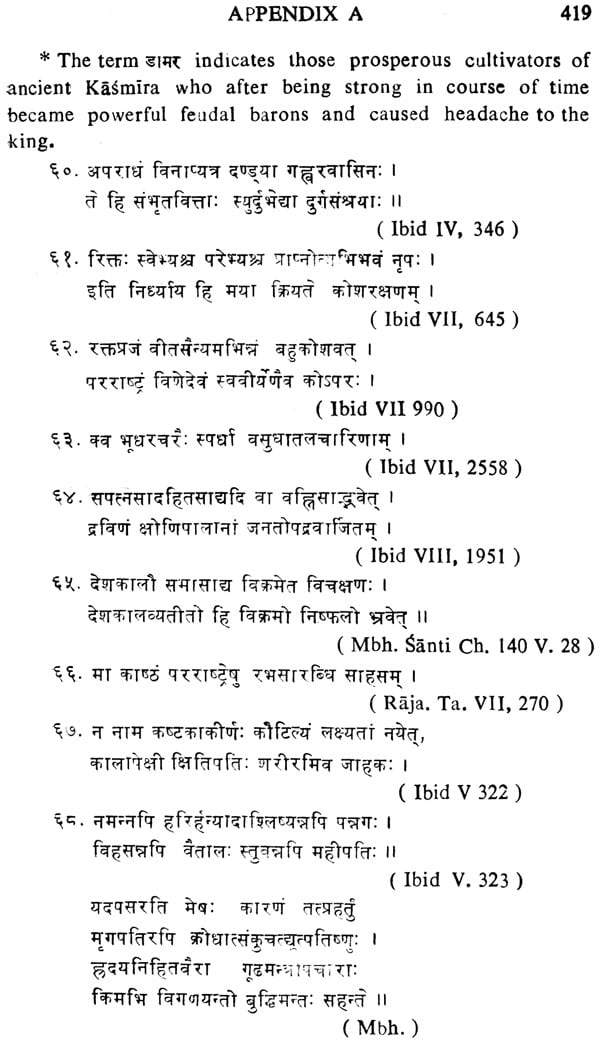

| Appendex A [Textual Authorities indicated by footnotes] | 329 | |

| Book Index | 421 | |

| Author Index | 423 | |

| Subject Index | 425 | |

| Bibliography | 427 | |

| Errata | 431 |