Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged (In Two Volumes)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDK334 |

| Author: | M. Monier Williams, Edited & Revised by Pandit Ishwar Chandra |

| Publisher: | Indica Books, Varanasi |

| Edition: | 2008 |

| ISBN: | 8186569642 |

| Pages: | 1949 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.0" X 8.8" |

Book Description

Editor's Note

The history of Sanskrit dictionary is, perhaps, older than that of the Sanskrit Grammar. It got started with Vedic Concordance named 'Nighantu'. In reality, instead of being a dictionary, Nighantu is more or less a word. During later period, various dictionaries were compiled but, unfortunately, we have lost their original scripts.

Amara Simha's 'Amarakosa' has been considered to be the oldest and most popular compilation. It is also known as Namalinganusasana. in later period, Halayudha-kosa, Vaijayanti-kosa, Mankha-kosa, Nama-mala and Anekartha-samgraha etc. names are worth mentioning.

Two voluminous dictionaries compiled in the 19th century are-Sabdakalpadruma and Vacaspatyam, which stand apart their modern style and technique, Both the volumes are replete with the quotes from the contemporary literature to explain the words convincingly. These, thus may be called a bridge between the dictionary and the encyclopedia.

In present time, Sanskrit English Dictionary of H.H. Wilson, W. Monier and Sanskrit Worterbuch of Oto Bohtlingk's and Sanskrit English Dictionary by Vamana Sivarama Apte and the excellent works in this tradition.

In the tradition of Dictionaries, Sanskrit English Dictionary compiled by Sir Monier Monier-Williams is an important and worth praising work. It's technique of word collection is modern (as the words have been arranged in the alphabetical order, according to the first letter of the word). A major part of it, has been compiled by the chief editor himself after thorough study of the poetic and all other major works in Sanskrit.

As the words of the Sanskrit language have been arranged with their synonyms in English language, such a collection has proved to be a blessing for the readers of English speaking areas. The dictionary of Sir Monier Monier Williams is the most popular and scholarly work of Sanskrit world, equally accepted and appreciated by Indian and Western scholars.

In the present edition, we have replaced the earlier used diacritical notations with their modern equivalents, such as ri with r, ri with r, n with m. Monier Williams employed the symbol '^' for indication of blending of two vowels, but we have used in the present edition, the symbol for the pronunciation of a long vowel as well as for the indication of the blending of two vowels such as a,i,u, and, '^' for just the indication of blending of two vowels, such as o,e,ai,au,etc.

The reference text number of the works indicated, such as 'I' etc. in the earlier edition of Monier Williams has been indicated using the symbol '-' between the two text numbers, such as '0-1' which means the prose matter before the verse number 1 of the text of the said reference work.

The 'Additions and Corrections' portion given at the end of the original edition, has been inserted at appropriate places in the dictionary itself in the present edition. Further, the corrections at the end, has been done in the words itself at the corresponding places.

The present edition is entirely recomposed, enlarged and presented in two volumes in deluxe hard-bound edition, in front of the readers. The idea for its enlargement, revision and re-editing clicked Pandita K.L. Joshi, Proprietor, Parimal Publications, New Delhi, atleast five years ago. He discussed the proposal with me and the present work is a fulfillment of that dream taken together.

I must express my sincere gratitude to every person for any kind of cooperation or assistance in this mission. Further, I welcome any suggestions from the readers about the present edition.

Back of the Book

Sir M. Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary is beyond any doubt the most consulted dictionary in the world of Sanskrit scholarship. Based on the seven volume Sanskrit-German Dictionary of Bohtlingk and Roth it has the enormous advantage of condensing the information contained in that great Sanskrit-German Dictionary. Sir Monier-Williams also went beyond Bohtlingk and Roth and added the meanings of many compounds that were not included in the German Dictionary. He wrote as well many cultural and mythological notes that help in the proper understanding of the Sanskrit terms. The Dictionary is structured along etymological principles, the words being arranged under their roots. This device helps the students to relate words to their original bases giving thereby a deeper insight into the structure of the language. The abundant allusions to cognate indo-European languages and the textual references are an invaluable help in tracing the development of words meanings in the long history of Sanskrit Literature. The present work contains more than 180, 000 words.

Sir M. Monier-Williams was born at Bombay in 1819. He was a disciple of Prof. H.H. Wilson and was awarded the Boden Professor Chair in 1843. He was also the author of an English-Sanskrit Dictionary published in 1851. He established the Indian Institute at Oxford and undertook three journeys to India to successfully complete his Dictionary. He died at Cannes on the 11th April 1899, after devoting more than forty years of his life to Sanskrit Lexicography.

This new edition of Monier-Williams' Sanskrit-English Dictionary has been printed after totally retyping and recomposing the original dictionary, correcting its previous mistakes and greatly improving its clarity.

–

Statement of the circumstances which led to the peculiar System of Sanskrit Lexicography introduced for the first time in the Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary of 1872

To enable me to give a clear account of the gradual development of the plan of the present work, I must go back to its earliest origin, and must reiterate what I stated in the Preface to the first edition, that my predecessor in the Boden Chair, Professor H.H. Wilson, once intended to compile a Sanskrit Dictionary in which all the words in the language were to be scientifically arranged under about 2,000 roots, and that he actually made some progress in carrying out that project. Such a scientific arrangement of the language would, no doubt, have been appreciated to the full by the highest class of scholars. Eventually, however, he found himself debarred from its execution, and commended it to me as a fitting object for the occupation of my spare time during the tenure of my office as Professor of Sanskrit at the old East India College, Hailey bury. Furthermore, he generously made over to me both the beginnings of his new Lexicon and a large MS. volume, containing a copious selection of examples and quotations (made by Pandits at Calcutta under his direction) with which he had intended to enrich his own volume. It was on this account that, as soon as I had completed the English-Sanskrit part of a Dictionary of my own (published in 1851), I readily addressed myself to the work thus committed to me, and actually carried it on for some time between the intervals of other undertakings, until the abolition of the old Hailey bury College on January 1, 1858.

One consideration which led my predecessor to pass on to me his project of a root-arranged Lexicon was that, on being elected to the Boden Chair, he felt that the elaboration of such a work would be incompatible with the practical objects for which the Boden Professorship was founded.

Accordingly he preferred, and I think wisely preferred, to turn his attention to the expansion of the second edition of his first Dictionary- a task the prosecution of which he eventually intrusted to a well-known Sanskrit scholar, the late Professor Goldstucker. Unhappily, that eminent Orientalist was singularly unpractical in some of his ideas, and instead of expanding Wilson's Dictionary, began to convert it into a vast cyclopaedia of Sanskrit learning, including essays and controversial discussions of all kinds. He finished the printing of 480 pages of his own work, which only brought him to the word Arim-dama, when an untimely death cut short his lexicographical labours.

As to my own course, the same consideration which actuated my predecessor operated in my case, when I was elected to fill the Boden Chair in his room in 1860.

I also felt constrained to abandon the theoretically perfect ideal of a wholly root-arranged Dictionary in favour of a more practical performance, compressible within reasonable limits- and more especially as I had long become aware that the great Sanskrit-German Worterbuch of Bohtlingk and Roth was expanding into dimensions which would make it inaccessible to ordinary English students of Sanskrit.

Nevertheless I could not quite renounce an idea which my classical training at Oxford had forcibly impressed upon my mind- viz. that the primary object of a Sanskrit Dictionary should be to exhibit, by a lucid etymological arrangement, the structure of a language which, as most people know, is not only the elder sister of Greek, but the best guide to the structure of Greek, as well as of every other member of the Aryan or Indo-European family- a language, in short, which is the very key-stone of the science of comparative philology. This was in truth the chief factor in determining the plan which, as I now proceed to show, I ultimately carried into execution.

And it will conduce to the making of what I have to say in this connection clearer, if I draw attention at the very threshold to the fact that the Hindus are perhaps the only nation, except the Greeks, who have investigated, independently and in a truly scientific manner, the general laws which govern the evolution of language.

The synthetical process which comes into operation in the working of those laws may be well called samskarana, 'putting together,' by which I mean that every single word in the highest type of language (Called Samskrta) is first evolved out of a primary Dhatu- a Sanskrit term usually translated by 'Root,' but applicable to any primordial constituent substance, whether of words or rocks, or living organisms- and then, being so evolved, goes through a process of 'putting together' by the combination of other elementary constituents.

Furthermore, the process of 'putting together' implies, of course, the possibility of a converse process of vyakarana, by which I mean 'undoing' or 'decomposition;' that is to say, the resolution of every root-evolved word into its component elements. So that in endeavouring to exhibit these processes of synthesis and analysis, we appear to be engaged, like a chemist, in combining elementary substances into solid forms, and again in resolving these forms into their constituent ingredients.

It seemed to me, therefore, that in deciding upon the system of lexicography best calculated to elucidate the laws of root-evolution, with all the resulting processes of verbal synthesis and analysis, which constitute so marked an idiosyncrasy of the Sanskrit language, it was important to keep prominently in view the peculiar character of a Sanskrit root- a peculiarity traceable through the whole family of so-called Aryan languages connected with Sanskrit, and separating them by a sharp line of demarcation from the other great speech-family usually called Semitic.

And here, if I am asked a question as to what languages are to be included under the name Aryan- a question which ought certainly to be answered in limine, inasmuch as this Dictionary, when first published in 1872, was the first work of the kind, put forth by any English scholar, which attempted to introduce comparisons between the principal members of the Aryan family- I reply that the Aryan languages (of which Sanskrit is the eldest sister, and English one of the youngest) proceeded from a common but nameless and unknown parent, whose very home somewhere in Central Asia cannot be fixed with absolute certainty, though the locality may conjecturally be placed somewhere in the region of Bactria (Balkh) and Sogdiana, or not far from Bokhara and the first course of the river Oxus. From this centre radiated, as it were, eight principal lines of speech- each taking it own course and expanding in its own way- namely the two Asiatic lines: (A) the Indian- comprising Sanskrit, the various ancient Prakrts, including the Prakrt of the Inscriptions, the Pali is of the Buddhist sacred Canon, the Ardha-Magadhi of the Jains, and the modern Prakrts or vernacular languages of the Hindus, such as Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, Bengali, Oriya etc. (B) the Iranian- comprising the Avesta language commonly called Zand or Zend, old Persian or Akhaemenian, Pahlavi, modern Persian, and, in connection with these, Armenian and Pustu; and then the six European lines: (A) Keltic, (B) Hellenic, (C) Italic, (D) Teutonic, (E) Slavonic, (F) Lithuanian, each branching into various sub-lines as exhibited in the present languages of Europe. It is this Asiatic and European ramification of the Aryan languages which has led to their being called Indo-European.

Now if I am asked a second question, as to what most striking feature distinguishes all these languages from the Semitic, my answer is, that the main distinction lies in the character of their roots or radical sounds; for although both Aryan and Semitic forms of speech are called 'inflective,' it should be well understood that the inflectiveness of the root in the two cases implies two very different processes.

For example, an Arabic root is generally a kind of hard tri-consonantal framework consisting of three consonants which resemble three sliding but unchangeable upright limbs, moveable backwards and forwards to admit on either side certain equally unchangeable ancillary letters used in forming a long chain of derivative words. These intervenient and subservient letters are of the utmost importance for the diverse colouring of the radical idea, and the perfect precision of their operation is noteworthy, but their presence within and without the rigid frame of the root is, so to speak, almost overpowered by the ever prominent and changeless consonantal skeleton. In illustration of this we may take the Arabic tri-consonantal root KTB, 'to write,' using capitals for the three radical consonants to indicate their unchangeableness; the third pers. sing. past tense is KaTaBa, 'he wrote,' and from the same three consonants, by means of certain servile letters, are evolved with fixed and rigid regularity a long line of derivative forms, of which the following are specimens:- KaTB, and KiTaBat, the act of writing; KaTiB, a writer; maKTuB, written; taKTiB, a teaching to write; muKaTaBat, and taKaTuB, the act of writing to one another; mutaKaTiB, one engaged in mutual correspondence; iKTaB, the act of dictating; maKTaB, the place of writing, a writing-school; KiTaB, a book; KiTBat, the act of transcribing.

In contradistinction to this, a Sanskrit root is generally a single monosyllable, consisting of one or more consonants combined with a vowel, or sometimes of a single vowel only. This monosyllabic radical has not the same cast-iron rigidity of character as the Arabic tri-consonantal root before described. True, it has usually one fixed and unchangeable initial letter, but in its general character it may rather be compared to a malleable substance, capable of being beaten out or moulded into countless ever-variable forms, and often in such a way as to entail the loss of one or other of the original radical letters; new forms being, as it were, beaten out of the primitive monosyllabic ore, and these forms again expanded by affixes and suffixes, and these again by other affixes and suffixes, while every so expanded form may be again augmented by prepositions and again by compositions with other words and again by compounds of compounds till an almost interminable chain of derivatives is evolved. And this peculiar expansibility arises partly from the circumstance that the vowel is recognized as an independent constituent of every Sanskrit radical, constituting a part of its very essence or even sometimes standing alone as itself the only root.

Take, for example, such a root as Bhu, 'to be' or 'to exist.' From this is, so to speak, beaten out an immense chain of derivatives of which the following are a few examples:- Bhava or Bhavana, being; Bhava, existence; Bhavana, causing to be; Bhavin, existing; Bhuvana, the world; Bhu or Bhumi, the earth; Bhu-dhara, earth- supporter, a mountain; Bhu-dhara-ja, mountain-born, a tree; Bhu-pa, an earth-protector, king; Bhupa-putra, a king's son, prince, etc. etc.; Ud-bhu, to rise up; Praty-a-bhu, to be near at hand; Prodbhuta, come forth, etc.

Sanskrit, then, the faithful guardian of old Indo-European forms, exhibits these remarkable properties better than any other member of the Aryan line of speech and the crucial question to be decided was, how to arrange the plan of my Dictionary in such a way as to make them most easily apprehensible.

On the one hand I had to bear in mind that, supposing the whole Sanskrit language to be referable to about 2,000 roots or parent-stems, the plan of taking root by root and writing, as it were, the biographies of two thousand parents with sub-biographies of their numerous descendants in the order of their growth and evolution, would be to give reality to a beautiful philological dream- a dream, however, which could not receive practical shape without raising the Lexicon to a level of scientific perfection unsuited to the needs of ordinary students.

On the other hand I had to reflect that to compile a Sanskrit Dictionary according to the usual plan of treating each word as a separate and independent entity, requiring separate and independent explanation, would certainly fail to give a satisfactory conception of the structure of such a language as Sanskrit, and of its characteristic processes of synthesis and analysis, and of its importance in throwing light on the structure of the whole Indo- European family of which it is the oldest surviving member.

I therefore came to the conclusion that the best solution of the difficulty lay in some middle course- some compromise by virtue of which the two lexicographical methods might be, as it were, interwoven.

It remains for me to explain the exact nature of this compromise and I feel confident that the plan of the present work will be easily understood by any one who, before using the Dictionary, prepares the way by devoting a little time to a preliminary study of the explanations which I now proceed to give.

Explanation of the Plan and Arrangement of the Work and of the Improvements introduced into the Present Edition

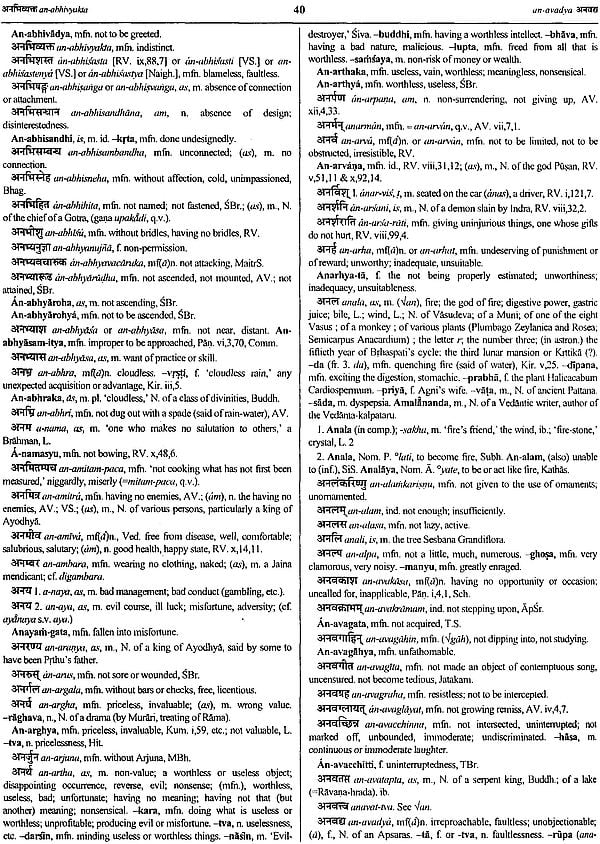

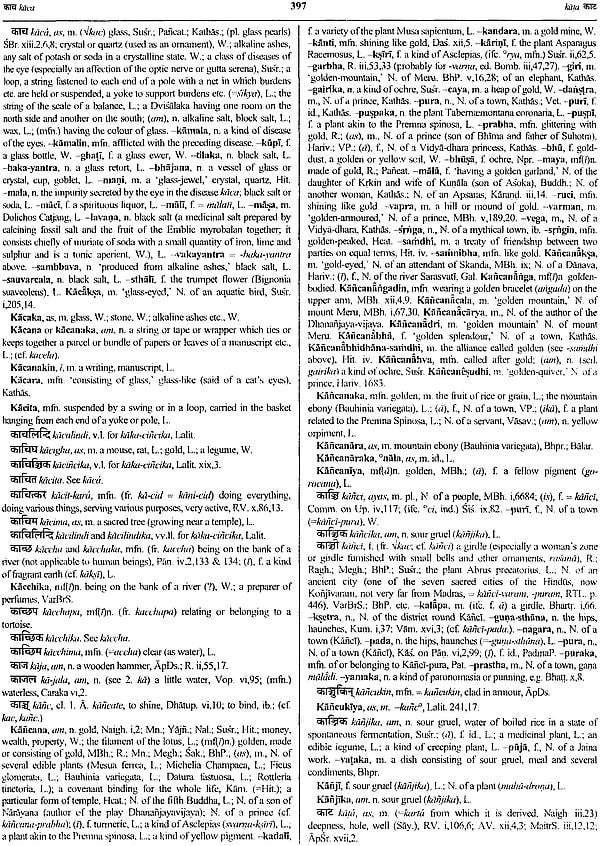

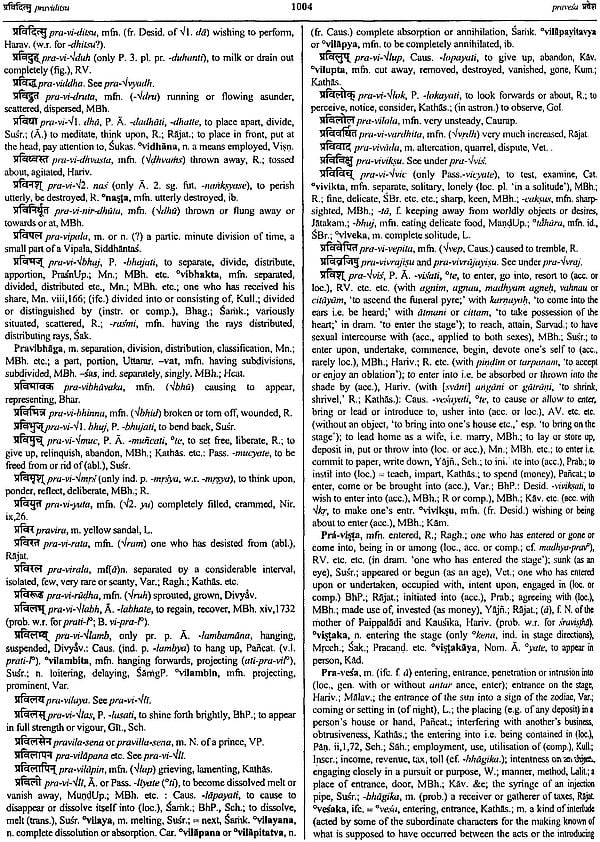

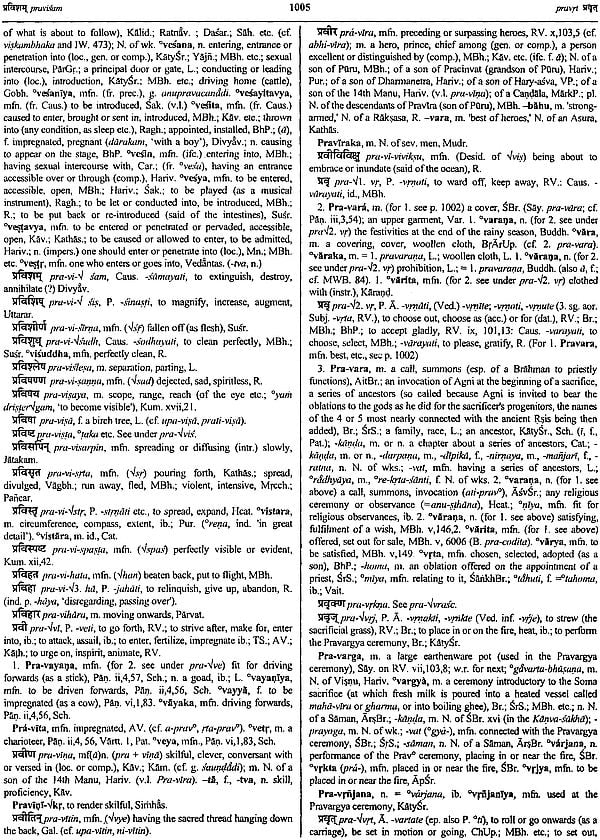

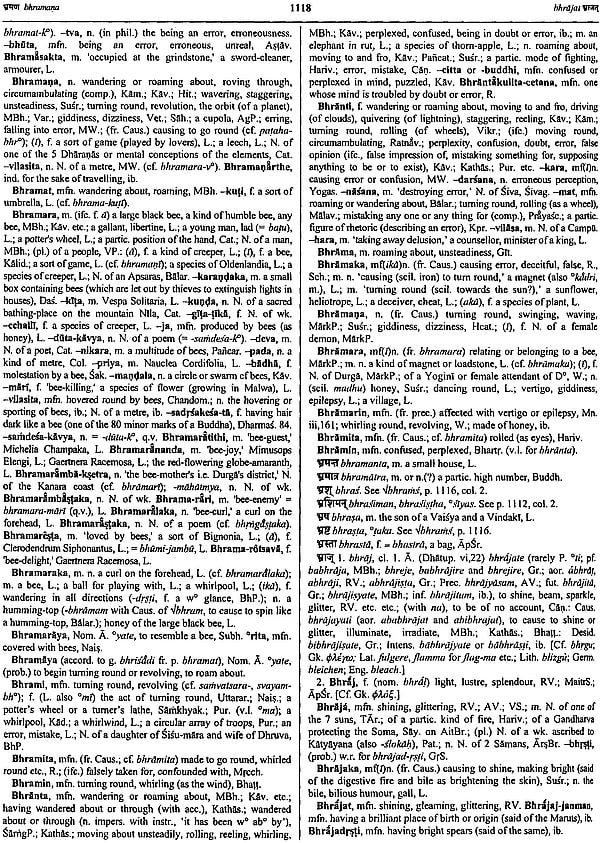

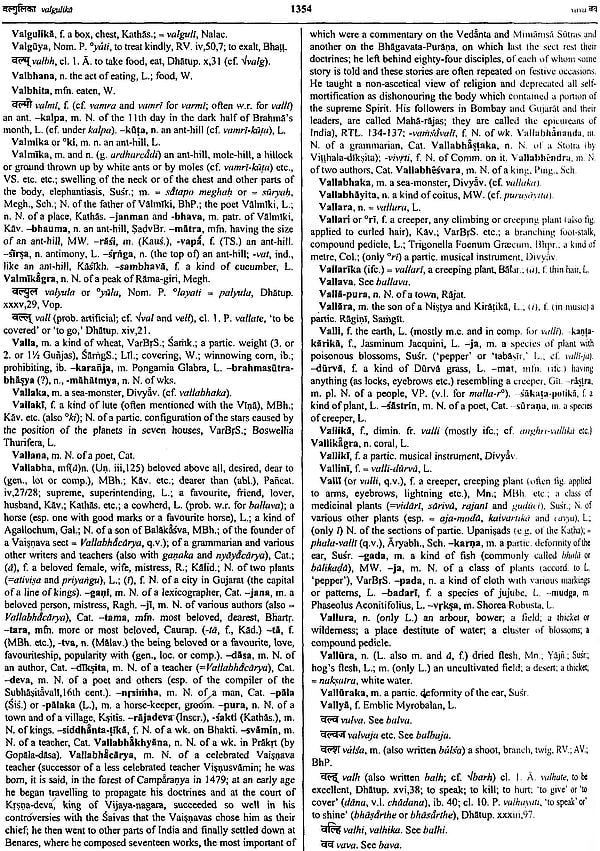

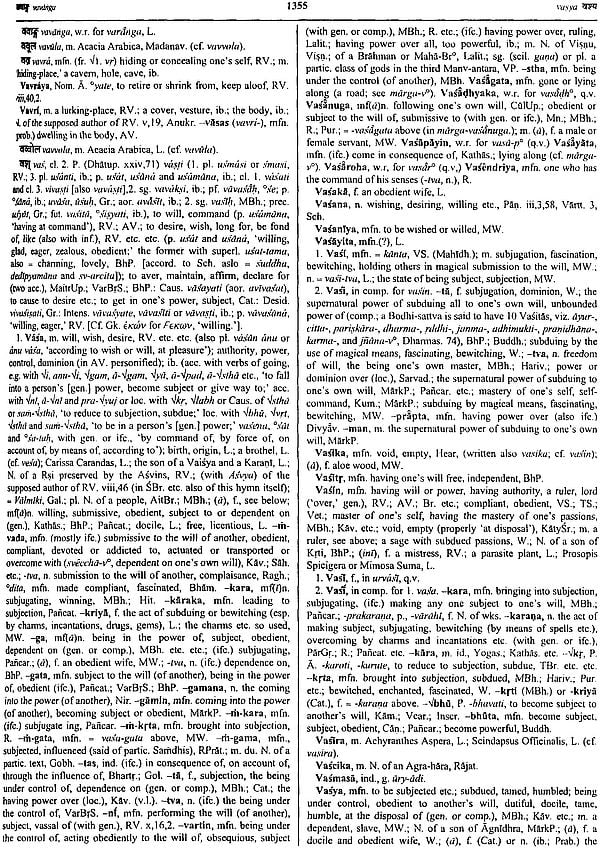

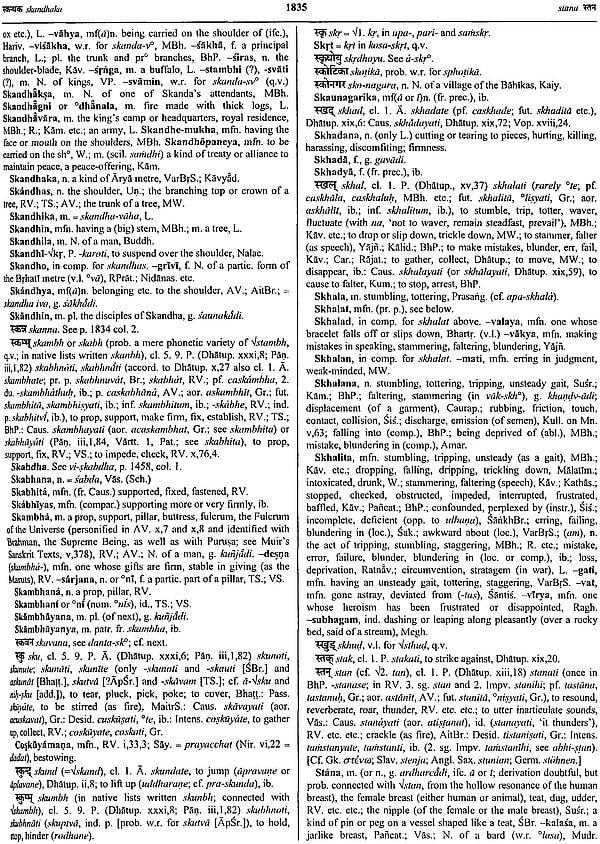

Be it notified, at the very threshold, that there are four mutually correlated lines of Sanskrit words in this Dictionary:- (l) a main line in Nagari type, with equivalents in Indo-Italic type; (2) a subordinate line (under the Nagari) in thick Indo-Romanic type; (3) a branch line, also in thick Indo-Romanic type, branching off from either the first or the second lines with the object of grouping compound words under one head; (4) a branch line in Indo-Italic type, branching off from leading compounds with the object of grouping together the compounds of those compounds. Of course all four lines follow the usual Sanskrit Dictionary order of the alphabet (see p. xxxix).

The first or main line, or, as it may be called, the 'Nagari line,' constitutes the principal series of Sanskrit words to which the eye must first turn on consulting the Dictionary. It comprises all the roots of the language, both genuine and artificial (the genuine being in large Nagari type), as well as many leading words, in small Nagari, and many isolated words (also in small Nagari), some of which have their etymologies given in parentheses, while others have their derivation indicated by hyphens.

The second or subordinate line in thick Indo-Romanic type is used for two purposes:- (a) for exhibiting clearly to the eye in regular sequence under every root the continuous series of derivative words which grow out of each root; (b) for exhibiting those series of cognate words which, to promote facility of reference, are placed under certain leading words (in small Nagari) rather than under the roots themselves.

The third or branch line in thick Indo-Romanic type is used for grouping together under a leading word all the words compounded with that leading word.

The fourth or branch Indo-Italic line is used for grouping under a leading compound all the words compounded with that compound.

The first requires no illustration; the second is illustrated by the series of words under कृ 1. kr (p. 442) beginning with 1. Krt, p.443, col. 1 and under 1. kara (p. 376) beginning with 1. Karaka (p. 377, col. 1); the third by the series of compounds under 1. kara (p. 376, col. 1) and Karana (p. 377, col. 1); the fourth by the series of compounds under- vira (p. 376).

And this fourfold arrangement is not likely to be found embarrassing; because anyone using the Dictionary will soon perceive that the four lines or series of Sanskrit words, although following their own alphabetical order, are made to fit into each other without confusion by frequent backward and forward cross-references. In fact, it will be seen at a glance that the ruling aim of the whole arrangement is to exhibit, in the clearest manner, first the evolution of words from roots, and then the interconnection of groups of words so evolved, as members of one family descended from a common source. Hence all the genuine roots of the language are brought prominently before the eye by large Nagari type; while the evolution of words from these roots, as from parent-stocks, is indicated by their being printed in thick Romanic type, and placed in regular succession either under the roots, or under some leading word connected with the same family by the tie of a common origin. It will be seen, too, that in the case of such leading words (which are always in Nagari type), their etymology- given in a parenthesis- applies to the whole family of cognate words placed under them, until a new series of words is introduced by a new root or new leading-word in Nagari type. In this way all repetition of etymologies is avoided, and the Nagari type is made to serve a very useful purpose.