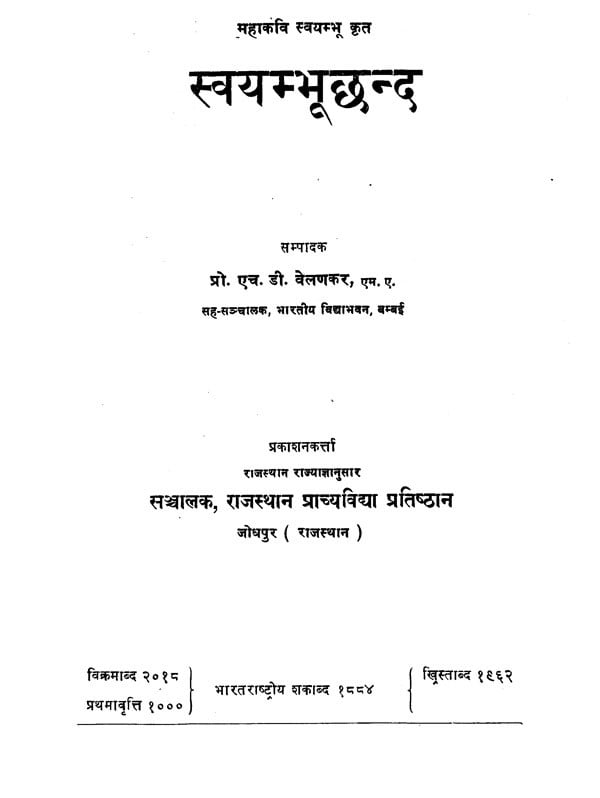

स्वयम्भूछन्द- Svayambhuchhanda of Mahakavi Svayambhu (An Old and Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | TZZ713 |

| Author: | H. D. Velankar |

| Publisher: | Rajasthan Oriental Research Institute, Jodhpur |

| Language: | Hindi and English |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| Pages: | 248 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.50 X 6.50 inches |

| Weight | 440 gm |

Book Description

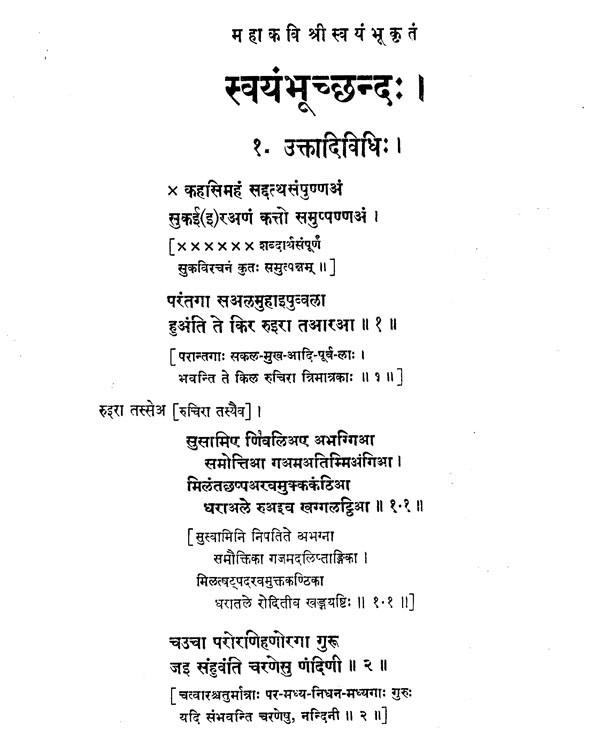

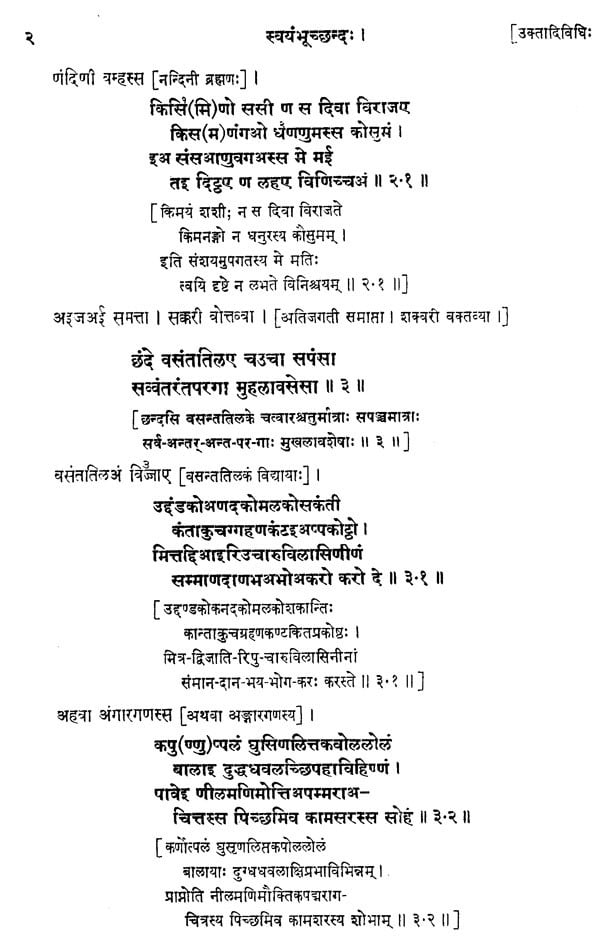

It is a matter of great pleasure for me that the Rajasthan Puratana Granthamala publishes here with as its No. 37 Svayambhu's important manual of Prakrit and Apabhramsa metres, called Svayambhucchandas. Systematic accounts of Sanskrit and Prakrit-Apabhramsa prosodies reached their culmination in Hemacandra's Chandonusasana. The Svayambhucchandas was one of the basic sources of the latter. Hemacandra's arrangement, classification and illustrations of metres owe much to Svayambhu.

But the importance of the present work is not confined merely to the fact that it was a two hundred and fifty years senior ancestor of the famous Chandonusasana. The Svayambhucchandas is unique in several other ways too. Firstly, Svayambhu himself was a Kaviraja-a front rank poet with several voluminous epics of acknowledged merit to his credit. The literary worth of one published work of Svayambhu viz, Paumacariu (edited by my beloved pupil and learned colleague, Dr. H. C. Bhayani, a profound scholar of Apabhramsa and allied literature and published by me in 1953 and 196o in three volumes in the Singhi Jain Series) is ample enough to establish it as a high water mark of Apabhramsa poetry. Svayambhu's account of metres, therefore, bears that stamp of authority of a practising artist, which the work of a mere theoretician would lack. And some of the illustrations in the Svayambhucchandas are in fact taken from the Paumacariu (vide Appendix III, pp. 241-242 of the present volume.) Secondly, unlike Hemacandra who has composed his own illustrations, Svayambhu has drawn upon more than eighty earlier (or contemporary) Prakrit and Apabhramsa authors to illustrate his metrical definitions. This fact by itself is enough to make the Svayambhucchandas highly authoritative.

Incidentally, however, so many citations of greatly varying form and content from divergent sources give us for the first time (if we exclude the stray lyric anthologies, with their near-worthless ascriptions) names of a host of authors who, over centuries preceding Svayambhu, were responsible for cultivating an abundant and rich literature in Prakrit and Apabhramsa. Though about most of these names we know nothing more, they are strong evidence of a respectable and vigorous literary tradition. This is again more than confirmed by the aesthetic appeal and freshness that invest many of the cited verses. It is again from the Svayambhucchandas, that we get a clearer picture of the form and structure of Sandhibandha and Rasabandha, the two most characteristic genres of Apabhramsa literature. Several obscure points too in Hemacandra's work are clarified and some welcome light is shed on the function of several classes of matra-metres. Such points of importance of the Svayambhucchandas can be easily multiplied.

The credit of rescuing so valuable a work from oblivion goes entirely to my learned friend Prof. H. D. Velankar, whose researches in the field of classical Indian metres are too important and well-known to need any mention here. His earlier edition of the Svayambhucchandas was based on a single and then only known manuscript from Baroda, which was moreover fragmentary. The printing of the same text revised for the Rajasthan Puratan Granthamala was nearing completion when fortunately, he received quite unexpectedly a palm leaf fragment of another manuscript of the Svayambhucchandas which, along with numerous Buddhist manuscripts was discovered in a Tibetan monastery by the great savant and my friend Pandit Rahula Sankrityayana, and which to a large extent supplied the missing portion of the Svayambhucchandas. The find-spot of this new Ms. fragment and its Old Bengali script are quite significant for the spread and authority of Svayambhu's work. Though the two fragmentary Mss. between themselves cover a major portion of the original text, there still remain several serious lacunas.

Prof. Velankar has, as is his wont, spared no pains to increase the usefulness of the edition. The critical introduction, translations and informative and comparative notes, besides several indices and appendices readily reveal his acumen, thoroughness and erudition. Moreover, he has also included in the present edition Rajasekhara's Chandahsekhara, an eleventh century Sanskrit version of the Svayambhucchandas, only a fragment of which comprising the fifth chapter is preserved to us. Someday we may hope to discover the missing portions of the prosodic works of Svayambhn and Rajasekhara.

I am very happy to say that we have arranged to bring out further in this series two other equally important works of classical Indian prosody, viz. the Vrttajatisamuccaya of Virahanka and the Kavidarpana, both edited by Prof. Velankar. His co-operation is always readily forthcoming, one happy result of which was his standard and scholarly edition of Hemacandra's Chandonusasana which I was glad to include in the Singhi Jaina Series and publish in 1961.

In conclusion, it is earnestly hoped that for the lovers of Prakrit and Apabhramsa literatures, the publication of the present work will serve to enhance the enjoyment, as Svyambhu declares, 'of the charm and elegance' of the polished and sophisticated muse of Svayambhu and his worthy poetic predecessors and successors.

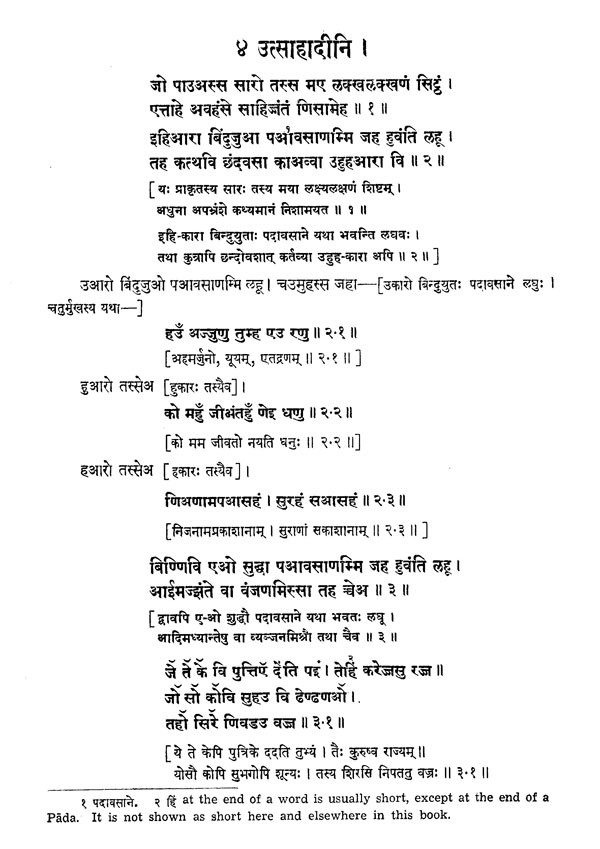

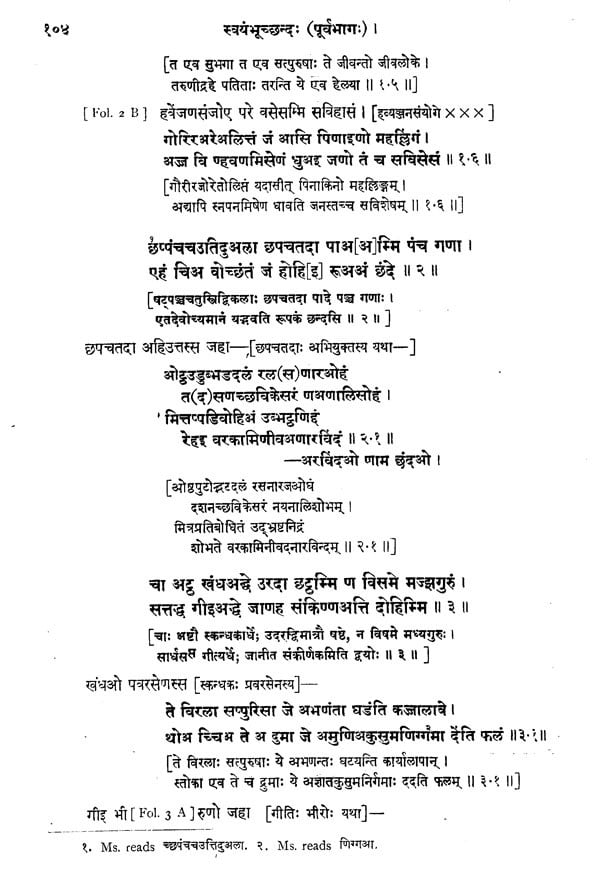

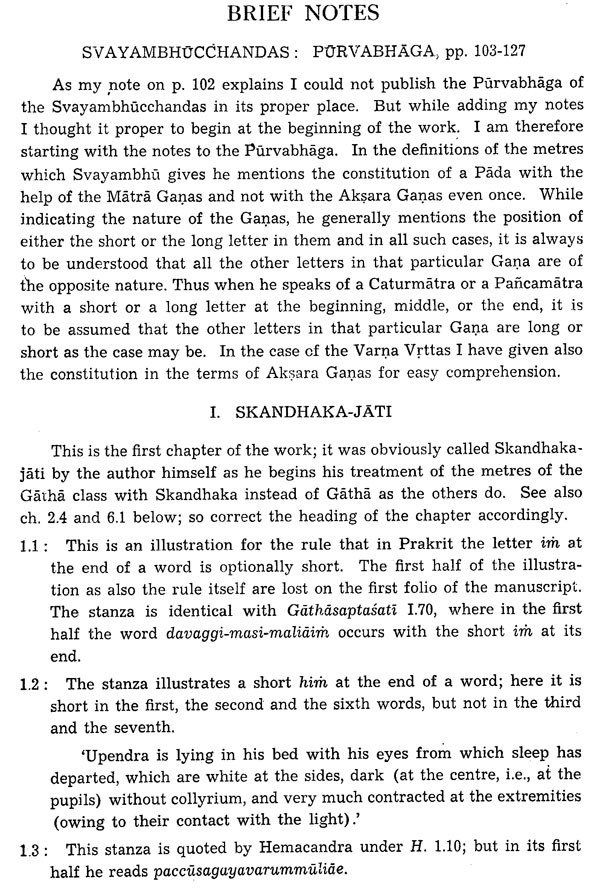

In 1935 I had published the then available portion of the Svayambhuchandas from a paper ms. from the Oriental Institute of Baroda, In the Journal of the Bombay Asiatic Society. I am now re-editing the same along with portions of the earlier part of the work which were supplied by a palm-leaf ms., so kindly given me by Pandit Rahula Sankrtyayana, who secured it from one of the monasteries in Tibet. I got this second ms. at almost the last stage of printing the text and so I had to print it at the end, on pp. 103-127. I have, however, compared this new ms. with the old one and on page 127 I have recorded the variant readings from it in the portions of Sb. chs. 1-4 and 8 which alone are available in it. In giving the Notes, however, I have begun with the earlier portion of the work which was missing in the Baroda ms. Even though this new ms. is only a fragment, it la yet possible to get a proper outline of the nature and extent of the work as a whole with its help. This ms. also contains the concluding part of the work, which is not found in the Baroda ms and I have incorporated it in the printed text as I got it in time for the press.

After the first publication of the Svayambhuchandas, Pandit Nathuram Premi, a reputed Jain scholar, published his work on the History of Jainism and its literature in Hindi, in 1942. This book of his contains learned articles on several Jain authors who wrote in Sanskrit, Prakrit or Apabhramsa languages. Among these there is one on Mahakavi Svayambhu (pp. 370-387). Here Premi has proved that the author of the Svayambhuchandas had also composed two other works both in Apabhramsa, one called Paumacariu on the story of the Jain Ramayana and the other called Ritthanemicariu on that of the Jain Harivamsa. The latter is more generally known as Harivamsa Purana. There is also a third work called Pancamicariu which too is ascribed to Svayambhu by his son Tribhuvana ; but its mss. are not yet available. Of these three works of Svayambhu, one, namely, Poumacariu, is now carefully and critically edited by Dr. H. C. Bhayani, my colleague at the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, and published in the Singhi Jain Granthamala, Bombay, 1953. In the Introduction to this edition Dr. Bhayani has very thoroughly examined the question of the date and authorship of Svayambhe on the basis of all the available material at that time. I am particularly happy to say that his brilliant guess about the contents of the earlier part of the Svayambhuchandas which was missing in the Baroda mss. has proved to be correct by the discovery of the palm leaf mss. of that work mentioned above.

As shown by Premi and Bhayani Svayambhu is respectfully mentioned by Puspadanta in his Mahapurana and so must have lived before the latter half of the 10th century A.D. He probably belonged to the same part of the country in which Puspadanta lived. Bhayani also maintains that Dhanapala, author of the Bhavisayatta-Kaha, has probably been influenced by Svayambhu's Paumacariu. Rajasekhara's Chandahsekhara, of which only the 5th chapter is at present available, also appears in many parts to be a close Sanskrit rendering of the corresponding portions from the Svayambhuchandas. Similarly, many of Hemacandra's illustrations of the Sanskrit metres given in his Chandonusasana appear to be closely modelled on those of Svayambhu, who has given them in Prakrit.

The present edition is mainly based upon the paper ms. in the Oriental Institute, Baroda. This ms. is incomplete towards the beginning and consists of foil. 23-63 only. It is dated Samvat 1927 Asvin Suddha Pancami, Thursday and was copied by one Krishna Deva at Ramnagar. Fol. 33b is blank, but no matter is dropped. The handwriting is clear and in Devanagari characters. It is generally correctly copied out and contains brief explanations in Sanskrit, or more usually only a Sanskrit rendering of a few words written either in the margin or just above the word which is sought to be explained. I have given all these in the footnotes under the text. It would appear that the present ms. is only a copy of another, which was used by a careful student or reader, who had added these brief Sanskrit Tippanis. The copyist is generally careful in reproducing, but his oversight and ignorance are sometimes disclosed and show that he did not always understand the meaning of what he copied. He always writes both ba and va as va, whether as a single letter or in a conjunct and employs the Varganunasika almost always in the case of n and n, sometimes in that of n, but rarely if at all in the case of n and m. A more characteristic feature of his writing, however, is a recurring ex-change of the letters ra and va; sometimes pa is read for e and vice versa. I have corrected these mistakes where they were obvious and have regularly employed an Anusvara for all the Varga-Anunasikas. Omissions of letters are corrected by writing them immediately above the line or in the margin, by our scribe. In the Apabhramsa section, letters which are intended to be pronounced short for metre are sometimes shown by an Ardhacandra mark above them by him and this is true also of the nasalised i or hi in the Prakrit section, though such short letters are hardly used in the definitions and illustrations of the Varna Vrttas.

The second ms. or rather the fragment of it, mentioned above, is written in old Bengali characters on small palm leaves, which appear to have been numbered, but it is difficult to decipher them. Its size is 9,1/2 x 2 inches ; it has 16 folios in all. It is without a beginning, but has the concluding portion of the work which ends on the last but one folio and neither of these is numbered. This obviously last folio contains some other matter, not connected with prosody, only on the obverse side, the reverse side being blank. There are on an average 6 lines in a page and each line contains about 45 letters. Fortunately in the first 12 folios we have portions of the earlier part of the work which is wanting in the Baroda ms. and these are sufficient to give us a rough idea of the complete picture of the Svayambhuchandas as regards its contents. It thus seems to contain 13 chapters in all, of which the first eight are devoted to the Prakrit metres and the last five to the Apabhramsa metres. These chapters which are marked by a recurring stanza occurring at the end, have been generally given different titles signifying their contents. The author, however, nowhere mentions the number of a particular chapter or their total number in his work; this has to be guessed from the recurring stanza that refers to the subject matter discussed in the stanzas preceding it. This recurring stanza briefly describes the work as 'one which has five Amsas (namely, those that contain 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 Matras in them) as its essential feature, which contains ample matter, and which is clear (for comprehension) owing to the definition as well as the illustration being given together in the same stanza or line'.

**Contents and Sample Pages**