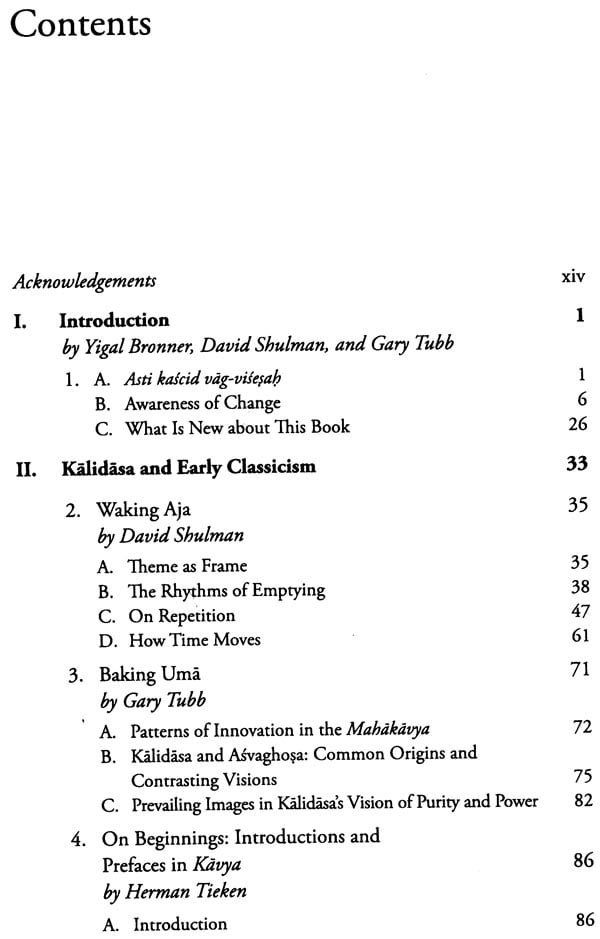

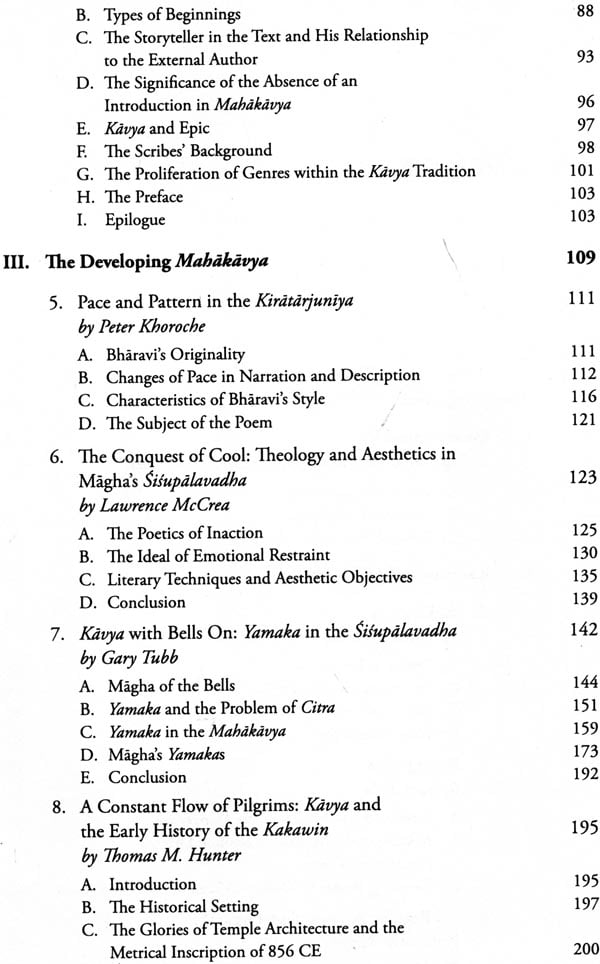

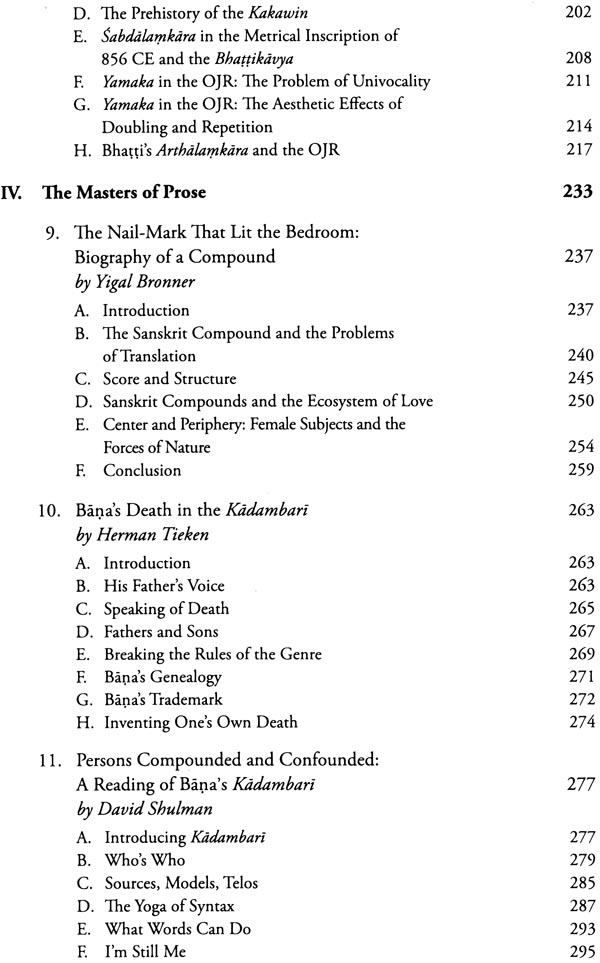

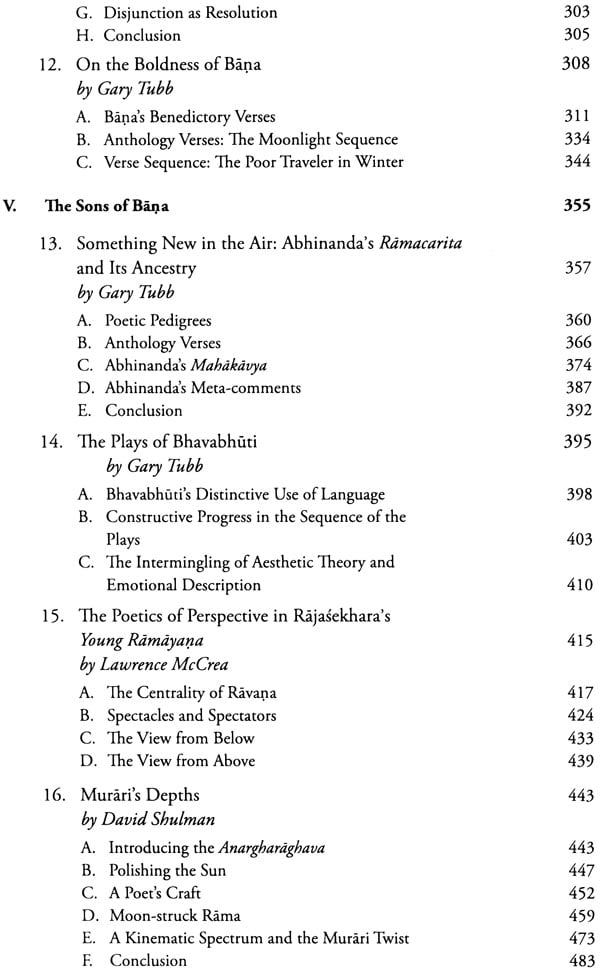

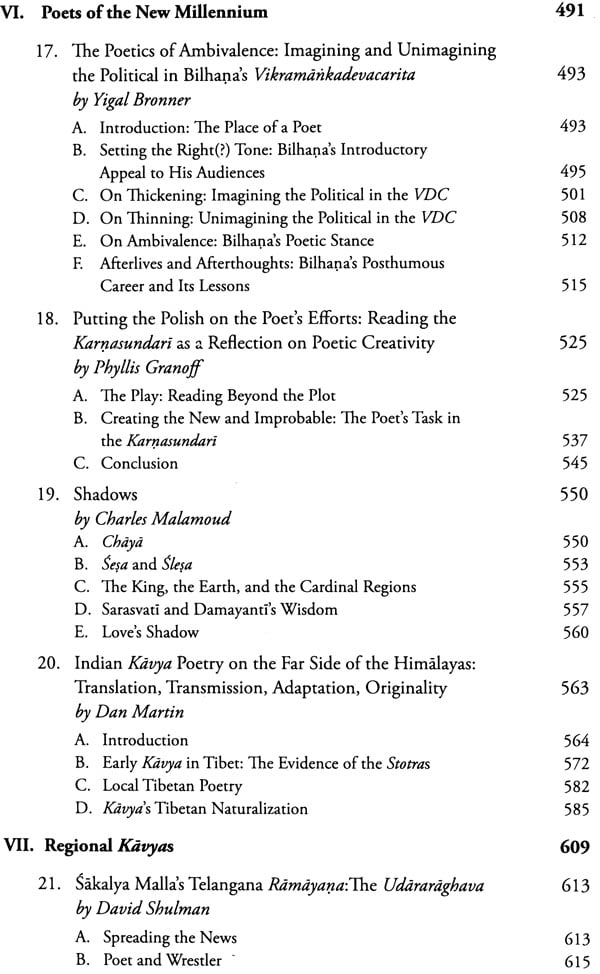

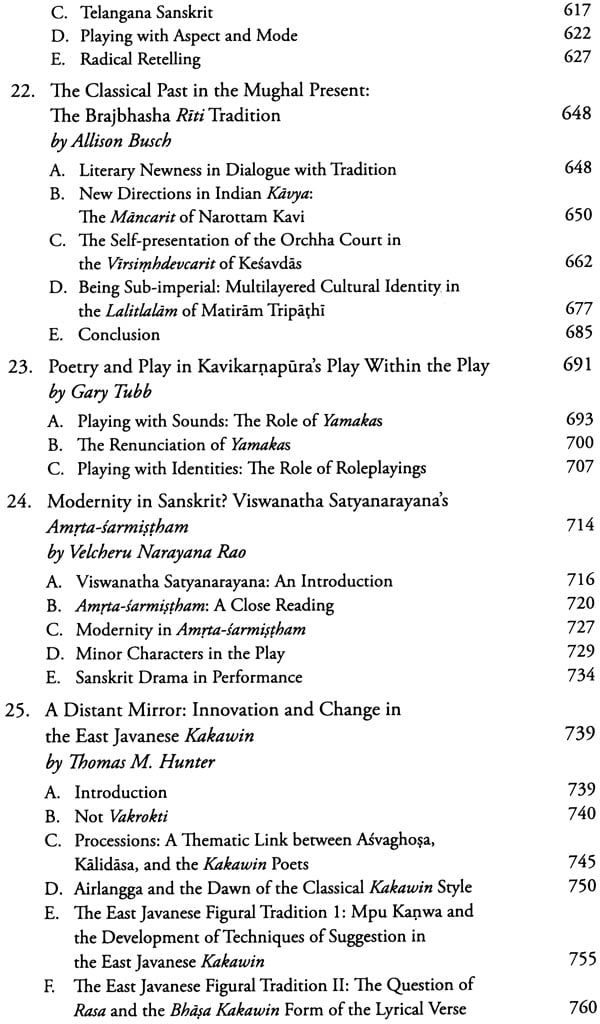

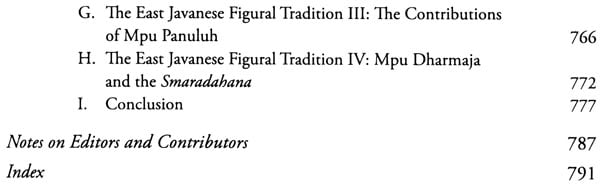

Toward a History of Kavya Literature

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAQ337 |

| Author: | Yigal Bronner & David Shulman |

| Publisher: | Oxford University Press, New Delhi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2014 |

| ISBN: | 9780199453559 |

| Pages: | 820 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 900 gm |

Book Description

With a panoramic overview of South Asian Classical literature, this book identifies critical moments of breakthrough and innovation in Sanskrit literature – moments when the basic rules of composition and the aesthetic and poetic goals underwent dramatic change. It contests the still prevalent notion that Sanskrit Poetry was impervious to change and that it underwent decline after a supposed acme in the period of Kalidasa.

The Essays in this volume focus on extended moments of Brilliant innovation within the kavya tradition, including the new poetic models put in place by Bharavi and Magha, the revolutionary period in Kannauj linked to bana his predecessors and his great successors, and the transformative works of poets of genius such as Bilhana sriharsa rajasekhara, and Murari. It also Examines the origins of Kavya and the creative experiments with its forms and practices in early modern Hindi and, beyond the subcontinent, in Java and Tibet.

Yigal Bronner IS A ASSOCIATE Professor in the department of Asian Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He specializes in Sanskrit poetry, poetic theory and South Asian intellectual history. He is the author of Extreme poetry: The south Asian Movement of Simultaneous Narration 2010)

David Shulmanis Renee Lang Professor Humanistic Studies at the hebrew Univesity of Jerusalem. He has published widely on the cultural history of southern India and on Philosogical topics in Sanskrit, Tamil, and telugu. His recent publications includes More than real:a History of Imagination in South India (2012)

. There is a tradition that Kalidasa, one of the greatest of the Sanskrit poets, was originally an ignorant yokel. Married, in complicated circumstances, to a highly sophisticated princess, he was so ashamed by his lack of education that he sought the help of the goddess Kall. She filled him with the power of poetic invention. When he returned, thus transformed, to his new bride and spoke to her with his new- found gift, she was amazed and said: asti kascid vag-visesah, literally, "There's something different about your speech.

This is a pregnant statement. For one thing, each of the first three words uttered by the princess is the opening to one of Kalidasa's three major poems: asti is the first word of the Kumarasambhava; kascid of the Meghaduta; and vag of the Raghuvamsa. So the sentence provides a conspectus of the poet's oeuvre, possibly in the order in which these works were composed. Moreover, the tradition has put into the mouth of the princess an implicit evaluation of these three works as distinctive, indeed ground-breaking. Although our record of pre-Kalidasa Sanskrit poetry is sparse, there is good reason to think that each of the three works does something profoundly new. On the level of genre alone, each innovates radically-and much more could be said about syntax, thematics, metrics, and other parameters of style.

Here the tradition echoes Kalidasa's own statement in the prologue to his play Malavikagnimitra. The Director (sutradhdra) is conversing with his assistant, who asks:

Why should we prefer a play by Kalidasa, a contemporary poet, to the works of such famous authors as Bhasa, Saumilla, and Kaviputrai/ The Director responds:

You're speaking without thinking, my friend. Look:

Not everything that is old is therefore good.

Nor should a poem be faulted just because it's new.

Able critics look closely before approving either one.

Only fools blindly follow what others think.

The assistant seems to imply that "older is better" -a view that lingers on in most so-called histories of Sanskrit poetry. The dominant, classicizing view holds that Sanskrit poetry reached its peak very early, and that everything that happened later-after the fifth century CE-belonged to a process of long decay. This view paradoxically goes hand in hand with a perception that commentators within the Sanskrit tradition have emphasized, namely the timelessness of the Sanskrit language, in general, and of its individual literary productions. It is as if innovation, in a positive sense, were totally alien to this long, continuously creative tradition.

In response to the assistant's rhetorical query, the Director reminds us that literary merit is not necessarily a function of age but can only be determined by open-minded, close critical inspection. There is room, according to Kalidasa's verse, for something new to emerge--and clearly he thinks his new play is at least as worthy as his predecessors' works. It is thus somewhat ironic that a later perspective has enshrined Kalidasa as the first and last great Sanskrit poet, a changeless and timeless standard of excellence in a tradition that has steadily declined. One result of this stultifying presumption is that most of Sanskrit poetry has not been carefully read, at least not in the last two centuries.

If, however, we adopt the Director's advice and read Sanskrit kavya with an open mind, we see evidence of tremendous vitality and continuous change.

What is more, the notion of innovation is a remarkably consistent topos throughout the classical and medieval literature. The poets themselves very often remark on the novelty of their own work as well as that of particular poets who came before them. In this sense, Kalidasas verse-which names three of his predecessors-is a relatively early example of a recurrent theme. Here is a small sample.

Some two centuries after Kalidasa, Bana-one of the most original figures in the tradition by any standard-offers the following paronomastic assertion of his own creativity:

Pedestrian poets are as common as domestic dogs.

You can hear them barking in house after house.

Inventive poets, truly outstanding,

are as rare as superpolypedal beasts.

The point of the verse is not so much a devaluation of contemporaneous poets-although that, too, is a common theme-but rather an assertion that innovation is the major criterion for poetic merit. This principle is strongly and overtly stated by Magha (seventh century) in a famous verse describing Krsna's first glimpse of Mount Raivataka (Girnar):

Even though Murari [Krsna] saw the mountain not for the first time,

he was amazed as if he'd never seen it before.

The essence of beauty is to become new

at every moment.

Dharmakirti, probably a contemporary of Magha, poignantly describes the experience of a poet who is breaking new ground:

No one is walking ahead.

No one follows behind.

There are no fresh footprints on the road.

Could I be all alone?

I understand.

The path taken by those before me

is now desolate,

**Contents and Sample Pages**