The Tradition of Mask in Indian Culture - An Anthropological Study of Majuli, Assam

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAP361 |

| Author: | Arifur Zaman |

| Publisher: | ARYAN BOOKS INTERNATIONAL |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9788173055201 |

| Pages: | 489 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.5 inch X 6.5 inch |

| Weight | 590 gm |

Book Description

Masks are artificial faces worn for disguise, generally to assume and to frighten. They are often worn to conceal feelings and also as coverings to hide or protect the faces. They may be carved, moulded, or even woven objects, which are worn over the face or on the head. The chief motivation for making mask was probably to satisfy the magico-religious needs of the primitive people.

From time immemorial Assam has a thought provoking heritage of making and using masks. The masks, especially the bamboo split made masks, are integral to the Vaishnavism of Assam. The great saint Srimanta Sankaradeva (1449-1568) propagated Neo-Vaishnavism in North East India, which was a part of the larger pan-Indian resurgence of unflinching devotion The Natun (new) Chamaguri Satra is a renowned Vaishnavite monastery of Majuli, which has a long and rich tradition of mask making. It is pertinent to note that Majuli is the nerve-centre of Assam's Vaishnavism, where the eye- catching tradition of mask making is nourished in the four satras (Vaishnavite monasteries). The present volume has meticulously churned the heritage of the Natun Chamaguri Satra, and has shown the economic, social, cultural and religious significance of the masks as also a praiseworthy record of the available masks of the area.

Mask is an integral object of culture complex in many societies in a cross-cultural perspective. It is one of the forms of camouflages which conceal one's factual and natural identity and reveal the identity of another being. Masks have a great influence on human society and among some, it is conspicuously related with religious, socio-economic, as well as cultural aspects. The study under consideration was carried out in one of the important Vaishnavite satras (monastery or math) of Majuli, situated at Jorhat district of Assam. The concerned satra has a praiseworthy tradition of mask making whose aesthetic insinuation as well as confessions of the maker have attracted visitors from many parts of the world. They also stand as one of the proud components of cultural heritage of Assam as well as for the whole of the country. They are considered as august and egotistical archetype of their master's creation. The mask makers are endowed with dignified appellation like Sangeet Nataka Academy Award conferred by the Government of India, awarded artist pension by the state government, etc., for their praiseworthy skills. The Natun Chamaguri Satra is also known as Majuli Chamaguri Satra. The villagers, where the satra is located, are engaged in many economic activities like agriculture, government services, teaching, petty trade, etc., in order to maintain their day to day life. Basic data for the present study was mainly collected from the study of this satra and cross-verification was made with other mask making satras of Majuli; these include Alengi Narasimha Satra, Bihimpur Satra and Prachin Chamaguri Satra.

At the very outset I would like to express my indebtedness to my guide as well as philosopher, who is independently and also collectively instrumental for what I am today. My heartiest thanks and gratitude goes to Dr. Birinchi K. Medhi, Professor of Anthropology, Gauhati University, for guiding and helping me to undertake the study. His erudition and scholarship has been a great source of inspiration to me. I would remain beholden to him because without his learned guidance, the study would not have seen the light of the day. This study, perhaps, could not have been completed without the constant inspirations that I received from Dr. Zoii Nath Sarmah, Executive President and Director, North Eastern Regional Institute of Management, Guwahati. He not only encouraged me and strengthened my resolve to carryon with the study, but also showered me with all possible help and facilities. I am extremely grateful to him. My heartfelt thanks also goes to Mr. Abani Borthakur, Census Compiler, Directorate of Census Operation, Assam, for providing me with every possible help regarding the latest census data.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank the lovable people of the Natun Chamaguri Village, Majuli, young and old, for their full cooperation and help, without whom my field-work would not have been possible. I am grateful to Sri Sri Koshakanta Deva Goswami, the Satradhikar of the Natun Chamaguri Satra, and his family members, for their untiring help and inspiration. I am also thankful to Sri Hem Chandra Goswami, a mask maker of repute, Sri Krishna Goswami, Artist and Lecturer, Government Art College, Guwahati, without whose help it would not have been possible for me to complete this venture. I am also indebted to Sri Sri Janardan Deva Goswami, Satradhikar, Uttar Kamalabari Satra, Majuli, and Mr. Hiteshwar Bora, a social activist of Majuli, who were of great help and inspiration to me during my stay at Majuli through their hospitality as well as scholaristic attitudes. A large number of individuals as well as bhaktas (devotees) and other personnels of different satras of Majuli, employees of different offices and establishments helped and assisted me in completing the study. Despite their normal preoccupations and official duties, they always found the time to cooperate with me whole-heartedly during the course of this study. I owe my deep sense of gratitude to them. I offer my sincere apology for not being able to name each one of them here.

I offer my heartfelt thanks to Ms. Asha Gupta of Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, New Delhi, for guiding me during my library work there. I am thankful to the staff of the libraries of Gauhati University, National Institute of Rural Development, Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development, District Library, Guwahati, Library of North Eastern Regional Institute of Management, Cotton College Library, Arya Vidyapeeth College Library, National Institute of People's Co-operation and Child Development, Assam, Institute of Research for Tribals and Scheduled Castes, and others for enabling me to do a literature survey and to collect the required data. I am indebted to the museum personnel of Sri manta Sankaradeva Kalakshetra, Assam State Museum, Madhab Chandra Goswami Museum of Anthropology Department, Gauhati University, National Museum of Delhi, Salar Jang Museum of Hyderabad, Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya, Bhopal, etc., which I visited for gathering data regarding masks as well as art forms of different cultures of the world.

I feel immense pleasure in expressing my gratitude to Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya, Bhopal. This esteemed organisation is the main catalyst to transform my study into an eye-catching book. I must put an record my deep sense of gratitude towards Prof. KK Misra, the then director of IGRMS, and all the concerned persons of the organisation.

I owe a lot to my family members and my sincere thanks are reserved for my father, Sri Mohammad Ali, whose help and immense patience in all directions saw me through. I extend my sincere thanks to all those individuals and establishments whose names cannot be included here for dearth of space but who have helped me in one way or the other during the course of the study.

1.1 PRELUDE

Masks are artificial faces worn for disguise, generally to assume and to frighten. They are often worn to conceal feelings and also as coverings to hide or protect the faces. They may be carved, moulded, or even woven objects, which are worn over the face or on the head. Sometimes, a mask may be as large as a also be life-sized object. According to The New International Webster's Student Dictionary of the English Language (Landau, 2000: 442), the word mask means 'I. A cover or disguise for the features; 2. A protective appliance for the face or head; 3. Anything used to disguise or dissimilate; 4. A likeness of a face cast in plaster, clay, etc.; 5. An elaborate dramatic presentation with music, fanciful costumes, etc., and actors masked as allegorical or mythological subjects; also the text or music for it; 6. Masquerade; 7. An artificial covering for the face, used esp. by Greek and Roman actors'. The description of mask in the New Encyclopedia Britannica (1991: 910) aptly brings out the sense in which it has been used in this study. According to this encyclopedia, 'Mask, type of disguise, commonly an object worn over or in front of the face to hide the identity of the wearer. The features of the mask not only conceal those of the wearer, but also project the image of another personality or being. This dual function is a basic characteristic of mask'. Masks are found to have been used in different parts of the world right from earliest ages in the history of mankind. Pani (1986: 1) writes, Nobody knows where and when mask originated. It seems probable that deep in the prehistoric past each primitive society developed its own masks to minimize the feeling of vulnerability. At the time scientific reason did not develop to explain the various phenomena of nature to which the primitive man was helplessly exposed. He, therefore, felt highly insecure and vulnerable. He could see that the forces of nature, which control him are basically of two kinds: the benevolent, and the malevolent. The former, he thought, are the acts of the gods whereas the latter, that of the demons and evil spirits. Thus he started creating myths and desperately tried to materialize these supernatural powers so that, through appropriate rituals which are but enactments of myths, the gods could be pleased and the evil spirits appeased. As a result, from his mythmaking faculty were born many idols, images and icons. And mask was born as a special kind of icon.

The chief motivation for making mask is probably to satisfy the magico-religious need of the primitive people. In their day to day life, they had to face a good number of hindrances like scarcity of food material, disease and death, natural calamities, etc., which they intended to overcome by wearing masks. The oldest evidence of the use of mask were encountered in the walls of cave and rock shelters during the Upper Palaeoli this period. Most of those were the paintings of hunters who were seen to cover their faces with animal masks. Even after achieving the higher culture and economy, the tradition of mask persisted in the human society. Even today it is not possible for men to fully control the nature; uncertainty still looms large on the life of human beings. To overcome such situations men wear masks, and through this they try to achieve happiness and prosperity by warding off the uncertainty of life. Although mask assumes various forms, the principal aim of the people is to get strength and prosperity by wearing masks. It is believed that by wearing animal mask, one can acquire the strength of that animal. Although both malevolent and benevolent mask are common in different societies, the principal function of masks is to ensure the cultural existence of men.

Laude (1971: 142) observes,

The masks protects. Indeed, should the vital force liberated at the time of death be allowed to wander, it would harass the living and would disturb composure. Trapped in the mask, it is controlled, one might say exploited, and then redistributed for the benefit of the collectivity. But the mask also safeguards the dancer who during the ceremony, must be protected from the influence of the instrument he manipulated. In fact, humanity has travelled a long way and has undergone transformation, and man has become civilized and more objective in his outlook; but some elements of primitive psychology still exist him in the form of seen and unseen fear for the unknown even in the highly developed society. This is best expressed by the use of masks in different cultures. Though masks are as varied as the makers' imagination, beliefs and needs, they reflect the artistic and religious devotion of those who made them since the earliest time. The forms of masks have changed as the centre of which they had been a part, but their intrinsic value have remained the same, and thus time gets captured in the mask.

We look at the mask as a means of escaping from the reality of daily life to have an experience of participating in multifarious life in the universe. The wearer of a mask can sail out in the world of ecstasy; he can turn into a spirit, an animal, a demon, or a god that the mask depicts. As a social being, man lives in a community of similar individuals with whom he comes in contact constantly in the way of direct or indirect competition. He is equal to all in the sphere of socio-economic life, but his sub-conscious mind wants him to be distinguished and he is transformed into a character, to instill the fear among others. He does so to earn reverence and respect from others, at least for some time, on certain occasions. This he achieves through masks, because when a man wears a mask, he is transformed into the character of the mask.

| Unveiling the Mask | v | |

| Preface | Xl | |

| List of Figures | xv | |

| List of Plates | XVll | |

| 1 | Introduction | 1 |

| 1.1 | Prelude | 1 |

| 1.2 | The Assamese | 8 |

| 1.3 | Majuli | 14 |

| 1.4 | Aspects of Satra | 21 |

| 1.5 | The Village Scenario | 23 |

| 2 | Masks in the Context of Culture | 27 |

| 3 | Prologue to Mask | 47 |

| 3.1 | Underlying Meaning of Mask | 47 |

| 3.2 | Uses of Mask | 57 |

| 4 | Heritage of Mask at Majuli | 68 |

| 4.1 | Mask Making Tradition | 68 |

| 4.2 | Making of Mask | 70 |

| 4.3 | Type of Masks | 74 |

| 4.4 | Mask and Gender | 78 |

| 4.5 | Some Aspects Integral to Masks | 81 |

| 5 | Available Masks of Natun Chamaguri Satra | 84 |

| 6 | Conclusion | 122 |

| Bibliography | 131 | |

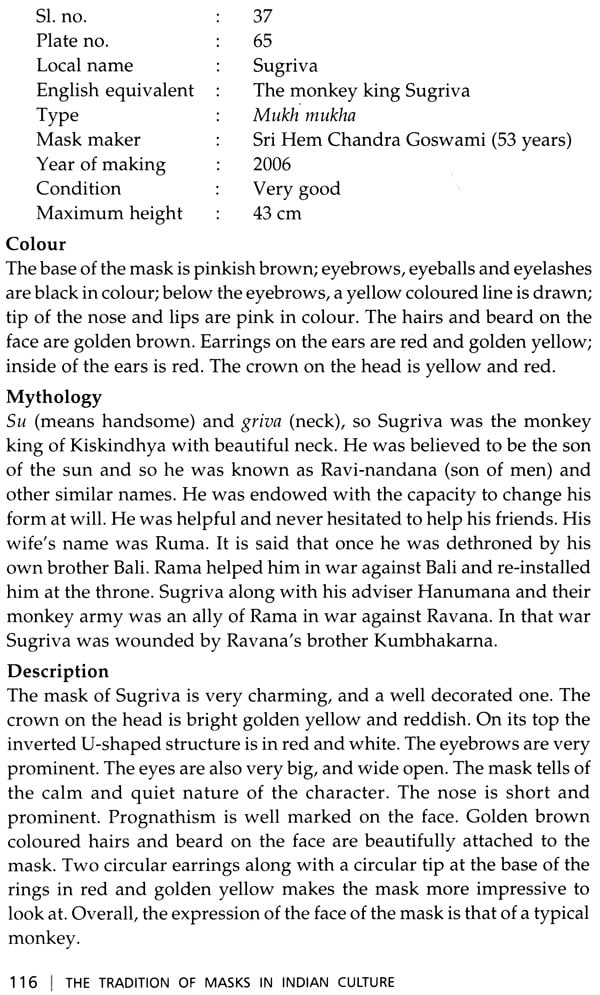

| Index | 143 |