Understanding Harappa (Civilization in the Greater Indus Valley)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAS232 |

| Author: | Shereen Ratnagar |

| Publisher: | Tulika Books |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2019 |

| ISBN: | 9789382381662 |

| Pages: | 176 (Throughout Color and B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 280 gm |

Book Description

This slim volume is an attempt to rouse the interest of students and non-specialists in the early civilization of the Indus valley and adjoining regions of Pakistan and India. The challenges of archaeological interpretation are discussed, together with maps, site plans and an illustration of artefacts, but the evidence is presented in social terms rather than in a technical way. In an attempt to cast an overall perspective, the Indus civilization is presented in the context of contemporary cultural development in South Asia as well as Western and Central Asia.

The third edition of this volume included references to new ideas on the Indus civilization and to excavations at a small but significant site. The revised and updated fourth edition, of which this is a reprint, contains additional material on Dholavira and the harnessing of flash-floods.

Shereen Ratnagar took her training in the archaeology of India at the Deccan College, Pune, and in Mesopotamian archaeology at the University of London Institute of Archaeology. She taught for many years at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. Her publications include Encounters: The Westerly Trade of the Harappa Civilization, Enquiries into the Political Organization of Harappan Society, The End of the Great Harappan Tradition, Mobile and Marginalized Peoples, The Other Indians: Essays on Pastoralists and Prehistoric Tribal People, Trading Encounters: From the Euphrates to the Indus in the Bronze Age, Ayodhya: Archaeology after Excavation, The Time chart History of Ancient Egypt, Makers and Shapers: Early Indian Technology in the Household, Village and Urban Workshop, and Being Tribal.

In this book I have tried to present the salient aspects of the Harappan civilization in a way that will arouse the interest of the student and the lay reader. It is not my aim to give exhaustive information or to discuss the technicalities of chronology but to give an outline of the archaeological evidence in a social and economic framework. The Harappan civilization belongs to the 'Bronze Age', which is unique as the stage in which the first stratified societies-states and cities-appeared in some parts of the world. These state-societies had characteristics that distinguish them from states that were to develop later.

In an endeavour for clarity, I have made occasional references to the ways in which archaeology creates knowledge, and a certain degree of repetition has become inevitable.

Rakesh Batabyal, Fellow at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study (Shimla), took on the role of 'lay reader' of the draft and made many useful and insightful suggestions. Salima Tyabji and later Usha Hemmadi gave editorial advice. Nanda Singh, Mumbai, and Arun, Delhi, made the drawings. Affectionate thanks go to Roshan Wadia, who teaches me about architecture.

R.N. Hegde of Ravish Publishers, Pune, suggested the idea of this book: he is one of my strictest critics and his advice has been invaluable.

I take this opportunity to thank the many friends I made in Pakistan, including Dr Niaz Rasool, Director-General of the Archaeological Survey, Dr Mubarak Ali, Byram and Feerooza Avari, Ershad Ali Rid, and Richard Meadow, for their hospitality, friendship, assistance in practical matters, and information on matters cultural and archaeological.

I thank Dr Kalpana Desai, Director, and Ms Toraskar and Dr A. Fondaker, of the Prince of Wales Museum of Western India (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya) for their patience and efficiency which made it easy for me to photograph antiquities in the Museum's galleries. The photographs, which were taken by Anand Udeshi, were financed by a generous grant from the Jerbai Cowasji Dinshaw Adenwalla Trust.

I express my deep gratitude to the Trustees of the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, Mumbai, for believing that a book such as this needed to be published.

I also thank the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, MS University of Baroda, for kindly making available photographs of the important site of Bagasra.

This fourth edition contains some additional material on Dholavira and the harnessing of flash-floods which I hope the reader will enjoy.

The remains of the Indus or Harappan civilization of Pakistan and India, dating from about 2600 Bc to about 2000-1800 Bc, include cities and villages, craft centres, river stations, camp sites, fortified places, and a few probable ports, spread over an immense geographic area, so that the Harappan is said to be the most extensive of the world's earliest civilizations. The sites are found in Sind, Makran, Baluchistan, Punjab, Haryana, north Rajasthan, Kathiawad, Kutch and Badakhshan, in the modern states of Pakistan, India and Afghanistan.

In the literature of archaeology the remains of these sites are often categorized as 'Mature Harappan'. This term refers to the period when the urban centres, crafts and trade of the civilization flourished. It is distinct from both the formative period (termed 'Early Indus' or 'Early Harappan') and the period after the abandonment of the cities and the termination of writing and the crafts (misleadingly termed 'Late Harappan').

The early development of agriculture and animal-rearing and the onset of village life in Pakistan around and after 6500 BC present the first cultural developments that set the stage for the emergence of civilization. During the early period the subsistence economy took its form, some handicraft traditions emerged and, most important, interactions began across various zones of the Indus valley and its surrounding hills and plateaus. The villages of the centuries before 2600 Bc were located not only on the Indus plains as far north as Taxila but also in the river valleys amongst the mountains of Baluchistan. (The sequence of these developments is considered in Chapter 9 of this book.)

The Mature Harappan period in its turn was marked by extensive construction in skilled brick masonry of houses, by walls that encircled several settlements, wells, storage structures and other buildings, and also by bipartite urban settlements with high places and lower but more extensive residential areas. There was a characteristic thick and sturdy red pottery. Specific forms of bronze tools such as curved 'razors', chisels in various sizes and shapes, and flat axes occur across the sites; at the same time there is a relative paucity of distinctive tool types in ground stone and flaked stone.

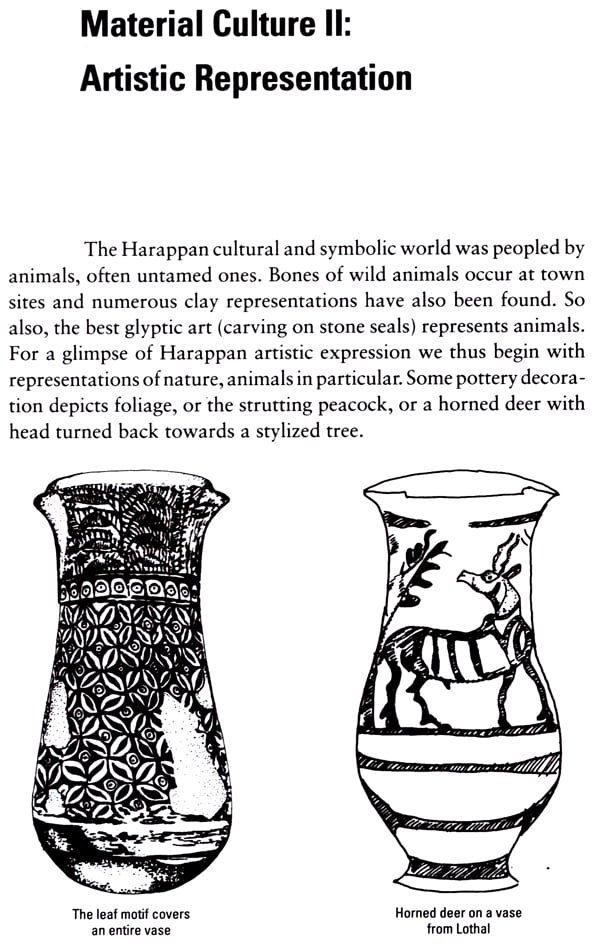

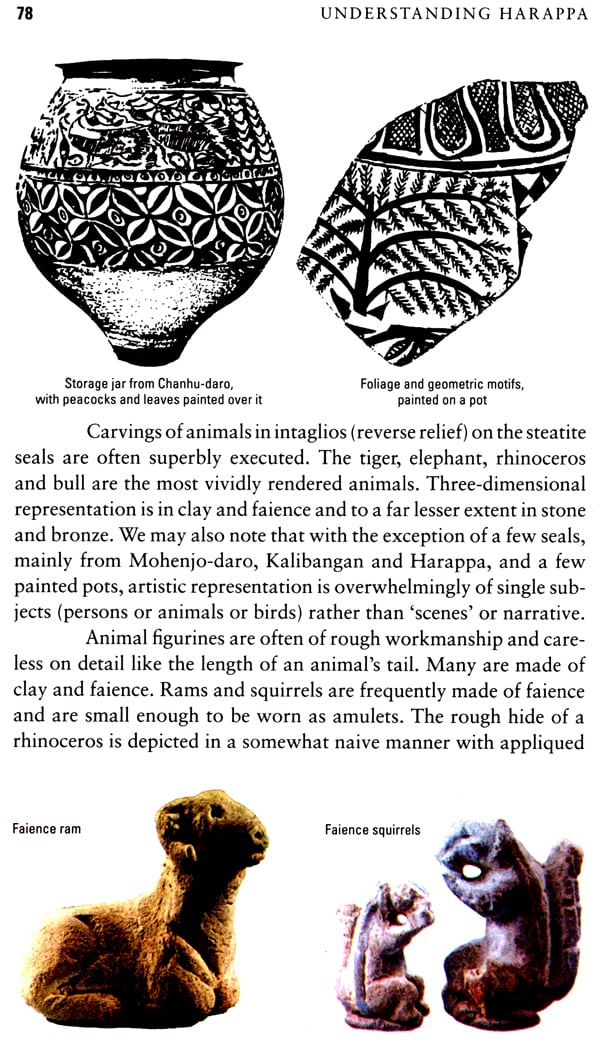

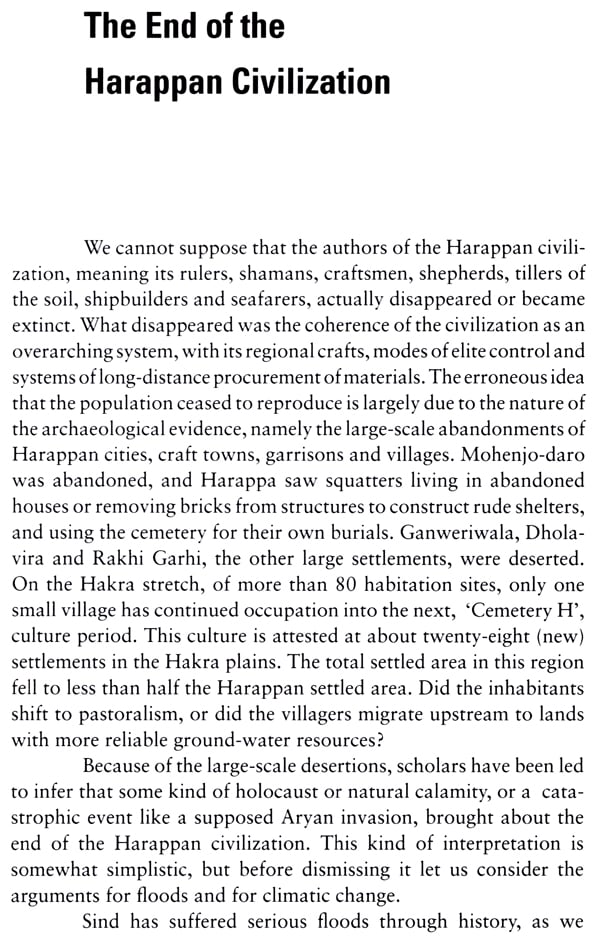

An imaginative terracotta art depicting all kinds of animals as well as people offers much scope for sensitive interpretation. Seals give evidence of another level of artistic creativity. These are shaped for easy handling (for stamping) and have rectangular faces carved with pictorial symbols and writing. Other characteristic elements are beautifully cut and polished cubical stone weights that were only one part of a uniform weighing system; marine shell and ivory with multiple uses including as ornaments and domestic artefacts; baked clay missiles and flat 'cakes' for paving floors and for heat retention at fireplaces; and ornaments made of faience, bronze, silver, gold and semi-precious stones of attractive colours. Culturally significant is a system of writing that was perhaps logographic.

Amongst the features that make the Harappan civilization unique in the third-millennium world are its baked-brick urban buildings and architectural skills, the weight system that appears to have been standardized from the beginning, and the long distances overseas that Harappan materials reached. Other than exceptionally large urban houses there was also water harnessing on an unparalleled scale with probably hundreds of wells sunk, say, twenty metres deep, in the city of Mohenjo-daro. Artificial lakes or tanks were constructed at Dholavira on an island in the Rann of Kutch. The abundant water supply to habitations-we may recall the frequency with which paved bathing floors occur in Harappan houses-would have served not only personal and domestic needs but also, probably, ritual performance. For, the only building identified with some degree of certitude as a religious unit is the Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro, its floor so well paved that we cannot doubt that it held water. Planned water supply to the residential area entailed, in its turn, a system of carrying away used or waste water from the houses: the street drainage system of Mohenjo-daro is rare in the ancient world.

**Contents and Sample Pages**