Women and Gender in Ancient India (A Study of Texts and Inscriptions)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAO650 |

| Author: | Vijaya Lakshmi Singh |

| Publisher: | Aryan Books International |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9788173055171 |

| Pages: | 194 (15 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 10.0 inch X 7.0 inch |

| Weight | 560 gm |

Book Description

Subordination of women is a common feature of almost all stages of history and is prevalent everywhere in the world. However, the extent and form of that subordination has been conditioned by the social and cultural environment in which women have been placed. To understand the position of women in early northern India, this study has been charted in a fashion that includes historiographical trends and perspectives, explores women's spaces through the Buddhist literature, viz. the Therigatha and the Jataka; Sanskrit literature like the Ramayana and Devi Mahatmya (Markandeya Purana), Kalhana's Rajatarangini and also epigraphic materials. Given the diverse and culturally pluralistic environment of India, different interpretations are applied to the images of women.

Looking at women through multiple lenses, multiple voices and sources brought to bear on a particular argument, drawing out alternative position, sometimes subtle, at other times unpopular, is more than just an academic exercise, it has political implications as well. This study is relevant and consequential for contemporary Indian women who are exploring gender justice, which is a significant concern of the day.

Vijaya Laxmi Singh graduated in History Honours from the prestigious Patna Women's College (Avila Convent), Patna. She obtained her M.A. and M.Phil. Degrees from University of Delhi and Ph.D. from Jawaharlal University, Delhi. She is currently Associate Professor in the Department of History and Dy. Director and In-charge of Centre for Professional Development in Higher Education (UGC-ASC), University of Delhi. Her four monographs are: Ujjayini: A Numismatic and Epigraphic Study (1996), Mathura: The Settlement Pattern and Cultural Profile of an Early Historical City (2005), The Saga of First Urbanism in India: Harappan Civilization (2006) and Portraying Cultures in Indian Subcontinent from Ancient to Modern (2011). She has received CICOPS scholarship in 2007 and has been conferred the status of CICOPS Fellow in 2012 by Pavia University, Italy. She has published many papers in national and international academic journals. She has participated and lectured in national and international seminars/colloquiums. She has also been a member of statutory bodies like the Academic Council (1994-98) and Executive Council (2000-2004) of the University of Delhi.

This book is based upon the textual and epigraphic materials of early India. The book is based on selected sources. Sources show deviation from both the conjecture made in the post-Altekerian tradition that originated in colonial period but has ample influence on the writings of post-colonial times as well as projection of women in epigraphic records. The results may not be conventional because even though subordination of women is a common feature of almost all stages of history and is prevalent everywhere in the world, the extent and form of that subordination has been conditioned by the social and cultural environment in which women have been placed. Even today, women are often forced to choose between the demanding career clock and ever-ticking biological clock.

To understand the position of women in early India, we have to study women in their wider context. The first chapter is the introductory chapter which deals with two aspects: one entitled 'Historiographical Trends and Perspectives in Indian and Non-Indian Sources for Early Historical Societies' and the second entitled 'Ancient India and the Women Question: Brief Survey from the Earliest Period to Pre-Maurya Period'.

There is a spate of studies on the gender question, some on Buddhist literature. In the second chapter we have tried to explore the women's space in Buddhist society. There is a general belief that history of women in Buddhism is a linear narrative of progress from oppression to liberation. But this is not true as patriarchal value system, often bordering on misogyny, has been quite pronounced in Buddhism. Within this ambit we have to define the place of women and construction of gender in androcentric tradition. Buddhism is paradoxically neither sexist nor as egalitarian as is commonly thought. We notice two kinds of approaches in Buddhist texts; the Buddhist bias against women and attempts to overcome this bias (the canonical texts) and second the active role of Buddhist women to counter the stereotype of women as passive cultural subjects (Therigatha).

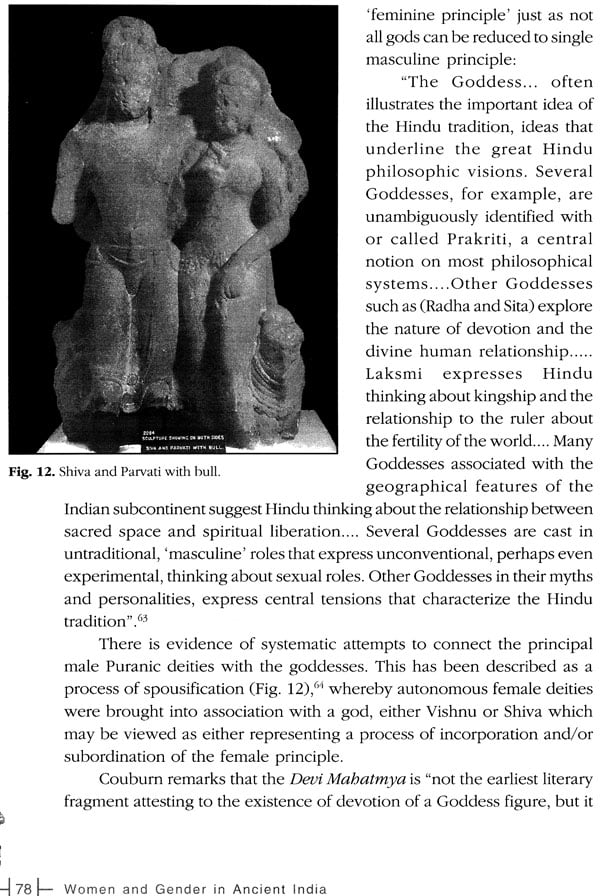

In the third chapter (i) ' Gender Differentiation and Contentious Feminine Voice of Sita in the Ramayana' reflects the condition of India during 4th cent. Bc-4th cent. AD. The sex appropriate ideals prominent throughout the Ramayana are reflections of the patriarchal values that structured ancient Indian society. We consider the Ramayana as post-Mauryan. The centre of attention in Valmiki's composition is literature, whether mythical or real story, it is a reflection of the thoughts prevailing during the Kushana-Gupta period. (ii) Devi Mahatmya (Markandeya Purana) and mythical and theological traditions of goddess worship in early India is based on the original text Devi Mahatmya translated by V.S. Agrawala and its scholarly analysis by Coburn. The purpose of this study is not to deal with religious texts per se, but to consider literary characters presented to us as human, taking part in ordinary human pursuits, albeit in a somewhat extraordinary manner at times, and to discover in them greater or less degree of divine identity or at least evidence of their being special foci of their divine predilection. We find in the lives of these epic women characters, a frequent, sometimes constant intervention of the divine, often at the cost of pain and shame, at other times bringing comfort, reassurance and ultimate glory.

The connections suggested between goddesses and women in Indian society have been questioned. The distinction is made between feminization of certain attributes—righteousness, justice, wealth, earning—or more accurately their embodiment in the female form, and the elevation of strong and aberrant women with these attributes to divinity. The goddess is a product of the first process, not the second. The implication of this distinction lies in this: that the symbolic valuation of the form is not a reflection of the actual material and the historical condition in which they take shape. A necessary co-relation between powerful goddesses and empowered women would imply simplistic theories of role models and uni-gender projection.

The fourth chapter `Gendered Identity: The Case of Queen Didda of Historical Kashmir' deals with Kalhana's text Rajatarangini where he highlights the power and agency of women in royal court culture in two essential ways—as sovereign rulers in their own right and as powers behind the throne. Power is wrested and executed by them in what is essentially a patriarchal edifice, thus causing a certain amount of tension and ambiguity, not only in specific phases of Kashmir's history but also in Kalhana's portrayal of them. On the other hand, the text makes it very clear that the queen had a very definite political role to play—whether as a part of policy-dictated matrimonial alliances or as a popular choice of wielding power. In this sense, the notion that 'the kingship or the state was associated with the control of women and was an instrument of their subjugation' does not hold true for women in Rajatarangini. The question which arises here is that 'Is the force of matrilineal ideology and norms overrated?' Have we imputed greater hegemony to matrilineal orthodoxy than is warranted?' Continuous research and close scrutiny of source material is needed to bring real people in the past alive and to arrive at a fresh understanding of the history of women in early Kashmir.

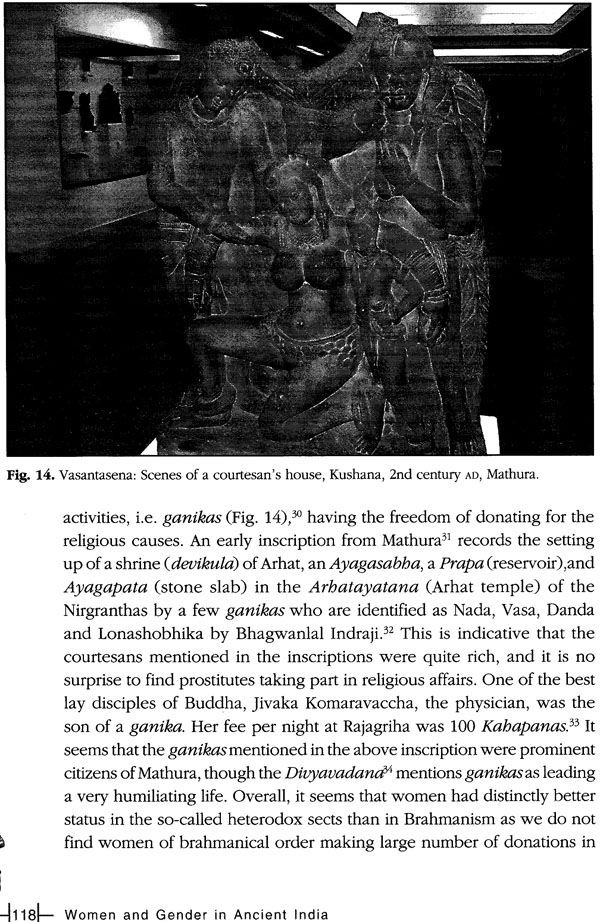

The fifth chapter 'Gender in Inscriptions' discusses women in various inscriptions. The period from the third century BC to the early centuries of Christian era was very important from the point of gendered history of Buddhist/Jaina sites in north India, the testimony of which is seen in the epigraphic data. Hundreds of inscriptions are found at the sites of Mathura, Sanchi, Bharhut.

One of the significant aspects of the societies of Mathura, Sanchi and Bharhut is represented by religious donations of female donors. These donors are also of two categories: (i) queens and women of royal family, (ii) ordinary women. Donations from queens and women of royal family are of course known from the early phases of a few Buddhist sites.

The role of women in the political history of ancient India is confined to royal families and the participation of common women like common men in the state administration has never been dealt with in contemporary history. Thus, the role of common women cannot be ascertained for want of literary or other data though women in the Saka-Kushana period are noticed making small donations for religious causes (Buddhist, Jaina and Brahmanical) as discussed above. Moreover, the Brahmanical social structure little encouraged public life for women. Owing to the lack of sources and the little impact of the common man on the political history in monarchical times, we may conclude that the role of common women cannot be systematically analyzed for want of data. But we have ample proof of royal women playing vital role in the state affairs as instruments of political alliance, Queen mothers influencing decisions and acquiring crowns for their sons, Regent Queens (in the event of the death of their king husbands, when their sons were minors), Queen consorts influencing the king at the helm of political affairs and in Kashmir, Queen ruling the state. The approach in traditional historiography is textual and it almost totally excludes epigraphically records. To make real women visible on historical stage, the epigraphic records need to be collected and classified.

Contents

| Prologue | v | |

| Acknowledgements | xi | |

| List of Abbreviations | xiii | |

| List of Illustrations | xv | |

| I. | Women and Gender in History | 1 |

| A. | Historiographical Trends and Perspectives in Indian and Non-Indian for Early Historical Societies | 1 |

| B. | Ancient India and the Women Question: Brief Survey from the Earliest Period to Pre-Maurya Period | 14 |

| II. | Buddhist Perspective of Women | 27 |

| A. | Visibility of Egalitarian Concepts of Buddhism in the Images of Women in the Androcentric Literature (Therigatha) | 28 |

| B. | Misogyanous Literature | 42 |

| III. | Images of Women in Sanskrit Texts | 57 |

| A. | Gender Differnntiation and Contentious Feminine Voice of Sita in the Ramayana | 57 |

| B. | Devi Mahatmya (Markandeya Purana) and Mythical and Theological Tradition of Goddess Worship in Early India | 65 |

| IV. | Gender Identity: The Case of Queen Didda of Historical Kashmir | 87 |

| A. | Introduction | 87 |

| B. | Didda as Queen Consort, Regent Queen and the Ruling Queen | 92 |

| C. | Conclusion | 100 |

| V. | Gender in Inscriptions | 111 |

| A. | Women and Gender in Inscriptions | 112 |

| B. | Conclusion | 135 |

| Epilogue | 143 | |

| Glossary | 145 | |

| Bibliography | 157 | |

| Index | 167 |

Sample Pages