Akbar The Aesthete

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAF981 |

| Author: | Indu Anand |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | Urdu Text With Translitration and English Translation |

| Edition: | 2014 |

| ISBN: | 9788124607381 |

| Pages: | 316 (Throughout Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.5 inch X 9.0 inch |

| Weight | 1.80 kg |

Book Description

Mughal miniatures are a vivid account of the cultural, sociopolitical scenario of the Mughal era. Jalal-ud-Din Muhammad Akbar, the most powerful Mughal emperor, was a great aesthete and promoter of arts. Eminent Persian and Indian artists thronged his Royal Studio and were encouraged to paint numerous emotive miniatures of style and substance, communicating highly complex narratives. These miniatures are a beautiful manifestation of human expressions, vividly encapsulating moments of history for posterity.

This book combines the sources and methodology of history and art history of the Mughal era, and is an analysis of a select group of paintings of Akbar’s reign. The miniature paintings incorporate a wide variety of rich, vibrant and varied themes, ranging from durbar scenes, depicting Akbar in different moods and forms, the princes and nobles in their finery, hunting and battle scenes, elaborate scenes of royal births, construction scenes, ascetics, common man, and countryside scenes, to the flora and fauna. Individual analyses of these miniatures, shows the manner of their composition and the inherent value of their sociocultural content in a lively manner. These paintings became a passion and a diversion for Akbar, who had an innate aesthetic sense.

However, there are hardly any true-to-life paintings of women of the royal seraglio. This book thus attempts to cover some images of femininity, whether it is of Queen Alanquwa, Akbar’s mother, or of Madonna as sacred mothers, and women, per se, in different roles. These miniatures make one wonder how much these women contributed to the life of Mughal India.

This unique volume, having given transliteration and translation of the original Persian text of the miniatures, provides an insight into Akbar as an aesthete, and will help academics and laymen alike in appreciating the beauty and history of Akbar’s period.

Dr Indu Anand is an acclaimed educationist and academician. At present, she serves as the Principal of Janki Devi Memorial College, University of Delhi. She received Charles Wallace India Trust fellowship sponsored by the British Council to participate in Art History at Cambridge.

A Fulbright Scholar under Fulbright Visiting Specialist Program –Direct Access to the Muslim World –she has lectured in the US to promote Americans’ understanding of Islamic civilization and its history.

Dr Anand has achieved numerous laurels such as Women Achiever Award, Life Time Achievement Award, Women’s Achievement Award, Dr. Radhakrishnan Memorial Award, Mahila Shiromani Award, and Indira Gandhi Priyadarshini Award.

Her book Akbar: The Aesthete is a notable contribution to the study of social and material culture in the Mughal era through miniatures of that period.

India has a rich cultural past. Human civilization has travelled through several golden epochs in this land –the Mauryan, the Gupta and the Mughal periods had reached the pinnacle of the round progress, and the country had earned the sobriquet of the ‘golden bird’ by foreign travellers.

Akbar was undoubtedly the greatest monarch of the Mughal period. It was his astute leadership that unified the land into a tolerant social fabric, providing an enabling environment conducive for the growth of art and culture. As a result, architecture, painting, music and literature –all flourished under the royal patronage of this aesthete ruler.

Painting, and particularly the miniatures of the Akbar’s atelier, have inspired several academic studies from different perspectives. The present approach to assess Akbar as an aesthete provides a novel insight into the profound realm of Akbar’s paintings. The painstaking effort by Dr Indu Anand is a welcome addition in this area of study.

Much has been written about the mammoth contribution of the Mughal rulers in India. Among many other achievements in administration, economy and polity they have left their footprints on the Indian soil in the form of magnificent monuments and mesmerizing miniatures. Apart from the archaeological sources of historical information, Mughal paintings express the fact that the cosmopolitan urban exteriors of India have a rich past, that is intricately woven into the colourful miniatures.

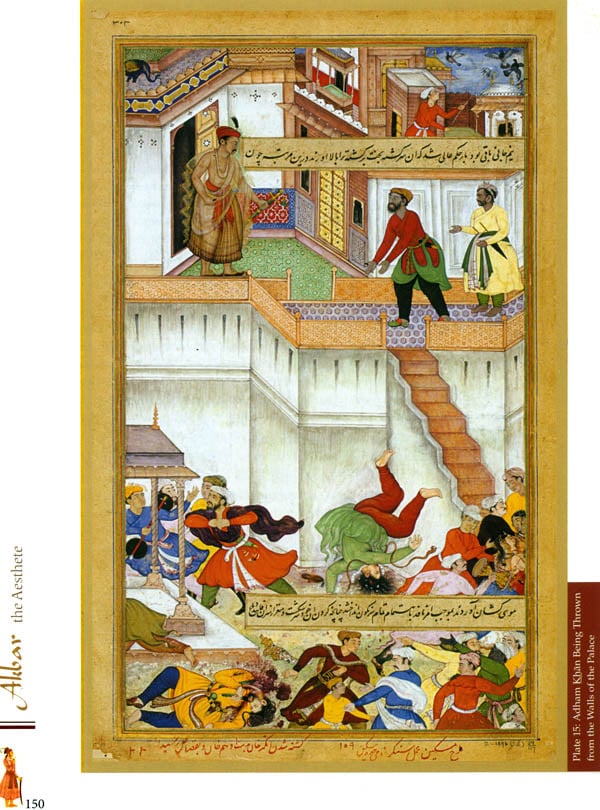

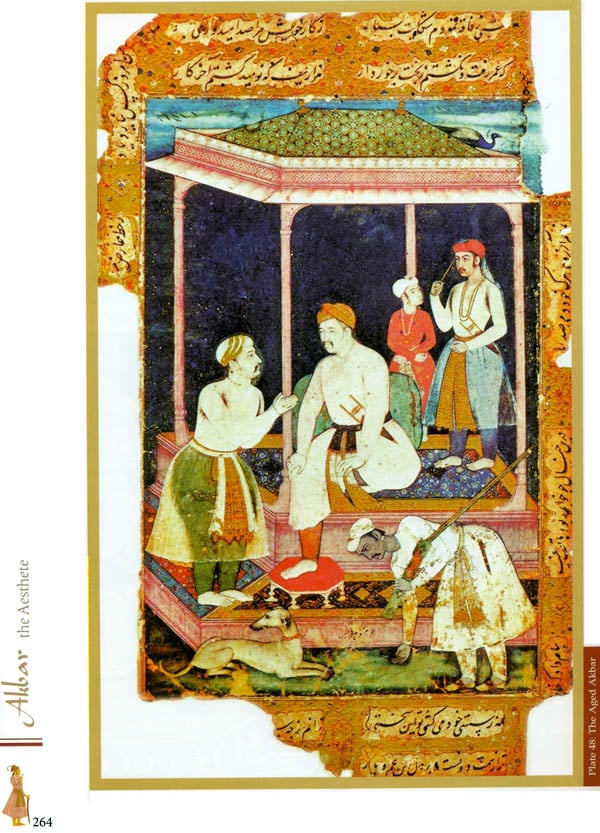

A large number of books on Indian paintings discuss Mughal art but do not concentrate on material culture. Often, a painting is not treated as a text, a close reading of which can enhance our understanding of material and technological dimensions of the contemporary society. It has the value of a historical record, conveying quite faithfully, what happened on a given occasion. In rendering the text, attempt has been made to give a complete transcript of the ideas from the original works like Akbarnama, Baburnama, Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri and Tutinama. A new dimension of transliteration and translation of the inscriptions of each miniature printed in the book makes it more rewarding. It is the hallmark of the civilizing process to constantly innovate and seek new uses for the already existing objects. It is, therefore, not surprising that something as emotive as the Mughal miniatures have assumed the powerful role of communicating highly complex narratives.

Reading other works on the Mughal miniatures, one began to feel that important contextual references of the Mughal miniatures pertaining to the material culture were not emphasized. Moreover, the Persian texts written within the miniatures have usually not been properly investigated for a deeper understanding of the sociocultural phenomena of the time. These insightful inscriptions are not just verses but explain the context of the paintings; sometimes giving us very precise and precious information.

Mughal miniatures of the sixteenth century form the focus of this study. In the individual analysis of these miniatures, the manner of their composition and the value of the sociocultural content which they furnish have been dealt with. Painting became a passion and a diversion with Akbar; who had an innate aesthetic sense. A royal atelier was established by Akbar where artists of Persian and indigenous origin were brought to work together who created a distinctive style and character, which became an integral part of Indian paintings.

The contents of these paintings have been particularly attended to, as they are the repositories of various forms of the contemporary material culture, the life of people, festivals, ceremonials, vocations, ornaments, furniture, aspects of gardening, and tools and technology used for various purposes like militia and buildings are profoundly portrayed in them. Nowhere else do we get such a clear view of the sociocultural life of the people in general as in the Mughal miniatures. The subject and style of the pictures are verily the true mirrors of the social milieu and mutual relations of the various constituents of the society of those times with paintings having a strong popular appeal, genre subjects, portrait studies of the ordinary people like labourers, one can re-imagine the past. The painter uses the resources of his palette in a riot of colours and calligraphy as the highest expression of beauty of form. The figures are decorated with gold work and embroidery. The credit for providing such as vivid representation of that society goes to the great emperor, imaginative builder and the connoisseur of arts, Jalal-ud-Din Muhammad Akbar. The works document and demonstrate the extent to which Akbar has been a prime mover and motivating force for the development of these exclusive forms of art.

The boom has been dived into two broad sections: first section is a descriptive section which contains an analysis of Akbar as an aesthete along with the depiction of existing material culture during his reign and the second section is an illustrative section containing reproduction of some impressive and important miniatures of Akbar’s reign, with their written accounts of what there once was, that reveals the breathtaking levels of sophistication and minuteness of the paintings.

This work is primarily based on an analysis of a select group of paintings of Akbar’s reign. One has tried to reconstruct the material culture of that period (1562-1605) on the basis of these paintings. Looking at the images incorporated here, one realizes how spectacular the Mughal court must have appeared to its contemporaries. During Akbar’s reign, the miniatures cast a magic spell on the viewer and are now the most valuable manifestations of the pageantry of the various Mughal court ceremonies as well as the rigours of the hunting. Art became more prolific and the subjects shifted to a grand scale.

Generally, historical and aesthetic studies of this period tend to concentrate on miniatures depicting martial and celebration scenes. But the present work analyses the ignored subject of the representation of women in situations other than amatory during the reign of Akbar. For instance, a rare painting showing the ceremonial bestowal of the baby Akbar to his wet nurses is unusual and particularly appealing in the miniature Akbar Given to His Nurse (Plate 2). The festivities in the harem on the birth of the royal heir and the rituals that were followed on this occasion have been depicted in great detail. The depiction of child bearing and rearing in the painting reveals the importance of the role of wet nurses to further the understanding of contemporary scholars about the little known facets of the lives of the court ladies and contemporary attitude towards women in general. This ought to be of great interest to scholars of this period, especially because of the relative paucity of information on this subject.

Another unusual painting is of the immaculate conception of Alanquwa (Plate 1). What is noteworthy in these paintings is the elevation of motherhood to an almost divine level. The father seems incidental, while it is the mother who becomes the procreator. This unusual claim to matrilinear ancestry is hardly ever discussed in scholarly works of historians. By including such rare paintings in this text, an attempt has been made to introduce fresh insight to scholarly discourse on the Mughal period.

As regards the sources for this compendium, the main Persian sources translated in English, the accounts of the foreign travellers and their memoirs, and a number of recently published articles in leading journals have been consulted in great depth.

The original intention was to analyse the paintings of the period of Akbar, Jahangir and Shahjahan, but the undertaking proved time consuming and more arduous than expected. Therefore, I decided to limit my study to Akbar’s reign, Akbar’s death seemed to provide a convenient halting place, as far as the style and substance of the miniatures are concerned. It was convenient to confine exclusively to Akbar’s reign, leaving his successors for a subsequent volume. An attempt has been made to focus on the aesthetic appeal of these paintings with minimal textual intervention, so that readers of all kind, academic to laymen alike, can appreciate the beauty and history of that period.

Research work on any particular topic is never complete in the sense of being a suitable model, and hence, is not always final. However, research endeavours ask and answer a number of questions in the area concerned, and this is exactly what has been attempted in this book. Though no efforts have been spared to make it as readable as my limited talents would allow, the miniature paintings still deserve to be explored in greater depth than is possible within the scope of this work. Writing this book has been like making a quilt, pieces were collected, cut up, rearranged and pieced together to create a new pattern. The work was also married by many interruptions. The process was, no doubt, arduous, even somewhat tedious with many beginnings and many conclusions. Each manuscript herein is accompanied by a brief text which is self-explanatory. It gives great pleasure and deep satisfaction to behold that at last my labour of love has seen the light of the day. I devoted to this work whatever little leisure remained there after my exhausting routine, involving the administrative work as the Principal of Janki Devi Memorial College, a constituent college of the University of Delhi.

For the successful completion of this volume, I am greatly indebted to a number of individuals and institutions. I thank them all for their timely help and co-operation they have extended. This book is based on the doctoral thesis submitted at Jamia Millia Islamia and builds further on research and teaching over the years. It is also a work of synthesis and interpretation, for which, one is heavily indebted to Prof. Som Prakash Verma of Aligarh Muslim University, whose thoughts inspired me much for what I hoped to achieve in this book. His pioneering works in the field of Mughal art have been a constant source of inspiration. His valuable suggestions in organizing the material and ideas proved to be very constructive as he very readily shared his characteristic zest and enthusiasm for the paintings. This publication would not have been possible without his enthusiastic support in accessing not only important articles and books but also lending certain original transparencies which were of great value.

Fruitful discussions with Paul Hills, Research Fellow, Birbeck College, University of London, UK, on the importance of colour pigments, colour perceptions, colour in decorative arts, and colour in textile, architecture and paintings were very fruitful. Interaction with Prof. Spike Bucklow, Research Scientist, Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge, UK, cleared my doubts about paintings in the context of conservation and restoration. The lectures of Dr Nigel Chancellor, working on British Indian history at Fitzwilliam Museum and also Dr Nicholas Friend, Director, INSCAPE, Queens College, Cambridge, UK, were very valuable.

I am, indeed, indebted to Dr Rajender Kumar, Associate Professor, Department of Persian Studies, Univeristy of Delhi, Ms Farah Adeeba, Assistant Professor, Zakir Hussain College, University of Delhi, and Dr Abdul Haleem, Associate Professor, Jamia Millia Islamia, for transliterating and translating the inscriptions. Special thanks are due to Farah Adeeba, for her beautiful calligraphic reproductions of the inscriptions on the miniature paintings. I also wish to thank Dr Neeru Mishra, Deputy Director, Indian Council of Cultural Relations, for her inputs.

The selected miniatures focus on the depiction of a wide range of material culture during Akbar’s reign. In order to reproduce the book, the kaleidoscopic scenes, the original collections of the miniatures preserved in the public libraries, museums and art galleries in the UK, USA and India have been used. Words are insufficient to express my gratitude and appreciation to Ms Divya Patel, who looks after the Indian Miniature Section of the Victoria and Albert Museum, for allowing me access to the rare collection of the Indian miniatures preserved there. I would like to express appreciation for the help from Ms Linda Parry, Deputy Curator (textiles) and Ms Ellen Morris, Sales and Research (academic publishing) of the Victoria and Albert Museum. I would also like to thank Mr David Scrace, Mr Bryan Clarke, Ms Jane Sargent, Ms Linda Clarke of the Fitzwilliam Museum, with whose help I got the rare opportunity to work on a few Hamzanama paintings, which were bequeathed to the museum by Mr P.C. Manik and Miss G.M. Coles through the National Collection Fund. I would also like to acknowledge the support of Ms Cory E. Grace, Image Management/Rights and Reproduction Assistant of the Freer Art Gallery, Washington DC, USA, for sending some original transparencies required for this book. Ms Jody Butterworth (Prints, Drawings and Photographs), Asia-Pacific and Africa Collection, British Library, London, graciously made available for viewing volume I of Akbarnama and a rare portrait of Akbar in original. I also want to acknowledge the efforts of Mr Aashutosh bhardwaja for providing rare paintings of Tutinama from Cleveland Museum of Arts. Sincere thanks are also due to late Dr S.P. Gupta, exchairman, Indian History and Cultural Society, for lending me the original negatives of some important miniatures from his collections.

I also want to acknowledge the help I received from the staff of the National Museum and would particularly like to thank Mrs Pratibha Parashar, Librarian of the National Museum, New Delhi, for her cooperation. I also gratefully recognize the co-operation extended by Rampur Raza Library, Rampur (UP); Salarjung Museum, Hyderabad; Bharat Kala Bhawan, Banaras Hindu Univeristy, Varanasi; Baroda Museum; Jain Vidya Sansthan, Jaipur; and Government Museum, Ajmer, in Supplying some research photographs of the paintings.

In completing this book, I have been fortunate enough in receiving financial support from the Charles Wallace India Trust, who provided necessary funds for me to attend an Art History course at Cambridge, UK, where I had one-to-one interaction with the various experts in art and paintings. I also gratefully acknowledge the foreign travel grant by the Indian Council for Historical Research (ICHR) for the trip to UK. I would like to thank Adam J. Grotsky and United States India Education Foundation (USIEF) for granting scholarship to visit the United States under Fulbright Visiting Specialist Programme to promote a greater understanding on Islamic Culture and Society based on my findings from Mughal Art. My Interaction there with Marv Mutzenberg, Professor of World Religion, greatly enriched the final stages of writing the monograph.

Finally, I would like to thank my family, Ashok, Amit, Karishma and Aanya Anand. Sonia, Vaibhav, Akshat and Ameya Aneja for putting up with lost weekends and endless late night discussions, as I struggled to complete my work.

I have drawn with all the care and fidelity, of which I am capable, the materials of which the book is composed. I can confidently assert that I have set down nothing in these pages which have not been derived from the works of acclaimed authors or from the letters of persons worthy of credit. Once again I wish to express my deep gratitude to all of the abovementioned people and my friends for the generous help that they have extended to me. But these names of various authorities do not mitigate my responsibility for errors or shortcomings in the book; I am solely responsible for all or any one of them.

This book is an interpretation of Mughal paintings during the reign of Mughal emperor Jalal-ud-Din Muhammad Akbar. These paintings travel through his life and history. In this work, I have perceived Akbar as an aesthetician. Through years of research on the subject of Mughal History and Art, I reached the conclusion that it was Akbar and his thoughts, ideas and personal beliefs that led to the formation of the Mughal aesthetics of the sixteenth century. Heritage can be interpreted in different ways. Different scholars, over a period of time, have differently defined the Mughal aesthetics of the sixteenth century. For some this aesthetics lies in the monumental architecture of the time; for others it is in the textiles; and while some may find Mughal aesthetics in the poetry and cuisine of the time; many more have found it in the miniature paintings of the period; and while for some aesthetics can be found in the simple Persian term Mughal itself. But, in this work, I explore what forms the Mughal aesthetics of the Akbari period – the written history of the period, Akbarnama, being largely connected with book illustration. Composed by Abu’I Fazl and conceived by Akbar himself, the miniature paintings therein are marked by great finesse.

These paintings are a beautiful manifestation of human expression and vividly encapsulate moments of history for posterity. The ascendancy and vitality of the Mughal art of Akbar’s period can be gathered from its evolution into a unique genre of miniatures manifesting an eclectic lineage from Persia, India and Europe. These miniatures provide a stunning wealth of information about the Mughal court and its material culture. Perhaps, the royal patrons of art in Mughal India realized this and essentially used the narrative art ensuring that all important events of the time were frozen forever by the greatest artists of the imperial courts. We are heavily indebted to the artists and their patrons who left for us vivid pictures that often tell us things that were never captured in words. We have a rich inheritance of these vivid images of courts in session, battles being won or lost, royal hunts and the everyday life. In the Mughal imperial and aristocratic households, a heightened sensibility prevailed towards the imaging of the court culture, the purpose of which was to preserve its history in all its glory. A clearly defined literary and artistic propriety was followed in the preparation of these narrative manuscript productions, imbued with lively colours, gestures and movements. Illustrations and paintings led to the formation of libraries as separate entities in the Muslim world, a traditional institution taken seriously by the Mughals. These libraries were the monuments of a culture that treasured world, built by rulers who had the resources to enshrine it. Akbar’s library was a significant benchmark of the overall social well-being of the society.

Mughal* was the dynastic name Babur, grandfather of Akbar, chose for himself and his family as they were to become the new rulers of the land beyond the Indus, Hindustan. Coming from a lineage of Chingiz Khan (Genghis Khan) and Timur, Babur and his descendants were able to create home for themselves in this part of the Indian subcontinent. But, among all the Mughal rulers, it is Akbar who is considered as the greatest ruler of all, not only because of his political policies but also for his personal beliefs and ideals. And it was these personal beliefs and ideals of Akbar which led to the manifestation of the aesthetics of his era: the miniature paintings and Akbarnama. The imperial Mughal school’s visual records of the sixteenth century are the richest and the sincerest expressions of the life of the people. Their vocations, etiquettes, ceremonies, festivals, daily chores and social relations unfolded in these paintings exhibit the artist’s vivid and close observation of life around him. Cultural history, to a great extent, can be reconstructed on the basis of literature and artistic achievements.

In the case of the Mughal period, we find that the chronicles have seldom taken note of the cultural panorama of the times these paintings depicted. In the absence of textual evidence, the paintings from the Imperial Mughal school present before us a very vivid picture of the rich cultural life. in this book, I try to showcase how, under the patronage of Akbar, arts became radically innovative and, also, how profoundly he altered the character of miniature painting. The use of pictorial images to reconstruct the material culture is perfectly valid as the writings of Abu’ I Fazl’s Akbarnama, which is the most celebrated official document of Akbar’s time. They are the collective constructs of a society and are loaded with meanings like any other contemporary source of information on literature or architecture. The images are an important repository of the contemporary society, culture and the natural surroundings.

The Mughal miniature paintings have a wide range of rich, vibrant and varied themes, ranging from durbar scenes, depictions of the emperor, the prince and the nobles in their finery; hunting and battle scenes; the elaborate birth and marriage scenes of the Mughal royalty; building construction scenes; ascetics; common people; and the flora and fauna of the time. The themes also concern a variety of subjects such as the mannerisms, customs, private and public life, social attitudes, personal ambitions and aspirations, dresses, various kinds of entertainment, different musical instruments, aesthetic sensibilities, other objects of material culture and, above all, the pomp and grandeur of the imperial court scenes. The notable skill of the artist lay in his ability to depict the lengthy events, sequences or passages into a single visual.

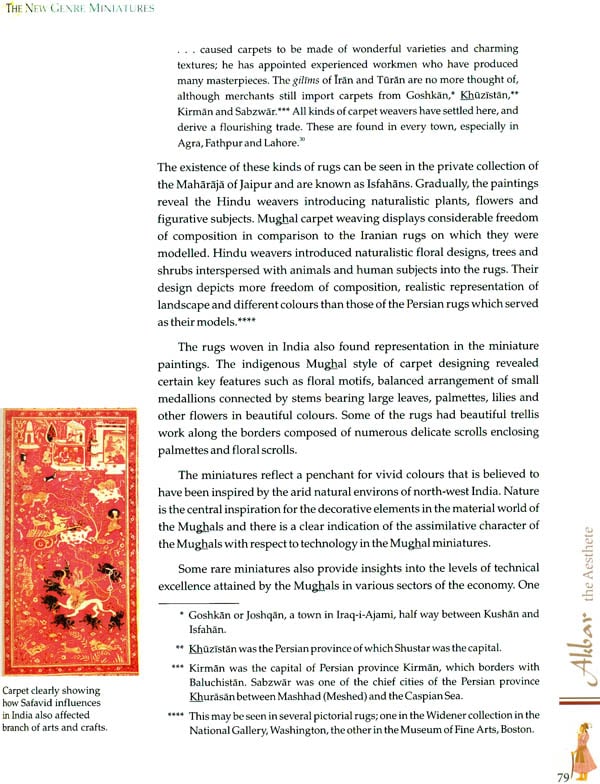

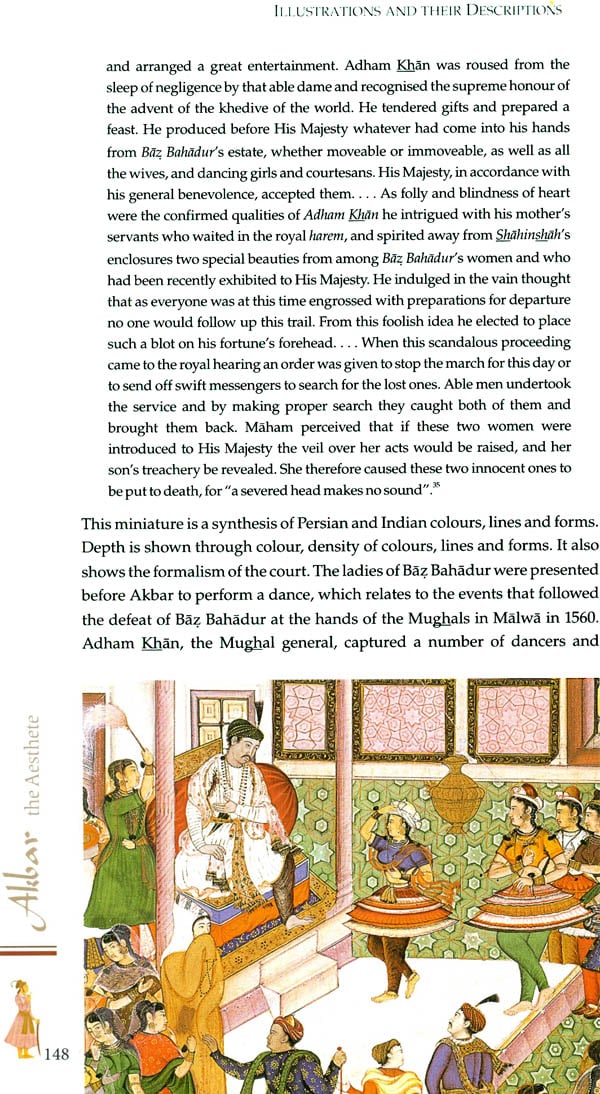

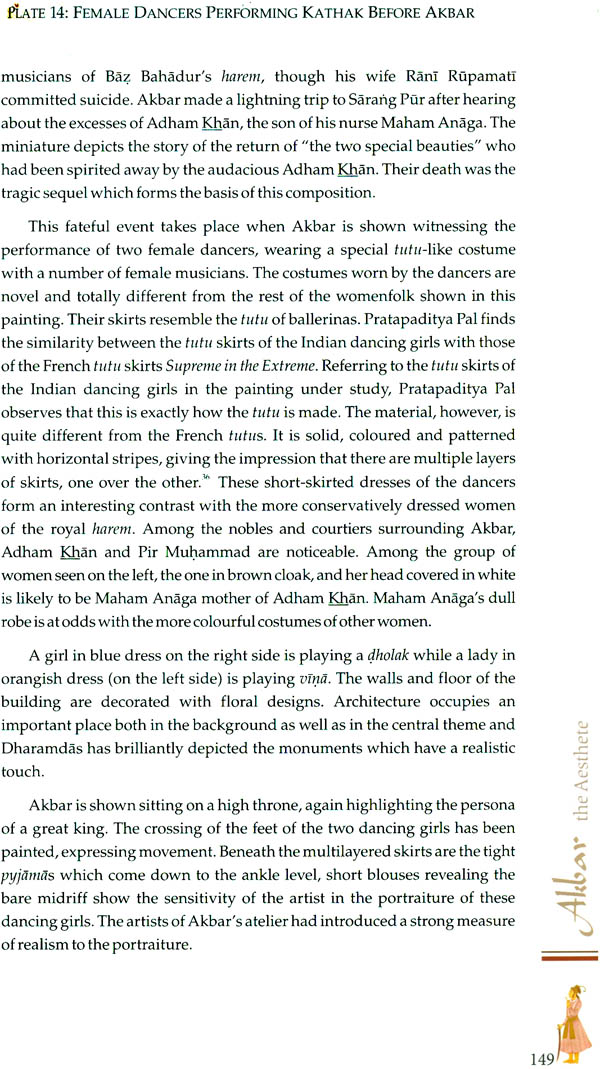

The Akbrnama paintings represent different kinds of royal insignia, spreads, carpets, utensils, costumes, furniture and the miniatures depicting battle themes, various arms used by the foot soldiers and the cavalry. The shape and mechanism of the matchlock of the sixteenth-century India are very well depicted in miniature entitled Bairam Khan watching Akbar Learning to Shoot, Govardhan, c. 1604, Akbarnama, miniature from the British Library (Or. 12988, f. 158a). In the same way, the durbar scenes give a vivid impression of the pomp and circumstance of the Mughal court and of the personalities of the great men of the time. Paintings like the celebrations held at the time of Circumcision Ceremony of Akbar’s Sons (Plate 9) depict customs and practices observed during the Mughal period. The vivid narration of the painter is sometimes the only source of information for cultural historians on these issues and themes. The astrologers, depicted in the illustrations (birth scenes) with their instruments and time-reckoning devices of the medieval period, are another important genre. There is an important section on painting in A’ in-i-Akbari (the statutes of Akbar), a part of Akbarnama which was completed in 1597-98. It presents Akbar’s views on arts in general, and the Persian paintings in particular, especially the establishment of an atelier under Mir Sayyid Ali and ‘Abdu’s Samad. This text reveals the spiritual and philosophical depth of beautiful images. Akbar’s comprehensive and mystical view of the world is also well demonstrated. Abu’I Fazl also gives a list of the celebrate painters of the time and their field of specialization.

The painters undoubtedly created great traditions in portraiture in the recording of court events and depiction of animals, birds and the nature. The Mughal era paintings present a semblance of appearances, the imparting of grace, correct observation of proportion and the action of feeling on forms, of fidelity of representation and also knowledge of the correct technique. A careful study of the various gestures depicted in the Mughal miniature paintings reveals the different social rankings which prevailed in the Mughal durbar, hence an attempt has been made by the author in the present study to decipher some of the important gestural codes which existed in the Mughal era.

The selection of miniatures in this book has also attempted to cover some images of feminity. There are hardly any true-to-life paintings of women of the royal seraglio. Among the images of the ideal family is the image of the mother as the sacred mother represented in the painting Rejoicing at the Birth of Akbar’s Son Salim, by the artist Kesav and Dharamdas (Plate 6). One is expected to be skeptical about the veracity of the paintings of queens and princesses. The objective of present observation, vis-à-vis images of women, is to discern image of feminity. When one finds these women one is amazed to see how much they contributed to the life of Mughal India. Very interestingly, these women came from different backgrounds; some were Rajput, others Persian and some even mythical. Represented as mothers, wives, daughters, as also gifts and something that can be possessed, respected and admired at the same time. As the Mughal artistic activity symbolized the Mughal grandeur, the women represented in it also became grand. Their social roles were particularly marked and they appear as icons of perfection and ideal feminity that pertains to women’s morally right behavior which conforms to high standards of chastity. Image of a female was seen to be functional only in so far as it was supposed to achieve the noblest aim of motherhood and operational only in so far as it worked for family honour and the household. These images are received from the literature of the period. They convey how the patriarchy restricted control and channelized women’s lives for its purpose in the face of grossest forms of transgressions of societal norms by women. Abu’ I Fazl, the official historian and a close companion of Akbar, delineating the emperor’s descent as Akbar wanted it to be seen, reveals for us the ideal of medieval feminity and image idealized and exalted. Abu’I Fazl also traces Akbar’s lineage back to the semi-mythical queen Alanquwa.*

The elaborately detailed history of his master’s life, which Abu’I Fazl had left to the posterity, is an important source for the study of medieval history. The most vivid of these histories is Akbarnama. The Akbarnama paintings, with vibrant colours and myriad details, are extremely appealing. Susan Stronge has rightly commented:

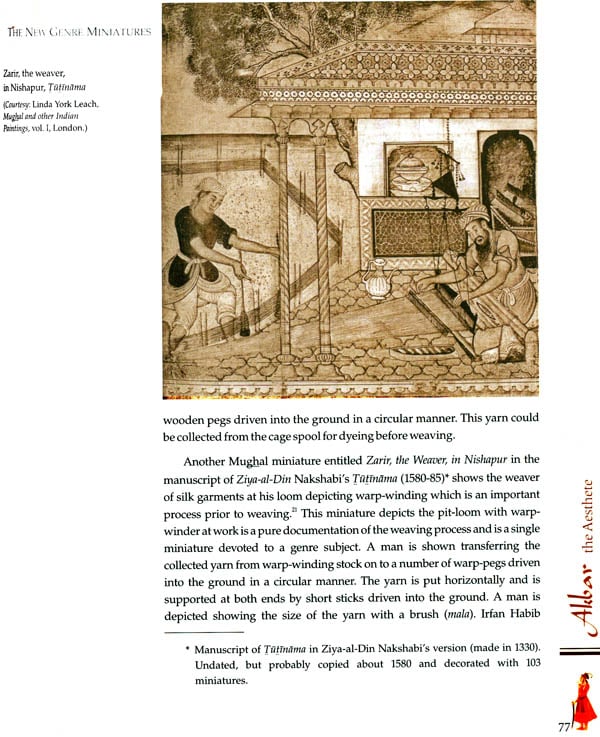

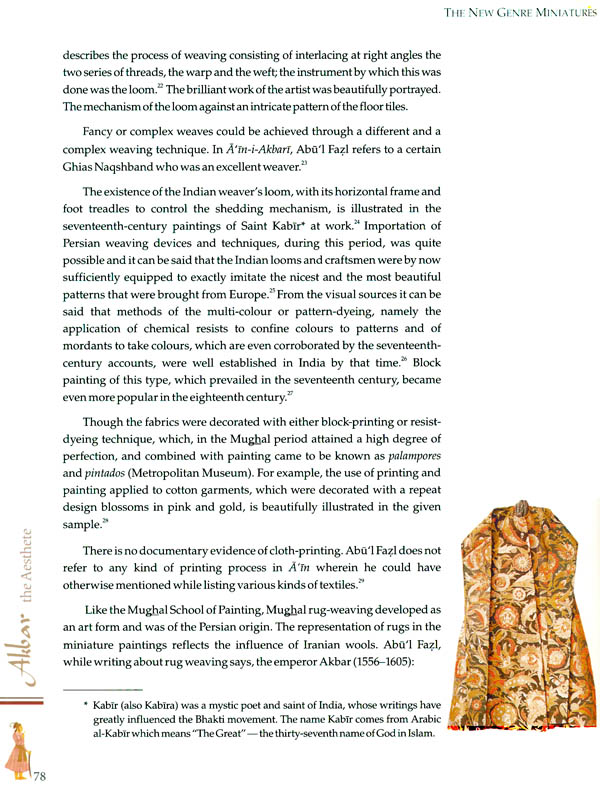

Claims of Akbar’s illiteracy were, however, only true to the extent that he never wrote himself. Later in life, he loved to have books read out to him and was an excellent judge of calligraphy. After a spate of spectacular conquests and military successes, Akbar’s rapidly won fame as conqueror was, however, rivaled by his acf Dasthievements as a patron of art and culture with the preparation oan-i-Amir Hamza illustrations in the 1560s which had laid the foundation of the Mughal school of painting. This text carries a set of 116 superb miniatures and is now preserved in the archives of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Three examples from this manuscript: Gardners Beating Giant Zamurood Shah Who is Trapped in a Well and Kausaj Finds Zamurood Sleeping (Plates 29a, b) have been analysed. Few illustrations inform us about the historical events like Rejoicing at the Birth of Akbar’s Son, Salim (Plate 6). Abu’I Fazl’s narrative is important, as it described the contents of the paintings and a number of illustrations were drawn directly and exclusively from his own narrative, contributing to the material culture of the period-by showing the architecture of various cities and fortresses; the costume of courtiers; attendants; and the representation of different professionals, e.g. Weavers at Work (Plate 37) shown beating cotton, stretching yarn and working with treadles on loom. This is a very clear depiction of the evolution and process of weaving technique in the sixteenth century, as the use of the treadle, i.e. flat foot board being operated by feet, deserves special attention.

| Foreword | v | |

| Preface | vi | |

| List of Plates | xiv | |

| Abbreviations | xix | |

| Introduction | 1 | |

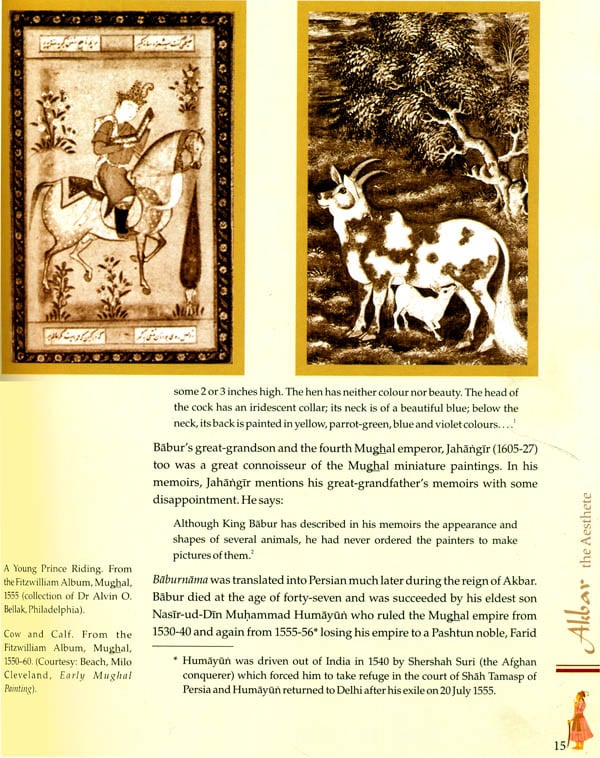

| 1 | Chapter I: Akbar the Aesthete | 14 |

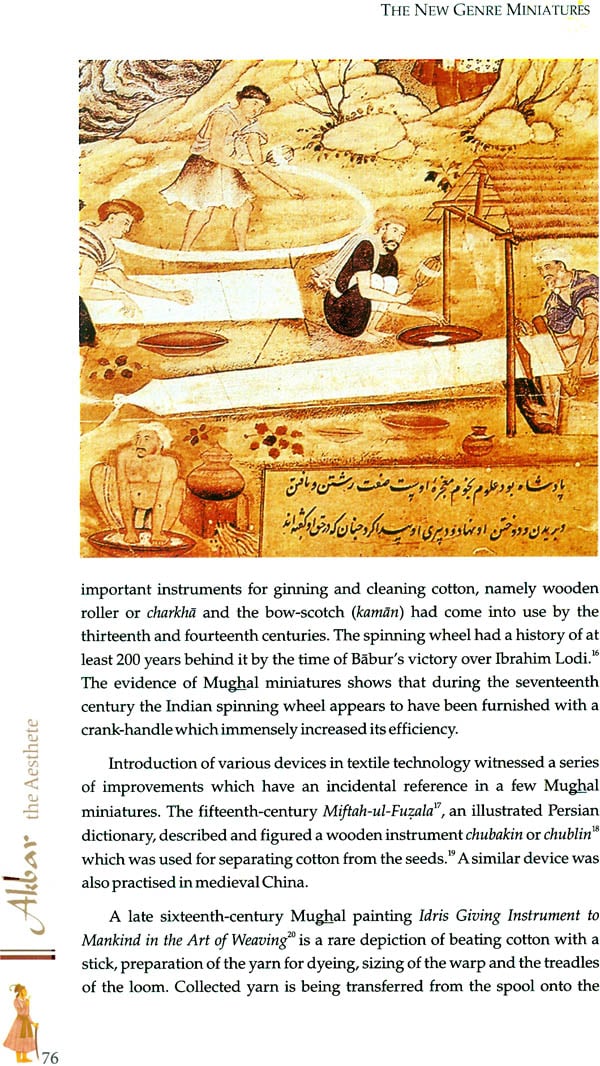

| 2 | Chapter II: The New Genre Miniatures | 59 |

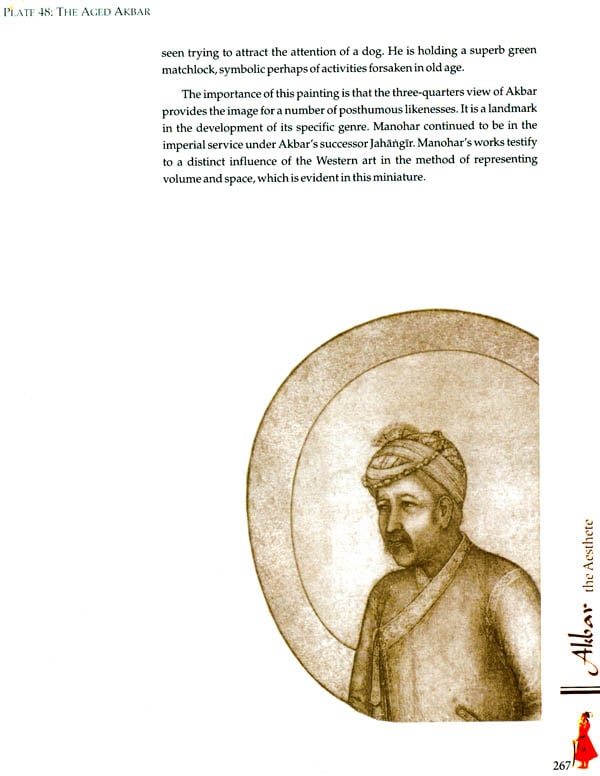

| 3 | Chapter III: Illustrations and Their Descriptions | 89 |

| Annotated Glossary | 271 | |

| Glossary | 275 | |

| Bibliography | 279 | |

| Index | 288 |