Bonds Lost (Subordination, Conflict and Mobilisation in Rural South India c. 1900-1970)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAZ339 |

| Author: | Gunnel Cederlof |

| Publisher: | Manohar Publishers and Distributors |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2021 |

| ISBN: | 9788173041938 |

| Pages: | 296 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 8.80 X 5.80 inch |

| Weight | 450 gm |

Book Description

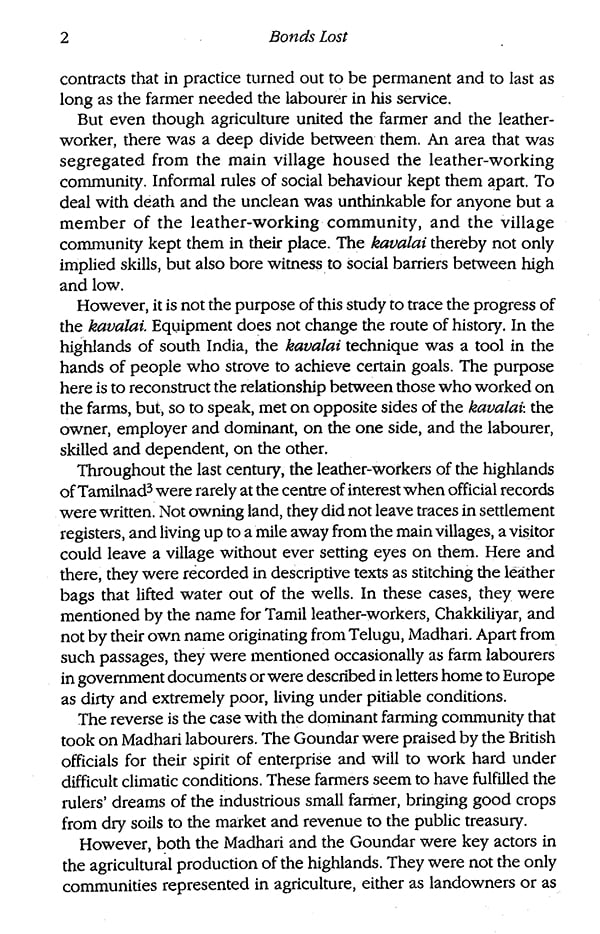

Social relations in rural south India have often been studied from either a perspective of labour and economic exploitation or one of dominance and subordination in terms of caste or exercise of political power. In Bonds Lost, the author argues that relations between landowners and agricultural labourers cannot be understood without taking account of both the economic and the social logic of the relationship.

From a variety of government, mission and oral sources, the author analyses the transformation of rural social relations in the central parts of the highlands in today's western Tamil Nadu between c. 1900 and 1970.

Throughout the expansion of commercial crops in agriculture, in particular of the cultivation of cotton, the farming community of Goundar and the agricultural labourers of the Madhari leather-working community have been closely related to each other. There has been a mutual, however, uneven dependence between the two; the farmers being dependent on the skills of leather workers to manage the irrigation, the Madhari equally dependent on the farmers for their own survival.

Until the 1930s, competition for labour scaled up in the region and agricultural labourers were increasingly tied by advance payments to work for a farmer. On account of this, economic expansion gained support and social control was upheld. However, even after preconditions had been made available to achieve a more profitable farming by replacing the permanent by casual labourers, a substantial, permanent labour force was still employed on the farms. In the late 1930s and 1940s, kinship-wise mobilisation among the Madhari labourers to convert to Christianity was met by strong and sometimes violent resistance. Every movement they made to break with Goundar authority was seen as a threat. Thus, during the decade, social rationality was given priority over economic rationality by the farmers. A severe six-year-long drought put an end to this situation.

Gunnel Cederlof is Professor of History at the Linnaeus University, Centre for Concurrences in Colonial and Postcolonial Studies, Sweden. Her research spans modern Indian and British imperial history, and environmental and legal history. She was Professor of History, Uppsala University, and has taught at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden.

Among her publications are Founding an Empire on India's North-Eastern Frontiers, 1790-1840: Climate, Commerce, Polity (2014), Landsapes and the Law: Environmental Politics, Regional Histories, and Contests Over Nature (2008 and 2019), At Nature's Edge: The Global Present and Long-Term History (2018 with M. Rangarajan), Subjects, Citizens and Law: Colonial and independent India (2017 with S. Das Gupta), and Ecological Nationalisms: Nature, Livelihoods, and Identities in South Asia (2006, 2012 with K. Sivaramakrishnan).

We were standing at the top of the steps admiring the front of the large building. The warm, south Indian night embraced us as the powerful Goundar landlord related his father's and grandfather's history. It was clear to anyone listening that this was their village in the deepest sense of the word. It had been a pleasant evening, the landlord had been generous with his time, and, as we stood talking, we could hear the women in the house preparing an evening meal.

Suddenly, looking out towards the front gate, we observed someone moving. The man had been standing there for quite some time, and now that the landlord set eyes on him, he slipped out of his shoes and walked across the front yard towards us. Both landlord and visitor were dressed in similar western styles and could easily have been taken for government employees in the streets of Tiruppur. Here, in front of the house, the man approaching kept his head low. As he stopped in front of the steps, we came to stand four or five steps higher up, looking down at him.

The visitor was a leading person of the Madhari community of the village, the community that had laboured in the Goundars' fields for generations. He was the real host for our visit that night but he had been away when we had arrived at his house. Now he came to enquire about his guests. Would we honour him by sharing a meal with him and his family in his home? The landlord, turning his back to the man and pointing with his left hand; asked, 'Do you want to go with him or stay where you are?'The irresolution I felt in making the decision was later that night replaced by a growing understanding of history. I am part of it, it is part of me. Travelling to the other side of the globe does not change this fact.

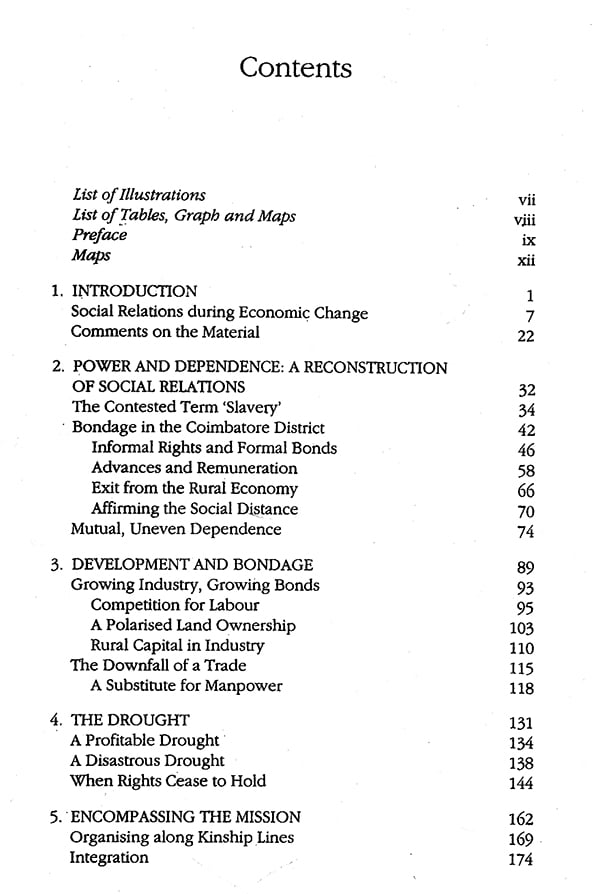

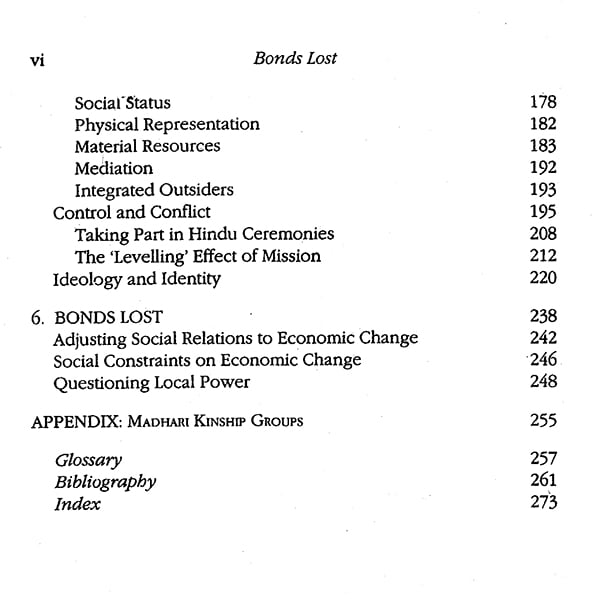

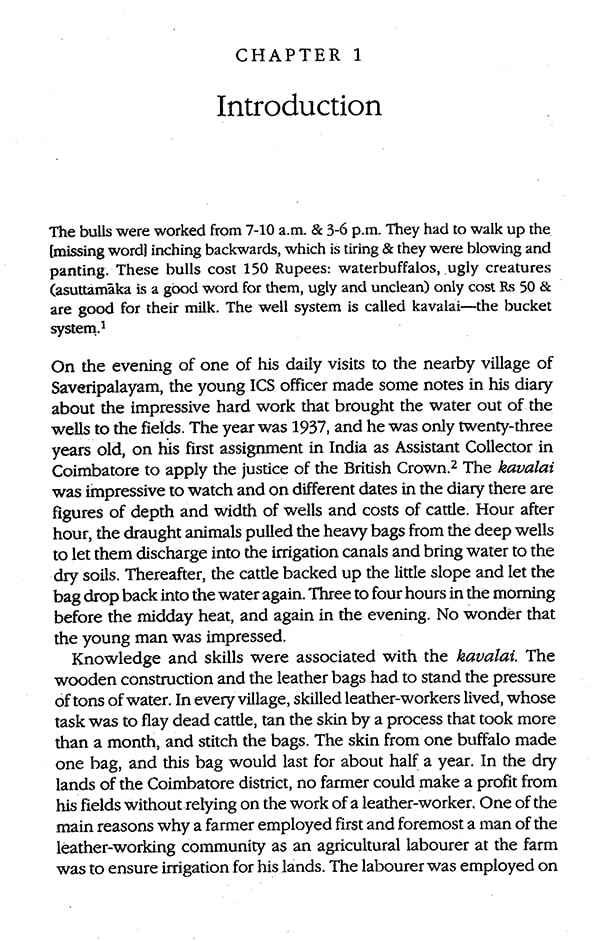

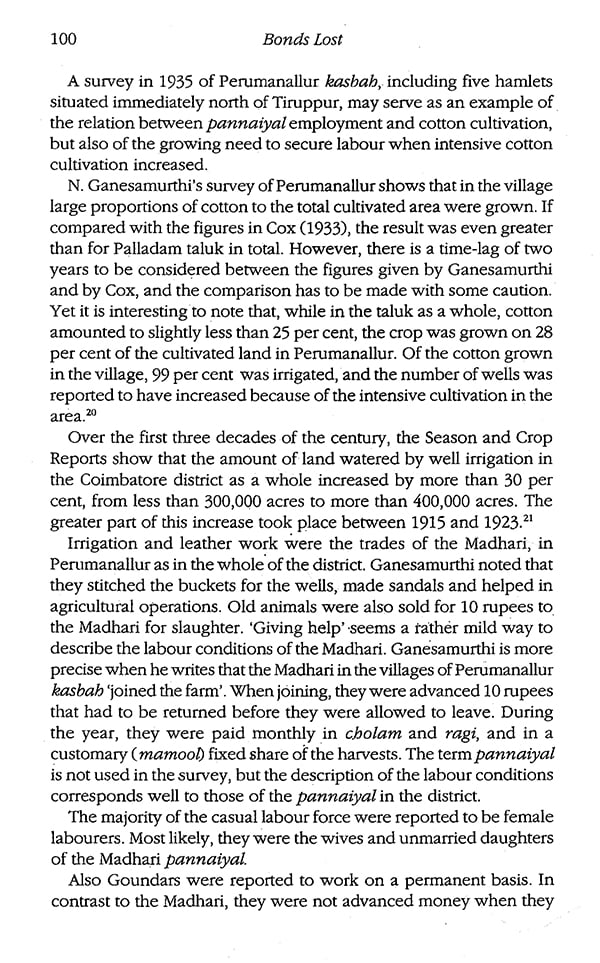

**Contents and Sample Pages**