Business Legends

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAF947 |

| Author: | Gita Piramal |

| Publisher: | Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1999 |

| ISBN: | 9780140271874 |

| Pages: | 674 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 630 gm |

Book Description

G.D. Birla, J.R.D. Tata, Walchand Hirachand and Kasturbhai Lalbhai-four pioneers who were a not afraid to think and plan big, at a time when Indian industry had to compete fiercely for market share against the multinational of the day. Together, they would lay the foundations for the golden age of Indian industry from 1951 to 1962. In this best-selling book, the closest look at these legends this far, Gita Piramal compellingly brings alive their ambition and achievement.

BUSINESS HISTORY HAS always fascinated me, so much so that I invested eight years for a doctorate in it. Unlike other freshly minted Ph. Ds, however, I never got round to publishing my research. This was partly because of my desire to use it to compile—some day in the nebulous future—an annotated bibliography on the economic history of Bombay. Such a project would be far more useful than my dissertation, I felt, yet the dissertation was the foundation for a ‘more useful’ book. I resolutely shelved years of hard labour waiting for the right moment to arrive.

The moment came unexpectedly and I was quick to seize it. While chatting with other business historians, I heard about the Lalbhais’ treasure trove of old letters. The entire collection of Kasturbhai Lalbhai’s correspondence had been carefully stored— and the family was willing to allow me to rifle through them. Thousands of letters which no one had ever seen! I felt as Aladdin must have as I unpacked the red cloth potlas into which the files were stuffed. Postcards from Mahatma Gandhi, the grey hand-made silk paper wedding invitation of Rajiv and Sonia Gandhi, angry exchanges between Kasturbhai Lalbhai and he income tax authorities, the arbitration papers dividing the brothers’ assets, a son’s sorrow over his mother’s illness—story came to life in front of my eyes. The added advantage was that my training and reading enabled me to grasp the contents of the letters, and to sift the trivial from the critical.

I am fascinated by people and their legacies, but that doesn’t explain why today’s manager should bother to read, about yesterday’s entrepreneurs. After all, business at the threshold of the millennium is quite different from what it was fifty years ago. The environment has changed, as have the products and the pace of response. With nothing in common, what possible lessons can there be in the lives of four long-gone businessmen to justify time spent reading these pages?

Quite a lot, actually. Because the similarity between India just before and after independence and India in the nineties is far greater than between India in the eighties and the nineties.

If this proposition seems rather extravagant, consider this:

During the pre- and post-independence period, several entrepreneurs outperformed the rest, producing products and services which were globally competitive. Four in particular— G.D. Birla, Walchand Hirachand Doshi, Kasturbhai Lalbhai and J.R.D. Tata—are particularly outstanding for their contribution to Indian industry.

In a 1939 listing of India’s biggest business houses—both local and foreign—the Tata Group topped the roll of honour with assets of Rs. 62.42 crores. The second largest, Martin Burn, was a poor second, with assets of a mere Rs. 18 crores. This was a formative age for the other three businessmen profiled here. The Birla group, at 13th place, owned assets of Rs. 4.85 crores, the Lalbhais had half that with Rs. 2.33 crores and ranked 30th. Walchand, in fact, was bigger than the Birlas at that point of time with assets of Rs. 3.66 crores in Scindia (ranked 17th but where he had three partners) and another Rs. 2.61 crores in his own group (25th).

By 1969 the picture had changed dramatically. The white burra sahebs had more or less abandoned their companies to Indians. According to the Report of the Industrial Licensing Policy Inquiry Committee, the Tata group remained India’s biggest business house with assets of Rs. 505.36 crores, but the Birlas had leapfrogged other groups to become the second largest in the country with assets of Rs. 456.40 crores. JRD and GD were running neck and neck despite the Tatas’ century-long advantage. This was a growth period for the Walchand group as well and they jumped to 9th rank with assets of Rs. 81.11 crores—and this didn’t take into account Scindia’s Rs. 55.99 crores as the group had parted ways with the shipping firm by then. Had they managed to retain control of the shipping giant, the Doshis would have hauled themselves to 4th place. At 18th place with Rs. 51.20 crores in assets, the Lalbhais hadn’t done too badly either.

What made these men special? G.D. Birla, with his modern mind, was a rare man who dared to challenge old traditions from a very young age, a thing unheard of in the conservative Marwari community. In the turbulent politics of the time, Birla liked to portray himself as an ambassador, mediating between Gandhi and the British, but his true contribution to India was industry. He and his three brothers built factories in the wilderness, factories which created wealth for local economies as well as the nation.

Most of G.D. Birla’s actions were carefully thought out and executed. He rarely acted on gut instinct. Walchand Hirachand, on the other hand, wanted to run before he could walk, carped his critics. He built an aircraft factory years before India could produce a diesel engine. He built a shipyard which the Nehru government considered too important to remain in private hands. If Bombay has drinking water, it is because of the huge pipelines he laid. When he became a building contractor, his father was convinced that Walchand would bankrupt the family. He took exceptional risks, but he built the foundations of modern India.

Waichand Hirachand’s main theatre of operations was Maharashtra. Another regional entrepreneur with a difference was Kasturbhai Lalbhai, who founded one of India’s largest textile dynasties. His skill as a negotiator first came to light when he crossed swords with Mahatma Gandhi. The year was 1917 and Kasturbhai was barely twenty-six. Despite his youth and the fact that his mill was then one of the smallest in Ahmedabad, his peers invited him to represent them in ending one of the most famous strikes in labour history.

While Lalbhai was carving a name for himself as a negotiator, T.R.D. Tata was busy writing his own chapter in the same book. Sick in bed, JRD drafted a labour manifesto for the huge steel works at Jamshedpur, a manifesto which ushered in new harmony into Tisco’s strike-torn history. Better known for his aviation feats and Air-India, little is known about Tata the businessman who shaped Tisco’s career for over half a century, which is why this book tries to look beyond Air-India to his other achievements. He surrounded himself with brilliant men, men who built companies such as Telco and Tata Chemicals. But did JRD realize his true potential?

In their drive to build huge empires, these men faced all kinds of challenges. From the way they tackled the obstacles facing them, today’s managers can learn how these savvy strategists warded off MNC attacks, extracted the best out of labour, and used the power of lobbying through associations to level the playing field.

In an era when data was hard to find, they had the answers. Given the paucity of trained professional economists on whom they could rely, they took to writing themselves on economic subjects. For decades, the Tata group’s pocket-size statistical handbook was the best source of general economic information. Few could argue against Walchand’s figures on shipping, construction and cement industries, or Kasturbhai’s knowledge of the textile industry. When men like GD, JRD, Walchahd and Kasturbhai spoke, people listened. They routinely published detailed reports which were then used by associations such as FICCI, the Indian Chamber of Commerce and the Indian Merchants’ Chamber.

But does that make them legends? What is the difference between a leader and a legend and what additional attributes does a leader need to qualify for ‘legendary’ status? Oddly enough, dictionary definitions are somewhat vague on the subject, though most of them agree that technically a legend is a story or collection of stories of a saint’s life. I doubt if the four businessmen featured here are perfect, but I do consider them legends. Why? Legends become legends not because of their personal triumphs but for the impact their work and effort have on hundreds of other lives. A trader thinks of today’s profit, an industrialist looks at tomorrow’s balance sheet, but a legend thinks of the next generation.

Indian corporate lore is full of awesome stories of remarkable businessmen who have established powerful dynasties. There are marvellous rags-to-riches stories such as that of M.S. Oberoi (b 1900) who made a mark for himself hoteliering, or of Mafatlal Gagalbhai (1873—1944), the Bombay textile tycoon who started his business career selling cut-pieces on street pavements. There are hundreds of inspiring stories like that of H.P. Nanda (b 1917), the doughty refugee from Pakistan who built Escorts and then fought off a messy takeover bid for the tractors-to-motorcycles company; or that of Laxmanrao Kirloskar (1869— 1956), who lovingly encouraged roses to flower among cacti while building the group’s engineering companies. There are stories of nationalist-businessmen like Jamnalal Bajaj (1889— 1942); of fine technocrats like Ardeshir Godrej (1868—1936) the locksmith; and of customer-focused service-providers like T.V Sundaram Iyengar who went on to promote the TVS group. Each of these offers fascinating insights about how to make money. But legends have to have a vision beyond the accumulation of personal wealth.

I selected G.D. Birla, Walchand Hirachand Doshi, Kasturbhai Lalbhai and J.R.D. Tata for this book because I felt their entrepreneurship styles were a cut above the rest. To understand fully their contribution to Indian industry, we have to assess them in the context of their times.

India was a jewel in the British crown, but most Indians were too poor to afford shoes. Even JRD’s father went barefoot for the first fifteen years of his life. We’ve forgotten the famines, the riots and the plagues which India suffered. When the British left, they proudly boasted that they had built the world’s tenth most industralized nation. But we were a colonial economy and it was heavily skewed in favour of the export of agricultural goods and raw materials, and the import of finished goods. India made very few products—almost everything for the past century and more had been imported. At this time there were thousands of Indian businessmen who used the shortages for private gain and profit. But not these men.

Admittedly, this view is contrary to public perception, which regards most businessmen, particularly G.D. Birla, as monopolists. But there is sufficient evidence to show that this was not the case. In fact, the four men profiled here went out of their way to encourage entrepreneurs to start new businesses. As G.D. Birla once said, ‘Any fool can establish a business when there is a boom. But it is during a period of depression that one’s ability to establish and run a business is really tested. I therefore appeal to businessmen not to be disheartened but to learn to take risks.’* This was not mere rhetoric. When small businesses ran aground, these four men did their best to help.

G.D. Birla encouraged other Indian businessmen to enter the jute business along with him. Walchand Hirachand bailed out small Indian shippers wherever and whenever he could. Kasturbhai Lalbhai helped other millowners in Ahmedabad to improve the performance of their cotton mills and the quality of the cloth they produced. In Jamshedpur, J.RD. Tata developed satellite empires around Tisco. They fostered a community spirit even though it meant creating new rivals and more competition for themselves. It was only after the government grew antagonistic to big business did the atmosphere get vitiated in the seventies and eighties.

This is one reason why I refer to these four men as legends. There are three more.

Business legends don’t take the easy road to prosperity Birla, Walchand, Lalbhai and Tata hacked roads through jungles, built factories in villages, transformed barren tracts of land into profitable assets, and inculcated the industrial ethos into the mindset of peasants. They built large industrial complexes which were as ambitious at the time as Ambani’s Jamnagar refinery is today. G.D. Birla’s aluminium smelter at Renukoot, Kasturbhai Lalbhai’s Atul chemical complex, J.R.D. Tata’s Telco plant at Pune and the extensions at Tata Steel, Walchand Hirachand’s shipyard at Visakhapatnam and the Premier Auto plant outside Bombay are testimony to their grit and vision. In most cases, they pioneered the industries in which they operated.

Nor did they boast about their victories (with the exception of Walchand Hirachand perhaps!). As JRD once modestly put it, ‘I am a businessman. I was born in business. I was born in industry. I was trained in it, and I believe that the future of this country lies in economic development. Therefore my primary role is that of a businessman. I’m not boasting about it and I don’t deserve credit for it.’ Nonetheless, the companies they established, the complexes they constructed are the foundation on which the economy rests today. Few factories on such scales came up in the seventies and eighties. In short, these are the men who built Nehru’s temples of modern India.

A third reason for bestowing legendary status on these four men is because of their commitment to education. All four invested heavily in the tools for progress: schools and colleges whose alumni serviced the ‘temples’ both in the private and public sector. JRD founded several premier institutions such as the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, the Tata Institute of Social Sciences and even a management school in Pune, the Tata Management Training Centre, which he hoped would become an Indian Administrative Service look-alike. And at a time when Tisco itself was hard-pressed for engineers, JRD willingly sent across some of his best men to the three new public sector steel complexes that came up in the sixties.

Meanwhile, G.D. Birla lured the world-famous MIT to India r help him establish Birla Institute of Technology and Science BITS), Pilani in the deserts of Rajasthan. He also funded hundreds of primary schools all over the country—in one year alone Birla opened 400 schools. Like Tata, Walchand too contributed towards his public sector rivals, training seamen for the two new shipping companies launched by Nehru. Walchand also bought a ship, the Dufferin, where Indians could train to become marine officers. And then when they couldn’t get jobs despite the right qualifications, he used his influence to force foreign shipping companies to hire Indians. In Ahmedabad, Lalbhai was the moving spirit behind the establishment of the Institute of Management and the Ahmedabad Education Society which later morphed into Gujarat University.

Apart from their patriotic entrepreneurship, their pioneering spirit and their promotion of education, these men are legends of their rare sense of economic nationalism. During the Raj they fought for the rights of Indian entrepreneurs to exist and vociferously criticized economic racism. Kasturbhai Lalbhai one of first Indian businessmen to be elected to Parliament (then known as the Central Legislative Assembly). G.D. Birla him there. Walchand Hirachand failed to get elected and J.R.D. Tata never tried, but both sent some of their best executives to the assembly. They stalled British lobbies not just own businesses but for Indian business interests in general. Birla fought for the Indian match industry as hard as Lalbhai fought for shipping. Tata men such as John Matthai and A.D. Shroff, Walchand men such as G.L. Mehta and S.N. Haji wrote significant portions of the legislation which governs corporate India today. And in August 1942, Kasturbhai Lalbhai helped engineer a strike in support of Mahatma Gandhi’s Quit India call, while Birla’s funding of Gandhi’s activities almost landed him in jail.

They are timeless examples of individuals unafraid to challenge the status quo and I felt that their experiences ought to be savoured by the next generation and the next. This book is about swadeshi role models for tomorrow’s legends.

Ironically, even as earlier I downplayed the feats of business leaders of the eighties and nineties such as Aditya Birla and Rahul Bajaj, it is because of them that this book was born. The release function of Business Maharajas, the prequel to Business Legends, was a panel discussion between Rama Prasad Goenka, Mukesh Ambani and Rahul Bajaj moderated by Titoo Ahiuwalia, India’s market research guru, in October 1996. During the event, Ahluwalia asked Goenka about the future of his group and its strategies. Goenka replied: ‘Even to look ten years ahead, we need a person with a dream and a vision. In the last few decades, India has had three dreamers in the corporate world: J.R.D. Tata, G.D. Birla and Dhirubhai Ambani. I am sorry to say that, in my eyes, there have been no other dreamers. If you don’t have a dreamer, you don’t have a visionary. I am a dreamer, not a visionary. That is my problem.’

It was this comment, dear reader, which became the inspiration for the book in yow hands.

| Introduction | xi | |

| GHANSHYAM DAS BIRLA | ||

| 1 | Birla Park, Calcutta, 1925 | 3 |

| 2 | The Rebel | 8 |

| 3 | Ghansyo | 19 |

| 4 | Crashing the Jute Barrier | 26 |

| 5 | From Business to Politics | 38 |

| 6 | Back in Business | 55 |

| 7 | Trade Talks | 66 |

| 8 | The Monkey Brigade | 79 |

| 9 | The Emissary | 93 |

| 10 | An Unidyllic Relationship | 106 |

| 11 | The Autumn Years | 124 |

| 12 | People, Partha and Profits | 137 |

| 13 | London, 11 June 1983 | 148 |

| WALCHAND HIRACHAND DOSHI | ||

| 1 | Delhi, 14 March 1923 | 15 |

| 2 | Mr Rightaway Now | 160 |

| 3 | Sholapur | 168 |

| 4 | The Phatak Years | 175 |

| 5 | SS Layalty | 185 |

| 6 | Who’s the Pirate? | 199 |

| 7 | ‘A Real Compliment’ | 211 |

| 8 | Big Daddy | 229 |

| 9 | War Babies | 243 |

| 10 | Looking for a Pal | 250 |

| 11 | Sumati Morarjee | 263 |

| 12 | The Firm | 270 |

| 13 | Gandhi, Nehru and All That | 278 |

| 14 | Siddhapur, 8 April 1953 | 289 |

| KASTURBHAI LALBHAI | ||

| 1 | Bombay, 8 August 1942 | 297 |

| 2 | The Builder | 301 |

| 3 | First Blood | 309 |

| 4 | The Economics of Nationalism | 325 |

| 5 | The Cotton Club | 336 |

| 6 | Khadi, Swadeshi and Boycott | 355 |

| 7 | Trade Wars | 365 |

| 8 | Heading West | 383 |

| 9 | An Incomparable Project | 394 |

| 10 | The Chetty Affair | 401 |

| 11 | Paterfamilias | 412 |

| 12 | Ahmedabad, 20 January 1980 | 421 |

| JEHANGIR RATAN DADABHOY TATA | ||

| 1 | Santa Cruz Airport, 1 August 1953 | 427 |

| 2 | Gentleman Jeh | 431 |

| 3 | The ‘Frenchy’ | 441 |

| 4 | Climb to the Top | 450 |

| 5 | India’s Numero Uno | 464 |

| 6 | Temples of Modern India | 481 |

| 7 | ‘As I Wake Up’ | 495 |

| 8 | Commonwealth | 507 |

| 9 | The Emperor Under Attack | 522 |

| 10 | Does Tata Mean Goodbye? | 539 |

| 11 | Striving for Perfection | 544 |

| 12 | Geneva, 29 November 1993 | 551 |

| Appendix I | 561 | |

| Appendix II | 563 | |

| Notes | 567 | |

| Chronology | 590 | |

| Select Bibliography | 603 | |

| Index | 634 | |

G.D. Birla, J.R.D. Tata, Walchand Hirachand and Kasturbhai Lalbhai-four pioneers who were a not afraid to think and plan big, at a time when Indian industry had to compete fiercely for market share against the multinational of the day. Together, they would lay the foundations for the golden age of Indian industry from 1951 to 1962. In this best-selling book, the closest look at these legends this far, Gita Piramal compellingly brings alive their ambition and achievement.

BUSINESS HISTORY HAS always fascinated me, so much so that I invested eight years for a doctorate in it. Unlike other freshly minted Ph. Ds, however, I never got round to publishing my research. This was partly because of my desire to use it to compile—some day in the nebulous future—an annotated bibliography on the economic history of Bombay. Such a project would be far more useful than my dissertation, I felt, yet the dissertation was the foundation for a ‘more useful’ book. I resolutely shelved years of hard labour waiting for the right moment to arrive.

The moment came unexpectedly and I was quick to seize it. While chatting with other business historians, I heard about the Lalbhais’ treasure trove of old letters. The entire collection of Kasturbhai Lalbhai’s correspondence had been carefully stored— and the family was willing to allow me to rifle through them. Thousands of letters which no one had ever seen! I felt as Aladdin must have as I unpacked the red cloth potlas into which the files were stuffed. Postcards from Mahatma Gandhi, the grey hand-made silk paper wedding invitation of Rajiv and Sonia Gandhi, angry exchanges between Kasturbhai Lalbhai and he income tax authorities, the arbitration papers dividing the brothers’ assets, a son’s sorrow over his mother’s illness—story came to life in front of my eyes. The added advantage was that my training and reading enabled me to grasp the contents of the letters, and to sift the trivial from the critical.

I am fascinated by people and their legacies, but that doesn’t explain why today’s manager should bother to read, about yesterday’s entrepreneurs. After all, business at the threshold of the millennium is quite different from what it was fifty years ago. The environment has changed, as have the products and the pace of response. With nothing in common, what possible lessons can there be in the lives of four long-gone businessmen to justify time spent reading these pages?

Quite a lot, actually. Because the similarity between India just before and after independence and India in the nineties is far greater than between India in the eighties and the nineties.

If this proposition seems rather extravagant, consider this:

During the pre- and post-independence period, several entrepreneurs outperformed the rest, producing products and services which were globally competitive. Four in particular— G.D. Birla, Walchand Hirachand Doshi, Kasturbhai Lalbhai and J.R.D. Tata—are particularly outstanding for their contribution to Indian industry.

In a 1939 listing of India’s biggest business houses—both local and foreign—the Tata Group topped the roll of honour with assets of Rs. 62.42 crores. The second largest, Martin Burn, was a poor second, with assets of a mere Rs. 18 crores. This was a formative age for the other three businessmen profiled here. The Birla group, at 13th place, owned assets of Rs. 4.85 crores, the Lalbhais had half that with Rs. 2.33 crores and ranked 30th. Walchand, in fact, was bigger than the Birlas at that point of time with assets of Rs. 3.66 crores in Scindia (ranked 17th but where he had three partners) and another Rs. 2.61 crores in his own group (25th).

By 1969 the picture had changed dramatically. The white burra sahebs had more or less abandoned their companies to Indians. According to the Report of the Industrial Licensing Policy Inquiry Committee, the Tata group remained India’s biggest business house with assets of Rs. 505.36 crores, but the Birlas had leapfrogged other groups to become the second largest in the country with assets of Rs. 456.40 crores. JRD and GD were running neck and neck despite the Tatas’ century-long advantage. This was a growth period for the Walchand group as well and they jumped to 9th rank with assets of Rs. 81.11 crores—and this didn’t take into account Scindia’s Rs. 55.99 crores as the group had parted ways with the shipping firm by then. Had they managed to retain control of the shipping giant, the Doshis would have hauled themselves to 4th place. At 18th place with Rs. 51.20 crores in assets, the Lalbhais hadn’t done too badly either.

What made these men special? G.D. Birla, with his modern mind, was a rare man who dared to challenge old traditions from a very young age, a thing unheard of in the conservative Marwari community. In the turbulent politics of the time, Birla liked to portray himself as an ambassador, mediating between Gandhi and the British, but his true contribution to India was industry. He and his three brothers built factories in the wilderness, factories which created wealth for local economies as well as the nation.

Most of G.D. Birla’s actions were carefully thought out and executed. He rarely acted on gut instinct. Walchand Hirachand, on the other hand, wanted to run before he could walk, carped his critics. He built an aircraft factory years before India could produce a diesel engine. He built a shipyard which the Nehru government considered too important to remain in private hands. If Bombay has drinking water, it is because of the huge pipelines he laid. When he became a building contractor, his father was convinced that Walchand would bankrupt the family. He took exceptional risks, but he built the foundations of modern India.

Waichand Hirachand’s main theatre of operations was Maharashtra. Another regional entrepreneur with a difference was Kasturbhai Lalbhai, who founded one of India’s largest textile dynasties. His skill as a negotiator first came to light when he crossed swords with Mahatma Gandhi. The year was 1917 and Kasturbhai was barely twenty-six. Despite his youth and the fact that his mill was then one of the smallest in Ahmedabad, his peers invited him to represent them in ending one of the most famous strikes in labour history.

While Lalbhai was carving a name for himself as a negotiator, T.R.D. Tata was busy writing his own chapter in the same book. Sick in bed, JRD drafted a labour manifesto for the huge steel works at Jamshedpur, a manifesto which ushered in new harmony into Tisco’s strike-torn history. Better known for his aviation feats and Air-India, little is known about Tata the businessman who shaped Tisco’s career for over half a century, which is why this book tries to look beyond Air-India to his other achievements. He surrounded himself with brilliant men, men who built companies such as Telco and Tata Chemicals. But did JRD realize his true potential?

In their drive to build huge empires, these men faced all kinds of challenges. From the way they tackled the obstacles facing them, today’s managers can learn how these savvy strategists warded off MNC attacks, extracted the best out of labour, and used the power of lobbying through associations to level the playing field.

In an era when data was hard to find, they had the answers. Given the paucity of trained professional economists on whom they could rely, they took to writing themselves on economic subjects. For decades, the Tata group’s pocket-size statistical handbook was the best source of general economic information. Few could argue against Walchand’s figures on shipping, construction and cement industries, or Kasturbhai’s knowledge of the textile industry. When men like GD, JRD, Walchahd and Kasturbhai spoke, people listened. They routinely published detailed reports which were then used by associations such as FICCI, the Indian Chamber of Commerce and the Indian Merchants’ Chamber.

But does that make them legends? What is the difference between a leader and a legend and what additional attributes does a leader need to qualify for ‘legendary’ status? Oddly enough, dictionary definitions are somewhat vague on the subject, though most of them agree that technically a legend is a story or collection of stories of a saint’s life. I doubt if the four businessmen featured here are perfect, but I do consider them legends. Why? Legends become legends not because of their personal triumphs but for the impact their work and effort have on hundreds of other lives. A trader thinks of today’s profit, an industrialist looks at tomorrow’s balance sheet, but a legend thinks of the next generation.

Indian corporate lore is full of awesome stories of remarkable businessmen who have established powerful dynasties. There are marvellous rags-to-riches stories such as that of M.S. Oberoi (b 1900) who made a mark for himself hoteliering, or of Mafatlal Gagalbhai (1873—1944), the Bombay textile tycoon who started his business career selling cut-pieces on street pavements. There are hundreds of inspiring stories like that of H.P. Nanda (b 1917), the doughty refugee from Pakistan who built Escorts and then fought off a messy takeover bid for the tractors-to-motorcycles company; or that of Laxmanrao Kirloskar (1869— 1956), who lovingly encouraged roses to flower among cacti while building the group’s engineering companies. There are stories of nationalist-businessmen like Jamnalal Bajaj (1889— 1942); of fine technocrats like Ardeshir Godrej (1868—1936) the locksmith; and of customer-focused service-providers like T.V Sundaram Iyengar who went on to promote the TVS group. Each of these offers fascinating insights about how to make money. But legends have to have a vision beyond the accumulation of personal wealth.

I selected G.D. Birla, Walchand Hirachand Doshi, Kasturbhai Lalbhai and J.R.D. Tata for this book because I felt their entrepreneurship styles were a cut above the rest. To understand fully their contribution to Indian industry, we have to assess them in the context of their times.

India was a jewel in the British crown, but most Indians were too poor to afford shoes. Even JRD’s father went barefoot for the first fifteen years of his life. We’ve forgotten the famines, the riots and the plagues which India suffered. When the British left, they proudly boasted that they had built the world’s tenth most industralized nation. But we were a colonial economy and it was heavily skewed in favour of the export of agricultural goods and raw materials, and the import of finished goods. India made very few products—almost everything for the past century and more had been imported. At this time there were thousands of Indian businessmen who used the shortages for private gain and profit. But not these men.

Admittedly, this view is contrary to public perception, which regards most businessmen, particularly G.D. Birla, as monopolists. But there is sufficient evidence to show that this was not the case. In fact, the four men profiled here went out of their way to encourage entrepreneurs to start new businesses. As G.D. Birla once said, ‘Any fool can establish a business when there is a boom. But it is during a period of depression that one’s ability to establish and run a business is really tested. I therefore appeal to businessmen not to be disheartened but to learn to take risks.’* This was not mere rhetoric. When small businesses ran aground, these four men did their best to help.

G.D. Birla encouraged other Indian businessmen to enter the jute business along with him. Walchand Hirachand bailed out small Indian shippers wherever and whenever he could. Kasturbhai Lalbhai helped other millowners in Ahmedabad to improve the performance of their cotton mills and the quality of the cloth they produced. In Jamshedpur, J.RD. Tata developed satellite empires around Tisco. They fostered a community spirit even though it meant creating new rivals and more competition for themselves. It was only after the government grew antagonistic to big business did the atmosphere get vitiated in the seventies and eighties.

This is one reason why I refer to these four men as legends. There are three more.

Business legends don’t take the easy road to prosperity Birla, Walchand, Lalbhai and Tata hacked roads through jungles, built factories in villages, transformed barren tracts of land into profitable assets, and inculcated the industrial ethos into the mindset of peasants. They built large industrial complexes which were as ambitious at the time as Ambani’s Jamnagar refinery is today. G.D. Birla’s aluminium smelter at Renukoot, Kasturbhai Lalbhai’s Atul chemical complex, J.R.D. Tata’s Telco plant at Pune and the extensions at Tata Steel, Walchand Hirachand’s shipyard at Visakhapatnam and the Premier Auto plant outside Bombay are testimony to their grit and vision. In most cases, they pioneered the industries in which they operated.

Nor did they boast about their victories (with the exception of Walchand Hirachand perhaps!). As JRD once modestly put it, ‘I am a businessman. I was born in business. I was born in industry. I was trained in it, and I believe that the future of this country lies in economic development. Therefore my primary role is that of a businessman. I’m not boasting about it and I don’t deserve credit for it.’ Nonetheless, the companies they established, the complexes they constructed are the foundation on which the economy rests today. Few factories on such scales came up in the seventies and eighties. In short, these are the men who built Nehru’s temples of modern India.

A third reason for bestowing legendary status on these four men is because of their commitment to education. All four invested heavily in the tools for progress: schools and colleges whose alumni serviced the ‘temples’ both in the private and public sector. JRD founded several premier institutions such as the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, the Tata Institute of Social Sciences and even a management school in Pune, the Tata Management Training Centre, which he hoped would become an Indian Administrative Service look-alike. And at a time when Tisco itself was hard-pressed for engineers, JRD willingly sent across some of his best men to the three new public sector steel complexes that came up in the sixties.

Meanwhile, G.D. Birla lured the world-famous MIT to India r help him establish Birla Institute of Technology and Science BITS), Pilani in the deserts of Rajasthan. He also funded hundreds of primary schools all over the country—in one year alone Birla opened 400 schools. Like Tata, Walchand too contributed towards his public sector rivals, training seamen for the two new shipping companies launched by Nehru. Walchand also bought a ship, the Dufferin, where Indians could train to become marine officers. And then when they couldn’t get jobs despite the right qualifications, he used his influence to force foreign shipping companies to hire Indians. In Ahmedabad, Lalbhai was the moving spirit behind the establishment of the Institute of Management and the Ahmedabad Education Society which later morphed into Gujarat University.

Apart from their patriotic entrepreneurship, their pioneering spirit and their promotion of education, these men are legends of their rare sense of economic nationalism. During the Raj they fought for the rights of Indian entrepreneurs to exist and vociferously criticized economic racism. Kasturbhai Lalbhai one of first Indian businessmen to be elected to Parliament (then known as the Central Legislative Assembly). G.D. Birla him there. Walchand Hirachand failed to get elected and J.R.D. Tata never tried, but both sent some of their best executives to the assembly. They stalled British lobbies not just own businesses but for Indian business interests in general. Birla fought for the Indian match industry as hard as Lalbhai fought for shipping. Tata men such as John Matthai and A.D. Shroff, Walchand men such as G.L. Mehta and S.N. Haji wrote significant portions of the legislation which governs corporate India today. And in August 1942, Kasturbhai Lalbhai helped engineer a strike in support of Mahatma Gandhi’s Quit India call, while Birla’s funding of Gandhi’s activities almost landed him in jail.

They are timeless examples of individuals unafraid to challenge the status quo and I felt that their experiences ought to be savoured by the next generation and the next. This book is about swadeshi role models for tomorrow’s legends.

Ironically, even as earlier I downplayed the feats of business leaders of the eighties and nineties such as Aditya Birla and Rahul Bajaj, it is because of them that this book was born. The release function of Business Maharajas, the prequel to Business Legends, was a panel discussion between Rama Prasad Goenka, Mukesh Ambani and Rahul Bajaj moderated by Titoo Ahiuwalia, India’s market research guru, in October 1996. During the event, Ahluwalia asked Goenka about the future of his group and its strategies. Goenka replied: ‘Even to look ten years ahead, we need a person with a dream and a vision. In the last few decades, India has had three dreamers in the corporate world: J.R.D. Tata, G.D. Birla and Dhirubhai Ambani. I am sorry to say that, in my eyes, there have been no other dreamers. If you don’t have a dreamer, you don’t have a visionary. I am a dreamer, not a visionary. That is my problem.’

It was this comment, dear reader, which became the inspiration for the book in yow hands.

| Introduction | xi | |

| GHANSHYAM DAS BIRLA | ||

| 1 | Birla Park, Calcutta, 1925 | 3 |

| 2 | The Rebel | 8 |

| 3 | Ghansyo | 19 |

| 4 | Crashing the Jute Barrier | 26 |

| 5 | From Business to Politics | 38 |

| 6 | Back in Business | 55 |

| 7 | Trade Talks | 66 |

| 8 | The Monkey Brigade | 79 |

| 9 | The Emissary | 93 |

| 10 | An Unidyllic Relationship | 106 |

| 11 | The Autumn Years | 124 |

| 12 | People, Partha and Profits | 137 |

| 13 | London, 11 June 1983 | 148 |

| WALCHAND HIRACHAND DOSHI | ||

| 1 | Delhi, 14 March 1923 | 15 |

| 2 | Mr Rightaway Now | 160 |

| 3 | Sholapur | 168 |

| 4 | The Phatak Years | 175 |

| 5 | SS Layalty | 185 |

| 6 | Who’s the Pirate? | 199 |

| 7 | ‘A Real Compliment’ | 211 |

| 8 | Big Daddy | 229 |

| 9 | War Babies | 243 |

| 10 | Looking for a Pal | 250 |

| 11 | Sumati Morarjee | 263 |

| 12 | The Firm | 270 |

| 13 | Gandhi, Nehru and All That | 278 |

| 14 | Siddhapur, 8 April 1953 | 289 |

| KASTURBHAI LALBHAI | ||

| 1 | Bombay, 8 August 1942 | 297 |

| 2 | The Builder | 301 |

| 3 | First Blood | 309 |

| 4 | The Economics of Nationalism | 325 |

| 5 | The Cotton Club | 336 |

| 6 | Khadi, Swadeshi and Boycott | 355 |

| 7 | Trade Wars | 365 |

| 8 | Heading West | 383 |

| 9 | An Incomparable Project | 394 |

| 10 | The Chetty Affair | 401 |

| 11 | Paterfamilias | 412 |

| 12 | Ahmedabad, 20 January 1980 | 421 |

| JEHANGIR RATAN DADABHOY TATA | ||

| 1 | Santa Cruz Airport, 1 August 1953 | 427 |

| 2 | Gentleman Jeh | 431 |

| 3 | The ‘Frenchy’ | 441 |

| 4 | Climb to the Top | 450 |

| 5 | India’s Numero Uno | 464 |

| 6 | Temples of Modern India | 481 |

| 7 | ‘As I Wake Up’ | 495 |

| 8 | Commonwealth | 507 |

| 9 | The Emperor Under Attack | 522 |

| 10 | Does Tata Mean Goodbye? | 539 |

| 11 | Striving for Perfection | 544 |

| 12 | Geneva, 29 November 1993 | 551 |

| Appendix I | 561 | |

| Appendix II | 563 | |

| Notes | 567 | |

| Chronology | 590 | |

| Select Bibliography | 603 | |

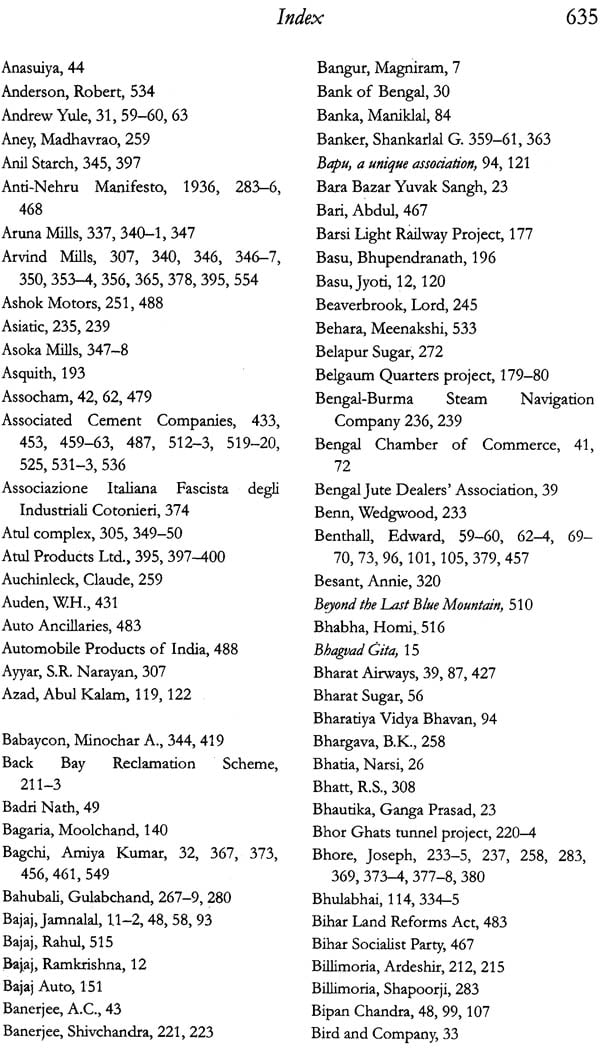

| Index | 634 | |