Wine of the Mystic - The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam A spiritual Interpretation

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAO956 |

| Author: | Paramhansa Yogananda |

| Publisher: | Yogoda Satsanga Society of India |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2017 |

| ISBN: | 9789383203680 |

| Pages: | 255 (24 Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 10.0 inch x 7.5 inch |

| Weight | 1 kg |

Book Description

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam as translated by Edward FitzGerald has long been one of the most beloved, and least understood, poems in the English language: In an illuminating new interpretation, Paramahansa Yogananda— renowned for his Autobiography of a Yogi and widely revered as one of India's great modern-day saints—reveals the mystical essence of this enigmatic masterpiece, bringing to light the deeper truth and beauty behind its veil of metaphor.

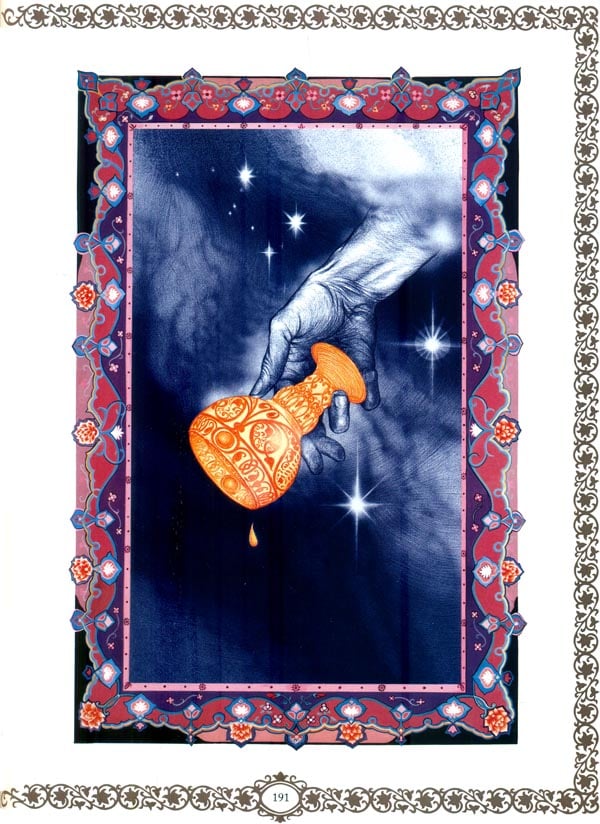

Commonly thought to be a celebration of wine and other earthly pleasures, these lyrical Persian quatrains find their true voice when read as a hymn to the transcendent joys of Spirit.

This illustrated edition of Wine of the Mystic introduces for the first time in book form Paramahansa Yogananda's complete commentaries on an enduring treasure of world literature.

Long ago in India I met a hoary Persian poet who told me that the poetry of Persia often has two meanings, one inner and one outer. I remember the great satisfaction I derived from his explanations of the twofold significance of several Persian poems.

One day as I was deeply concentrated on the pages of Omar Khayyam's Rubaiyat, I suddenly beheld the walls of its outer meanings crumble away, and the vast inner fortress of golden spiritual treasures stood open to my gaze.

Ever since, I have admired the beauty of the previously invisible castle of inner wisdom in the Rubaiyat. I have felt that this dream-castle of truth, which can be seen by any penetrating eye, would be a haven for many shelter-seeking souls invaded by enemy armies of ignorance.

Profound spiritual treatises by some mysterious divine law do not disappear from the earth even after centuries of misunderstanding, as in the case of the Rubaiyat. Not even in Persia is all of Omar Khayyam's deep philosophy understood in its entirety, as I have tried to present it.

Because of the hidden spiritual foundation of the Rubaiyat it has withstood the ravages of time and the misinterpretations of many translators, remaining a perpetual mansion of wisdom for truth-loving and solace-seeking souls.

In Persia Omar Khayyam has always been considered a highly advanced mystical teacher, and his Rubaiyat revered as an inspired Sufi scripture.* "The first great Sufi writer was Omar Khayyam," writes Professor Charles F. Horne in the Introduction to the Rubaiyat, which appears in Vol. VIII of "The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East" series (Parke, Austin & Lipscomb, London, 1917). "Unfortunately, Omar, by a very large number of Western readers, has come to be regarded as a rather erotic pagan poet, a drunkard interested only in wine and earthly pleasure. This is typical of the confusion that exists on the entire subject of Sufism. The West has insisted on judging Omar from its own viewpoint. But if we are to understand the East at all, we must try to see how its own people look upon its writings. It comes as a surprise to many Westerners when they are told that in Persia itself there is no dispute whatever about Omar's verses and their meaning. He is accepted quite simply as a great religious poet.

"What then becomes of all his passionate praise of wine and love? These are merely the thoroughly established metaphors of Sufism; the wine is the joy of the spirit, and the love is the rapturous devotion to God....

"Omar rather veiled than displayed his knowledge. That such a man would be regarded by the Western world as an idle reveller is absurd. Such wisdom united to such shallowness is self-contradictory."

Omar and other Sufi poets used popular similes and pictured the ordinary joys of life so that the worldly man could compare those ordinary joys of mundane life with the superior joys of the spiritual life. To the man who habitually drinks wine to temporarily forget the sorrows and unbearable trials of his life, Omar offers a more delightful nectar of enlightenment and divine ecstasy which has the power, when used by man, to obliterate his woes for all time. Surely Omar did not go through the labour of writing so many exquisite verses merely to tell people to escape sorrow by drugging their senses with wine!

J. B. Nicolas, whose French translation of 464 rubaiyat (quatrains) appeared in 1867, a few years after Edward FitzGerald's first edition, opposed FitzGerald's views that Omar was a materialist. FitzGerald refers to this fact in the introduction to his own second edition, as follows :

"M. Nicolas, whose edition has reminded me of several things, and instructed me in others, does not consider Omar to be the material epicurian that I have literally taken him for, but a mystic, shadowing the Deity under the figure of wine, wine-bearer, etc., as Hafiz is supposed to do; in short, a Sufi poet like Hafiz and the rest....As there is some traditional presumption, and certainly the opinion of some learned men, in favour of Omar's being a Sufi—even something of a saint—those who please may so interpret his wine and cup-bearer."

Omar distinctly states that wine symbolizes the intoxication of divine love and joy. Many of his stanzas are so purely spiritual that hardly any material meanings can be drawn from them, as for instance in quatrains XLIV, LX, and LXVI.

With the help of a Persian scholar, I translated the original Rubaiyat into English. But I found that, though literally translated, they lacked the fiery spirit of Khayyam's original. After I compared that translation with FitzGerald's, I realized that FitzGerald had been divinely inspired to catch exactly in gloriously musical English words the soul of Omar's writings.

Therefore I decided to interpret the inner hidden meaning of Omar's verses from FitzGerald's translation rather than from my own or any other that I had read.*

In order to grasp readily the logic and depth of the "Spiritual Interpretations," I hope every reader will read those offerings along with the Glossary. In the "Practical Application" sections, readers who feel so inclined will find many sincere and useful suggestions as to how these truths may be beneficially applied to daily life.

Since Omar's real dream-wine was the joyously intoxicating wine of divine love, I have written, in the Addenda, a few paragraphs on Divine Love, which I received in the sacred temple of my inner perceptions. This Divine Love is what Omar advises as a panacea for all human woes and questionings.

As I worked on the spiritual interpretation of the Rubaiyat, it took me into an endless labyrinth of truth, until I was rapturously lost in wonderment. The veiling of Khayyam's metaphysical and practical philosophy in these verses reminds me of "The Revelation of St. John the Divine." The Rubaiyat may rightly be called "The Revelation of Omar Khayyam."

This volume, presenting Paramahansa Yogananda's complete commentaries on the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, brings together the poetic and spiritual insights of three men of great renown, whose lives spanned a period of more than nine hundred years. The eleventh-century verses of Omar Khayyam, and their nineteenth-century translation by Edward FitzGerald, have long delighted readers. Yet the true meaning of the poem has been a subject of much debate. In his illuminating interpretation, Paramahansa Yogananda reveals —behind the enigmatic veil of metaphor— the mystical essence of this literary classic.

Acclaimed for his Autobiography of a Yogi and other writings, Paramahansa Yogananda is widely revered as one of India's great modern-day saints. His interpretation of the Rubaiyat was one aspect of a lifelong effort to awaken people of both East and West to a deeper awareness of the innate divinity latent in every human being. Like the enlightened sages of all spiritual traditions, Sri Yogananda perceived that underlying the doctrines and practices of the various religions is one Truth, one transcendent Reality. It was this universal outlook and breadth of vision that enabled him to elucidate the profound kinship between the teachings of India's ancient science of Yoga and the writings of one of the greatest and most misunderstood mystical poets of the Islamic world, Omar Khayyam.

The Mystery of Omar Khayyam

In the history of world literature, Omar Khayyam is an enigma. Surely no other poet of any epoch has achieved such extraordinary fame through such a colossal misreading of his work. Beloved today the world over, Khayyam's poetry would very likely still be moldering unknown in the archives of antiquity were it not for the beautiful translations of his Rubaiyat by the English writer Edward FitzGerald. The paradox is that FitzGerald misinterpreted both the character and the intent of the Persian poet on whose work he bestowed immortality.

FitzGerald included in his editions of the Rubaiyat a biographical sketch called "Omar Khayyam: The Astronomer-Poet of Persia," in which he sets forth his conviction that Khayyam was an anti-religious materialist who believed that life's only meaning was to be found in wine, song, and worldly pleasures:

Having failed (however mistakenly) of finding any Providence but Destiny, and any world but this, he set about making the most of it; preferring rather to soothe the soul through the senses into acquiescence with things as he saw them, than to perplex it with vain disquietude after what they might be....He takes a humorous or perverse pleasure in exalting the gratification of sense above that of intellect, in which he must have taken great delight, although it failed to answer the questions in which he, in common with all men, was most vitally interested....He is said to have been especially hated and dreaded by the Sufis, whose practice he ridiculed.

A more historically accurate portrait emerges from the research of modern-day scholars of both East and West, who have established that far from ridiculing the Sufis, Omar probably counted himself among their number. In 1941, Swami Govinda Tirtha published one of the most detailed studies of Omar Khayyam's life and writings ever made, based on a comprehensive survey of most (if not all) of the existing material on Khayyam—including biographical data from the time of Omar himself. From that and other works of scholarship are summarized the following historical facts.

Omar's full name was Ghiyath ud Din Abu'l Fatah Omar bin Ibrahim al Khayyam. (Khayyam means tentmaker, referring it seems to the trade of his father Ibrahim. Omar took this name as his takhallus, or pen name.) He was born at Naishapur in the province of Khorastan (located in the northeastern part of present-day Iran) on May 18, 1048.t His keen intelligence and strong memory, we are told, enabled him to become adept in the academic subjects of his day by the age of seventeen. Owing to the early death of his father, Omar began searching for a means of supporting himself, and thus embarked on an illustrious public career when he was only eighteen.

A tract he wrote on algebra won him the patronage of a rich and influential doctor in Samarkand. Later he obtained a position at the court of Sultan Malik Shah, which included serving as the ruler's personal physician. By his mid-twenties, Khayyam had become the head of an astronomical observatory and had authored additional treatises on mathematics and physics. He played a leading role in the reformation of the Persian calendar—devising a new calendar that was even more accurate than the Gregorian, which came into use in Europe five hundred years later. Summing up Khayyam's professional achievements, Swami Govinda Tirtha tells us that Omar "was reckoned in his time second to Avicenna in sciences.§ But he combined in himself other qualifications"—having become proficient in studies of the Koran, in history and languages, astrology, mechanics, and clay modeling. (His interest in the latter pursuit is reflected in the several quatrains where he uses clay pottery and pottery-making to refer metaphorically to spiritual truths.)

After the death of Sultan Malik Shah in 1092, Omar lost his place at court and subsequently made a pilgrimage to Mecca. He then returned to Naishapur, where he apparently lived as a recluse. About the remaining decades of his life, only scanty information has survived; in particular, "over the [last] sixteen years of his life there is drawn an impenetrable veil."* Some scholars say he spent the second half of his life pursuing the spiritual disciplines of the Sufis, and in writing the mystical poems that have survived as the Rubaiyat. Whether or not this is true, it is known that during this period he authored a treatise on metaphysics entitled Julliat-i-Wajud or Roudat ul Qulub, which clearly reveals his views on Sufi mysticism. Swami Govinda Tirtha, whose research indicates that this work may have been written around 1095, quotes from its conclusion as follows:

The seekers after cognition of God fall into four groups :

First : The Mutakallamis who prefer to remain content with traditional belief and such reasons and arguments as are consistent therewith.

Second : Philosophers and Hakims who seek to find God by reasons and arguments and do not rely on any dogmas. But these men find that their reasons and arguments ultimately fail and succumb.

Third: Isma’ilis and Ta’limis who say that the knowledge of God is not correct unless it is acquired through the right source, because there are various phases in the path for the cognition of the Creator, His Being and Attributes, where arguments fail and minds are perplexed. Hence it is first necessary to seek the Word from the right source.

Fourth: The Sufis who seek the knowledge of God not merely by contemplation and meditation [on the scriptures], but by purification of the heart and cleansing the faculty of perception from its natural impurities and engrossment with the body. When the human soul is thus purified it becomes capable of reflecting the Divine Image. And there is no doubt that this path is the best, because we know that the Lord does not withhold any perfection from [the] human soul. It is the darkness and impurity which is the main obstacle—if there be any. When this veil disappears and the obstructions are removed, the real facts will be evident as they are. And our Prophet (may peace be on him) has hinted to the same effect.

What is remarkable about this passage is not just that it unequivocally confirms Omar's Sufi sympathies, but that it expresses his spiritual goals in terms that are almost identical to those of India's ancient science of Yoga.

| Introduction | ix | |

| Foreword | xiii | |

| Quatrain | ||

| 1 | "Awake! for Morning in the Bowl of Night" | 3 |

| 2 | "Dreaming when Dawn's Left Hand was in the Sky" | 7 |

| 3 | "And, as the Cock crew, those who stood before" | 8 |

| 4 | "Now the New Year reviving old Desires" | 10 |

| 5 | "Iram indeed is gone with all its Rose" | 13 |

| 6 | "And David's Lips are lock't; but in divine" | 17 |

| 7 | "Come, fill the Cup, and in the Fire of Spring" | 21 |

| 8 | "And look -a thousand Blossoms with the Day" | 22 |

| 9 | "But come with old Khayyam, and leave the Lot" | 25 |

| 10 | "With me along some Strip of Herbage strown" | 27 |

| 11 | "Here with a Loaf of Bread beneath the Bough" | 31 |

| 12 | "Wow sweet is mortal Sovranty!'-think some" | 33 |

| 13 | "Look to the Rose that blows about us -'Lo" | 35 |

| 14 | "The Worldly Hope men set their Hearts upon" | 36 |

| 15 | "And those who husbanded the Golden Grain" | 41 |

| 16 | "Think, in this batter'd Caravanserai" | 43 |

| 17 | "They say the Lion and the Lizard' keep" | 44 |

| 18 | "I sometimes think that never blows so red" | 49 |

| 19 | "And this delightful Herb whose tender Green" | 51 |

| 20 | "Ah, my Beloved, fill the Cup that clears" | 55 |

| 21 | "Lo! some we loved, the loveliest and the best" | 56 |

| 22 | "And we, that now make merry in the Room" | 58 |

| 23 | "Ah, make the most of what we yet may spend" | 63 |

| 24 | "Alike for those who for Today prepare" | 64 |

| 25 | "Why, all the Saints and Sages who discuss'd" | 69 |

| 26 | "Oh, come with old Khayyam, and leave the Wise" | 70 |

| 27 | "Myself when young did eagerly frequent" | 75 |

| 28 | "With them the Seed of Wisdom did I sow" | 76 |

| 29 | "Into this Universe, and why not knowing" | 81 |

| 30 | "What, without asking, hither hurried whence?" | 82 |

| 31 | "Up from Earth's Centre through the Seventh Gate" | 84 |

| 32 | "There was a Door to which I found no Key" | 90 |

| 33 | "Then to the rolling Heav'n itself I cried" | 95 |

| 34 | "Then to this earthen Bowl did I adjourn" | 97 |

| 35 | "I think the Vessel, that with fugitive" | 101 |

| 36 | "For in the Market-place, one Dusk of Day" | 105 |

| 37 | "Ah, fill the Cup:-what boots it to repeat" | 107 |

| 38 | "One Moment in Annihilation's Waste" | 108 |

| 39 | "How long, how long, in Infinite Pursuit" | 111 |

| 40 | "You know, my Friends, how long since in my House" | 115 |

| 41 | "For 'Is' and 'Is-NOT' though with Rule and Line" | 116 |

| 42 | "And lately, by the Tavern Door agape" | 119 |

| 43 | "The Grape that can with Logic absolute" | 120 |

| 44 | "The mighty Mahmud, the victorious Lord" | 123 |

| 45 | "But leave the Wise to wrangle, and with me" | 124 |

| 46 | "For in and out, above, about, below" | 127 |

| 47 | "And if the Wine you drink, the Lip you press" | 129 |

| 48 | "While the Rose blows along the River Brink" | 130 |

| 49 | "'Tis all a Chequer-board of Nights and Days" | 135 |

| 50 | "The Ball no Question makes of Ayes and Noes" | 138 |

| 51 | "The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ" | 141 |

| 52 | "And that inverted Bowl we call The Sky" | 142 |

| 53 | "With Earth's first Clay They did the Last Man's knead" | 144 |

| 54 | "I tell Thee this starting from the Goal" | 146 |

| 55 | "The Vine had struck a Fibre; which about" | 149 |

| 56 | "And this I know: whether the one True Light" | 153 |

| 57 | "Oh, Thou, who didst with Pitfall and with Gin" | 154 |

| 58 | "Oh, Thou, who Man of baser Earth didst make" | 156 |

| 59 | "Listen again. One evening at the Close" | 157 |

| 60 | "And, strange to tell, among the Earthen Lot" | 158 |

| 61 | "Then said another -`Surely not in vain" | 161 |

| 62 | "Another said -'Why, ne'er a peevish Boy" | 163 |

| 63 | "None answer'd this; but after Silence spake" | 164 |

| 64 | "Said one - `Folks of a surly Tapster tell" | 166 |

| 65 | "Then said another with a long-drawn Sigh" | 169 |

| 66 | "So while the Vessels one by one were speaking" | 171 |

| 67 | "Ah, with the Grape my fading Life provide" | 172 |

| 68 | "That ev'n my buried Ashes such a Snare" | 175 |

| 69 | "Indeed the Idols I have loved so long" | 176 |

| 70 | "Indeed, indeed, Repentance oft before" | 179 |

| 71 | "And much as Wine has play'd the Infidel" | 180 |

| 72 | "Alas, that Spring should vanish with the Rose!" | 183 |

| 73 | "Ah, Love! could thou and I with Fate conspire" | 184 |

| 74 | "Ah, Moon of my Delight, who know'st no wane" | 189 |

| 75 | "And when Thyself with shining Foot shall pass" | 190 |

| Addenda | ||

| "Omar's Dream-Wine of Love," by Paramahansa Yogananda | 196 | |

| The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (consecutive quatrains 1-75) | 199 | |

| About the Author | 221 | |

| Paramahansa Yogananda: A Yogi in Life and Death | 225 | |

| Aims and Ideals of Yogoda Satsanga Society of India | 226 |