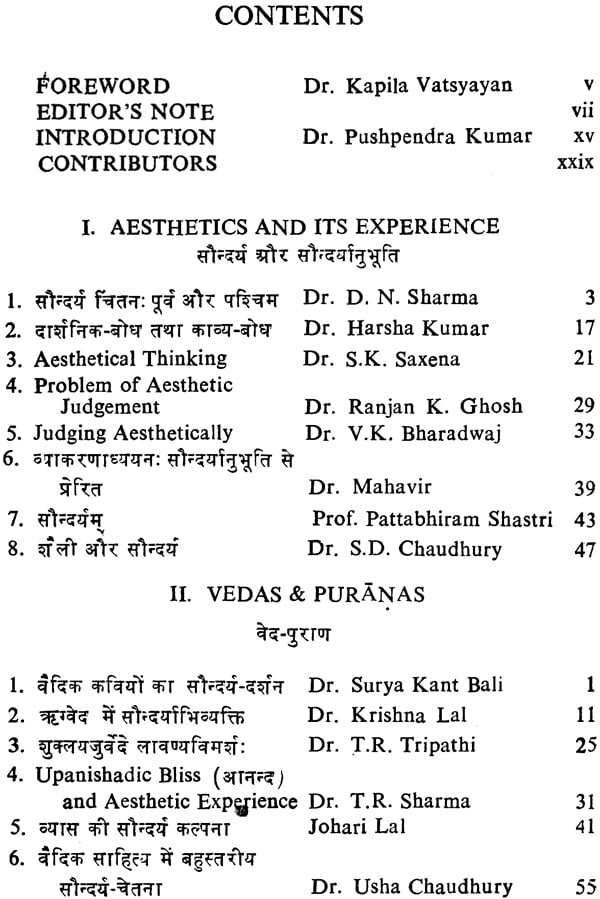

संस्कृत साहित्य और सौन्दर्यचेतना: Aesthetics and Sanskrit Literature

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NZH061 |

| Author: | Dr. Pushpendra Kumar |

| Publisher: | Nag Publisher |

| Language: | English and Hindi |

| Edition: | 1980 |

| Pages: | 390 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.0 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 480 gm |

Book Description

It has been contended that less has been said about aesthetics and specially Indian aesthetics than any other subject. To make any headway in aesthetics two qualities are required which rarely go together-(i) artistic sensitivity and (ii) hard, patient logical thinking. Those who are artistically sensitive do not bother their heads to analyse their experiences and discriminate the factors involved in appreciation. On the other hand, those who are capable of patient and logical thought generally lack taste. These theories might explain the facts but they are the wrong facts, that is why the progress in the field of aesthetics is said to be slow.

In the last fifty years or so when there has been a renewed interest in aesthetics, persons of tastes and logical thinking have concerned themselves with the subject. While they have produced some novel theories of aesthetics, but without much advancement in the field, as each one of them has given us just another theory of aesthetics as a whole. These theories might be all very good but frequently they throw little light on the specific problems which confront the critics or anyone else, who wishes to understand and appreciate the works of art. The trouble is that we have not seriously thought of formulating the fundamental questions and their solutions in the field of aesthetics.

Aesthetics may be thought in variety of ways. The historical approach consists of a chronological survey of what has been said about the nature of art, beauty, aesthetic experience etc. by the thinkers of the past. The result is rarely more than information. ‘Plato said this and Hagel said that’. The importance of such information is not to be under-estimated, but the person who has it, is not an aesthetician and to impart it, is not to teach him aesthetics.

The comparative approach is akin to the historical approach. It presents conflicting answers to each of the questions pertaining to aesthetics. The advantage of this method is that it makes the students aware of the diversity of answers given by the intelligent and sophisticated thinkers to the same questions. But the usual result is again information about-who said, what, and why and how his vies differ from someone else. The importance of this sort of information is also not to be underrated, but unless the person becomes actively engaged in reasoning through the conflicts presented to him, he will learn little philosophy of aesthetics.

A third approach called systematic, is the presentation of a reasoned set of answers to the questions of aesthetics. This can be an effective way of teaching aesthetics but it tends to be doctrinaire and presents the problems, generally, in a dreary style. This type of approach helps the students to have a clear view of important problems in aesthetics and to engage their minds in thinking them through. The best means to this is to give good illustrations.

Many claims have been made or aesthetics; that it will improve art by enlightening artists, that it will clarify criticism or raise its standard and put it on a solid foundation, that it will lead to a fuller and deeper appreciation of art, literature and so on, but no evidence is there to support it. The best answer would be that the problems of aesthetics are inherently intriguing and the persuit of them is intellectually worthwhile.

‘What is art’, around which much of aesthetical thinking has centred. It can be answered either by a scrutiny of art itself or by looking up the definition of art. The concept of art, in aesthetics, the concept of beauty and goodness, truth and fiction, expression and emotion, form and content is the philosophical question, typically conceptual in nature. These questions can be, if at all, settled by argument and thus aesthetics can be learnt, philosophically, only be active engagement in reasoning.

Aesthetics is not an independent system of Indian thinking but it assures summum bonum. Principles of Indian aesthetics are not strictly limited to a particular disciple or a system. They are strewn profusely all over the Indic studies; Vedic, classic, historic and modern. It is, on the other hand, an independent system in the west. Almost all the modern works on aesthetics in India are, more or less, impregnated more with western concepts than true Indian ones. Even some Indian scholars of the day are, yet biased to believe, if a work on Indian aesthetics is really possible. But there is a fundamental difference between Indian aesthetics and other systems of thought. The former is super natural, divine and supersensuous to some extant. This may not be justified, always by logical propositions. The later is natural, mundane and justifiable by logical maxims. In a word, one is the kingdom of heart and the other is the realm of the head.

All the dormant feelings of the aesthetic experience are virtually impersonal, though they appear otherwise. Love relished aesthetically does not stimulate sex. Laughter cuts joke with nobody, pathos result in no pain, anger provokes none to hit and wonders strike no astonishment, but every feeling matures there in pure and impersonal happiness.

The aim of other philosophies, in India, is to get rid of pain and suffering and to flee away from the bondage of the world, but aesthetics is to convert the pain and suffering into pleasure and peace; the poison into nectar and the mundane life into a divine one. Elements of Indian aesthetics are, therefore, neither preserved in the dry canonical injunctions, nor in the contradictory philosophical speculations. They find their roots deep down in the mystic-estoric concept and unveil the secret that how one’s own soul could look back at the Paramount Soul. To an aesthete wind of the earth breaths honey, rivers stream in honey, everything taste honey. In an ecstacy of joy, he bursts out-everything here, sweet, sweet, sweet.

Some have a complaint that there is not really an independent stream called aesthetics, in Indian philosophy. That is not true as all the major thoughts and concepts of Indian aesthetics are found deliberated in one or other system of Indian philosophy. The word aesthetic gives us the meaning of ‘perception’ or ‘feeling’. To feel or to perceive, more or less, is the common characteristic of all Indian philosophies. If Indian philosophers assimilate the aesthetic concepts in such a philosophical system which deals with thoughts and concepts of ‘cognition’ and ‘feeling’-it would not be less than an independent stream of aesthetics.

The Rasa-school of Vaisnavas, appreciating Sri Krsna as to be the symbolic God, has stretched the true characteristic of Indian aesthetics. Originality, lucidity, taste and rich scientific value of it has been tasted many a times on the touchstone of Indian psychology and spiritualism. The concept of ‘lumionsity’ preached by the Kashmir Saivism, the doctrine of beauty and bliss advocated by the Saktas and the self conscious happiness of Bengal Vaisnavism- made a three-streamed confluence of Indian aesthetics. Indian aesthetics, virtually, delivers the message of the immortal abode of bliss and happiness. The Supreme God (Nandanandana) enjoys supreme bliss of love-in union with his eternal consort along with eight blissful playmates, known mythically as Sakhis and aesthetically eight supersensuous relishes. (Asta-rasa).

India Acaryas have said that sarvam rasamayam jagat. That is the whole universe is sweetend by relish, in other words, they have indentified rasa with Brahman (sarvam brahma-mayam jagat). Sankaracarya, though a devout Vedantin is practically a devotee of the goddess of beauty, bliss and energy. The worship of Sriyantra suggests the supersensuous union of the Supreme God with the most exalted beauty in an all blissful happy state. The Vaisnavas also think in the same way and the only difference is that the Vedantins and Saktas believe in the concept of one-in-two and Vaisnavas believe in the concept of two-in-one. Both these concepts have a basis in the blissful experience i.e. an aroma of aesthetics.

There are three main streams of Indian aesthetics, (i) the stream of literature and poetics, (ii) the stream of drama and dramaturgy and (iii) the stream of fine art and culture. There is also fourth stream of aesthetics i.e. divine aesthetics inculcated by the Tantras and Vaisnava literature. Acarya Abhinavagupta- the celebrated aesthete, holds that the poetry and the drama both are identical as far as the aesthetic experience is concerned. In the field of dramatic relish, the elements of aesthetic happiness come to the state of realization through the process of perception, reviving the all blissful potencies of instincts of dormant feelings; like love, pathos, anger and wonder etc. This all blissful consciousness of our feelings by way of generalization and universalication (Sadharanikaran) is specially termed as Rasa or Aesthetic experience. It is the experience of one’s own self-luminous blissful state of mind (Svanubhuti). Drawn from the external world of Nature and the illuminating flash of intelligence, melts away the frozen state of one’s own mind, washes out other consciousness and changes the mental sphere into all blissful happiness. The constant consciousness in Supreme Happiness is technically or poetically designated by the name of relish (rasa).