Bunch of Javalis (Transliteration, Translation and Notation in English with Audio CD)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAN250 |

| Author: | Dr. Pappu Venugopala Rao |

| Publisher: | THE KARNATIC MUSIC BOOK CENTRE |

| Language: | Transliteration Text With English Translation |

| Edition: | 2011 |

| ISBN: | 9788190657730 |

| Pages: | 244 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 9.5 inch X 7.0 inch |

| Weight | 460 gm |

Book Description

Welcome to the Bunch of Javali-s, a book with 51 Javali-s and an audio CD with 10.

One of the most fascinating compositional type that has found its way into Carnatic Music sometime in and around 19th century is the javali. In course of time javali has become an integral part of the repertoire of Carnatic music and Classical dance. In recent times there has been a lull. It is time that they are brought back in to circulation so that they regain their rightful place both in the ield of music and dance, hence this endeavor.

The word javali has been discussed for its etymology and meaning by several scholars and musicians but with no conclusive result yet. Some people call javali a Kannada word, I believe it to be a Telugu word. My argument is simple and is based on two dominant evidences,

1. Its musical structure and

2. The language in which most of them are written.

We ind totally different opinions expressed by scholars about the origin and evolution of javali-s. Most scholars believe that padam-s with erotic content gave way to javali-s in course of time. Javali-s are erotic by nature. There is no divinity whatsoever in the Srngara that we ind in javali-s. This book comes with an audio CD containing ten javali-s sung by stalwarts representing three generations of musicians.

I assure the readers that this will be a treat for rasika-s and a learning experience for students of music and dance.

Thank you for owning this book and the CD.

Dr. Pappu Venugopala Rao, a well- known scholar, poet, musicologist, Sanskritist, dance expert, writer and orator has more than 18 books on various subjects to his credit. The most recent of his books that have received acclaim are 'Flowers at His Feet', 'Science of Sricakra' and Rasamanjari. Still a dedicated student of Indology, Religion and Philosophy, he has presented and published over 100 research papers. After 32 years of service as academic administrator with the American Institute of Indian Studies, Dr. Rao now holds many important portfolios in prominent institutions, Member, Sangeet Natak Akademi, New Delhi, Member of Experts 1 Committee and Secretary, The Music Academy, Madras, Editor, Journal of the Music Academy, Contributing Editor, Sruti Magazine and Member of the Academic Council, Kalakshetra Foundation, Chennai being few of them. His Literatures on music, dance and literature have received high critical acclaim and an equal amount of appreciation from audiences in general. Dr. Pappu Venugopala Rao is a Visiting Professor at Kalakshetra and the University of Hyderabad among others. He is an adjudicator of Doctoral dissertations in dance, music and literature for a number of Universities across the globe with awards and titles like Sangita Sastra Nidhi, SangTta Sastra Visarada, Sangita Sastra Kovida, Asukavi Sekhara and Best Book Award for Flowers at His Feet, his committed service to the ields of arts and literature continues...

Prologue

We have a vast variety of compositions in the repertoire of carnatic music ranging from sloka- s, vrttam-s, krti-s, tillana-s to bhajan-s. It is amazing to see how this classical form of music embraces each of the genres into its fold. One of the most fascinating compositional type that has found its way into carnatic music sometime in and around 19th century is the javali, In course of time javali has become an integral part of the repertoire of carnatic music and classical dance.

javali-s have a very attractive melody and are usually set to popular raga-s and tala-s. Many of the javali-s are set to adi, rupaka and capu tala-s. khamas, pharaj, jhanjhuti, kapi, behag, hamirkalyani, etc. are some of the raga-s that are employed for the javali-s. Most javali-s consist of a pallavi, an anupallavi and one or more caranam-s. We also find javali-s without anupallavi, and with only one caranam. The lyric is by nature erotic, though some interpret it from the point of view of bhakti or devotion. The style of language of a javali is normally colloquial and may sometimes border on vulgarity. Unlike padam-s, javali-s are sung in fast tempo. The earliest publications of javali-s date back to 1902 where we find only the lyrics of javali-s, like in gayakalocana. The Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini of Subbarama Dikshitar published in 1904, does not carry even one javali. But in the introductory pages of Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini, Subbarama Dikshitar defines javali as a composition which has the characteristics of a daruvu and is set to folk music.

Prof. Sambamurty in his history of indian music mentions javali thus:

"This form had its birth in the nineteenth century. It is a lighter type of composition. There is neither the classic dignity about its music nor is its sahitya of a superior order. There are javalis in telugu and kannada. To lend attraction to the tune, sometimes liberties are taken with the grammar of the raga. Phrases suggestive of other raga-s and phrases foreign to the raga are seen in some javalis like emandune muddu (mukhari raga) and apaduruku (khamas raga)".

Sri Balantarapu Rajanikanta Rao in his Andhra Vaggeyakara Caritramu, mentions javali as a composition which is usually sung after ragam tanam pallavi in a concert. They were absorbed into the repertoire of South Indian classical dances because of their inherent rhythm and tempo, just like the adaptation of padavarnam-s and svarajati-s.

javali-s were composed in plenty during the time of Marathi rulers of Tanjavur and by many others during the period of Swati Tirunal, a junior contemporary of Thyagaraja. It looks like the first javali-s were written during the time of Swati Tirunal and probably by him. Nevertheless it is only fair to give credit to the Tanjore Quartette for the evolution of javali-s and their place today in the compositional types of classical music and dance.

The Tanjore Quartette - Chinnayya (1802-1856), Ponnayya (1804-1864), Sivanandam (1808- 1863) and Vadivelu (1810-1845) have contributed immensely to the dance music of bharatanatyam. They were initially employed in the court of the Maratha king Sarfoji II (1777 -1832) at Tanjavur. Later they moved to Travancore and were patronized by Swati Tirunal (1813-1847). Among them, Chinnayya and Vadivelu learnt music from Muttuswami Dikshitar. Later they became the court musicians of Swati Tirunal. There are some javali-s attributed to Chinnayya. At least 21 javali-s are found to have been written by Chinnayya, eldest among the brothers, two of them addressed to brhadiswara and others dedicated to Mysore Maharaja Chamaraja Wodeyar. Some javali-s for which we do not have any conclusive evidence of the authorship are sometimes attributed to either Chinnayya or Vadivelu.

As of now we don't find javali-s before the period of Swati Tirunal. There are some scholars who bring Melattur Kasinatha Kavi, Veerabhadra Kavi and Kshetrayya into the list of javali composers. This seems a little bit farfetched.

While the form of javali has become well-known during the last 2 centuries, the term java]i still remains enigmatic. Etymologically we do not find enough evidences to understand the word javali. Different dictionaries such as Andhra Dipika of Mamidi Venkatacharyulu (1764- 1834), C.P.Brown Telugu - English dictionary (1903), Vavilla dictionary (1951), Andhra Vachaspatyam (1953), Suryarayandhra Nighantuvu third edition (1981), Kittel's Kannada - English dictionary (1968), Dravidian Etymological dictionary by T. Burrow and M.E. Emeneau, Sangeeta Sabdartha Chandrika (1954), and many other lexicons unanimously and universally define javali-s as erotic songs. The Encyclopedia Britannica volume 27 page 745 mentions 'pada and javali are two kinds of love songs using poetic imagery'.

K.Y. Achar, writing about kannada javali-s (B.U. Press 1977) feels, the word swaravali could have become avali and then java]i where as Dr. Sivaram Karant in his 'Siri Kannada Arthakosh' mentioned javali as a song and also gives another meaning as 'weak in nature'. 'javadi' also means a kind of cream used by women to apply to their hands and feet. We find 'jhavali' being used as a surname and is also the name of a village in Maharashtra. vadi is a word which is equivalent to yati in prosody; yati is a syllable rhyming to the initial letter of a line in poetry after a specific interval; jya is a sanskrt word meaning a bow string. But it is difficult to combine jya and vadi and etymologically explain javali. But K.V. Achar conclusively attempts to establish javali as a kannada word, meaning erotic songs with inherent scope for abhinaya or histrionics.

Prof. Raghavan says that the word javali is seen in the telugu dictionaries printed after 19th century, coinciding with the time of the origin of javali, Dr. S. Sita in her book 'Tanjore as seat of Music' describes javali-s as vulgar lyrics and says that the word originates from kannada.

There are some scholars who go with the nature of javali as a daruvu which conforms to the metric structure of ragada-s, There are ragada-s reflecting the gait of different animals like those of the elephant, bull, horse - dwirada gati ragada, vrsabha gati ragada, and haya gati ragada respectively. The last one has a second variety known as turaga valgana ragada. The metric structure of these ragada-s conforms to the rhythmic structure of catusra jati rupaka, tisra jati eka, sankirna jati jhampa, which are some of the tala-s used for javali-s. Though we cannot conclusively interpret javali-s as lyrics with the gait of a horse, dictionaries indicate javalamu as having the gait of a horse. Therefore, we may probably say that javali has lyrics with a rhythmic structure resembling the gait of a horse, until further research throws more light on this subject.

We find totally different opinions expressed by scholars about the origin and evolution of javali-s. Most scholars believe, truly so, that padam-s with erotic content gave way to javali-s in course of time. Initially, there could have been padam-s in faster tempo as an experiment. And probably reduction in the size of a padam was the beginning of the constructions of javali-s. In fact Sri Rallapalli Ananta Krishna Sarma feels that, in size, a javali is half a padam. Most of them resemble erotic padam-s in their lyric. It is not easy in most cases to differentiate padam-s from javali-s by just looking at the lyrical structure. We also find a few javali-s with almost the same length as that of a pad am and dealing with srngara as in a padam. Though there are some broad classifications and differences between padam-s and javali-s, the lines cannot be clearly drawn. Most javali-s are identified as javali-s by their music rather than by their lyrical structure.

It is interesting that probably all javali composers are invariably men and there are no female javali composers yet.

Dr. Arudra says that javali-s were born in the 19th Century in Travancore, were nourished in Mysore and enjoyed their existence in Tamil Nadu and Andhra. We, of course find many javali-s in Tamil Nadu and Andhra. Balantarapu Rajanikanta Rao in his Andhra Vaggeyakara Caritramu opines that padam-s which were sung initially in couka kalam (slow tempo) could have been sung in madhyama kalam (medium tempo) as an experiment and probably could have been called as javali-s initially. But, we find javali-s firmly established after the period of Swati Tirunal's time in the latter half of 19th century as a compositional form employed in both music and dance.

About the content and nature of javali-s, there are two different interpretations. Some hold them as reflecting the yearning of the jivatma for the paramatma, or union with God, and consider javali-s as sacred compositions, while others treat them as erotic compositions. There are yet others, who feel that initially these were performed by devadasi-s in temples and as they moved out of the temple premises to be performed outside, the dance content degenerated. This gave rise to the opinion that javali-s which were at one point of time sacred, became superficial, erotic and brazen over a period of time. We find that there are javali-s written in kannada around 1800 AD by one Kappani, dedicated to Nanjundeswara. Strangely these javali-s are known as vairagya javali-s, philosophical or spiritual in nature, a distortion of the very definition of the word javali-s, With this exception, javali-s are by far erotic, depicting mostly unfaithful nayika-s or unfaithful nayaka-s.

If we look at the major javali composers and their signature terms or mudra-s, we may tend to believe that javali-s may be erotic songs dedicated to Gods. However a discerning look at the compositions as a whole may prove otherwise. Not withstanding the mudra-s of the composers, I strongly believe, javali-s in general are explicitly erotic in nature with very few exceptions. Any effort to attribute dignity, devotion or sanctity to them is a futile exercise and a farfetched interpretation. A research oriented observation reveals that the content of most javali-s depicts parakiya or samanya nayika-s and daksina or satha nayaka-s.

CONTENTS

| Pattabhiranayya | ||

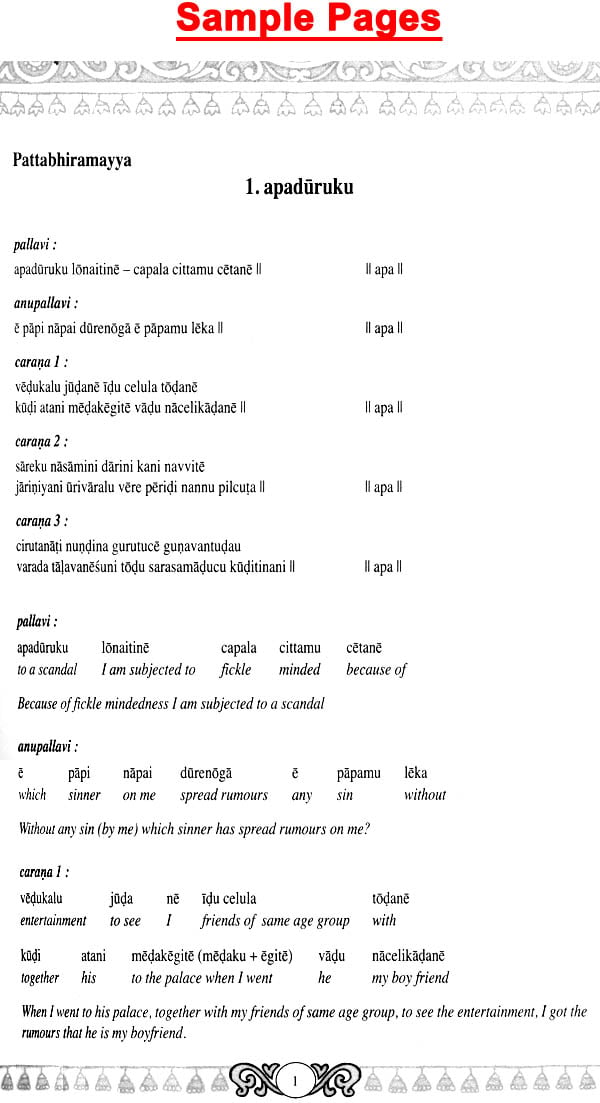

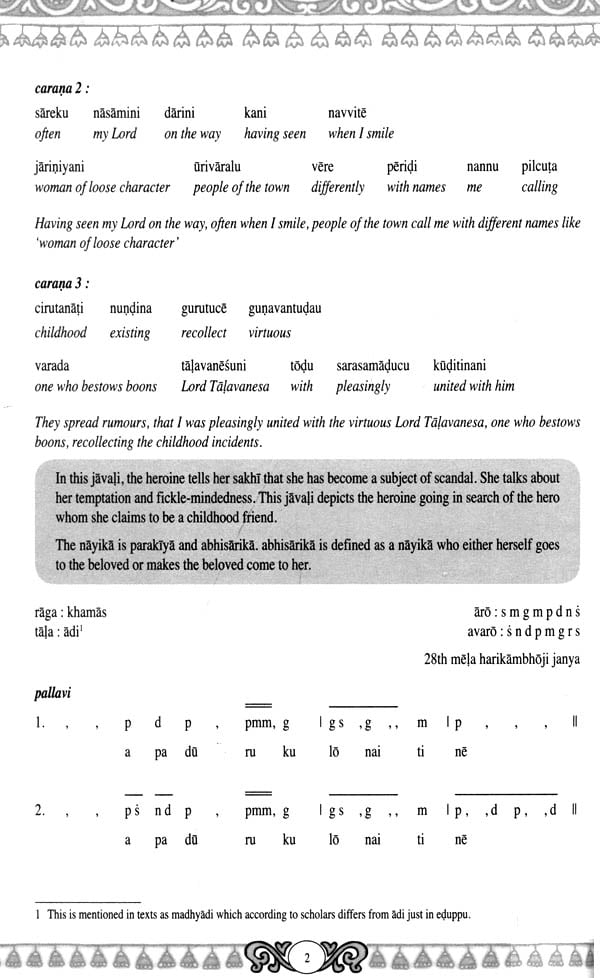

| 1 | apaduruku - khamas | 1 |

| 2 | balimi ela - todi | 4 |

| 3 | emi seyudunate - pharaj | 8 |

| 4 | ilaguna - darbar | 12 |

| 5 | mohamella - mohanam | 18 |

| 6 | nannu culakana jese - vasanta | 22 |

| 7 | nilalana calu - dhanyasi | 25 |

| 8 | paripovalera - bilahari | 28 |

| 9 | rara namminara - kapi | 32 |

| 10 | tarumaru - natakuranji | 35 |

| 11 | telisevagalella - bilahari | 39 |

| Dharmapuri Subbarayar | ||

| 12 | adi nipai - yamuna kalyani | 41 |

| 13 | emandune - mukhari | 44 |

| 14 | era era - khamas | 47 |

| 15 | eratagunatara - kedaragaula | 51 |

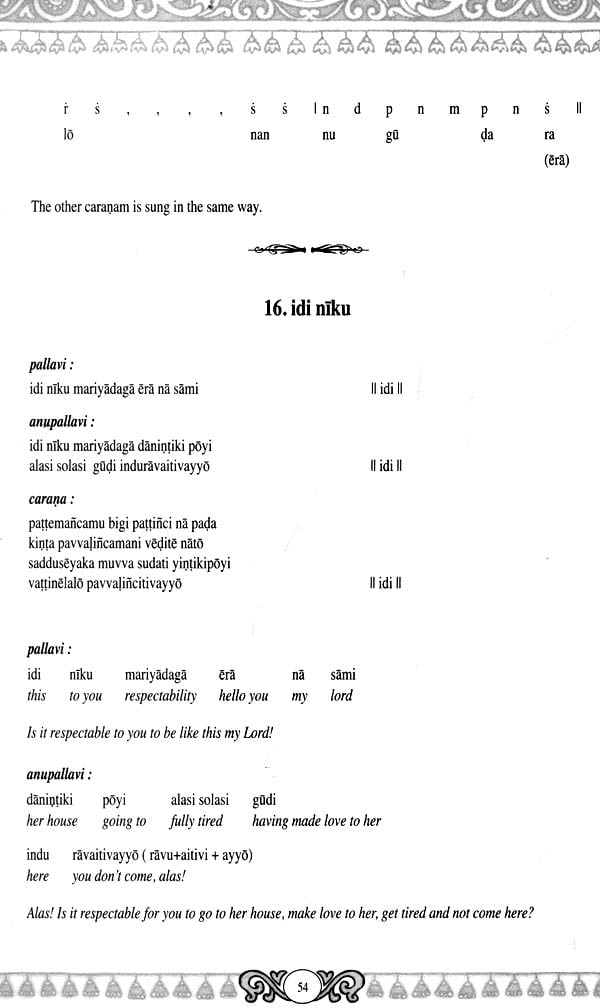

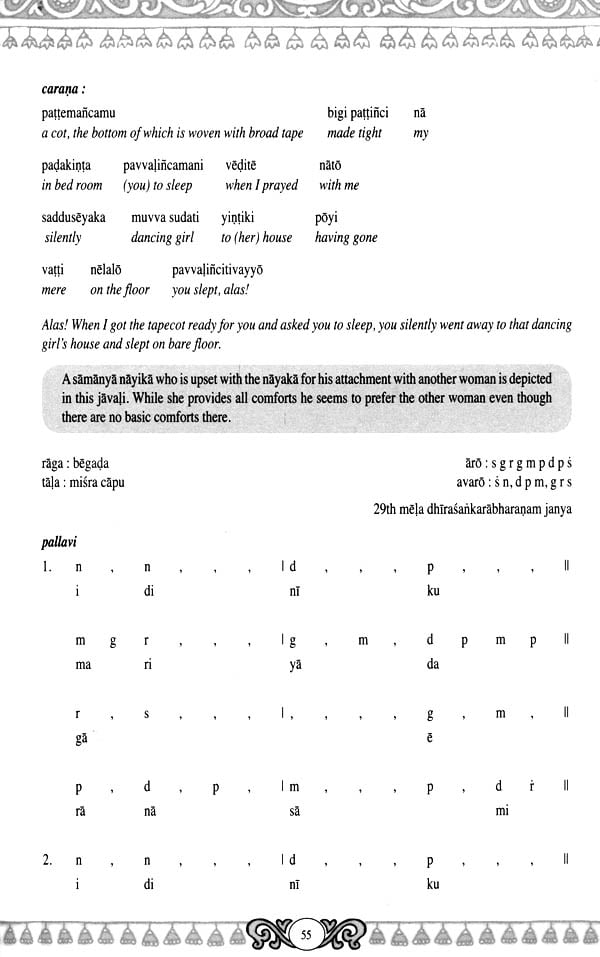

| 16 | idi niku - begada | 54 |

| 17 | kommaro - khamas | 59 |

| 18 | varemi - surati | 63 |

| 19 | vega nivu - surati | 66 |

| Tanjavur Chinnayya | ||

| 20 | kopametula - kedaragaula | 72 |

| 21 | muttavaddura - saveri | 77 |

| 22 | vegatayegade - jhanjhuti | 81 |

| Tirupati Vidyala Narayanaswami Naidu | ||

| 23 | payarani - hindusthani kapi | 86 |

| 24 | telisenura - saveri | 90 |

| Swati Tirunal | ||

| 25 | itu sahasamulu - saindhavi | 96 |

| Patnam Subramaniyer | ||

| 26 | apudu manasu - khamas | 101 |

| 27 | samayamide - behag | 105 |

| Ramanathapuram Srinivasa Iyengar | ||

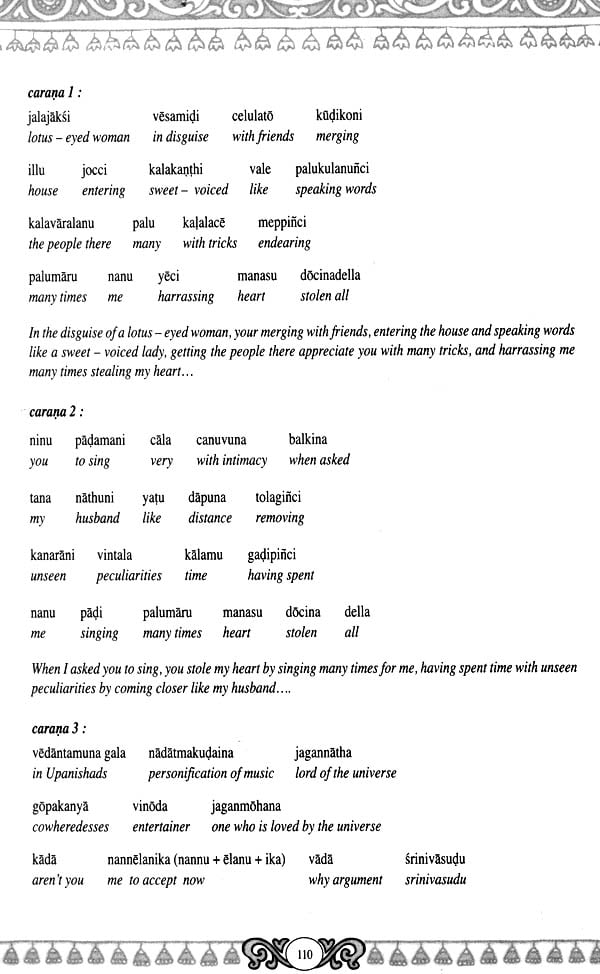

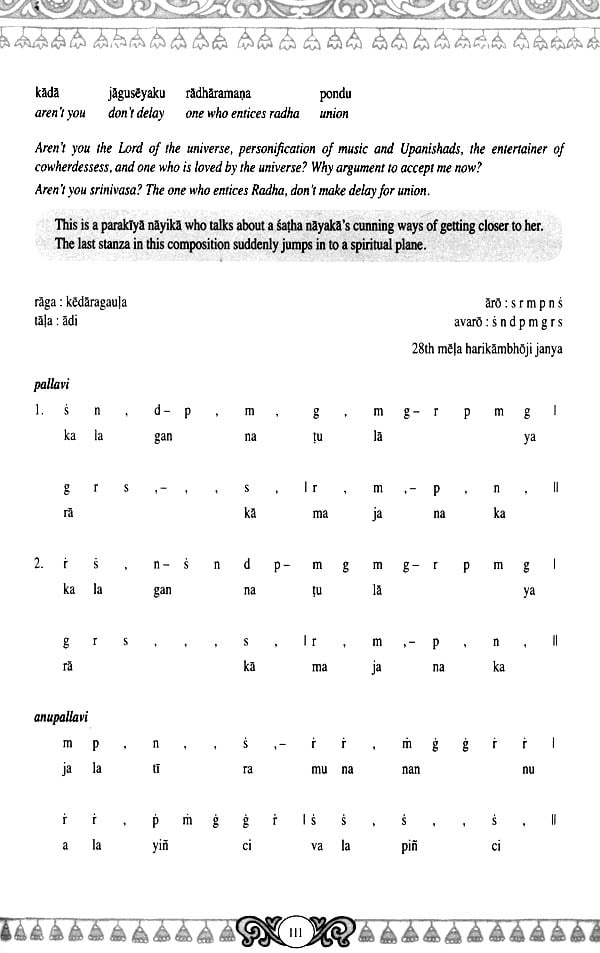

| 28 | kalagannatu - kedaragaula | 109 |

| Banglore Chandrashekhara Shastri | ||

| 29 | ekamini - natakuranji | 113 |

| Venkata Subbarayar | ||

| 30 | nammu vidanaduta - pharaj | 117 |

| Dasu Sreeramulu | ||

| 31 | vanitaro - ananda bhairavi | 119 |

| Patrayani Seetharama Shastri | ||

| 32 | vagala vayyari - kapi | 124 |

| Unknown Authors | ||

| 33 | calamelara - natakuranji | 128 |

| 34 | carumati - kanada | 133 |

| 35 | ela radayane - bhairavi | 137 |

| 36 | emi memu - ananda bhairavi | 140 |

| 37 | iddari pondela - behag | 143 |

| 38 | intirovani - behag | 146 |

| 39 | janatanamu - hindusthani kapi | 149 |

| 40 | kulamulona - sindhu bhairavi | 152 |

| 41 | madhuranagarilo - ananda bhairavi | 156 |

| 42 | mavallagadamma - mand | 159 |

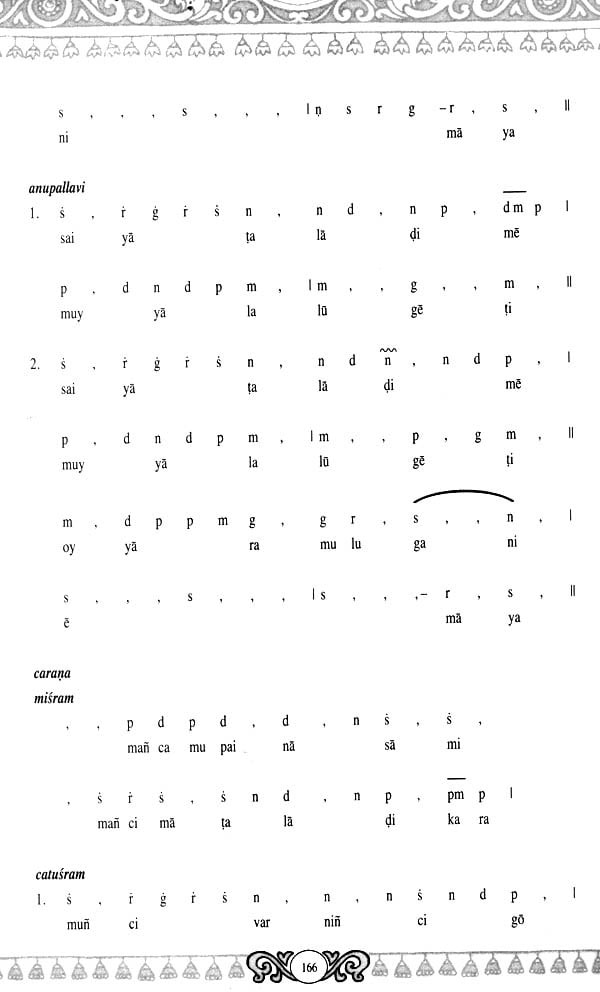

| 43 | mayaladi - todi | 163 |

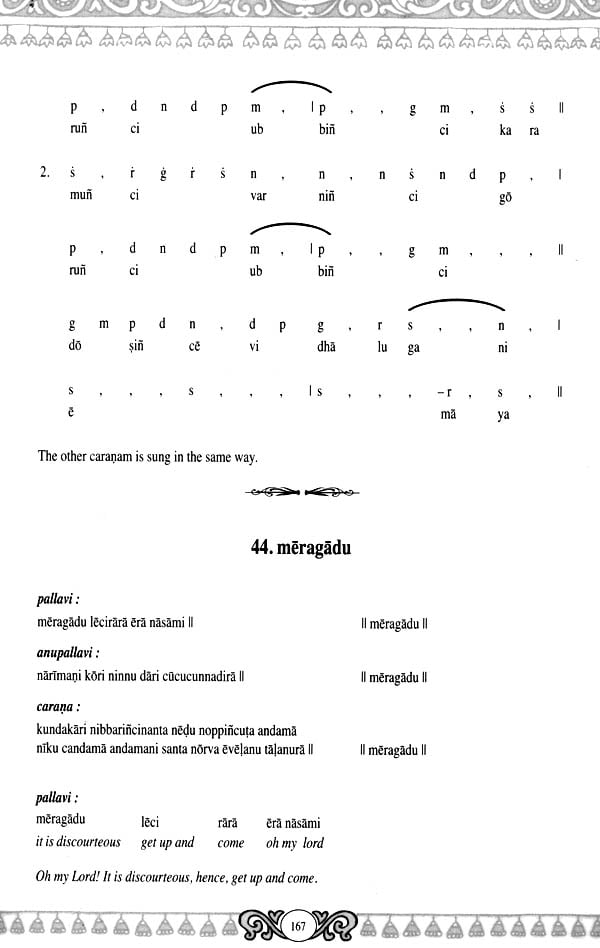

| 44 | meragadu - athana | 167 |

| 45 | mosajesane - todi | 171 |

| 46 | muttaradate - saveri | 174 |

| 47 | ninu ganaka - hamir kalyani | 178 |

| 48 | nirajaksi - desiyatodi | 181 |

| 49 | sarasuni - khamas | 183 |

| 50 | sariyemi - athana | 186 |

| 51 | vaddani nenantini - hidusthani kapi | 190 |

| Appendix | ||

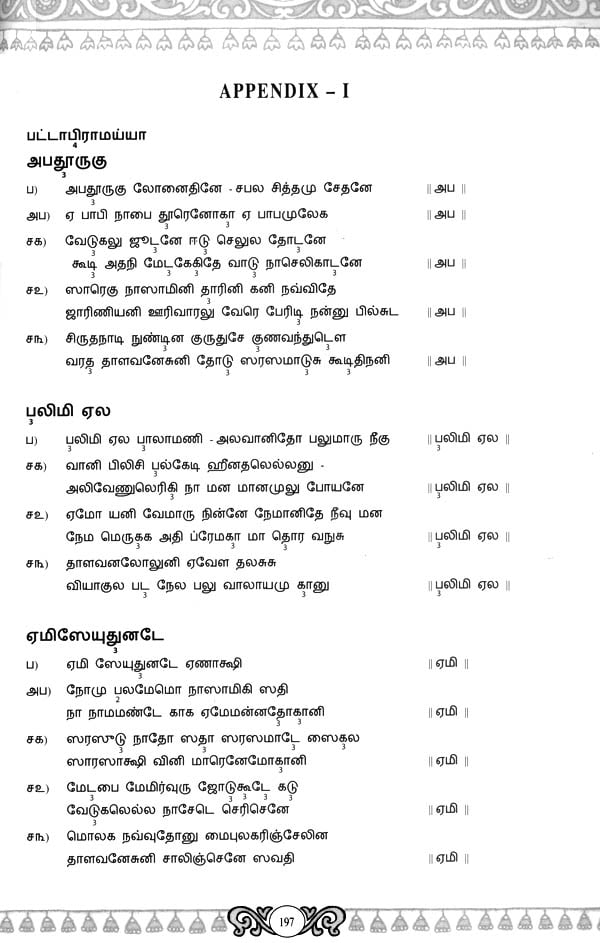

| Appendix I | 197 | |

| Appendix II | 213 | |

| Appendix III | 225 |