Indus to Ganges

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAE750 |

| Author: | G. K. Lama |

| Publisher: | KALA PRAKASHAN |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2009 |

| ISBN: | 9788189921804 |

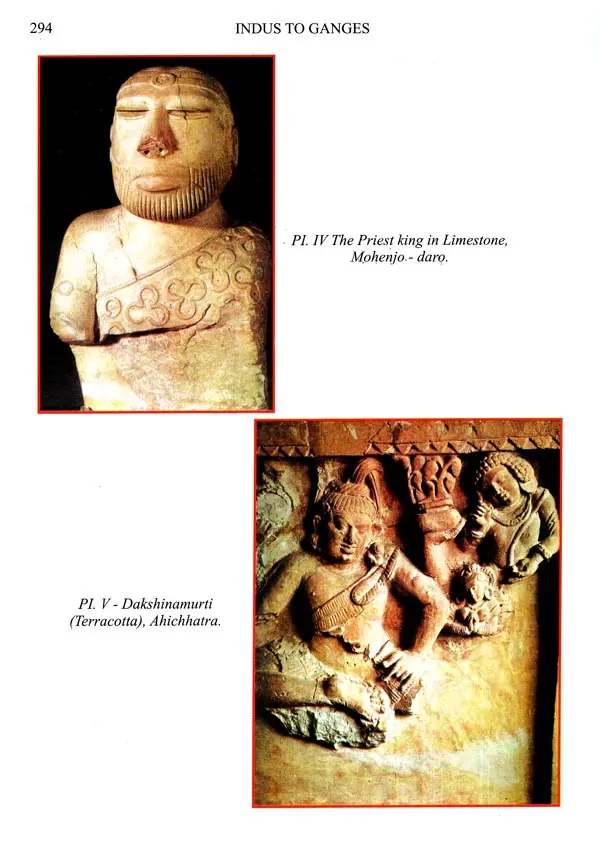

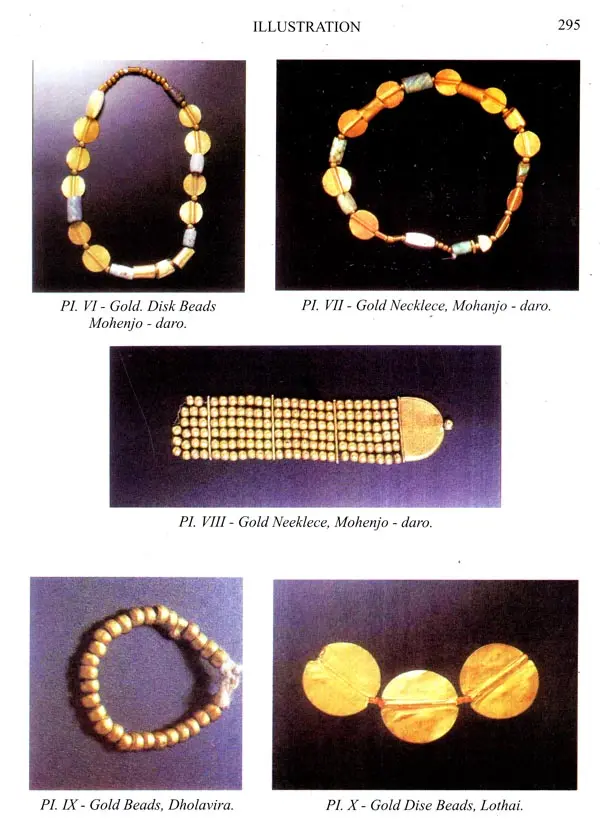

| Pages: | 300 (Throughout Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 11.00 X 9.00 inch |

| Weight | 1.42 kg |

Book Description

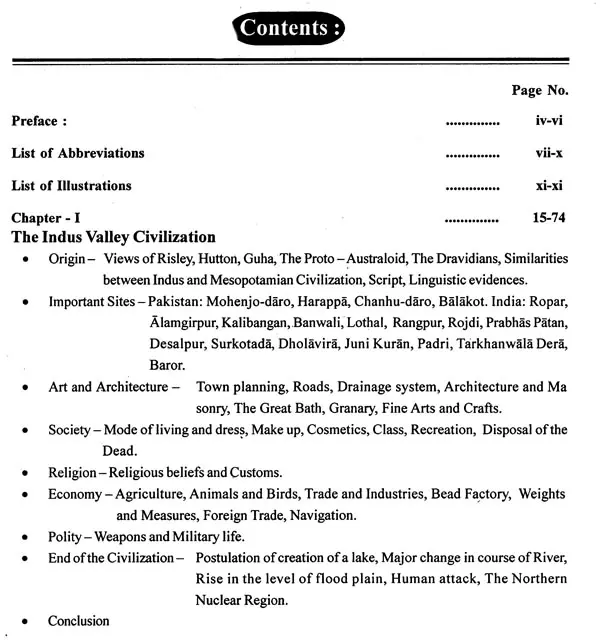

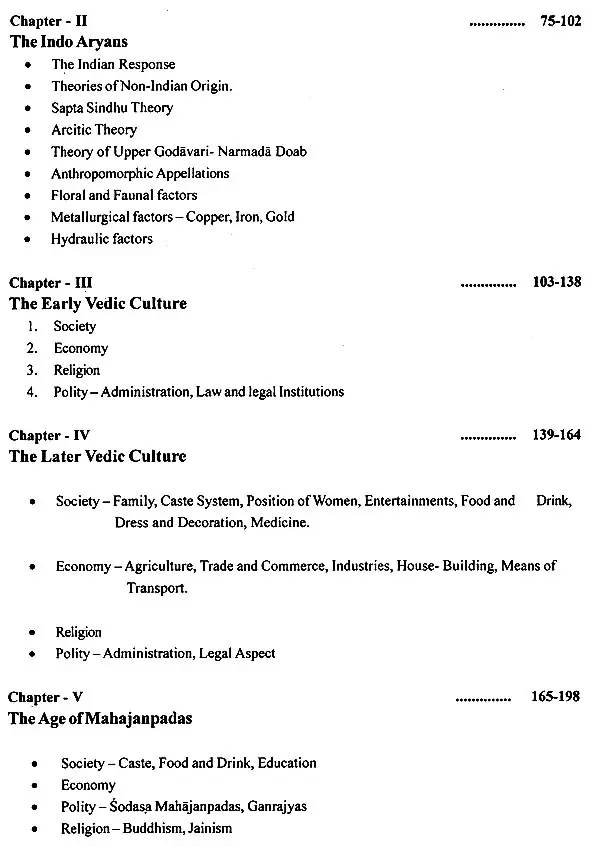

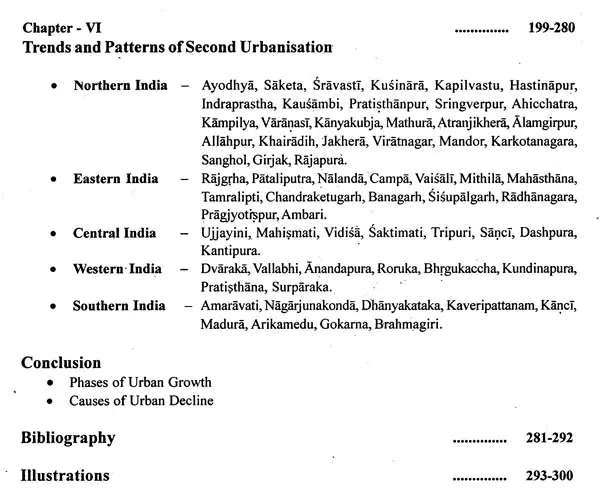

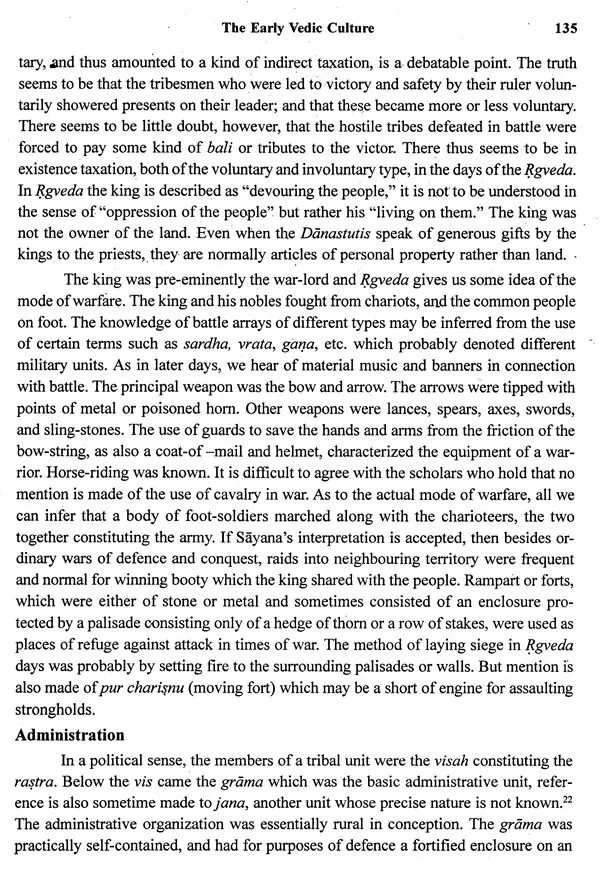

This book gives a full view of the Indian history from the 1st urbanization to the 2nd urbanization. It begins with the history of the origin of the Indus Civilization. It delineates the genesis and growth of urban architecture of the Harappans through the various discoveries from so many sites in the Indian subcontinent. It discusses the society, religion, economy, polity, art and architecture and different causes of the end of the civilization. The book also throws light on the origin of Indo Aryans and cultural development of Early and Later Vedic period. A brief introduction has also been given about the Mahajanpadas and Republics of 6th century BC and lastly focus has been given on the trends and patterns of second urbanization in India. Hope, the book will throw new light on Indian civilization.

Dr. G. K. Lama, Lecturer (Archaeology), Dept. of AIHC & Archaeology, B.H.U., Varanasi has explored and excavated various sites of archaeological importance in eastern and western U.P. He was Co-Director of the exploration work done in western U.P. along the rivers Yamuna and Hindon in 2007. Dr. Lama has presented about two dozen research papers in various national and international seminars and the same numbers of articles have been published in various reputed Journals.

He has five books in his credit, they are:

(i) Tibet Men Bauddha Dharma Ka Itihas.

(ii) Samyak Darshan.

(iii) Cultural Heritage of South-east Asia.

(iv) A Buddhist Universe.

(v) Indus To Ganges.

To be a history in the true sense of the word, the work must be the story of the people inhabiting a country. It must be a record of their life from age to age presented through the life and achievements of men whose exploits become the beacon lights of tradition; through the characteristic reaction of the people to physical and economic conditions; through political changes and vicissitudes which create the forces and conditions which operate upon life; through characteristic social institutions, beliefs and forms; through literary and artistic achievements; through the movements of thought which from time to time helped or hindered the growth of collective harmony; through those values which the people have accepted or reacted to and which created or shaped their collective will; through efforts of the people to will themselves into an organic unity. The central purpose of a history must, therefore, be to investigate and unfold the values which age after age have inspired the inhabitants of a country to develop their collective will and to express it through the manifold activities of their life. Such a history of India is still to be written.

History is being consciously lived by Indians. There is a conscious as well as an unconscious attempt to carry life to perfection, to join the fragments of existence, and to discover the meaning of the visions which they reveal. It is not enough, therefore, to conserve, record and understand what has happened: it is necessary also to assess the nature and direction of the momentous forces working through the life of India in order to appreciate the fulfillment which they seek. In the past, Indians laid little store by history. Our available sources of information are inadequate, and in so far as they are foreign, are almost invariably tainted with a bias towards India's conquerors. Research is meagre and disconnected. Works by ancient Indian authors which throw light on history are few. Religious and literary sources like the puranas and the Kavyas have not yet fully yielded up their chronological or historical wealth. Epigraphic records, though valuable, leave many periods unrelated. Foreign travellers from other countries of Asia and from Europe, like Megasthenes of Greece, Hiuen - Tsang of China, Al-Masudi of Arabia, Manucci of Venice, and Bernier from France, have left valuable glimpses of India, but they are the results of superficial observation, though their value in reconstructing the past is immense.

The attempts of British scholars have hindered rather than helped the study of Indian history. It does not gives us the real India; nor does it present a picture of what we saw, felt and suffered, of how we reacted to foreign influences, or of the values and organizations we created out of the impact with the West. The history of India, as dealt with in most of the works of this kind, naturally, therefore, lacks historical perspective. Unfortunately for us, during the last two hundred years we had not only to study such histories but unconsciously to mould our whole outlook on life upon them. Few people realize that the teaching of such histories in our schools and universities has substantially added to the difficulties which India has had to face during the last hundred years, and never more than during recent years. Generation after generation, during their school or college career, were told about the successive foreign invasions of the country, but little about how we resisted them and less about our victories. They were taught to decry the Hindu social system; but they were not told how this system came into existence as a synthesis of political, social, economic and cultural forces; how it developed in the people the tenacity to survive catastrophic changes of millennia; how it protected life and culture in times of difficulty by its conservative strength and in favourable times developed an elasticity which made ordered progress possible; and how its vitality enabled the national culture to adjust its central ideas to new conditions.

The multiplicity of our languages and communities is widely advertised, but little emphasis is laid on certain facts which make India what she was. Throughout the last two millennia, there was linguistic unity. Some sort of lingua franca was used by a very large part of the country; and Sanskrit, for a thousand years the language of royal courts and at all times the language of culture, was predominant, influencing life, language and literature in most provinces. For over three thousand years, social and family life had been moulded or influenced by the Dharma-Shastra texts, containing a comprehensive code of personal law, which, though adapted from time to time to suit every age and province, provided a continuous unifying social force. Aryan, or rather Hindu culture drew its inspiration in every successive generation from Sanskrit works on religion, philosophy, rituals, law and science, and particularly the two epics, the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and the Bhagavata, under-went recensions from time to time, and became the one irresistible creative force which has shaped the collective spirit of the people.

The older school of historians believed that imperialism of the militaristic political type was unfamiliar to this 'mystic land'. But the Aryan conquest of India was as much militaristic-political as religious and cultural, If instead of treating by dynasties, stress is laid on the rise and fall of Imperial power of Magadhan sovereignty. The history of India is not the story of how she underwent foreign invasions, but how she resisted them and eventually triumphed over them. Traditions of modern historical research founded by British scholars of repute were unfortunately coloured by their attitude towards ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, which have a dead past and are, in a sense, museum exhibits. A postmortem examination of India's past would be scientifically inaccurate; for every period of Indian History is no more than an expression in a limited period of all the life forces and dominant ideas created and preserved by the national culture, which are rushing forward at every moment through time. The modern historian of India must approach her as a living entity with a central continuous urge, of which the apparent life is a more expression.

After all, the contribution of different ages to the evolution of national History and Culture should be the main criterion of their relative importance, though the space devoted to each should also be largely determined by the amount of historical material available. There is no doubt, a dearth of material for the political history of ancient India, but this is to a large extent made up for by the corresponding abundance for the cultural side.