Portrayal of the Woman- In the Art and Literature of the Ancient Deccan

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAG014 |

| Author: | G.B. Deglurkar |

| Publisher: | Publication Scheme, Jaipur |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2004 |

| ISBN: | 8181820029 |

| Pages: | 236 (Throughout Color and B/w Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 11.00 X 9.00 inch |

| Weight | 880 gm |

Book Description

The approach is interpretative and appreciative but in doing so the aesthetic values have not been overlooked.

It is a comprehensive study of the woman as depicted in the art of the ancient Deccan through various roles in life, her tender emotions, her attractive movements and her lofty aspirations.

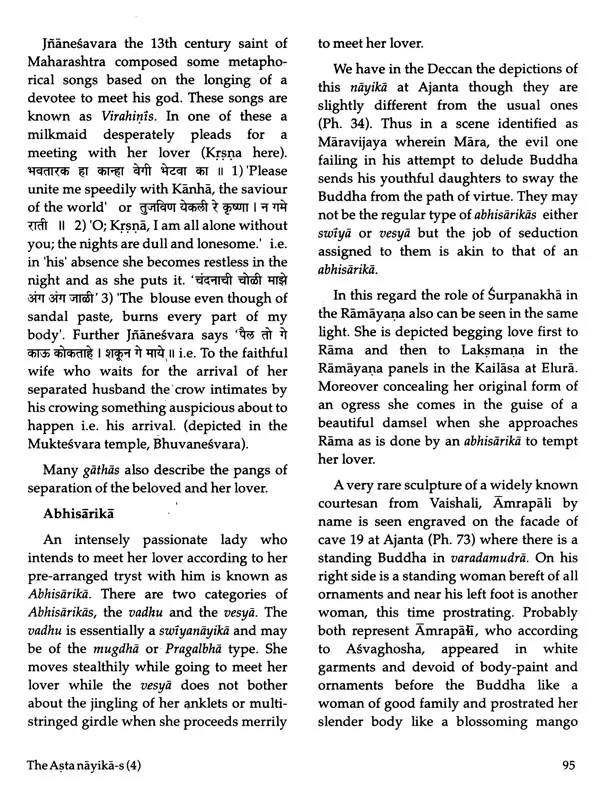

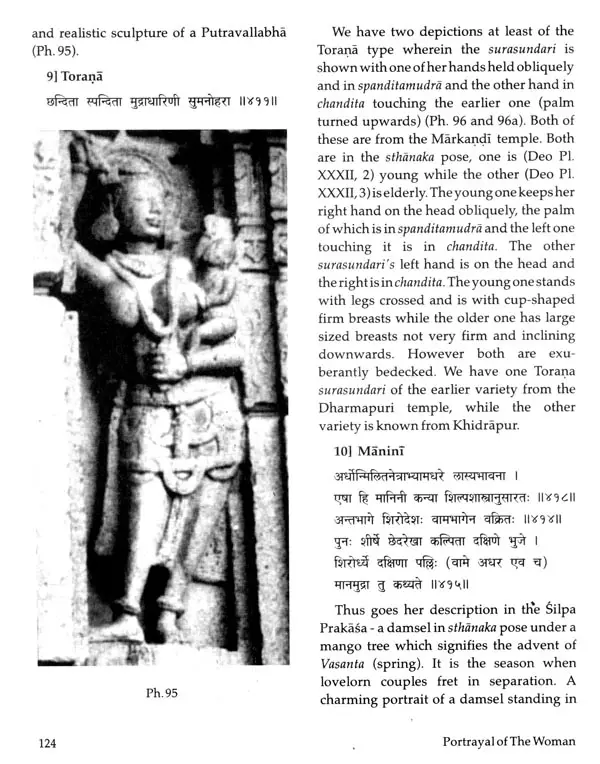

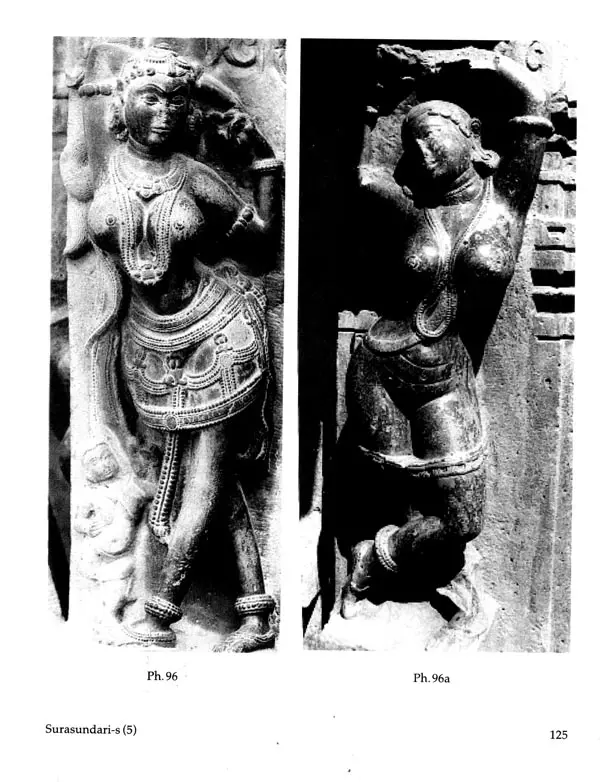

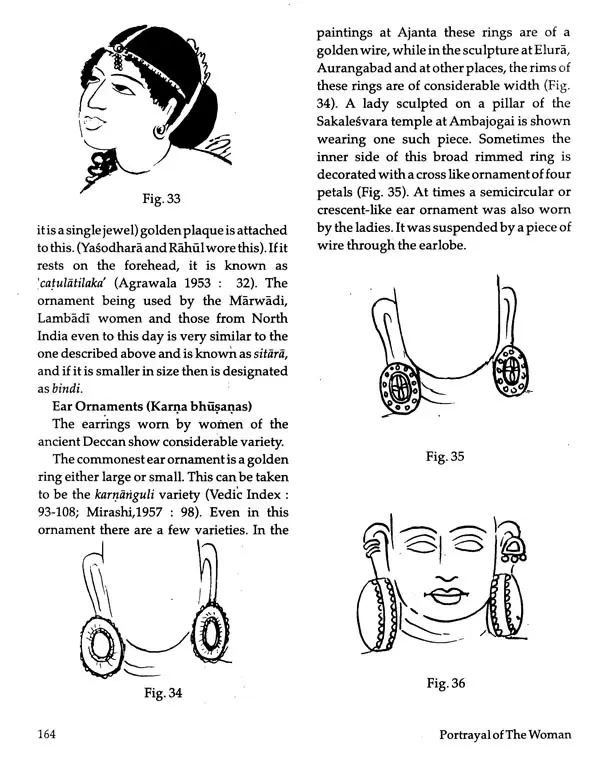

The female sculptures appearing on the walls of the sacred temples demand their legitimate dues. The rich imagination, the almost perfect skills of the artists and the implied significance of the themes carved remain to be looked into. An attempt is therefore made in this work to enrich the study of the female form and its symbolism by including a detailed study of the Ashtanayikas and Surasundaris which have generally escaped the attention of art historians. In addition an entire section, which deals with the emotional responses of women, caught in different situations and moods add rich colors to the entire presentation.

Name any emotion and it is there, be it anxiety, grief, anger, jealousy, bashfulness and love, presenting the inner world of woman which important categories of texts, such as religious and legal are habituated to ignore.

More than 100 photographs and the equal number of sketches enhance the value of the work. It is hoped that the work will be both interesting and informative for the discerning readers.

He is currently appointed by the Govt. of Maharashtra as an expert member on the Board of Management of the Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum, Pune. He is also a member of the Expert Advisory Committee for the export of Non- Antiquities-Mumbai of the Archaeological survey of India.

In the following pages an attempt is made to present the female form in all, its dimensions. Glimpses of a woman's life through paintings and sculptures have been succinctly brought forth as clearly as possible. The approach is interpretative and appreciative but in doing so the aesthetic values have not been overlooked.

It is interesting to observe through the depictions of the woman in art how the artist's conception of the female form developed gradually and how it has been used by him to express varied symbolism, the understanding of which is essential to know the role and significance in different phases of art.

The scholars, and there are many, who have worked on temple architecture, both the rock-cut and structural, have somehow inadequately dealt with the wealth of sculptural forms or iconographical details displayed on the temple walls. The female sculptures appearing on these sacred walls demand their legitimate due. The rich imagination, the almost perfect skill of the artist and the implied significance of the themes carved remains to be looked into. An attempt is therefore made in the following pages to enrich the study of female form by addition of such dimensions as have escaped the attention of the earlier writers so far.

This work is based mainly on the data collected· from various architectural sites visited and studied personally by the present author on different occasions and in different context. Since the work is based mainly on personal observations, consultation of previous works is kept to the minimum. Moreover often quoted Sanskrit verses from the works of stalwarts like Kalidasa, Bana, Harsa, Magha, etc. which appear in earlier works have not been repeated since the connoisseurs of art are very well acquainted with them. Nevertheless the present author owes an immense debt of gratitude to all those who have worked on Indian art providing the solid foundations for works such as the present one.

This study of the woman in the light of new dimensions was possible only because of the munificent two-year fellowship of the K. K. Birla Academy: My sincere thanks are due to the Academy and to Dr. B. N. Tandon who has taken keen academic interest in the completion of the project graciously allowing the use of funds beyond the tenure of the fellowship to ensure its successful completion.

My erstwhile colleague Dr. Gauri Lad has been of great help at various stages of the work, I am thankful to her for the interest she took in the work and for revising the manuscript in respect of language and, style. My student Dr. Jaya Joshi has gone through the entire manuscript and made

She is mute and silent; she nowhere speaks for herself appearing only as a projection of how religion, society and the men who shaped the religion and society would like to see her.

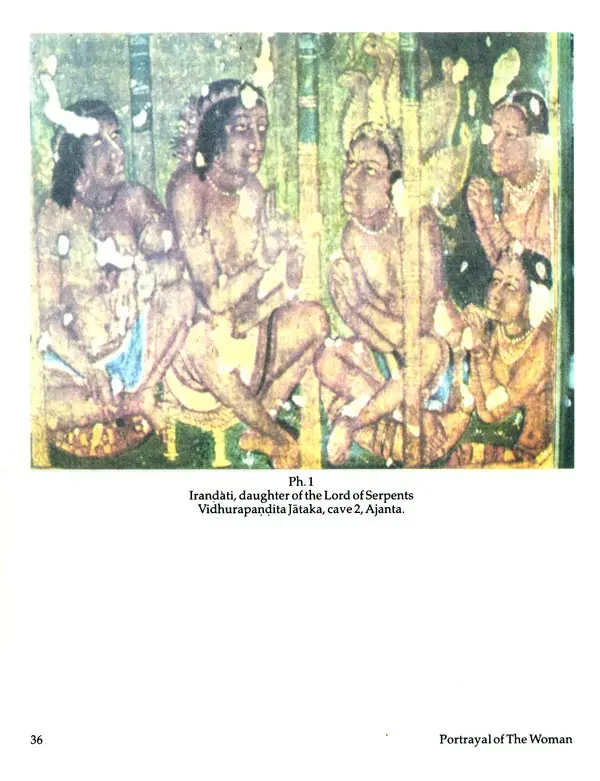

It is against this background that the evidence of the woman as she appears in 'Indian art, whether terracotta, sculptures or paintings, is of crucial importance, to counterbalance the literary portrayal. Indian art, right from. the earliest down to the medieval period, is as much a celebration of woman's physical beauty as of her inner most emotions and feelings, expressed through so much charming gestures and bodily movements. The artists seem to have closed their doors to the literary stereotypes of the obedient daughter, the devoted wife and eternally succoring mother. Instead for the artist any and every woman whether a goddess,' a queen, a dancing girl or a maid servant is an image of beauty, grace and sensuality. The unabashed voluptuousness of the physical form, matched by the elegance of movements and the serenity of expressions are the creation of exquisite artistic skills. But for the Indian artist, the 'other woman', of flesh-and-blood would never have been known to us.

It is no coincidence that when the best of sculptures start making their appearance, a new form of creative literature, poetry and drama also arrives on the scene. The poets and dramatists, Sanskrit and Part, vie with each other to create 'a new woman', young, beautiful and erotic. The urbanity and prosperity brought about by trade and commerce with its consequent patronage was mainly responsible for the 'new woman'. The security, prosperity and exuberance of material culture automatically reflected itself in a desire for everything attractive, beautiful and sublime, be it the physical body or the inner thoughts and emotions. The artist has made full use of the patronage available to him to enliven the world of his patrons and his beholders. As far as the Deccan was concerned the Satavahana phase of its history was one of the most prosperous in terms of trade and commerce and consequent stability. The regional patrons, the Vakatakas, Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, Yadavas and Kakatiyas contributed in their own way to periods of material well-being reflected, in artistic expressions of conspicuous beauty.

The artist of the ancient Deccan has given to posterity a personified life-history of the women of this region. In fact plastic art in the Deccan, as in India has helped till the gaps in the life-history of women. To treat art as , either a pastime or a luxury is not to properly understand its importance.

Art adds a special dimension to the factual and tangible study of life in any given period and region. Like a sensitive seismograph art registers delicate. emotions, deep desires, tender fears, sharp attitudes of the men and women it portrays allowing the artist to give concrete form to thoughts and feelings that excite him.

Book's Contents and Sample Pages