Best of Faiz (Selected Poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz) (Urdu text,transliteration and English translation)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAD235 |

| Author: | Kuldeep Salil |

| Publisher: | Rajpal and Sons |

| Language: | Urdu text,transliteration and English translation |

| Edition: | 2022 |

| ISBN: | 9788170287919 |

| Pages: | 173 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.8 inch |

| Weight | 360 gm |

Book Description

Faiz Ahmed Faiz is the most famous contemporary Urdu poet of the twentieth century who appeals both to the common man as well as the elite connoisseurs of poetry. In the matter of style Faiz can be called the inheritor of the traditkn of Ghalib because of his writing style of gazals whiëh reflects a strong influence of the Persian style and diction. At the same time several of his poems are written in simple conversational style dealing with the problems of the common man. Faiz was committed poet who regarded poetry as a vehicle of serious thought rather than just a pleasurable pastime and often used his poetry to champion the cause of socialistic humanism.

Born in Sialkot in 1911, Faiz began his career as a lecturer in English but soon after turned to journalism where he excelled himself rising to the post of editor of The Pakistan Times. In 1951 the Pakistan government sentenced him to four years imprisonment on the charges of complicity in a failed coup attempt known as the Rawalpindi Conspiracy case. While in jail he wrote two of his greatest works Dastae-Saba and Zindan-Nama. During the regime of Zia-ul Haq he was forced into exile to Beirut. He returned to Pakistan in 1982 and two years laterhe passed away.

This book offers a select 1 of the best of Fais gazals and poems alongwith theif translations as well as transliterations so you can enjoy the beauty and richness of the Urdu language as you read the English transliteration while the translation helps you understand the meaning with all its subtle nuances.

Faiz’s poetry portrays peoples’ lives, their hopes and aspirations, their heartbreaks, hardships and frustrations with a rare elegance and beauty And his lyricism lends a unique charm to that poetry. Also, Faiz’s poetry reflects the noblest human sentiments and values in the midst of gloom engendered by the exploitation and oppression masses and their miserable life.

The depth and delicacy of Fai2’s poetry, owes a lot to his deep study of classical literature. According to Firaq Gorakhpuri, Faiz bletids love- experience with struggle-related social issues, endowing Urdu poetry with a new splendour and introducing in his love poetry a completely new and acceptable element. Coming from Firaq, who is himself a master of love poetry, this is a great compliment.

Born in Sialkot in West Punjab on 11th February, 1911. Faiz was mild mannered, sott-spoken man who would rather let others talk than talk himself.

Kuldip Salil was born on 30th December, 1938 in Sialkot (Pakistan). He took post-graduate degree in English and Economics from Delhi University. He has published four collections of poetry; ‘Bees SalKa Safar’ (1979), ‘Havas Ke ShaherMein’ (1987), ‘Jo KehNa Sake’ (2000) and ‘Awaz Ka Rishta’ (2004), the last three being ghazal collections. He has also published ‘Angrezi Ke Shreshth Kavi Aur Unki Shreshth Kavitayen’, an anthology of best-known English poems in Hindi verse translation.

His latest books are ‘Diwan-e-Ghalib-A Selection’, selected ghazals of Mirza Ghalib translated into English and ‘A Treasury of Urdu Poetry’, translation into English verse of more than one hundred nazms and ghaaals, selected from the works of thirty four Urdu poets, along with their life sketches and brief critical introductions. He has also published a large number of poems (mostly in Khushwant Singh’s column) in various newspapers and journals.

Kuklip Sahl retired as Reader in English from Hans Raj College; Delhi University He won the Delhi Hindi Academy Award for poetry in 1987.

punjab has produced a number of great poets, not only in Punjabi and its various dialects, but in Urdu as well. Of the Urdu poets, two names stand out and vie with the best in the language. Most obviously, they are Mohammed Iqbal and Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Faiz was twenty seven years old when Iqbal died and it can be said without hesitation that the mantle of greatness, passed on from one to the other. Faiz, who was a great admirer of Iqbal, is indeed the greatest Urdu poet after Mir, Ghalib and Iqbal. Sajjad Zahir, a noted writer and critic, writing on just one of the poetic collections of Faiz, ‘Dast-eSaba’, says that it was the most important event of 1953 in Pakistan.

Born in Sialkot in West Punjab on 11th February, 1911, Faiz was a mild mannered, soft-spoken man who would rather let others talk than talk himself. His father, Sultan Mohammed Khan was a lawyer who had earlier served Amir Abdul Rehman in Afghanistan and had acquired courtly habits. Later, he in- cuffed the displeasure of his master, and had to flee Afghanistan. His next port of call was England from where he took his degree in law and came back to his native country. Like his father, Faiz too was an adventurer, but he was a traveller more of the mind than space. He read books and journals and travellers’ tales and attained a firm grounding in the ideas and cross-currents of the nineteenth century. He was rooted in his soil rather than travelling to Europe, as was the fashion among the scions of well-to-do families those days, and as his famed predecessor Mohammed Iqbal had done. He breathed the air of his country and knew its people more intimately than most others.

Sultan Mohammed died in 1931 and his landed property became a subject of litigation among Faiz’s brothers. The poet scrupulously kept away from all this. He, in fact, left the village along with his mother. Much later, in 1955 when his brother died, he went back to the village and distributed the land among the tillers, retaining only half an acre for himself and his dependants.

Ineptitude for the affairs of the world is a well-known trait of most creative artists. Ghalib put it succulently when he said:

Worrying about the world, I wrack my brain

o for a man like me, an endeavour how vain

Faiz gave proof of this quite early in life. Indolence seems to be another quality shared by many poets. John Keats is the best example of it. Faiz says that one thing he found very difficult was replying to letters. Unlike many other poets, however, Faiz was averse to self-projection. “I hate to speak about myself,” he says, “So much so that I avoid the use of first person singular I always use ‘we’ for this.” He was a shy person, who unlike Iqbal and Firaq, recited his poems quite badly. It was, of course, more than made by the quality of his verse.

Faiz’s early education like’ that of most children from Muslim families started with recitations from the Quran and the study of Urdu, Persian and Arabic. The word ‘Faiz’ means bounty. Apart from studies and love of poetry, Faiz Ahmed Faiz was interested in dawdling and playing cricket, among other things. He was first admitted to the madarsa of Maulvi Ibrahim and later moved to Scot Mission School after which hejoined Murray College, Sialkot For higher studies, he went to Govt. College Lahore, from where he took BA (H) degree in Arabic in 1931. He obtained a Master’s degree in English literature in 1933. He post-ratuated in Arabic also.

Before coming to Lahore, Faiz was already feasting on the poetry of Mir, Ghalib and Daagh. At Murray College in Sialkot, Faiz tried his hand at writing poetry in English, apart from Urdu poetry. He was a voracious reader of the novels of Dickens and Hardy.

In Lahore, Faiz got greatly immersed in the cultural and intellectual atmosphere of the Govt. College, where among his teachers and friends were Pitras Bukhari of All India Radio fame and eminent poets and critics like Mohammed-ul-din Taseer and Sufi Ghulam Mohammed Tabassum. Also, he came in close touch with Hafeez Jallandhri, Akhtar Sheerani, Chirag Hasan Salik and Imtiaz Ali Taaj—all well known in their field. It was under the influence of Hafeez Jallandhri, Akhtar Sheerani and Hasrat Mohani that Faiz started writing poetry. Those were leisurely times and educated young men could indulge in long hours of debate in the coffee house and on the bank of river Ravi in the moonlight.

After finishing his studies, Faiz joined Oriental College Amritsar in 1935 as lecturer in English. He later took up lecturership in the same subject at Hailey College of Commerce, Lahore. In 1941, Faiz married Alys George, an English socialist. Alys was a woman of remarkable character, who was a friend and companion to Faiz. She and their two daughters gave stability to his otherwise tumultuous life. Faiz was once invited to speak on Shakespeare in a womens’ college where a screen stood between the speaker and the audience. He felt both amused and indignant. In such an atmosphere marriage with Alys was indeed a blessing.

In 1941, Faiz resigned his teaching job and joined the British Indian Army, more out of his hostility towards Fascism than any loyalty to the British. In 1947, he resigned from the army and took up the editorship of ‘Pakistan Times’ and ‘Imroze’, both progressive papers.

Four years later in 1951 an event took place which not only changed the course of Faiz’s life but also put his life in great danger. Faiz, alongwith Sajjad Zaheer, a leading light of Progressive Writers’ movement in India, and two other army officers was arrested on charges of complicity to overthrow the legally established government of Pakistan. He was sentenced to more than four years of rigorous imprisonment, out of which, he was in solitary confinement for three months. These three months he spent in Sargodha and Layalpur jails, where he was completely cut off from the outside world; not even his wife and children were allowed to meet him.

During the trial, though his life always hung in a balance. On the final day of that trial he was actually told by his lawyer that he would most probably get death sentence. Faiz, not only remained calm, he did not show any anxiety at all. He smoked and laughed and joked with his fellow prisoners as before, say some of the other inmates in the jail. According to one inmate while outside, it was cries of ‘death for the traitors,’ inside the jail, Faiz and colleagues were on a virtual picnic.

I will be free from worrying about gain and loss at least

And will not have to please all and sundry,

I may or may not get wine in hell

I shall be at least rid of the Sheikhji

These years of incarceration, however turned out be kind of a blessing in disguise for Faiz. They were, creatively the most fruitful years of his life. A large number of poems of ‘Daste-Saba’ and ‘Zindan Nama’ were written in this period and remain the crown of his poetic achievement. It was in the cOurse of the trial in the conspiracy case, known as the Rawalpindi case, that he read out this famous couplet:

That which was never a part of the story

That bit has piqued him immensely

and made the judge speechless.

Life in the jail, however, can at times be nerve-wrecking and can even lead to mental breakdown. As a safety valve, some of Faiz’s fellow prisoners tended to quarrel and created ruckus. In these circumstances, poetry writing came as a great relief for Faiz. But life in the jail certainly took its toll. This is evident from many a couplet, though he tried to put up a brave front and used the experience to good account:

Those who have pledged firm loyalty to you

Make light of the sufferings that this path entails

Faiz was ultimately released from jail in April 1955 and soon after that he resumed the editorship of ‘Pakistan Time& and ‘Imroz’. In 1956, he attended the Afro-Asian writers’ conference in Tashkent. In the meantime, there was an army coup in Pakistan when General Ayub Khan ousted Iskandar Mirza in 1958. Consequent upon this coup, Faiz’s progressive papers were taken over by the martial law regime and Faiz was once again arrested in 1959. Making false cases against individuals, was not uncommon those days. Even in the Rawalpindi conspiracy case, the government prosecutor himself later told Faiz and his collegues in the jail that while it was true that they had met, talked and decided not to stage the coup, they had failed to destroy their papers, which were seized by the government and a mountain was made of a molehill. The reason, according to Major General Akbar Khan, was that the government was not happy with some of military officers and wanted to get rid of them and their friends.

Faiz who had been arrested by the martial law regime under the Safety Law was released in 1959. In the same year, he was appointed the Secretary of Lahore Arts Council, a position he held till 1962. In this year, he won Lenin Peace Prize and in the next, travelled extensively to Egypt, Lebanon, Algeria, Hungary, England and Russia. In 1965, he joined the Department of Information as honorary adviser. Later he was associated with the Institute of Literature and Culture. During the premiership of Benazir. Bhutto, Faiz won Pakistan’s highest award Nishane-Pakistan. This award was given posthumously. He was an active member of Afro-Asian Writers’ Council and worked for their journal ‘Lotus.’

In 1977, Pakistan saw another army coup, the third, in which General Zia-Ul-Haq overthrew the regime of Zulfikar Au Bhutto. Faiz’s poetry was banned on Pakistan radio and TV. He went into a voluntary exile and was away from Pakistan from 1978 to 1982 alongwith his wife. During this period, he spent some time in Beirut when the Palestenian struggle was at its peak, and wrote some of his most moving poems:

Lullaby for Palestinian Children

Do not cry, my child

Your mother has just slept after weeping a long while,

Do not cry, my child

Only some time back, your father has departed

Relieved of all sorrow,

Do not cry my child,

Your brother is away to an alien land

And your sister has gone away the same way,

Do not cry my child,

They have just bathed the dead sun and buried the moon

Do not cry my child,

For, f you cry,

Your mother, father, brother and sister

Along with the sun and the moon

Will make you cry all the more.

And f you smile

There is a real possibility.

That all of them in disguise

Will come and play with you.

in your courtyard,

Faiz had a mission to fulfill - the raising of peoples’ awareness, not only in the sub-continent but the world over. In this sense, he was citizen of the world and the entire world was his stage. In any case, great men and creative geniuses belong to all mankind.

In 1982, Faiz returned to Pakistan. He was suffering from asthma which was aggravated by his unsettled life and disturbed existence. In 1984, he fell ill and was admitted to Mayo Hospital, Lahore where he passed away on 30th November, 1984. Both progressives and conservatives were keen to own him up and show that Faiz was their poet. There were slogans both of ‘Inqlab Zindabad’ and ‘Nara-e-Tadbeer’. In this context one is reminded of Kabir, after whose death both Hindus and Muslims vied with each other to claim that he belonged to them.

Faiz’s poetry portrays people’s lives, their hopes and aspirations, their heartbreaks, hardships and frustrations with a rare elegance and beauty. And his lyricism lends a unique charm to that poetry. Also, Faiz’s poetry reflects the noblest human sentiments and values in the midst of gloom engendered by the exploitation and oppression of the masses and their miserable life. And these values are perfectly in consonance with the time- tested values of the sub-continent.

According to a senior critic, Asar Lakhnavi, Faiz is the greatest progressive poet; his imagination and art raised his verse to great heights. He has presented delicate feelings in an exquisite form. His popularity in both India and Pakistan and the world over is a testimony not only to his greatness but also his ability to establish a rapport with the people. In fact, he is a people’s poet.

The depth and delicacy of Faiz’s poetry, owes a lot to his deep study of classial literature. According to Firaq Gorakhpuri, Faiz blends his love-experience with struggle-related social issues, endowing Urdu poetry with a new splendour and introducing in his love poetry a completely new and acceptable element. Coming from Firaq, who is himself a master of love poetry, this is a great compliment.

Faiz’s poetry received strength and sustenance from the plight of the common people and their struggle to improve their lot. He championed their cause most eloquently. The poignancy and power of his poetry derives largely from a blend of his boundless love for groaning humanity and his personal sufferings! It is a poetry not only genuine and spontaneous, it has an authenticity about it which wins a ready response from the audience.

Another reason for the tremendous appeal of his poetry is a glimpse of hope for the bright dawn, born out of the womb of the night of gloom, the night symbolizing oppression, helplessness and sufferings. It is not a Utopia that Faiz is presenting; it is a light after having gone through the tunnel, a triumphal glimpse after a struggle, at least on the mental plane. And courage perseverance and call to the collective might of the people are the weapons of this struggle Press on, for the destination has not yet arrived

He suffered, but he hoped that the struggle and sufferings will not go in vain:

Whatever befell us, 0 evening of separation, was part of the game But our tears brightened you up all the same

Faiz perfected the art of presenting contemporary themes in the classical garb. He uses conventional images, symbols and metaphors of Urdu poetry to express contemporary concerns. And he invests these images and symbols with new meanings. A great admirer of Ghalib and classical scholars and poets, he knew, as we all know, how great a sway the ghazal has had on all lovers of poetry from eighteenth century onwards. So, he wrote not only fascinating ghazals observing all its rules, even his nazms have a sweetness and charm of the ghazal. Of course, whenever necessary, he uses free verse also, but even his free verse reads like good poetry rather than perverted prose. In fact, he was instinctively against prose poetry. He said he did not understand it; it should rather be called poetic prose.

Faiz was a leading light of the Progressive Writers’ Association, a movement launched at a convention in Lucknow in 1936 presided over by Munshj Premchand. It was a movement that spans about half a century and dominated the literary scene in the sub-continent. Apart from political reasons, socialism was a new mantra that the idealists could use against the enemies of communalism—which was spreading fast in Punjab and elsewhere - by uniting the people against the common enemy— poverty. Almost a decade before partition, communal riots had started erupting in the sub-continent. PWA was catching the imagination of the writers, and Faiz was an active member of its Punjab branch. He spent his evenings teaching workers the three R’s and elementary politics. It was a good means of remaining in touch with the people and knowing their life at first hand.

He has been called ‘enlightened human socialist’ by some people. His socialism is not dogmatic; it adapts to the needs of the times. His papers ‘Pakistan Times’ and ‘Imroze’ became a mouthpiece of progressive views and protest against anti-people policies of the state. He was the president of Pakistan Peace Committee and Trade Union until his arrest in 1951.

Faiz was a committed writer, a champion of the neglected and downtrodden with a burning desire to change the social order. He was a socialist by conviction and paid a heavy price for this conviction. He was, attacked not only by his opponents who charged him with treason and sent him to jail, but even by his own people, his comrades and fellow socialists. As great a poet as Au Sardar Jafri, who is himself a great champion of the socialist cause, launched a scathing attack on Faiz, saying that the kind of poetry that Faiz was writing could be written by any “Jan Sanghi or Muslim League” poet. Says Faiz:

Moist eyes are not enough, not the tortured soul,

Nor would the allegation of concealed love do

Go to the marketplace in fetters today

Who else is pure enough in the city of the beloved Except us

To win the assassin hand ?

Take your sorrowing heart with you, let’s go Once again

O comrades, let’s go and be slain

And this hostility came inspite of Faiz’s unshakable belief that poetry must serve a cause; it should serve as a “beacon to poor humanity’s afflicted will” and must not merely display flights of fancy and ornamental skills. The attack by Sardar Jafri and some other progressive writers was indeed an unkind cut, although one cannot accuse Jafri of jealousy.

Although, as the cliche goes, comparisons are odious, it is tempting to compare Faiz with at least one of his contempories and one great predecessor. The contemporary was Firaq Gorakhpuri. Firaq is a great modern poet of the ghazal and one of the greatest in the genre. He has sometime been called the emperor of the ghazal which remains his forte, in spite of the fact that he wrote some good nazms and a large number of rubais, some of which are most memorable. Faiz, on the other hand, though he is equally good in his ghazals, has a place of pre eminence in Urdu poetry because of nazms. If Firaq has a demon in the heart, which must come out through his poetry, Faiz is fired by a mission. Firaq is essentially a poet of the individual, a poet of the restless mind, whereas Faiz is looking outside in the society around. Both are progressive poets, but in their own way.

One more difference between the two is that, while in Faiz, one cannot pick out many poems and say that they are below a certain level and should not have formed part of his published work, it is not so in the case of Firaq. Many of his early poems are indeed sub standard; they look like the work of a learner and should not have been included in his collections.

Another point of difference between Firaq and Faiz is that the f’orrner is largely a poet of love and beauty, and in this he scales great heights. He has the power to stir your imagination and make it soar We came to the tavern in a playful mood, 0 Firaq But became serious after we had drunk wine Faiz, as against this, presents a wonderful blend of love poetry and poetry of social concern. Both Faiz and Firaq have given Urdu poetry some memorable poems, though in Firaq’s case his output is uneven. Perhaps Firaq wrote his best poems in his later life, as hinted earlier, whereas Faiz has written great nazms and ghazals both in his later and early period particularly when he was in jail. His later poetry acquires a new power because of transnational concerns, especially when Pakistan lost its eastern part, and East Bengal had great resentment against Pakistan.

The predecessor to be compared with Faiz is Mohammed Iqbal. Both Faiz and Iqbal were dissatisfied with the prevailing state of affairs; they were critics of society and sought to change it. Both were fired by an overriding and compelling faith. A remarkable thing about Faiz and Iqbal is that both succeed in transforming the raw day-to-day events into great poetry. For Iqbal, however the new millennium lay in his vision of a revival and renewal of Muslims and a pan Islamic movement, whereas for Faiz, the panecea lies in socialism. Iqbal recalled the memories of Muslims, the world conquerors, Faiz seeks a synthesis between woes of the hard-pressed toiling classes and the grief of the lovers. Both sought a world vision to sustain their work but these visions are different. If a philosophical framework for Faiz is to be found in Karl Marx, Iqbal too had admired Marx in more than one poem, but his emphasis was elsewhere.

One of the major differences between Faiz and Iqbal is that whereas Iqbal is direct, ardent and impetuous, Faiz is soft and suggestive. Unlike Iqbal, he is not a god, speaking down to his awe-struck audience; he is one of them, a man speaking to man who quietly makes his way into their hearts. If Iqbal is like Milton, Faiz is like Wordsworth in this respect.

Faiz not only acknowledged Iqbal’s greatness and wrote on him, he also helped to make a documentary on his life and work. In this context, one is reminded of a memorable observation of John Dryden. Writing of Shakespeare and Milton, he says that we admire Milton, but we love Shakespeare. One may as well say, we admire Iqbal, we love Faiz. Iqbal’s great couplet,

For ages the Narcissus bewails its purblind state

The birth of a discerning eye is an event rare and great

applies as much to Iqbal himself as it applies to Faiz.

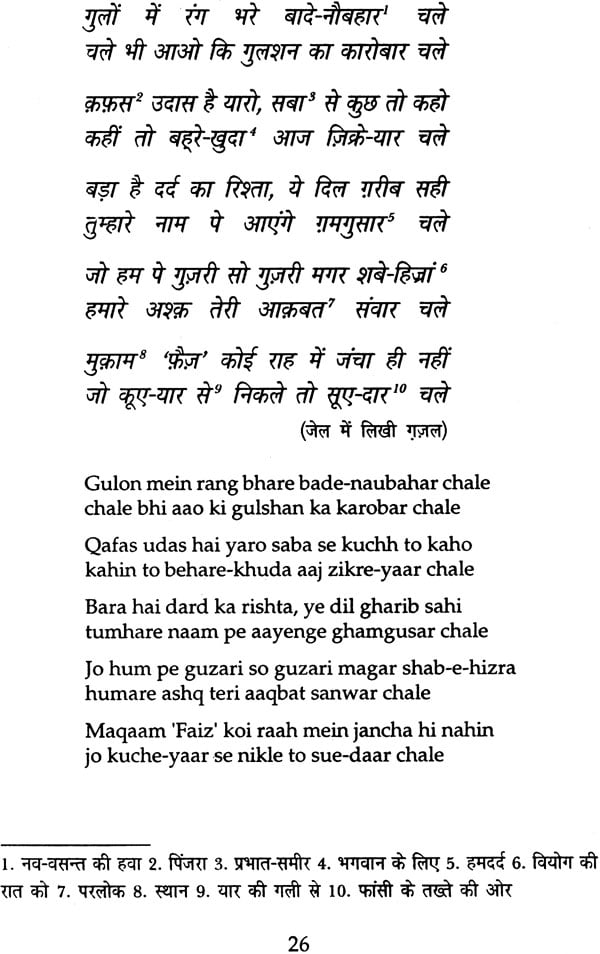

| I care not if I stand divested of the pen and the tablet | 25 |

| so thatt the flowers flush with colour, | 27 |

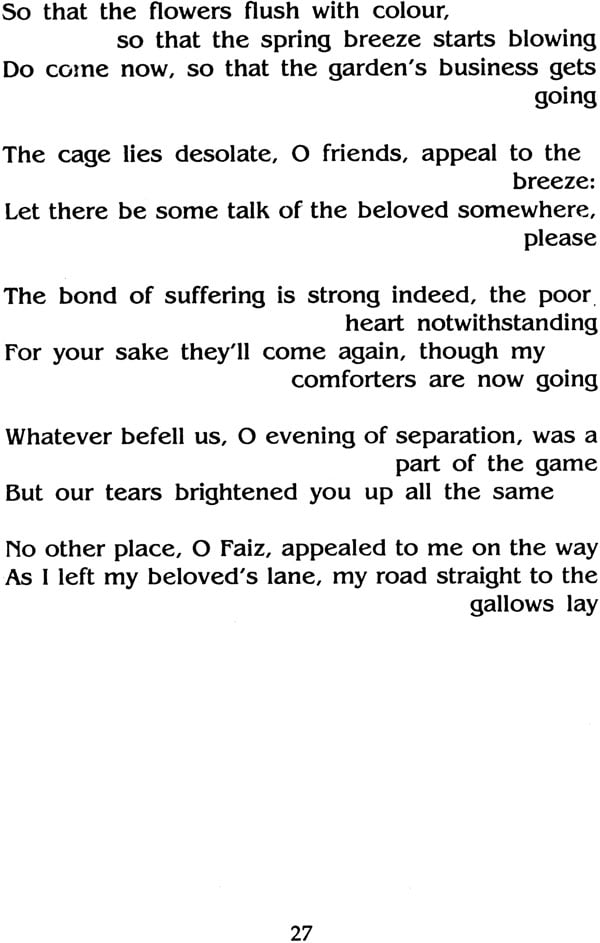

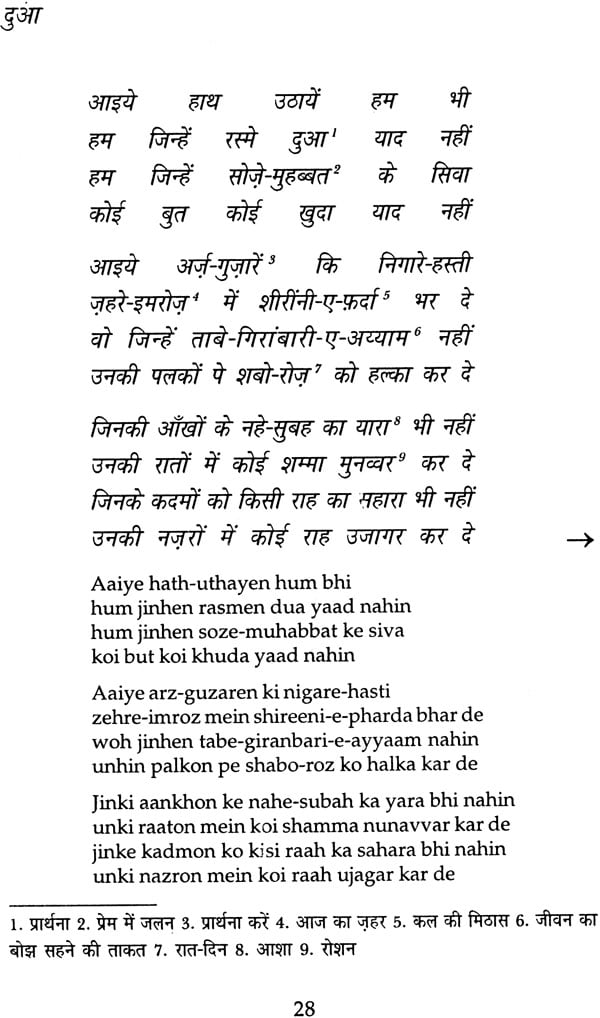

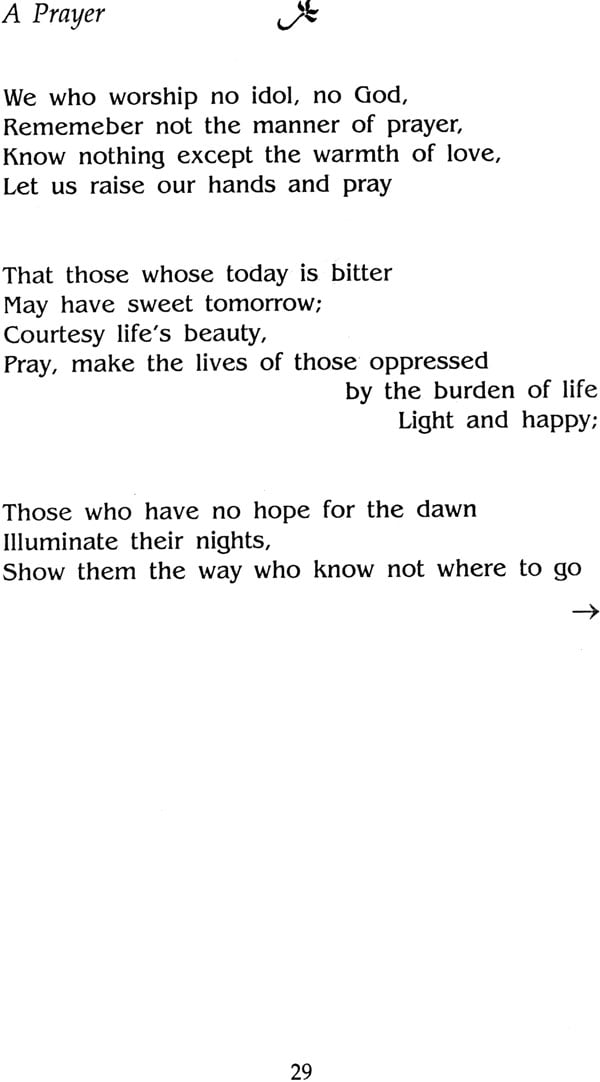

| A Prayer | 29 |

| To the Rival | 33 |

| My comrade, my Friend | 37 |

| Prison--One Evening | 41 |

| The true colour is the colour of your dress | 45 |

| Neither have you come, nor has the night of waithing passed | 47 |

| The Subject of Poetry | 49 |

| Speak up | 55 |

| To the Political Leader | 57 |

| Like a long-lost friend, loneliness this evening | 59 |

| Pain will come Soft-footed | 61 |

| Elegy | 65 |

| O ask me not how I passed the evening of separation | 67 |

| I naver made friedns Monsieur preacher | 69 |

| Ask me not forLove, O dear, like Before | 71 |

| A Few Days More, My Love | 75 |

| Two Loves | 79 |

| I will be free from worrying about gain and loss | 85 |

| Let there be some clunds, some wine | 87 |

| Loneliness | 89 |

| The Poets | 91 |

| I look for spring in the Autumn season | 95 |

| The night comes these days loke the wine, flowing | 97 |

| Let me bow befire you | 99 |

| Go to the Marketplace in Fetters Today | 103 |

| The Dawn of Freedom--August 1947 | 105 |

| Don't give me so much happiness today | 109 |

| In your love having both the workds lost | 111 |

| My Friend | 113 |

| The Evening | 115 |

| Whatever you said to us | 117 |

| Tonight | 119 |

| May God the day Never comes | 121 |

| After so many meetings we, who strangers remain | 125 |

| The last Letter | 127 |

| Tablet and the Pen | 131 |

| To your Beauty | 133 |

| the Hghway | 135 |

| My love, I have tried my very best to conceal | 137 |

| Neither do I see her, nor hear, nor is there | 139 |

| Waiting | 141 |

| Beauty and Death | 143 |

| Is it the smell of blood or fragance from | 145 |

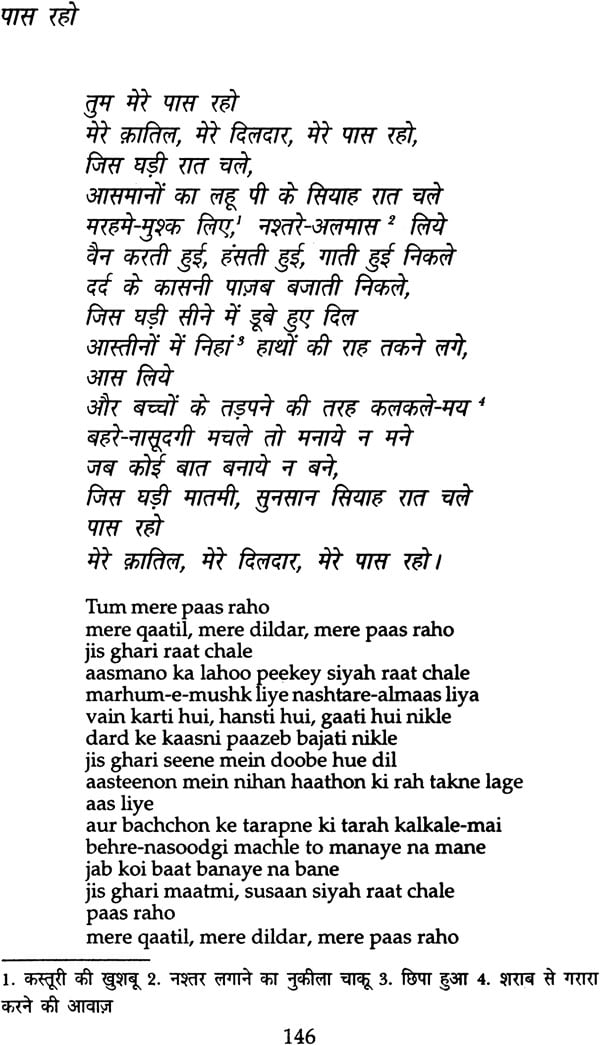

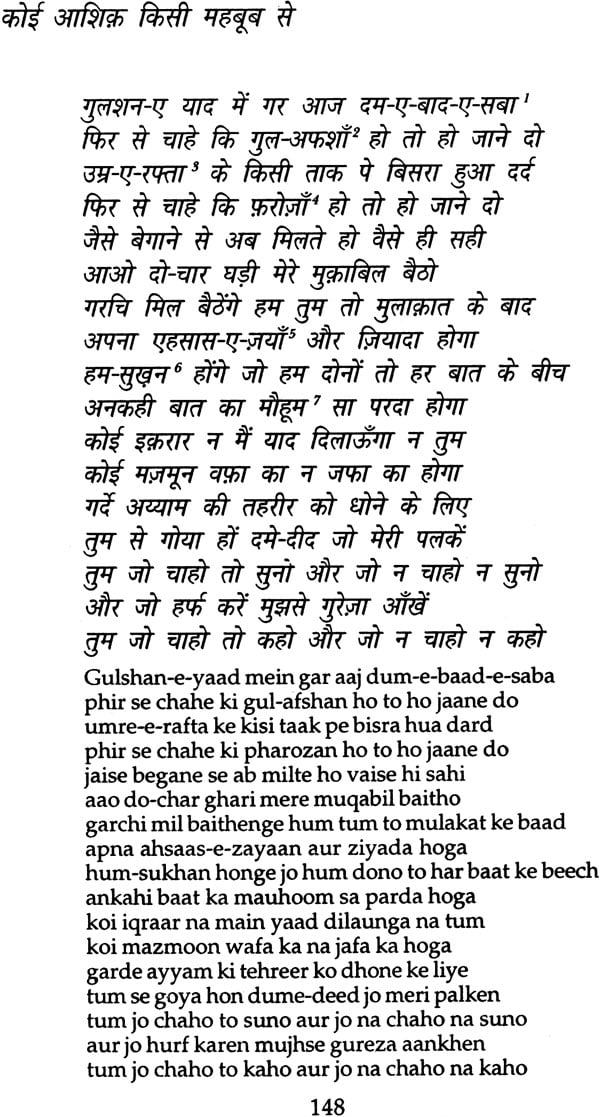

| Be near Me | 147 |

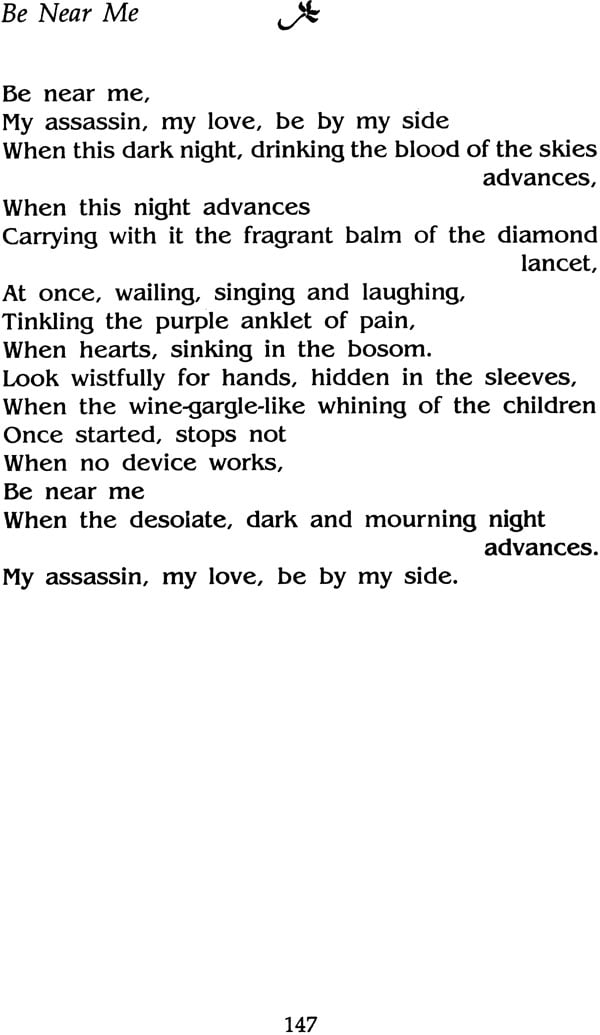

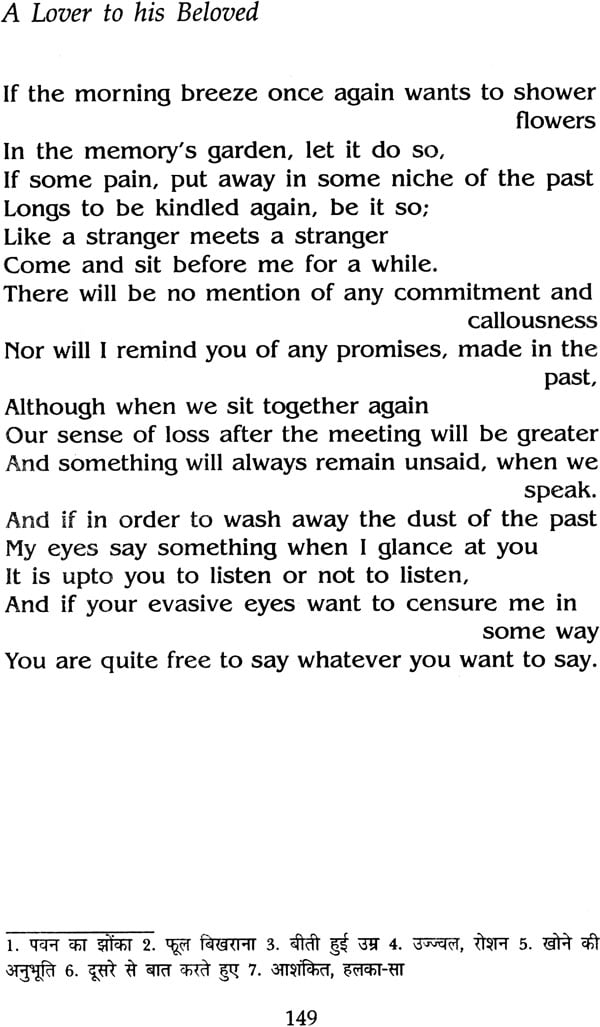

| A Love to his Beloved | 149 |

| Lullaby to the Palestenian children | 151 |

| O City of Loghts | 155 |

| My Journeyman Heart | 157 |

| Windows | 159 |

| In Your Ocean-like eyes | 161 |

| Like the arrival of spring suddenly in desolate country | 163 |

| I rise with my eyes filled with your beauty | 165 |

| Dogs | 167 |

| All night the mad heart | 169 |

| As forsaken idols, there way back ot the kaaba find | 171 |

| The same language of passion of now | 173 |