Character Reading From The Face (The Science of Physiognomy)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAL760 |

| Author: | Grace- A. Rees |

| Publisher: | Ajay Book Service |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2007 |

| ISBN: | 9788187077916 |

| Pages: | 94 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 300 gm |

Book Description

Through physiognomy you can know and improve yourself. Parents and teachers should use it for understanding and bringing up children. They can learn to understand why one child is timid and another in the same family loves to “show off "; why one child is diffident and the other destructive; why one concentrates and another will never finish a game or a task.

Alexander Walker wrote Physiognomy Founded on Physiology, and he was a writer of note on anatomical and physiological subjects. He claimed that the face was the mirror of the mind, the muscles that surround the features being, more or less, under control of the will.

Certain muscles around the nose and upper lip cause the wrinkling of the nose-skin which we do when expressing disgust, or when we detect an unpleasant smell. You will notice, too, that when the nose wrinkles the upper lip" lifts" or wrinkles involuntarily with the nose.

The muscles around the mouth are responsible for a variety of expressions, and their control of the lips is important for speech. The muscle Risorius causes the horizontal spreading of the mouth into what we call a smile. The opening and closing of the lips; mastication, wrinkling, smiling and frowning are all the by-play of muscular activity.

Our character is reflected and denoted in each feature according to how we use, abuse, or allow it to lie dormant.

Some faces have beautiful, well-balanced features but lack expression; others may be less beautiful, with irregular or rugged but expressive features. Mental capacity and sensibility enliven the face. What goes on in the mind engraves its mark externally.

The whole body is physiognomically expressive, head, face, trunk, hands, feet, walk, voice, texture of hair and skin.

Surgeons in this country and Canada who are experimenting with actions of the brain have proved that a large area of the brain controls movements of hands, eyes, lips, tongue, and even the sensitiveness and feeling of the skin surface.

There are Laws in Physiognomy, and one is that external forms vary in accordance with the differences of internal character. For example, among animals, the character, build and movements of the dray horse differ greatly from those of the racehorse; the lion differs from the deer; the leopard from the hippopotamus, the dog from the pig. This confirms the Law that configuration corresponds with organisation and function.

Throughout nature there exists an unlimited variety in the shape of living things. The differences in form and structure always correspond with the difference in character and function. The slender stalk of wheat could not support a marrow; the face of the tiger denotes its character, as does that of the lamb; the eagle is the counterpart of the dove, in external form as in behaviour.

Another Law is the Law of Homogeneousness, which states that every part corresponds with the whole, and the whole to every part. It is this principle that in olden times enabled artists and sculptors to attain harmonious proportions in their draughtsmanship. The height of the human figure should be six times the length of the human foot; the face from the top of the forehead to the chin-point should measure one- tenth of the height. The hand from the wrist to the tip of the middle finger should measure the same as the face from the edge of the hair to the bottom of the chin. If you divide the face into three equal parts, the first is from the edge of the hair on the forehead to the eyebrows, the second part to the nostrils, and the third part from the nostrils to the chin-point. Similarly, the height should equal the width to the tip of the middle fingers on each hand when the arms are extended.

Exercise increases muscular development in the size and power of certain limbs; for instance, the arm of the blacksmith. Again, the man using the pick, and the hands of certain manual workers increase in speed and dexterity through practice. The pugilist's muscles in arms, hands and legs, the legs of the ballet dancer and gymnast all confirm that the external is developed and changed by the internal.

Every motion, thought and action, according to its power and the extent of its repetition, may engrave a feature of the face-for better or for worse.

Phrenology-the study of the shape of the skull-is a close ally of Physiognomy. Many years ago Mrs. O'Dell and Miss Amy Barnard, both well-known and expert Phrenologists, convinced me of the truth and value of reading character from the head. I studied this science under Miss Barnard for a considerable time.

The chapters in this book are arranged in the right order for study and for delineating character. The student is advised to keep to this method.

Do not, at first, attempt to give verbal readings ; only attempt this when fully experienced. Write down your observations; you will find the subject whose character you are reading usually prefers it written so that he can reflect upon it.

Survey the whole face, then the profile, and decide what is the predominant temperament before beginning to record your delineation. Balance the features one against the other, mentally, and make any deductions necessary; for example, you see a weak chin but firmness in the straight, long uppper lip; or the high, wide forehead indicates that the indecision and irresolution in the slightly receding chin is counter- balanced by good logical force.

You are sure to meet with faces and features which baffle you, just as doctors find conditions and symptoms that defy diagnosis. Accept such faces as a challenge, and, if possible, discuss with the subject the feature that puzzles you.

Faces which, before you studied character-reading, seemed unattractive may afterwards become extremely interesting.

The study of Physiognomy often makes me see the best in the most ordinary faces; this is because the least likeable subject generally possesses some quality or characteristic to admire, and the reason for any frailty can usually be detected when you know how! To know all is to understand and usually to forgive all.

It is easier to discover talents, qualities and strong character, than vice. Weaknesses and vice are the result of abusing and misusing character. But vice does unmistakeably engrave the lips, mouth and eyes, - and indelibly alter the facial expression.

Smiles and frowns cause lines and wrinkles. Selfishness, meanness, ignoble thoughts and actions chisel their sad marks around certain features, just as un- selfishness, generosity, noble thoughts and ways illuminate the features and expression of the face.

Allowance must always be made where restrictive circumstances, perhaps a lack of education or training, leave some characteristic latent; for example, the sign of Tune (with which I deallater) may be prominent but the subject may never have had the opportunity for a musical training, so that the power remains dormant.

Try to read your own character! A weak chin or lack of concentration is just the same in your face as in someone else's. You may note a capacity in some feature that you are not using fully but could develop.

| ACKNOWLEDGMENTS | 5 | |

| PRELIMINARY NOTE BY THE PUBLISHER'S MEDICAL | 7 | |

| READER | ||

| INTRODUCTORY NOTE | 10 | |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | 18 | |

| I | TEMPERAMENTS CLASSIFIED | 21 |

| II | THE FOREHEAD AND EAR POSITION | 29 |

| III | THE NOSE | 36 |

| IV | THE EYES, EYE-BROWS AND EYE-LIDS | 46 |

| V | THE MOUTH AND LIPS | 52 |

| VI | THE CHIN, JAW AND EARS | 59 |

| VII | LINES AND WRINKLES | 65 |

| VII | MISCELLANEOUS POINTS | 67 |

| IX | ABOUT HANDS | 70 |

| X | ABOUT HAIR | 72 |

| XI | FOUNDERS OF PHYSIOGNOMY | 74 |

| XII | THE MODEL FACE WITH KE | 76 |

| XIII | SUMMARY OF CHARACTERISTICS OF EACH FEATURE | 81 |

| XIV | EXPLANATION OF TECHNICAL TERMS, AND | 87 |

| HOW TO MEMORISE RULES | ||

| CONCLUSION | 90 | |

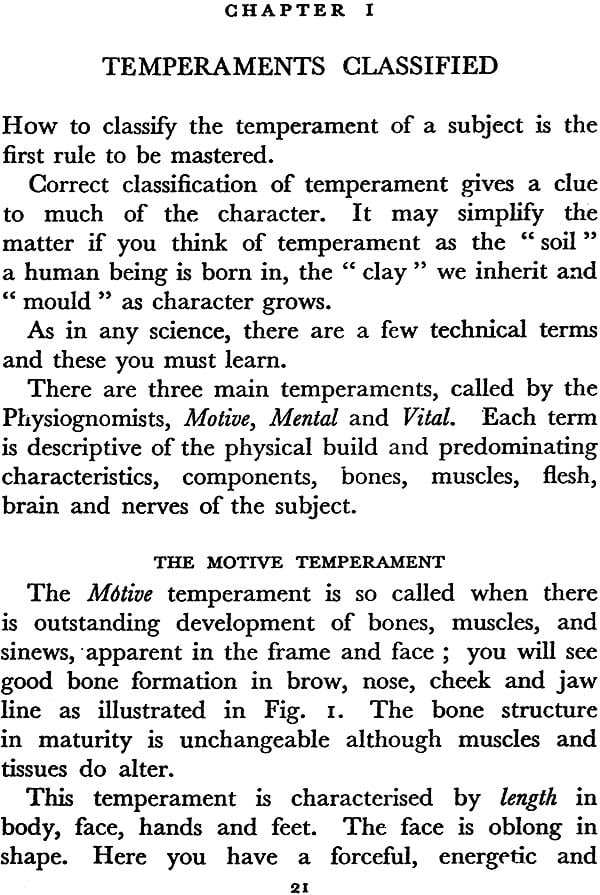

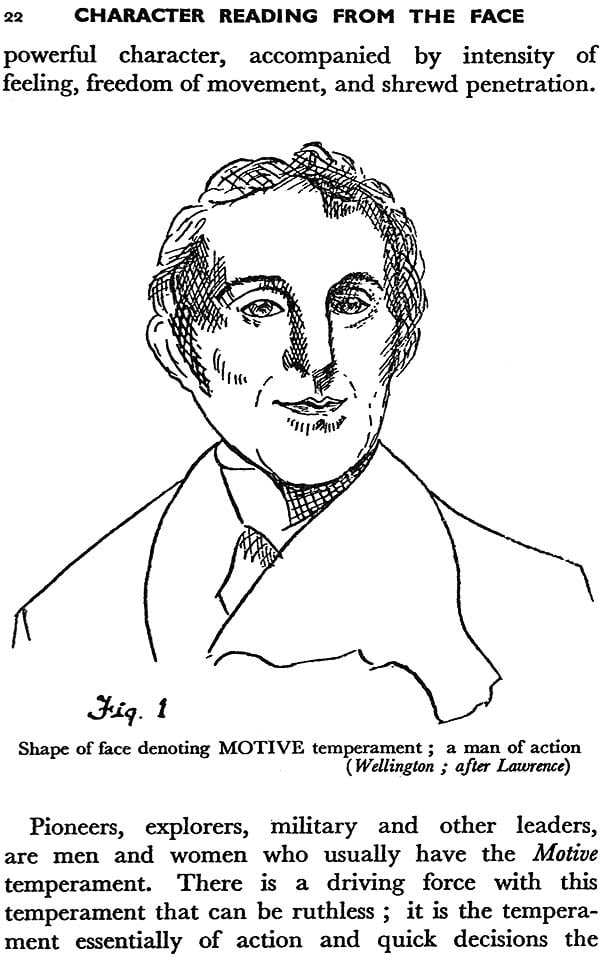

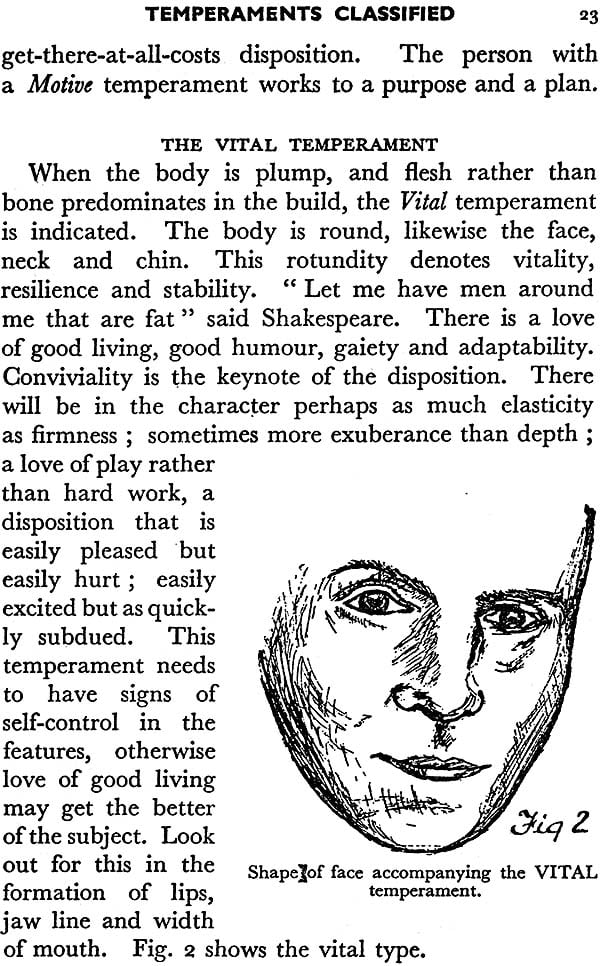

| INDEX | 91 |