Devotional Songs of Narsi Mehta

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDE749 |

| Author: | Translated By: Swami Mahadevananda |

| Publisher: | Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1995 |

| ISBN: | 8120805097 |

| Pages: | 146 (B & W Illus: 8) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.8" X 5.7" |

| Weight | 350 gm |

Book Description

From the Jacket:

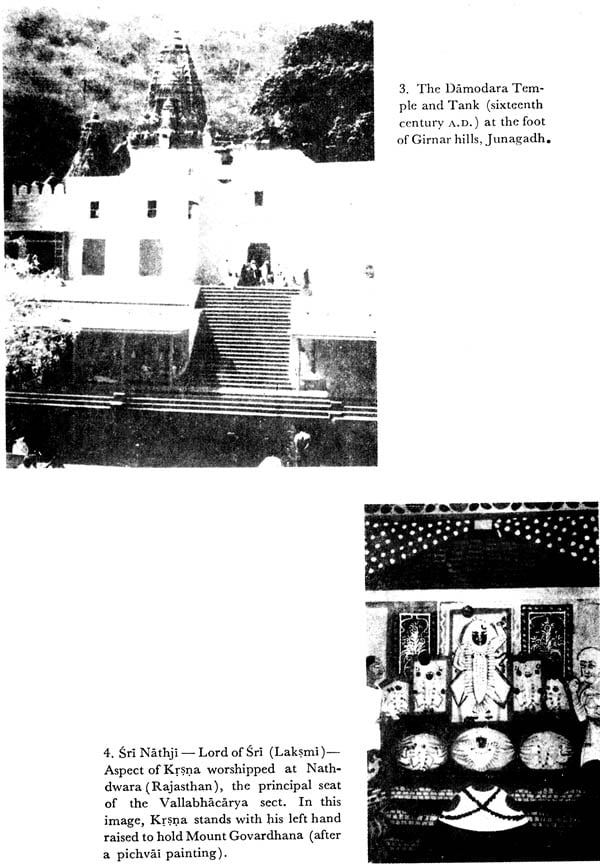

Considered to be the foremost poet-saint of Gujarat, Narsi Mehta's (A.D. 1414-1480) songs (padas) are full of devotion for Lord Krsna. They describe in a most vivid and passionate manner the early life of Krsna, his love-play with the gopis of Gokula and the basic philosophy of early bhakti cult. Narsi Mehta's style is both simple and move, and consequently the impact of his songs can still be felt in the villages of Saurashtra (Gujarat) where they have become part of the folk tradition.

Besides being a poet, devotee and saint, Narsi Mehta's was also a social reformer. Though born as an orthodox Nagar Brahmin, he was one of the strongest critics of the caste system and its evils. His naturally sensitive and loving nature revolted against the treatment of untouchables by his castemen. Narsi knew no caste distinctions; he looked upon all human beings as the children of Hari (Harijana).

A hundred songs, representative of Narsi Mehta's philosophy, social message and the portrayal of love-play between Radha and Krsna (Radha-Krsna lila) are for the first time translated into simple and direct English verse.

About the Author:

Swami Mahadevananda (Roger Timms) was born in England. He gradutated as a fully trained actor from the Central School of Speech and Drama, London. After several years as an actor on the British stage, he came to India to study Indian traditional dance and drama. This led to his interest in Indian philosophy and religion and he later took sannyasa from Rishikesh. Recently he has been running a drama school for children, called KINARA (Kiriyara Nataka Ranga) in Mysore.

Sivapriyananda, who has written the introduction, was born into a royal family of a princely state in Gujarat. He studied Sanskrit and Pali at the Poona University and for the Kavyatirtha of the Bengal Sanskrit Association, Calcutta. He also did his post-graduate studies in archaeology at the London University. At present, he divides his time between writing and farming.

Excerpts from Reviews:

A wonderfully readable book, it leaves a vivid impression of undying love, sublime and cosmic, expressed with the naivete of true goodness.

Narsi Mehta was born at a time when Muslim rule had been firmly established in Gujarat. In A.D. 1411, Ahmedabad had be- come the capital of Ahmed Shah I, the third Sultan of Gujarat. Frequent Muslim raids into Saurashtra had disturbed its social and political stability. Traditional Hindu society was being shak- en at its very roots. In literature, the influence of Sanskrit court poetry had almost disappeared. Even Jainism, which had been the main creative force in the-literature of Gujarat for more than five centuries, was fighting a losing battle for survival against the new folk literature which was. becoming very popular under the influence of the cult of bhakti.

The word 'bhakti' comes from the Sanskrit root bhaj which means 'to serve', 'to adore' and 'to honour'. In the religious sense it refers to the doctrine of adoration for a personalized God (istadevata ). The idea of bhakti was not new to Hinduism. It was mentioned in the Svetasvatara Upanisad (c. 500 B.C.) and later very clearly expounded in the Bhagavad-gita (c. 300 B.C.) by Krsna himself. The most complete glorification of the bhakti doctrine was given in the Bhagavata Purana (between A.D. 500 and A.D. 900), a text which is still considered to be the greatest single sourcebook of bhakti and the mythology of Krsna.

The philosophical nature of bhakti was defined by Narada and Sandilya (both c. A.D. 900) in their respective Bhaktisutras as 'supreme love for God'. Many later scholars and philosophers built entire systems of philosophy on the simple, basic idea of intense devotion to a personalized God. The most important of these philosophers, whose sects still survive and have a large following, were: Ramanuja (born A.D. 1021), Nimbarka (born A.D. 1130),Madhva (born A.D. 1197), Visnusvamin (fourteenth century A.D.) and his follower Vallabhacarya (A.D. 1478-1530).

The medieval revival of the path of bhakti was, however, only indirectly based on the works of the great scholars and philo- sophers. Its real inspiration came from the strongly emotional hymns, of very great literary merit, composed in the language of the people by early Tamil saints: the Vaisnava Alvars and the Saiva Nayanars (from A.D. 300-800). By the thirteenth century A.D., the cult of bhakti and the tradition of composing emotion- ally charged devotional songs in the spoken languages spread from the Tamil-speaking areas to Karnataka and Maharashtra. A Sanskrit verse that is often quoted in the early Puranas says:

Bhakti was born in the Dravida country, developed and flour- ished in Karnataka, had some success in Maharashtra, but dis- appeared when it reached Gujarat.

The most important feature of the bhakti cult was the great stress it laid on sincere and intense devotion to a personal, all- loving and gracious God. The purity of personal character was stressed instead of caste status, and empty rites and ceremonials were worthless when compared to a loving heart. All caste dis- tinctions were abandoned, and the path of bhakti was open to the high-born Brahmins as well as to the lowest of the untouch- ables. Quite a number of the bhaktas were actually members of the lower castes of Hindu society.

The bhaktas preached that there was no need to use the com- plicated philosophical process of reasoning in order to understand the divine, Deep love of God, the constant repetition of his names, and the steady company of other devotees was enough to bring God's grace and to reach everlasting union with the divine.

Though orthodox ceremonials were shunned, nine well-defined aids to bhakti were recongnized. These helped the devotee to establish a personal and intimate relationship with the desired form of the deity. The nine are, according to the Bhagavata Purana (VII, 5, 23): hearing (sravana) and singing (kirtana) the praise of the Lord; remembering (smarana) his names at all times; serving (padasevana ) I worshipping (arcana) and bow- ing low (vandana ) to his lotus feet; complete servitude (dasya), a strong and intimate relationship (sakhya) and absolute sur- render (atma-nivedana) to the Lord.

There wore never any restrictions regarding the deity to which a bhakta's devotion was to be directed. A strong, sincere, and steadfast devotion to any deity, or for that matter even to the formless Brahman of the Upanisads, could bring about the same spiritual results. But in spite of this rather catholic freedom to devote oneself to any deity, most medieval saint-poets dedicated themselves to the two most popular incarnations of Visnu in the form of Rama and Krsna: Rama as the embodiment of right- eousness and absolute truth; and Krsna as the personification of love and the divine joy that destroys all pain.

The emotion of bhakti [bhakti-bhava) can take-many forms, depending upon the psychological nature of the devotee. The bhakta may take the emotional attitude of a servant to his master (dasya); or of one friend to another (sakhya) ; or of a parent to a child (Vatsalya); or of a child to a parent (santa); or of a wife to her husband (kinta); or of a beloved to her lover (rati or madhurya); or of a god-hater towards god (dvesa). In fact, it did not matter in the least ,what the individual's emotional feeling was towards god, as long as there was an overpowering, unshakable, emotional intimacy. Ravana, the evil king of Lanka in the Ramayana epic, hated Rama so much that he constantly remembered him. Through his hatred he attained salvation.

Another chief distinguishing feature of the medieval bhakti marga was that almost all its exponents composed and recited songs and poems, full of the most fervent devotion, in the Iangu- age of the people. They discarded the use of the traditionally sanctified religious language Sanskrit, so that more and more people could understand the basic doctrine of devotion to a per- sonal, living, humane God; and this led to the rapid and wide- spread popularity of the cult of bhakti.

The greatest, and perhaps the most significant bhakta-poet of Gujarat was Narsi Mehta. He belonged to the very rigidly ortho- dox and prosperous caste of Nagar Brahmins of Vagnagar (near Mehsana in north Gujarat). Unlike the life of many medieval bhakta-poets, the life-events of Narsi Mehta are well recorded. Though later accounts have added many legends and tales des- cribing miracles, the basic facts of his biography are quite easy to reconstruct.

The poet himself has left us three complete au tobiographical works: Samalsa no vivah (marriage of son Samalsa) , Kunvarbai nu mamerun (incidents relating to the gifts given by Narsi Mehta to his daughter Kunvarbai in the seventh month of her first preg- nancy), and Har-mala (garland incident). Besides these three works, there are numerous verses on isolated events in his life. Many later Gujarati poets, in particular Visvanath Jani (c. A.D. 1652) and Premanand (A.D. 1636-1734) ,have written long poems describing the life of Narsi. By the seventeenth century A.D., primarily on account of Jani's works, Narsi Mehta's fame had spread well beyond the borders of Gujarat to be included in Na- bhaji's (A.D. 1634-55) famous Bhakta mala (garland of devotees) , an account of Vaisnava saints.

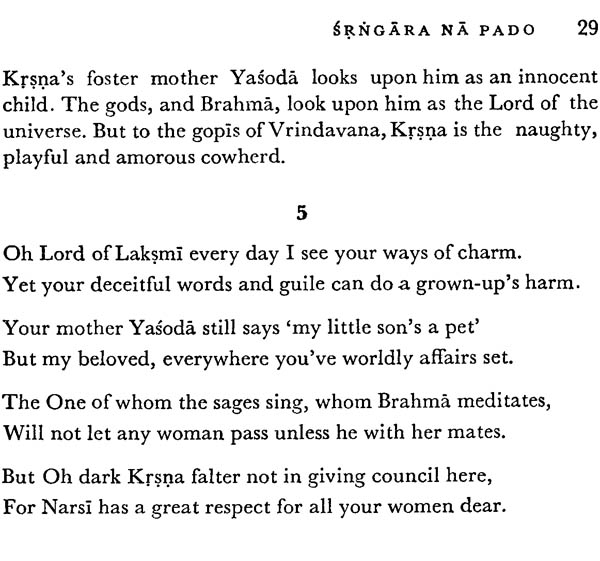

Narsi Mehta's grandfather, Visnudas worked as the head clerk in the court of the devout Vaisnava ruler Ra Muktasinh (A.D.1373-97)of Junagadh. After Visnudas' death, Narsi's father Krsnadas was unemployed for a long time and so returned to Talaja, a small town about 30 kilometers south of modem Bhavnagar, where the family probably had an ancestral house. Krsnadas had had two sons and a daughter before Narsi's birth, but they had all died in childhood.

Narsi was 'born at Talaja when his father was quite an old man. According to the traditionally accepted date, Narsi was born on the second day of the bright half of the lunar month of Margasirsa (November-December) in the Vikrama-samvat (s.) year 1470 (A.D. 1414).2 Most modem scholars accepts this tra- ditional date. The. only scholar to raise any serious doubt was K. M. Munshi, who tried to place Narsi's birth sometime between s. 1530 (A.D. 1474) and s. 1580 (A.D. 1522). His arguments have found very little support. .

Krsnadas died in S. 1473 (A.D. 1417) when Narsiwas only three years old. After his father's death, Narsi and his mother Dayakor went to live with Parvatdas, Narsi's paternal uncle. It is not cer- tain as to where Parvatdas actually lived. Tradition says he lived in Talaja; Visvanath Jani says he lived in Junagadh; and Vallabhadas says he lived in Mangrol, a small coastal town south- west of Junagadh.

A popular legend tells us that the child Narsi could not speak. At the age of eight, he started speaking after being blessed by a wandering Vaisnava monk. Some say that this wandering monk was no other than the great south Indian scholar, philosopher and founder of the Rudra sampradaya, Visnusvamin, There is, however, no historical evidence for this legend.

If we follow the traditional account of Narsi's early life, his childhood was spent in Talaja. He probably went to the local school with his cousins.where he learnt the Gujarati language of his day, and perhaps a little Sanskrit. His religious education was done at home by his mother and uncle Parvatdas who were both devout Vaisnavas, They must have certainly taught him the basic philosophy of their sect and the Visnu-Krsna mythology from the Bhagavata and other Puranas. At the early age of eleven, according to custom, Narsi was engaged to be married to the daughter of a wealthy Nagar gentleman. But the engagement was broken off when it was discovered that Narsi was no good at studies, and that he spent most of his time either with wandering mendicants or sitting alone in little caves. A small cell in the complex of second century A.D. Buddhist caves in the hill near Talaja is still identified as the 'school' of Narsi Mehta. Most of Narsi's co-students considered him to be rather odd and abnormal as he frequently dressed himself up in the women's clothes and danced in front of the religious mendicants.

| Bulletin of the Ramakrishna Mission, Institute of Calcutta, Vol. XXXVIII No. 4, April 1987 | Malosree Chaudhuri |

Here is a rich fare of 100 select devotional songs of the great poet saint Narsi Mehta The scholarly Introduction of Madhavanandaji gives us an account of the saint's life and his works, and the traditional religious background of the songs The Publisher is to be complimented on the very fine way the book has been produced.

| The Quarterly Journal of the Mystic Society, July-Sept. 1986 | S.V. Desika Char |

There is a splendid introduction to the book by Sivapriyananda who gives an excellent and elaborate biographical sketch of Narsi Mehta's life, personal and public, and devotional life Translations is simply superb, free-flowing and words are highly musical and pleasing.

| The Vedanta Kesari | Prof. N. Sankaran |

The explanatory notes are very helpful in explaining the esoteric significance of many of the passages. A book that purifies.

| The Mountain Path, Oct. 1985 | M.P. Pandit |

The translation is both faithful and readable. A bibliography and index add to the usefulness of this well-brought out volume.

| The Adyar Library Bulletin | K.K. Raja |

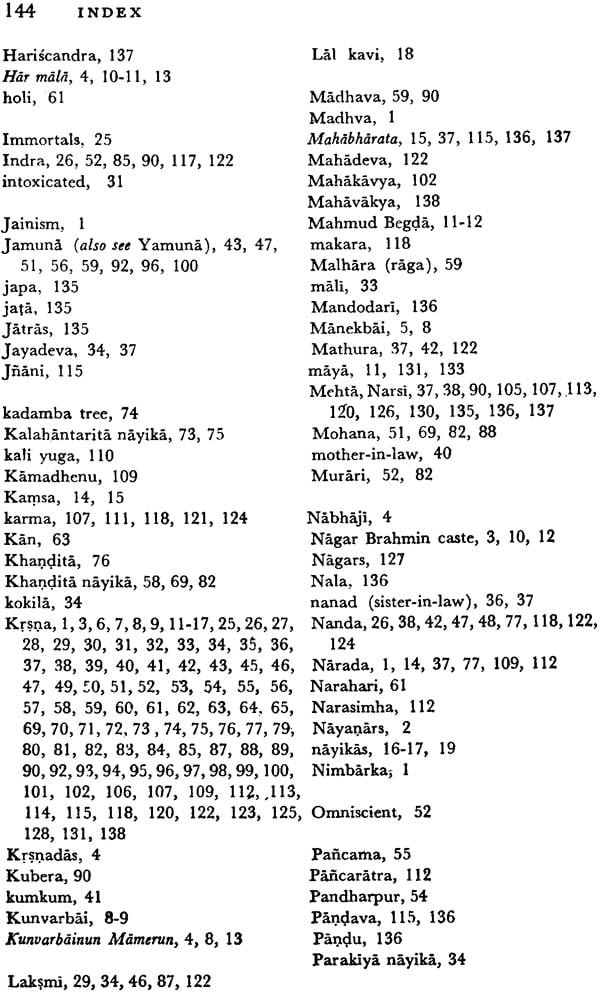

| Introduction | 1 |

| Translator's Note | 21 |

| SRNGARA NA PADO [1-40] | 23 |

| SRNGARA MALA [41-70] | 67 |

| BHAKTI, JNANA ANE VAIRAGYA NA PADO [71-100] | 103 |

| Bibliography | 141 |

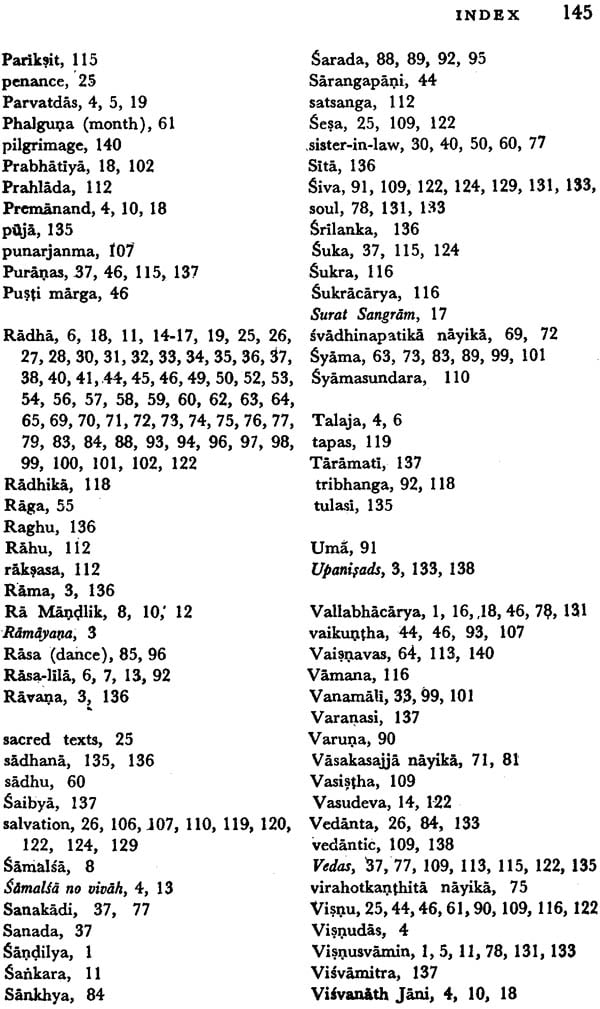

| Index | 143 |

Click Here For More Books on the Pali Language