Diwan-e-Ghalib (Poetries by Ghalib)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAV215 |

| Author: | Kuldip Salil |

| Publisher: | Rajpal and Sons |

| Language: | English and Hindi |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 9788170286929 |

| Pages: | 142 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 250 gm |

Book Description

"With Meer, Ghalib, Iqbal and Faiz, to name only four, the firmament of Urdu poetry is truly star-studded, with numerous starlets strewn around. Ghalib has not only pride of place among them but his stature is growing with every passing decade. He was ahead of his time, and his contemporaries failed to comprehend him fully. It was when India (and Pakistan) celebrated his first death centenary in 1969 that Ghalib was really rehabilitated and recognised as the great poet that he is. There has been no looking back after that.

As with other great poets like Shakespeare, one discovers a new wealth of meaning every time one reads him, and different people find different meaning, suiting their need and situation. In other words, great poets are inexhaustible in their appeal and meaning and do not get dated even when they mirror their times most effectively. Ghalib’s writings are not only an authentic account of this own age, his poetry transcends his times and situation and is universal in its appeal."

Mirza Asad-Ullah Khan Ghalib is the greatest Urdu poet, and one of the greatest in any Indian language. He could rank perhaps among the great poets of the world. There is an interesting parallel between Meer Taqi Meer and Mirza Ghalib on the one hand, and William Shakespeare and John Milton on the other. Shakespeare died in 1616 when Milton was eight years old. Ghalib was about Milton’s age when Meer, who was then in his last days, read some of Ghalib’s writings, which were taken to him by an early admirer of Ghalib. And if Shakespeare and Milton are the greatest English poets, Meer and Ghalib are the greatest in Urdu. There is one difference though—in English it is the senior poet who is the greatest, in Urdu it is the junior. With Meer, Ghalib, Iqbal and Faiz, to name only four, the firmament of Urdu poetry is truly star-studded, with numerous starlets strewn around. Ghalib has not only a pride of place among them; his stature is growing with every passing decade. He got less than his due in his own time. He was ahead of his age, and his contemporaries failed to comprehend him fully. Then he was pilloried on conventional moral grounds. Add to these his difficult language and subtlety of thought. As a result, his reputation as a poet suffered not only in his own day, but for decades after his death. In this respect, his friend and disciple, Altaf Hussain Hali with his ‘ Yadgar-e-Ghalib’ rendered yeoman’s service in establishing him. Others too saw his merit as a poet, but it was really when India (and Pakistan) celebrated his first death centenary in 1969 that he was rehabilitated as a great poet that he is. There has been no looking back after that. As with other great poets like Shakespeare, one discovers a new wealth of meaning every time one reads him, and different people find different meaning, suiting their need and situation. In other words, great poets are inexhaustible in their appeal and meaning and do not get dated even when they mirror their times most effectively. Ghalib’s writings are not only an authentic account of his own age, his poetry transcends his times and situation. It is universal in its appeal.

Ghalib is truly a modern poet. Modern age is characterised by doubt and scepticism, irony and satire, suggestiveness and understatement, a rational outlook (at least professedly), a result oriented scientific attitude and secularism. When asked by Sir Sayyed Ahmed Khan to write a preface to his edited version of ‘Aaeen-e-Akbari’, Ghalib wrote it in verse, praising Sir Sayyed in the beginning but lambasting him for his efforts to flog a dead horse, pointing out that rather than eulogising Akbar’s administration, one would do well to learn from modern scientific inventions and works being undertaken by the British— things like steam-ships, railways, telegraph—and their stream- lined administration and discipline. His dictum was—murda parvardan mubarak kaar-neest—(there 1s no credit in praising the dead ideals.)

Sir Sayyed felt so annoyed that he did not use Ghalib’s preface.

One of the factors in Ghalib’s greatness is his ability to detach himself from himself. He was afflicted by a whole lot of troubles, his life was a veritable tale of woe, and yet, he is able to laugh at himself. He was jailed for defaulting on payment to the moneylender. After his release, Ghalib agreed to stay at one Kale Sahib’s house. Says he, "Which bastard says that I have been released from jail? Earlier I was in white man’s jail, now I am in black man’s custody." When a friend paid the fine for the default on payment because Ghalib was in no position to pay, the poet writes.

We drank on credit, but always knew that our recklessness will one day a mischief do Ghalib separates himself from his suffering, looks at them bemused from a distance, brings out their poignancy, presents them most effectively—and jokes about them. He can speak about his humiliations, his misdeeds, his sorrows most objectively as if they were not his own but those of somebody else. And this perhaps makes them bearable:

Ghalib would be torn to pieces, the news was hot We too went to witness the fun, but it was not He can cast a cold glance at his own situation, be merciless and lambast himself:

How could you have, the cheek, Ghalib to do, a pilgrimage to Kaba But shame is perhaps the last thing to have touched you An outstanding feature of Ghalib’s poetry and prose is his wit and humour, often at his own cost:

You are his liege Ghalib, so bless the king Gone are the days when you could say you ‘re not serving Wit, humour, irony and satire sum up the sunny side of Ghalib’s personality. When somebody said that if he continued drinking, his prayers will not be granted by God, Ghalib retorted that if somebody gets wine to drink, what does he need to pray for. He was a courteous man. Once he carried a candle to help a friend find his shoes. When the friend protested, Ghalib replied that he was doing so to make sure that "you do not take away my shoes." And his famous jibe on Zauq, apparently at his own cost, can amuse us forever and ever.

But a kings courtier he struts up and down Otherwise who cares for Ghalib in the town This wit and humour is a strong shield against sufferings.

In fact a sturdiness of mind, even a stubbornness in the face of sufferings that emerges from his writings is a great thing about Ghalib. It is noteworthy that misfortunes cannot crush his spirits. His zest, even lust for life is unlimited.

Although Ghalib has been a part of my growing up from early boyhood, the idea of translating him is not more than a year old. I must confess that when the suggestion first came from a friend, I had serious trepidation. But once I started the work I experienced little difficulty. In fact, I took more time in writing the ‘Introduction’ than in translating the ghazals. This was perhaps because I have been for many years now translating poetry from Hindi and Urdu into English and vice-versa, my first translation work being Shamsher Bahadur Singh’s Sahitya Academy award- winning collection of poems from Hindi into English. A col- lection of my translation of some of the best-known English poems from Shakespeare to W.H. Auden was published two years back.

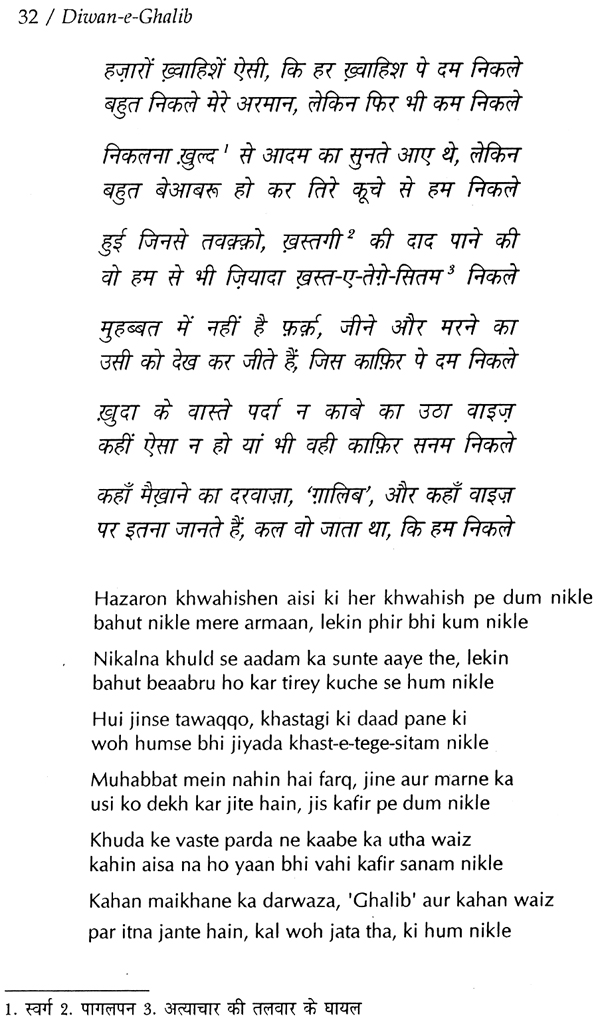

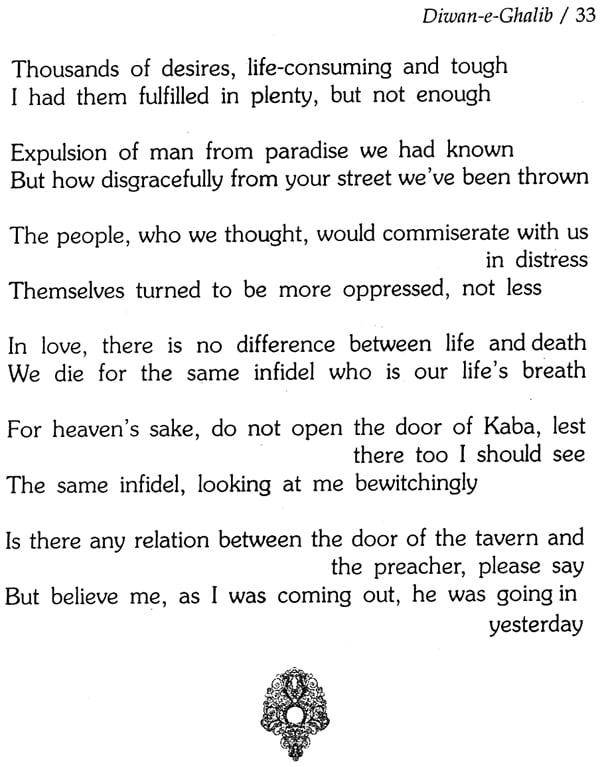

Translating Ghalib was, however a different proposition al- together. For one thing, translating a ghazal into English and still retaining its charm and appeal is, indeed, difficult. And in the case of Ghalib, this difficulty is even greater. It is relatively easy to give prose translation of a ghazal. It may serve some purpose but conveys little of the charm and beauty of the original. In fact, it is well-nigh impossible to do full justice to poetry, particularly the ghazal in translation. The best I thought that could be done was to translate the verses into independent rhymed couplets. Also, I have tried to be faithful to the original. I have not attempted to translate the entire Diwan-e-Ghalib; I couldn’t have. It is only a selection from the Urdu Diwan.

In my assessment of Ghalib’s poetry in the ‘Introduction’, I have given some of its traits that I have long thought make him a great poet. I have also given illustrations from the text.

In writing about the life and times of the poet, I have drawn on many sources. Among them are the works of Quratulain Hyder, Ijaz Ahmed, Ralph Russel, Pavan Varma and Sardar Jafri. I express my gratitude to these learned authors. I would, in this regard, acknowledge my debt particularly to Ralph Russel. I have greatly benefitted from his scholarly work. Hali’s ‘ Yadgar-e-Ghalib’ has of course been a primary source.

I would like to express my thanks to Dr. Khalid Ashraf of the Department of Urdu, Kirori Mal College and to Dr. S.R. Singh, Dr. C.D. Verma, Professor S.N. Sharma, Professor K.G. Verma and Mithuraaj Dhusiya at the department of English of Delhi University and Mr. O.P. Sapra for their valuable help and suggestions, and for reading through the manuscript. Dr. Khalid, in fact, settled for me the meaning of some of the controversial verses. Thanks are also due to my daughters Ritu and Sarika for their help in preparing the manuscript. I express my thanks also to Shri Vishv Nath who suggested the project to me and encouraged me at every step.

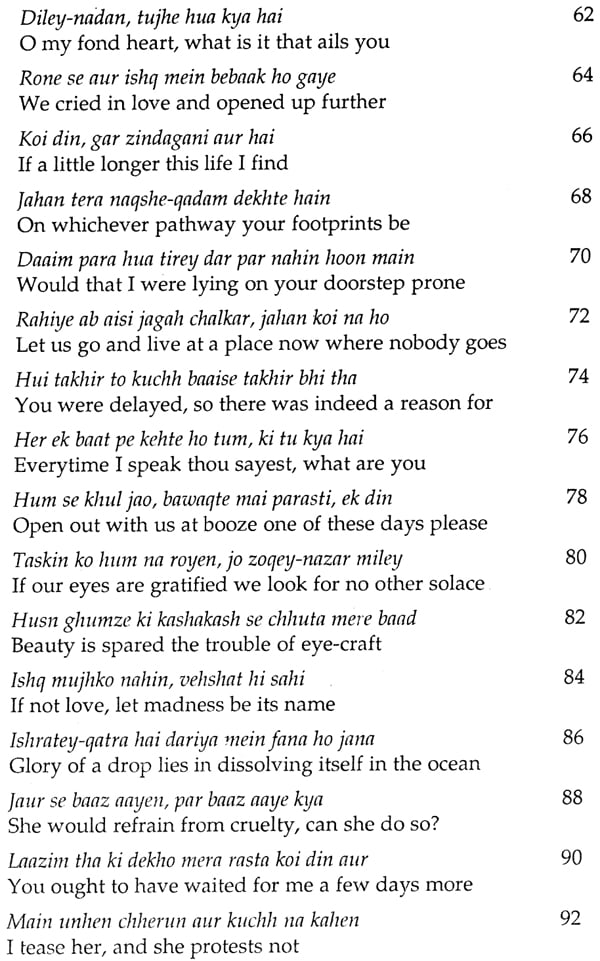

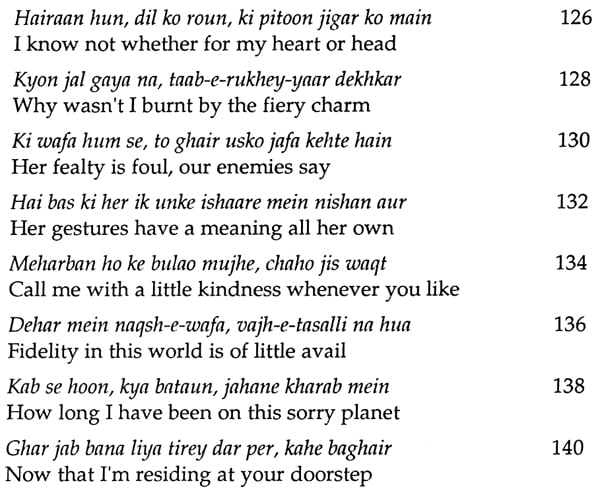

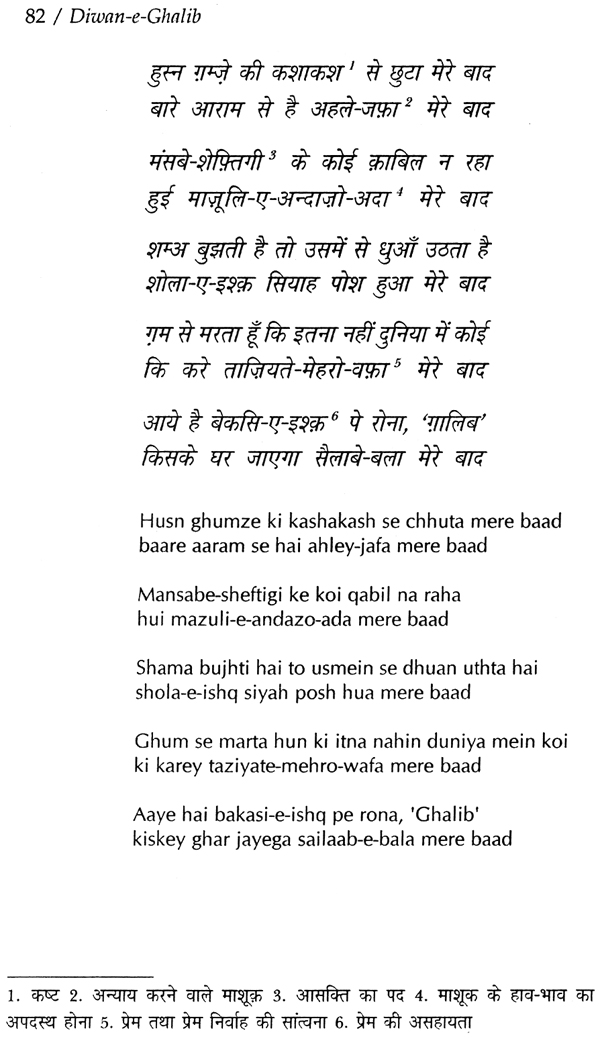

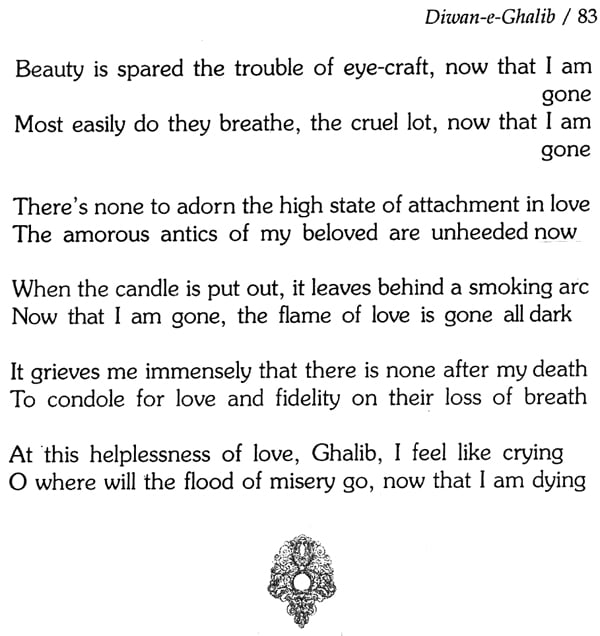

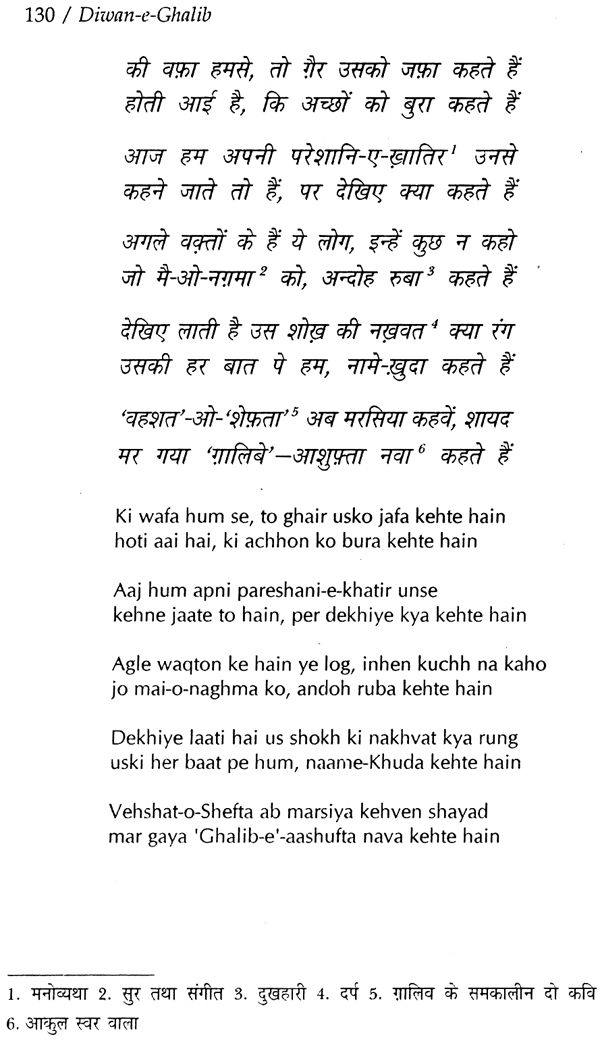

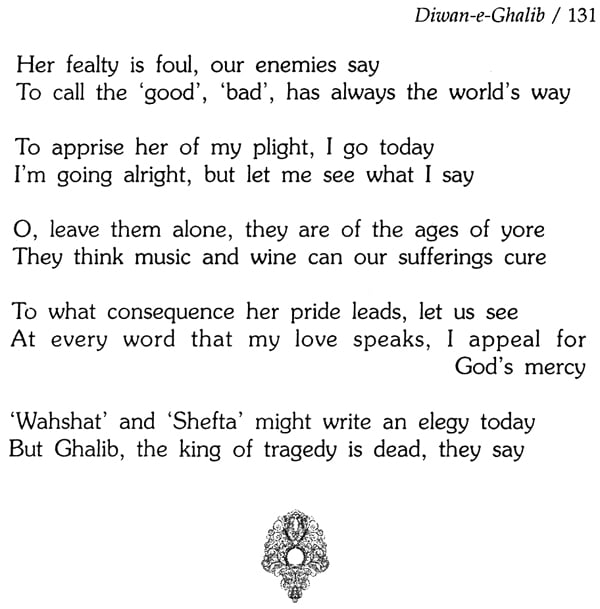

**Contents and Sample Pages**