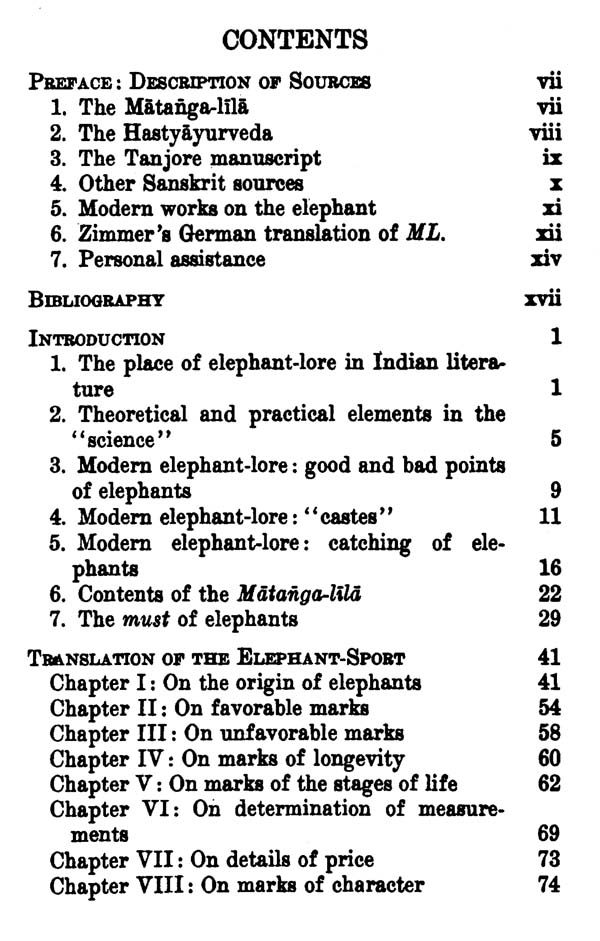

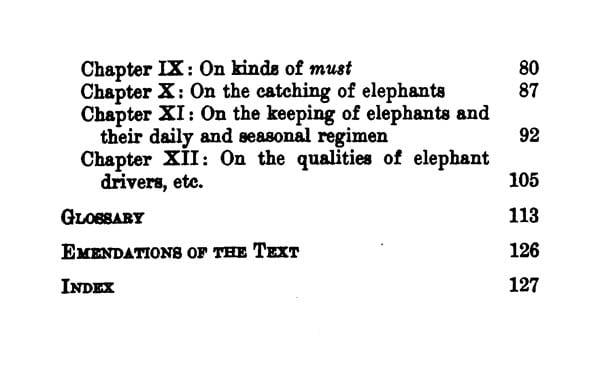

The Elephant-Lore Of The Hindus : The Elephant-sport (Matanga-Lila) Of Nilakantha (Translated From The Original Sanskrit With Introduction, Notes, and Glossary)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAX025 |

| Author: | Franklin Edgerton |

| Publisher: | MOTILAL BANARSI DASS CHENNAI |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1985 |

| ISBN: | 9788120800052 |

| Pages: | 129 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 170 gm |

Book Description

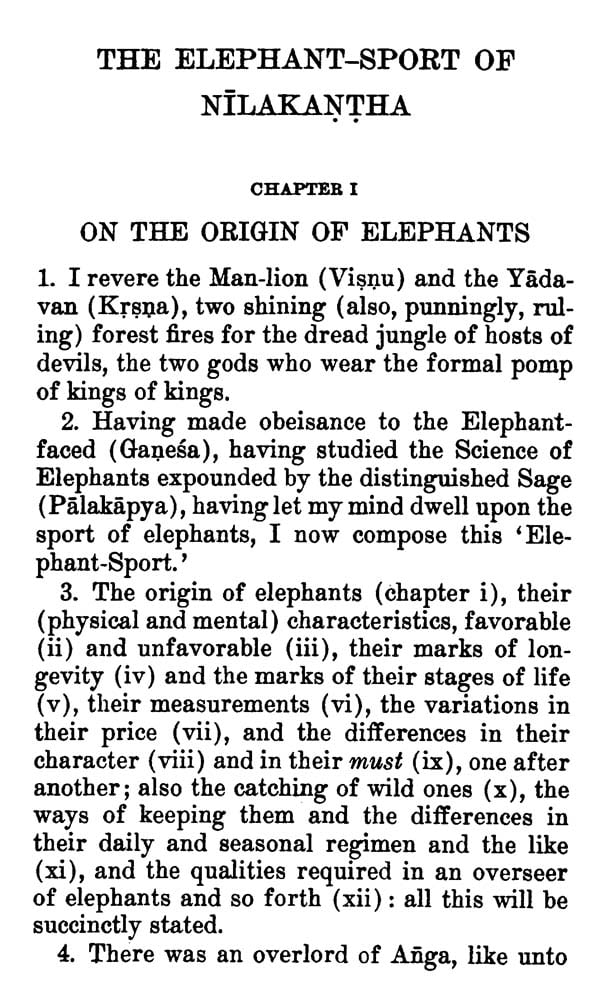

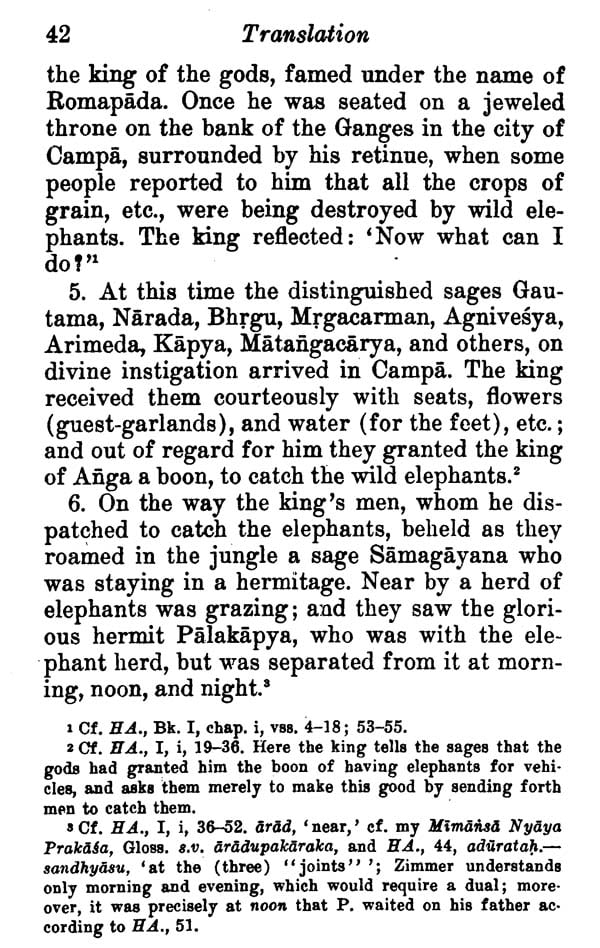

1.Tha MATANGA-LILA This book is intended to serve as an introduction to the elephant-lore of the Hindus. It consists primarily of a translation of the "Elephant-Sport" (Matanga-lila, abbreviated ML.; see the, Bibliography for bibliographical data on this and other works here mentioned) of Nilakantha, with notes, introduction, and glossary. The ML. is without doubt the best available Sanskrit work on elephantology. It is a brief and succinct treatise in 263 stanzas, divided into twelve chapters of uneven length (ranging from only three stanzas up to fifty-one). Nothing is known of the Nilakantha who is mentioned as its author, nor is there any evidence as to its date. According to the editor, Ganapati Sastri, the three manuscripts he used are about two hundred years old. But the work is probably very much older. For aught we know it may go back a thousand years, or even to a much earlier date. This, however; is purely conjectural; all we can say is that there is no positive trace of modernity in the work. Ganapati Sastri says that it is very well known in Kerala (Malabar), and on this ground guesses that its author may have been a native of this region ; naturally, this is no very strong argument.

The author was a competent pandit ; his Sanskrit is in the main good. His meters are elaborate and varied, including most of the better-known varieties of classical chandas; only a few verses are composed in the commonplace sloka. In general they are well constructed; but there are a few faulty verses, such as xi, 43, where the first pada ends in the middle of the word asa-tmya. The style is highly condensed, so much so that it is hard to understand at times. Sometimes it is almost sutra-like in hinting at, rather than explaining, its subject matter. (See, e.g., viii, 16, with my note 73.) Not a few verses would have remained obscure, or at least doubtful, to me without the aid of parallel passages; and there remain a few in which, for lack of such parallels, I fear I may not have been entirely successful. It should be added that, as the editor says, his manuscripts were "not free from errors." I have made a dozen emendations in the text as edited, all of which I consider virtually certain ; and I suspect textual corruptions in a number of other places.

On the technical vocabulary of the ML., that is, the words used in it which are drawn from the special "lingo" of elephant trainers, see the first section of my Introduction.

2.THE HASTYAYURVEDA. The only other Sanskrit work on elephants which has been published, so far as I know, is the Hastyayurveda (abbreviated HA.). As the name implies, it is primarily a work on the medical treatment of elephants, and so quite different in scope and purpose from ML. It covers, however, some of the same ground. (A brief analysis of its contents is found in Zimmer, pp. 136 ff.) The parts of the body, for instance, are listed, in very much greater detail than in ML., vi, 7 ff; also the daily and seasonal care, feeding, etc., treated in ML., chapter xi. The mythological part of ML., i, is likewise contained, at much greater length, in HA. In large part, however, HA. is obviously a secondary adaptation to elephants of the theories of Indian (human) medicine. Even the subject of must (cf. ML., ix, and my Introduction, sec. 7) is treated only perfunctorily (chiefly as depending on the various bodily "humors") in HA., ii, 61. In my notes to the Translation I have referred to parallels in HA. so far as they have a bearing on the contents of ML. ; such parallels are disappointingly few. HA. is a very diffuse and bulky work (717 pages) ; its verbosity is in striking contrast to the elegant brevity of ML. It is composed mainly in sloka meter, but with occasional prose passages of considerable length.

3. THE TANJORE MANUSCRIPT. I have had access in manuscript copy to one other Sanskrit work on elephantology, to which I refer as T. Unfortunately, the original manuscript is unique so far as known, and is both incomplete and very corrupt. In spite of this it has proved much more useful for my purpose than HA. In its complete form it probably covered the whole field of elephant-lore more fully than even ML.; the fragment we have treats of most of the contents of ML., and of some other aspects of the subject. T seems to be a relatively late compilation, largely, if not wholly, consisting of excerpts from older works. It begins, for instance, by copying almost verbatim the whole of chapter i of HA., Book I (corresponding in content to the first part of ML., i) . Like HA., T is composed mainly in sloka, with some prose passages. But it also contains many stanzas in the more elaborate kavya meters; and among these are found many (nearly one hundred) of the verses of ML., scattered in many different places. It seems to me quite evident that ML. is the older text, and, that T copied these verses either from it directly, or from some intermediate source. To be sure, T does not mention ML., though it gives the names of some of the elephant treatises which it used (see my note 39, on ML., v, 2). But this proves nothing, for it does not mention HA. either, though it certainly copied at least one large section of it. The composite character of T is most clearly shown by its repetitiousness. Frequently it treats the same subject twice or even several times over. Usually these duplications are juxtaposed to each other (see, e.g., my note 39, just mentioned). Some-times the same subject is treated in extenso, even repeating the same verses (perhaps quoted from different older works ?), in widely separated parts of T ; for instance, in the long passage containing ML., xi, 10, 13, 18-23 (see my notes to these verses). One definite proof that ML. is older than T is found, as I think, in the quotation in T of ML., iv, 1, a verse which surely was originally composed by the author of ML., since it refers (with prakpradesa) to an earlier part (chap. ii) of ML. itself. T is not only repetitious but very prolix; like HA., its style suffers by comparison with that of ML.

1.The place of elephant-lore in Indian literature SANSKRITISTS have long known of the existence of a technical "elephant-science" (gaja-sastra) in ancient India, represented by several Sanskrit works which have been preserved to modern times.' With their passion for systematic, technical treatment of all subjects which interested them, it would have been strange if the Hindus had failed to pay this tribute to a beast which has always played such a prominent part in the lives of their rulers. For Indian kings made use of elephants from very early times, partly for ceremonial display, partly as one of the four recognized divisions of the army (the others being infantry, cavalry, and chariots). In the latter respect they may be said roughly to have corresponded to heavy artillery, before the days of gunpowder. It is well known that the Persians learned from the Indians to use them in war, and passed on this knowledge to the Hellenistic Greeks.

Like other subjects of importance for royal courts, the Hindus treated elephantology as a branch of the Arthasastra, the science of state- craft or government. It goes without saying that the care and training of elephants must have been chiefly a function of state officials ; few private individuals can have had the means to carry it on. Accordingly, we find, as the Preface has indicated, that the oldest Indian treatise on statecraft, the Kautiliya Arthasastra, which is variously dated from ca. 300 B.c. to ca. 300 A.D., includes (though only in brief compass) the old-est data we have on elephantology, chiefly in the form of a dissertation on the duties of the Overseer of Elephants, who was one of the recognized officials of a king. From then on no Hindu work on political science ignores the subject of elephants. In addition, independent works on the subject began to be composed, as also on the subject of horses, another branch of the Arthasastra. All the known texts agree in attributing the founding of scientific elephantology to a mythical sage Palakapya, whose supernatural origin is told in the bizarre story recorded in the Matanga-lila, i,17-18. They likewise agree in making him reveal this elephant-lore first to an apparently mythical Romapada, King of Anga’ whose name is not otherwise known. Indeed, the three elephant books known to me are all composed in the form of dialogues between these two personages.

References to elephants abound, of course, throughout all Indian literature. They furnish countless similes to the poets. A careful study of all such references would undoubtedly show a much more widespread knowledge of the technical "science of elephants" than has been generally supposed. There is good reason for believing that some acquaintance with this branch of learning was quite general among educated men. It follows that without some knowledge of it not a few passages in general Indian literature can hardly be understood. All Sanskritists will remember the familiar verse in the drama sakuntala in which the general compares the king to a "mountain-ranging" elephant. But I venture to guess that few have ever thought that there was any special significance in the word "mountain-ranging" (giricara). I confess that I, at least, had always taken it simply as a vague, decorative epithet, which might have been applied to any elephant at all. Now I realize that it refers instead to a particular type of elephant, the technical description of which in the elephant-science was quite well known to Kalidasa, who clearly alludes to it.' In contrast with the rather wide spread of this technical knowledge in ancient times, it has fallen into sad neglect more recently. Not only has it been practically ignored by western Indologists ; even Indian scholars seem to have lost touch with it. This neglect seems to date back some centuries at least, to judge from the fact that the best-known ancient Sanskrit lexicons (kosa), those exploited by Boehtlingk and Roth in their great dictionary, contain only fragments of the special vocabulary of this subject. The Matanga-lila is a short work, consisting of only 263 stanzas ; yet it contains over 130 words-one for every two stanzas-not defined in the senses here found in any lexicon known to me, whether Hindu or western. Not all these words, to be sure, are strictly technical elephant words ; but most of them may be called so, and the total number is certainly significant and symbolic of the general ignorance of the subject that has come to prevail.

**Contents and Sample Pages**