Bhamati of Vacaspati on Sankara's Brahmasutrabhasya (Chatuhsutri) (An Old Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDH343 |

| Author: | S.S. Suryanarayana Sastri and C. Kunhan Raja |

| Publisher: | The Adyar Library and Research Centre |

| Edition: | 1992 |

| ISBN: | 8185141096 |

| Pages: | 623 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.6" X 5.5" |

| Weight | 810 gm |

Book Description

Foreword

It is a pleasure to know that Vacaspati's Bhamati on the first four Sutras will now be available to students of Indian Philosophy in an edition brought out in the orthodox style, with a critical introduction, Sanskrit text, English translation and notes. All those interested in Indian Philosophy will be deeply grateful to Mr. S. S. Suryanarayana Sastri and Dr. C. Kunhan Raja of the Philosophy and the Sanskrit Departments of the Madras University for bringing out this very useful work. While Sankara's Bhasya is fairly well known among students of Indian Thought, the later thinkers are practically neglected. Vacaspati presents one great section of Advaita Vedanta and his Bhamati is second in importance only to Sankara's Bhasya.

The Introduction, besides dealing with the date of the work and place in the Advaita tradition, gives a clear and careful account of the central ideas of the Bhamati: the authoritativeness of scripture and its compatibility with reason, the nature of Avidya and its seat, release-ultimate and relative-and Brahman and Isvara, among others. There are side reflections on similar views in Western thought which are always interesting. The work will not only add to the reputation of its authors but also help to popularize Vacaspati's views on Advaita Vedanta.

Preface to the New Edition

Bhamati: Catuhsutri, Vacaspati Misra's commentary on Samkara's Bhasya on the first four Brahma sutra-s, was published by the Theosophical Publishing House in 1933. It contained an elaborate Introduction and Notes, and an English translation by Professor C. Kunhan Raja and Professor S. Suryanarayana Sastri. This book was very well received by students and scholars, and has become almost a classic in the field. It has been out of stock for a long time and there has been a persistent demand for reprinting it. The Adyar Liberary and Research Centre has great pleasure in bringing out a reprint of the same to meet this demand.

The Bhamati is the most ancient, complete and elaborate available commentary on Samkara's Brahma-sutrabhasya. It started the Bhamati school of Advaita, though some of the features of this school can be traced back to Mandana Misra, an elder contemporary of Samkara, traditionally identified with Samkara's pupil Suresvara. The other school of Advaita, called the Vivarana School, is associated with Prakasat man's Pancapadika commentary on the Bhasya, now available only for the catuhsutri portion. Many of the features of this school can be traced back to Suresvara.

Prof. S. Kuppuswami Sastri has pointed out (Introduction to Brahmasiddhi) that 'most of the distinctive features of Vacaspati's school have their roots in Mandana's views as set forth in the Brahmasiddhi, and most of the distinctive features of the Vivarana school are derived from Suresvara's views as set forth in the Varttika-s and the Naiskarmyasiddhi.' If the Bhamati School and the Vivarana School ultimately originate from Mandana and Suresvara, the tradition about the identity of Mandana and Suresvara becomes ridiculous. This is the point of view taken by Prof. Hiriyanna and Prof. Kuppuswami Sastri. Of course, a convert need not necessarily be consistent with his pre-conversion views.

In the beginning of the Bhamati Vacaspati refers to two kinds of avidya (anirvacyavidyadvitayasacivasya prabhavato vivarta yasyaite viyadanilatejobavanayah). Mandana has also recognized two kinds of avidya-non-apprehension (agrahana) and misapprehension (anyathagrahana). According to Mandana meditation or upasana is necessary for completely removing the second variety of avidya, and for converting the first indirect knowledge of Brahman (paroksajnana) into the direct Brahman-realization (aparoksabrahmasaksat-kara). Suresvara is against this duality of avidya (Brhad. Varttika, p. 1065, verse 199).

Vacaspati follows Mandana's views about the relation between Prasamkhyana and Brahmasaksatkara. Meditation (upasana or prasamkhyana) on the meaning of the Upanisadic mahavakya-s proclaiming the identity of Brahman and jiva is accepted by both as leading to the direct realization of Brahman. Suresvara criticizes this view in his Naiskarmyasiddhi. Samkara distinguishes jnana or knowledge which does not involve any action and dhyana or meditation which is mental action. According to him when there is a choice to do or not to do, doing involves action; jnana is awareness which does not involve a choice, and therefore does not involves action. In the Padesa Sahasri (1.3.112-116) Samkara recognizes and recommends pari samkhyana-he does not call it dhyana or concentration. It is a kind of recapitulation and reflection. It seems to be a kind of awareness which does not involve action.

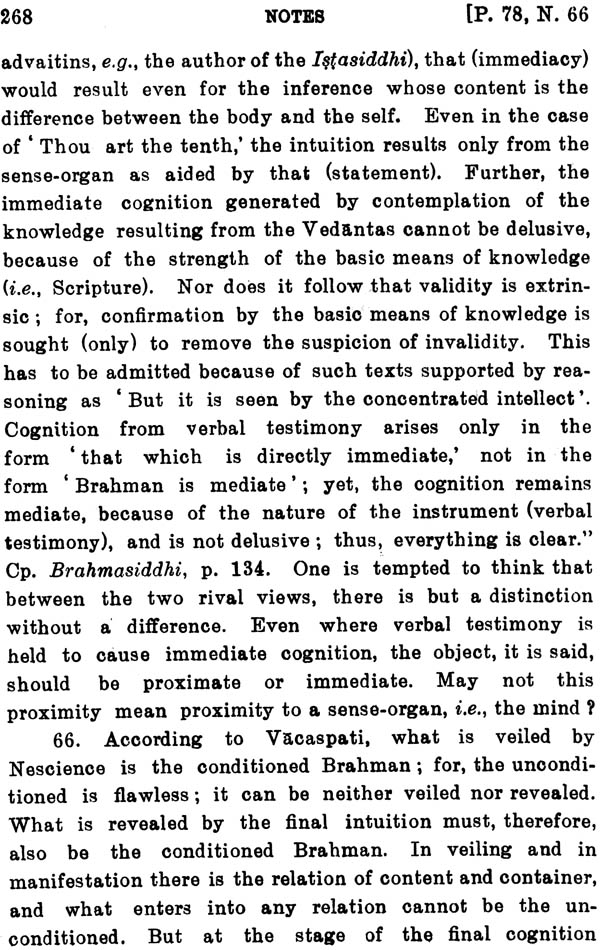

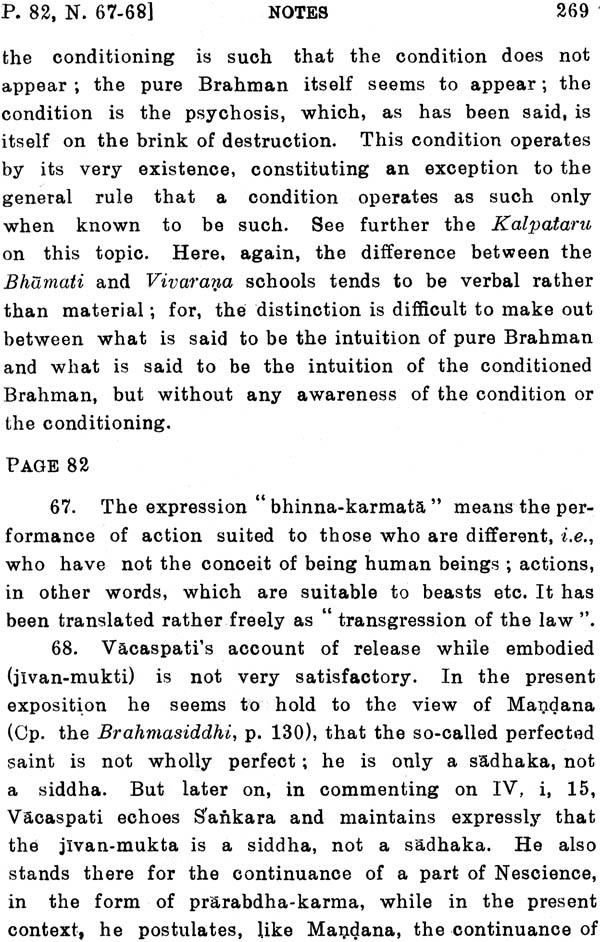

Regarding the locus of avidya there is difference of opinion between the Bhamati and the Vivarana schools. According to Vacaspati and Mandana, the individual soul (jiva) is the locus of avidya, while Brahman is the object (visaya). According to the Vivarana School and also Suresvara, Brahman itself is both the locus (asraya) and the object (visaya) of avidya. According to the Bhamati avidya-s are as many as the jiva-s, but the Vivarana school accepts only one avidya, with different modes.

Regarding the nature of jiva and Isvara the Bhamati School accepts the Avacchedavada, while the Vivarana School follows the Pratibimbavada. Vacaspati considers that Brahman conditioned by maya or avidya is jiva, while Brahman that transcends maya is Isvara. According to the Vivarana school Brahman reflected in maya and its product mind, is jiva, while Brahman chich serves as the original is Isvara; Brahman under-goes reflection in avidya or maya and mind. Suresvara's view is slightly different. The reflected image of Brahman in maya is Isvara, and the reflected image of Brahman in mind is jiva. Isvara and jiva being reflected images are indeterminable. This is the Abhasa-vada.

There are many minor differences between the Bhamati School and the Vivarana School, but on fundamental points they agree. (Brahma satyam jaganmithya jivo brahmaiva naparah).

Vacaspati is one of the most outstanding authorities on the different branches of Indian philosophy with excellent authoritative works to his credit. Besides the Bhamati in the field of Advaita, his Nyaya-varttikatatparyatika on Uddyotakara's Nyayavarttika is a standard work on Nyaya and has been commented on by Udayana. His Tattvabindu is an original work on the theory of sentence-meaning according to the Bhattamimamsa School, criticizing even the sphotasiddhi of Mandanamisra. He has commented on the Brahmasiddhi and the Nyayakanika of Mandana. He has also ommented on the Samkhyakarika and the Yogasutrabhasya. His Nyayasucinibandha gives its date of composition as 898; if taken as the Vikrama era this will be A.D. 841, if Samvat, it is equivalent to A.D. 976. Prof. Raja and Sastri take the former view.

Paul Hacker's argument that Vacaspati refers to the Nyayamanjari and must therefore be later than Jayantabhatta need not be taken seriously, since it is now clear that the Nyayamanjari referred to by him is not Jayantabhatta's work, but that of Vacaspati's teacher Trilocana. But Vacaspati refutes Bhaskara in his Bhamati, and cannot be earlier than the ninth century since Bhaskara criticizes Samkara; Vacaspati also quotes Salikanatha in his Tattvabindu and Sali-kanatha has quoted Umbeka. Vacaspati must certainly be earlier than Udayana who flourished towards the close of the tenth century since he has ommented on the Nyayavarttikatatparyatika.

Traditionally Vacaspati is considered to have been a Maithila Brahmin. According to some he belonged to a village called Bhama near the Nepal frontier' according to some others he belonged to Bedagama on the eastern boundary of Darbhanga. Umesh Mishra believed that Vacaspati belonged to Tarhi in the Darbhanga district. Vacaspati refers to one Nrga as his patron; many attempts have been made to identify him, but without success.

The English translation is intended to help the students to understand the Sanskrit text; and is faithful to the original. The Introduction and Notes will clarify many of the difficult passages of the text, and explain the views of Vacaspati Misra on Advaita. Relevant views from western philosophy have been pointed out to clarify some of the issues. Prof. Radha-krishnan's remarks in his Foreword regarding the value of this publication is relevant even now.

| Preface to the New Edition | v |

| Foreword | xi |

| Introduction | xv |

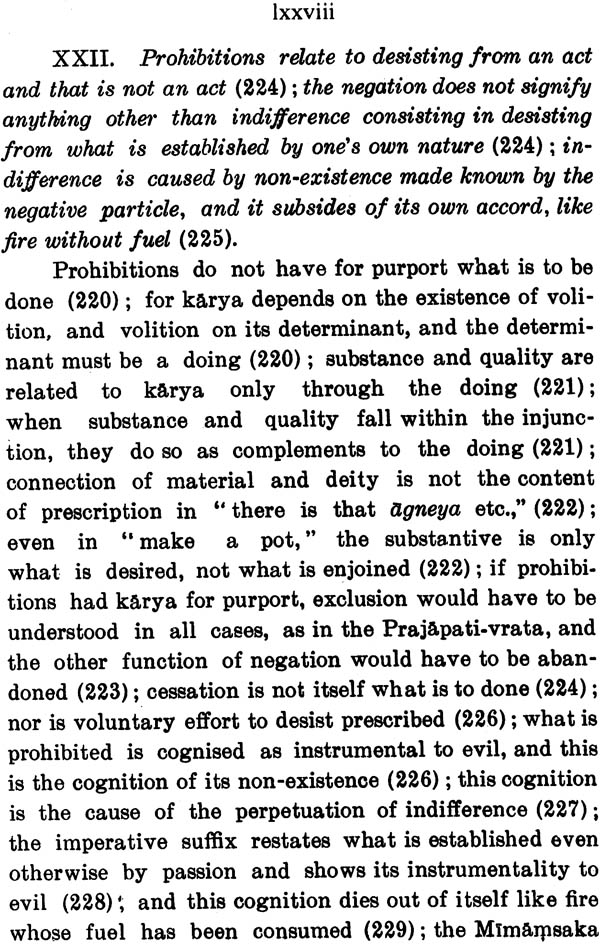

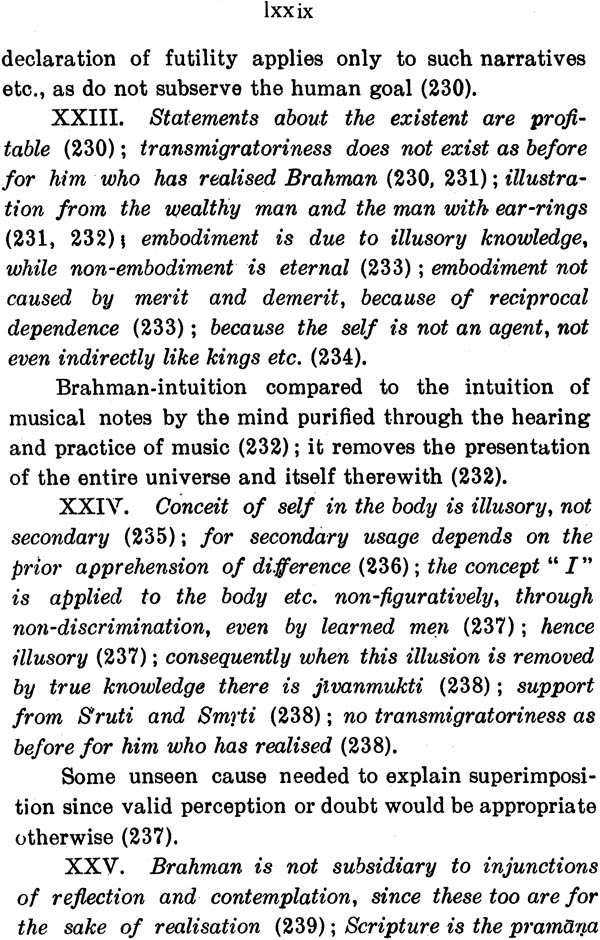

| Detailed Table of Contents | lix |

| Text and Translation: | |

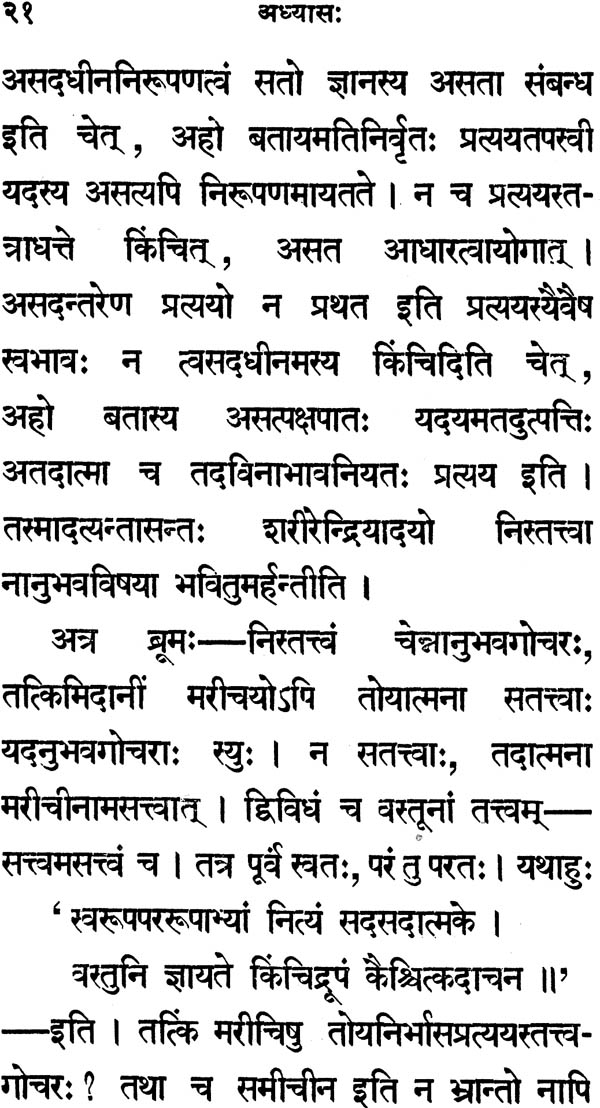

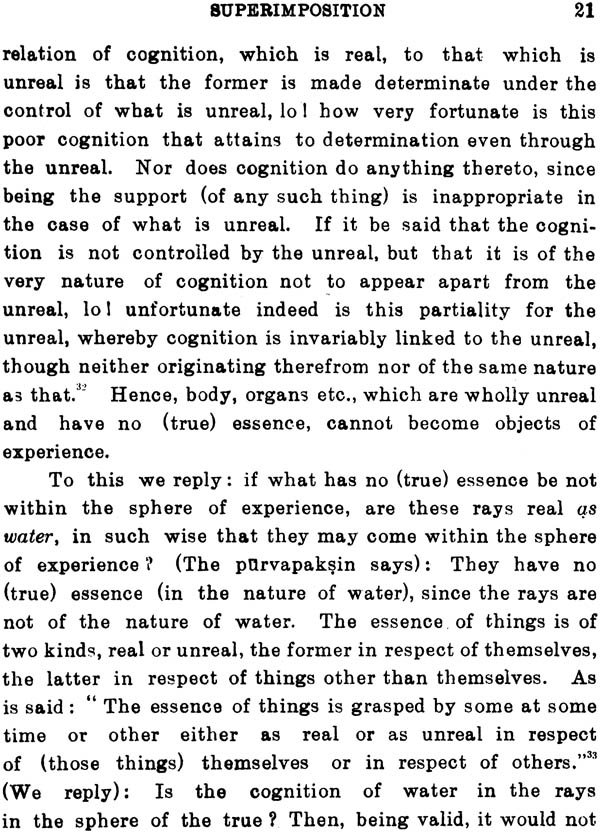

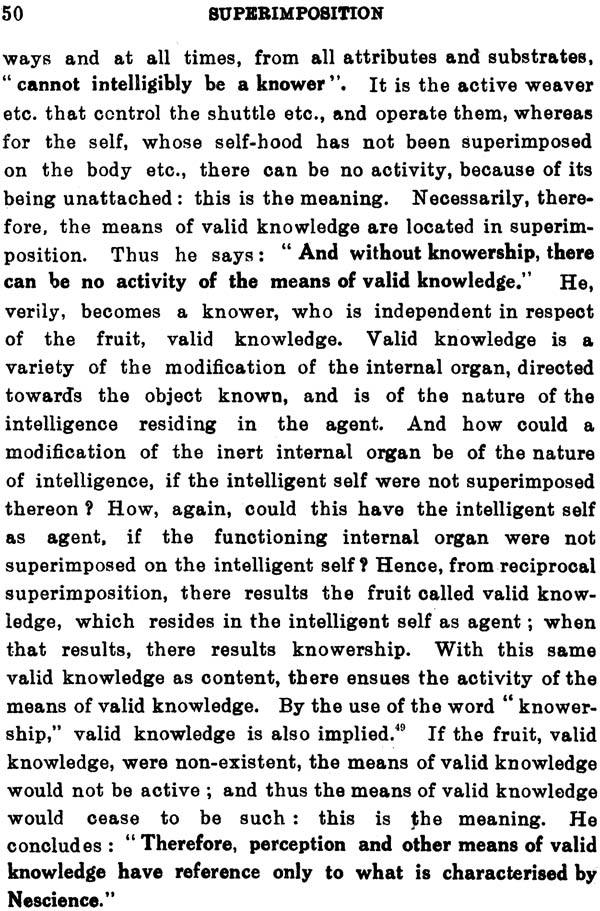

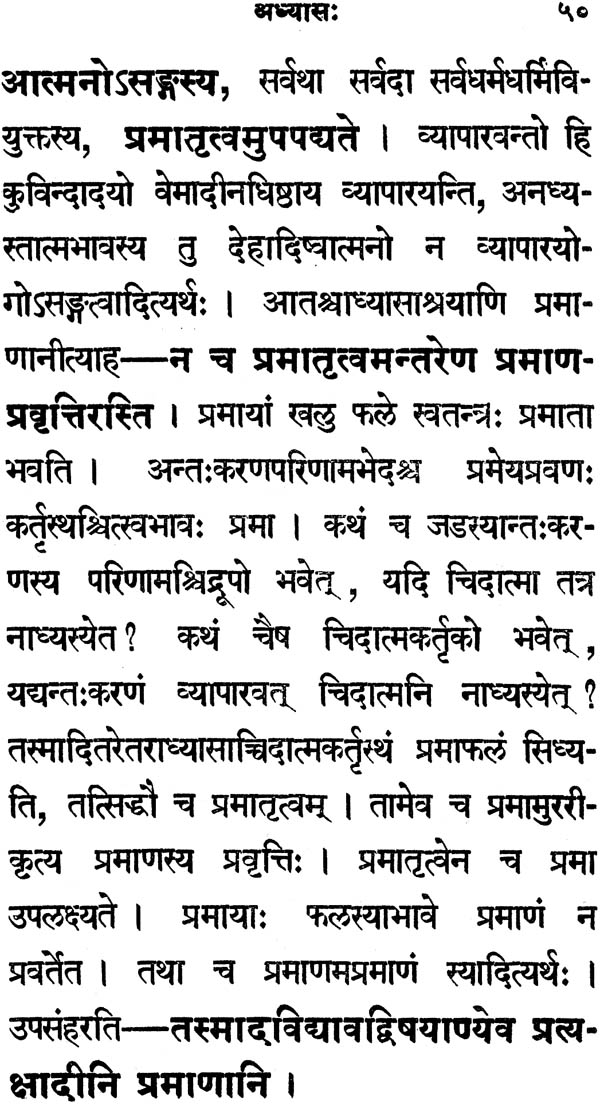

| Superimposition | 1 |

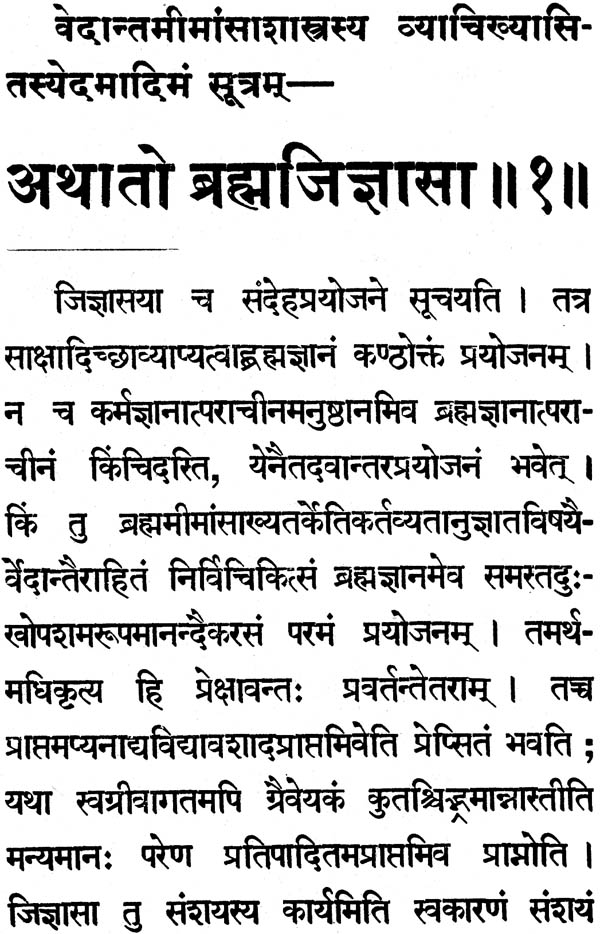

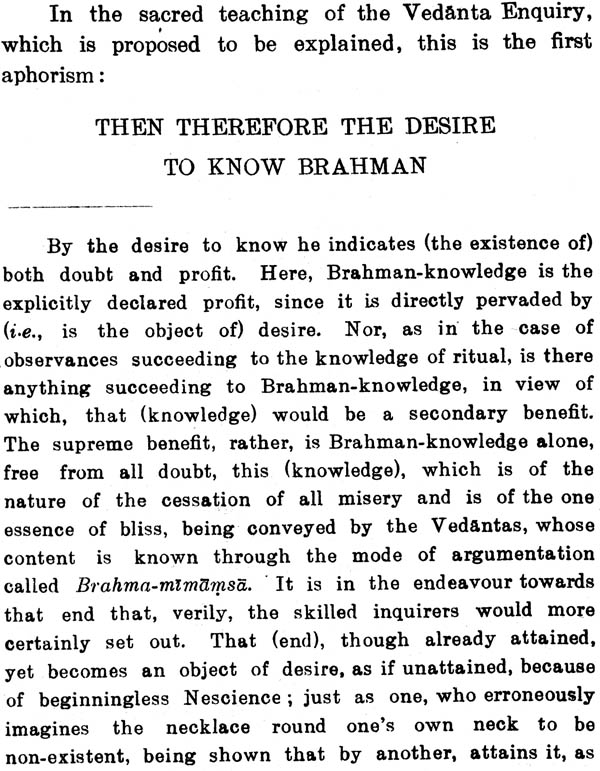

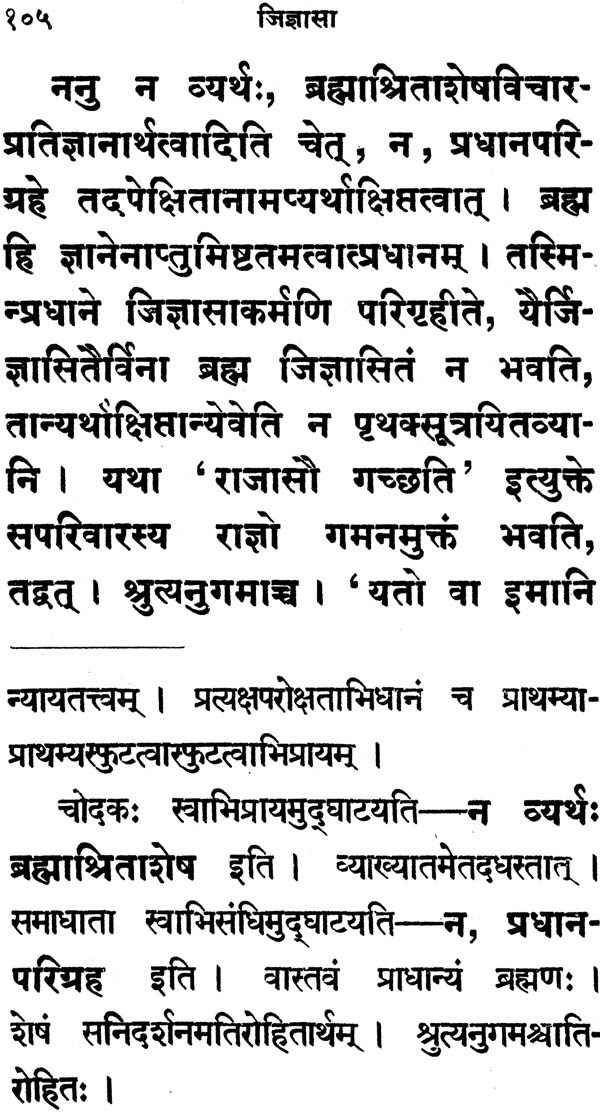

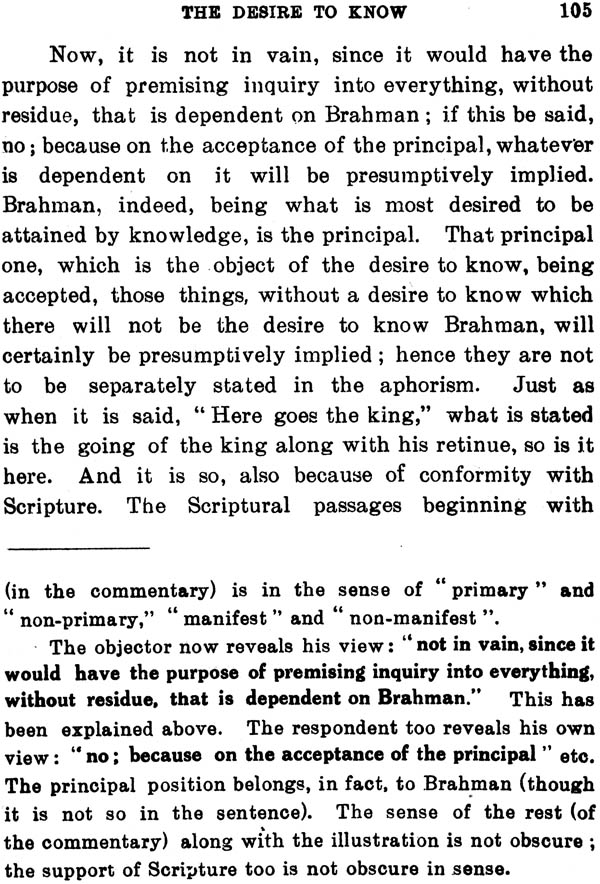

| Desire to Know | 63 |

| Definition | 119 |

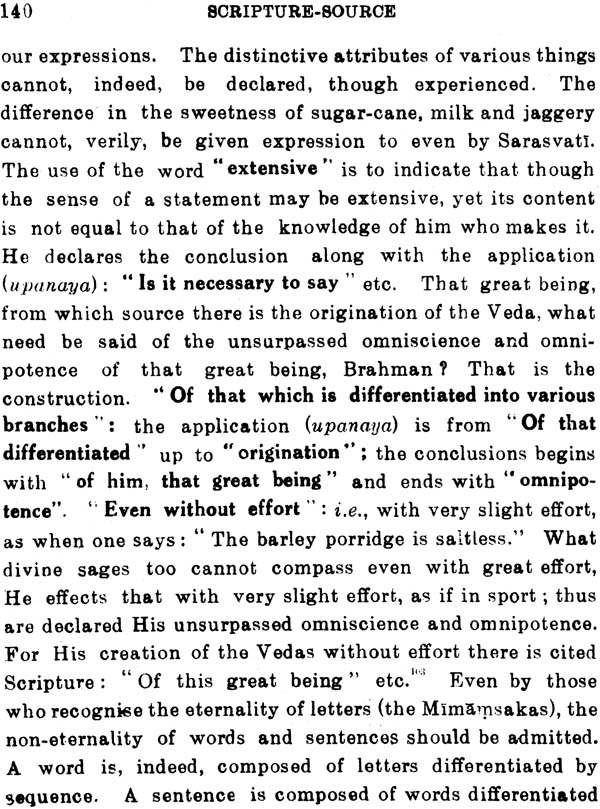

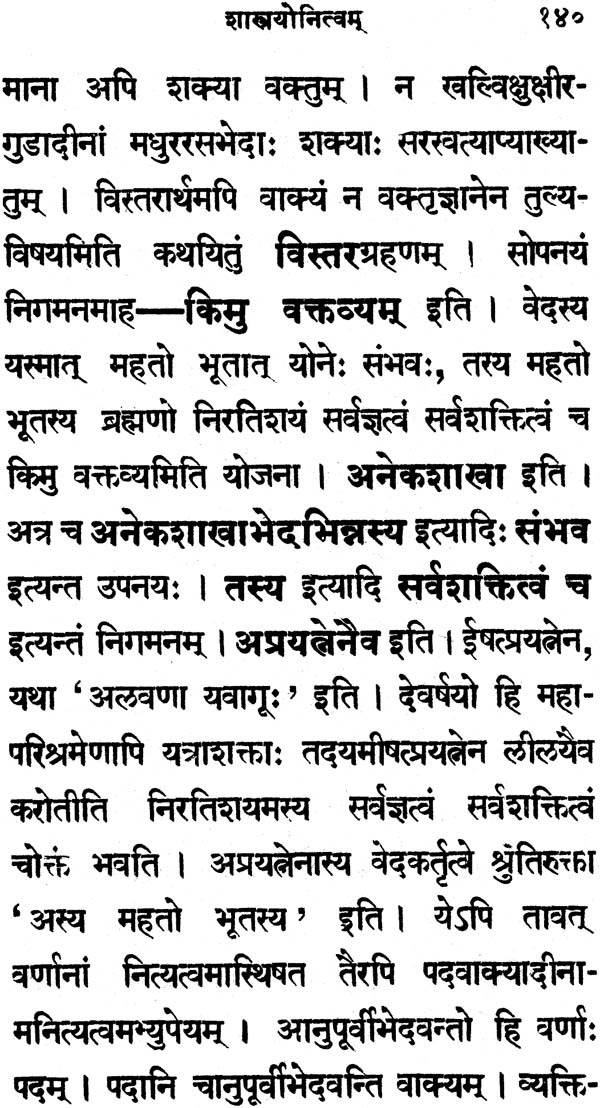

| Scripture-source | 137 |

| Harmony | 145 |

| Notes | 247 |

| Additional Notes | 297 |

| List of Abbreviations | 313 |

| Corrections | 315 |