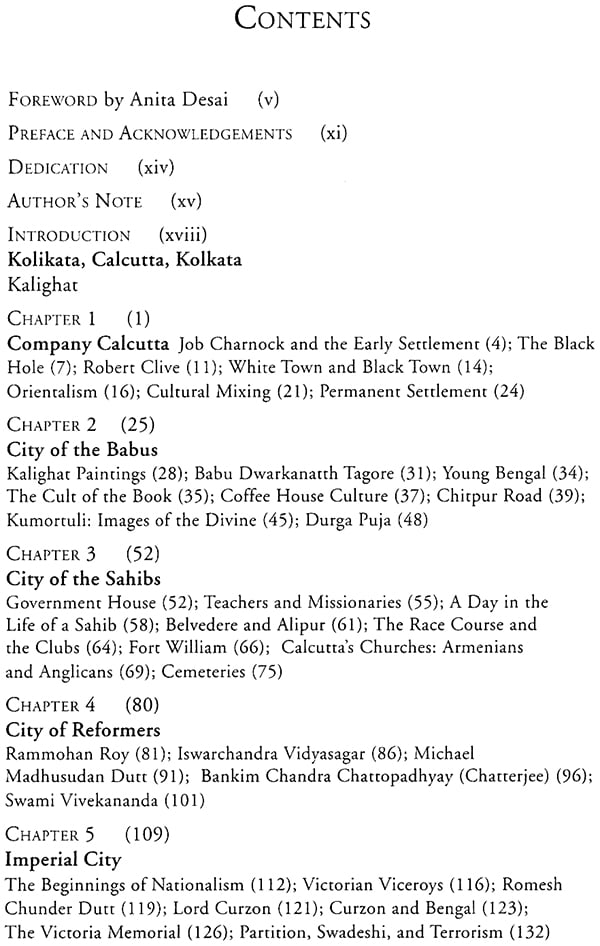

Calcutta- A Cultural and Literary History

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAV959 |

| Author: | Anita Desai |

| Publisher: | Supernova Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 9788189930684 |

| Pages: | 254 (13 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 230 gm |

Book Description

In the popular imagination, Calcutta is a packed and pestilential sprawl, made notorious by the Black Hole and the works of Mother Teresa. Kipling called it a City of Dreadful Night, and a century later V.S. Naipaul, Gunter Grass and Louis malle revived its hellish image. This is the place where the West first truly encountered the East. Founded in the 1690s by East India Company merchants beside the Hugli River, Calcutta grew into India’s capital during the Raj and the second city of British Empire. Named the City of Palaces for its neoclassical mansions, Calcutta was the city of Clive, Hastings, Macaulay and Curzon. It was also home to extraordinary Bengalis such as Rabindranath Tagore, the first Asian Nobel laureate, and Satyajit Ray, among the geniuses of world cinema. Above all, Calcutta (renamed Kolkata in 2001) is a city of extremes, where exquisite refinement rubs shoulders with coarse commercialism and political violence. Krishna Dutta explores these multiple paradoxes, giving personal insight into Calcutta’s unique history and modern identity as reflected in its architecture, literature, cinema and music.

Krishna Dutta was born and brought up in Calcutta. She has translated Bengali literature and written several books on Rabindranath Tagore.

When one asks oneself if Kolkata can be called ‘a great city’, is one merely asking if it is historic, important, wealthy, grand and imposing? I think another, less definable quality is called for, the quality of myth, and that ‘a great city’ is one that possesses a reality that verges on the mythical. A book that portrayed the city would be insufficient if it presented only details of its history, climate, architecture and civic life; it would need to go beyond and convey the indefinable and non-substantial that make the city even greater in the mind than it is on the ground.

I do believe that Kolkata possesses such a quality because I have seen how profoundly it has affected anyone who has lived in it (and I say lived with reason, not merely visited). I did not set eyes on it myself till I was twenty years old when my father died, our house in Old Delhi was given up and the family moved to Bengal where my brother and sisters had all found employment. Yet it had been present in my life in the form of my father, a Bengali albeit not from Kolkata, for whom the city had always been a destination. He grew up in the countryside of East Bengal, spoke to us of the luminescent green of the rice fields, the riverine life of the people, and the fish and coconuts and rice of his cuisine, the finest in the world, he gave us to understand. I would see his eyes come to life and glow if he heard a snatch of baul music from his land, and I remember the expression on his face as of one who had seen a vision, when we went together to a matinee show of Satyajit Ray's first film, Pather Panchali. Sometimes a tangible piece of that world came our way in the form of an earthen pot of date palm syrup, or a box of Bengali sweets, the soft milky sandesh, each shaped like a conch shell and packed in rice for freshness. These spoke to us of another culture, a more subtle one. A visitor from Kolkata, on opening a suitcase to unpack, would release a particular odour into the air-damp, mouldy, deltaic, even swampy-that was totally alien to our own arid surroundings. It was as if a large, dark moth had blundered into the crackling dry air of the north. This Kolkata has been most elegantly evoked in Nirad C. Chaudhuri’s chapter on the city in his Autobiography of an Unknown Indian. In it he exactly replicated my father’s experience of going as a country boy from East Bengal to study in the great ‘second city of the British Empire’. It is a piece of prose I can read and reread with unfailing pleasure: that line about ‘the feathery and shot effect of the Calcutta sky’ and what lay beneath it as ‘a crowd of misbehaved and naughty children showing their tongues and behinds to a mother with the face of Michaelangelo’s Night’!

Trying now to retrieve my impressions on first seeing Kolkata as that newly graduated twenty-year old with a vague sense of launching upon a literary career, I remember that my first reaction was that although I came from the capital of India, Kolkata was the first true metropolis I had seen. Delhi in the 1950s, even New Delhi, was really nothing more than a handful of villages clustering together on the sand and dust of the northern plain. Kolkata, by contrast, seemed to pulse with a sense of purpose, a confidence in its ratson d étre. The reason may have been taken away when the capital moved to Delhi but a tradition had been established and habits formed. One saw it in the confident flow of traffic up Chowringhee, in the orderly variety of the markets. Here was no compromise between city and suburb; here was city. How wonderful, I thought, to have piped gas supplied by the city, so a flame leapt up at the turn of a knob! In Delhi we might as well have been camping in the desert, the way we had to construct our lives, but here the city constructed our life for us, making us city-dwellers, not junglees. What was more, in Delhi my attempt at breaking into journalism or publishing had been dismissed with scorn whereas in Kolkata I quickly became a member of a Writers’ Workshop held regularly on Sunday mornings where everything I wrote was considered with flattering seriousness. The city had a sophistication about it, 1 thought, to be found in the delicious sandesh from Ganguly’s as well as the pastries from Flury’s, and the immaculately starched muslins worn by Bengalis. Not to speak of the night-long concerts of classical music that only bloke up at dawn, and the film club where I first saw the films of Eisenstein and Bergman.

To counterbalance all this urbanity and sophistication, there were the fervent rites and rituals of worship of the goddess Kali, at times in her ferocious and at other times her benign aspect as the mother goddess, Durga. Also the elaborate rituals of lesser ceremonies like those associated with marriage-all in the heat and humidity, to the lowing of conch shells and wreathed in the heady fragrance of tuberoses. In fact, there was a certain murkiness about the city, too. I thought it had to do with the gas lamps along the shadowy streets, the tides that rose and fell on the inland river, the reflection of tall houses in the still, dark ponds that took the place of city parks and squares. But it was much more than that: a covert danger and implicit violence that warned one that the various currents of city life swirled around in it, restless and unresolved-the past and the present, the rich and the poor, the literate and artistic and the illiterate and hungry. They contradicted each other at every turn: the smog that smothered the city could be of winter mist or of factory smoke, the monsoon rains could be cooling and refreshing or intemperate and disease-ridden, the colour red could be festive and celebratory or a signal of danger and violence... In his reminiscences of his childhood in the city, Rabindranath Tagore wrote, ‘Something undreamt of was lurking everywhere, and every day the uppermost question was: where, oh where would I come across it?’

In 1990, Calcuttans celebrated Calcutta’s tercentenary. With a cultural zeal characteristic of Bengal, they published books, organised seminars and exhibitions, wrote poems, composed songs, and held parties. Yet only ten years later, many of them began lobbying to change the name of the city. Soon the West Bengal Government passed a constitutional amendment. From 1 January 2001, the beginning of the new millennium, Calcutta was officially renamed Kolkata.

The demand for renaming came from scores of writers, poets and other Bengali-speaking cultural figures. They argued that the new name would reflect the pronunciation of the city’s name in Bengali and would protect the state’s linguistic identity. (In general, Bengalis say Kolkata — with a fairly long ‘o-amongst themselves and Calcutta to the rest of the world.) But other influential Calcuttans, no less Bengali in background, were less convinced. The novelist and activist Mahasweta Devi remarked, "We wanted a change, but what will happen to the names of our venerable institutions? Will Calcutta University be renamed Kolkata University or Calcutta High Court be Kolkata High Court from now?’ The film-maker Mrinal Sen commented, ‘We can see an assertive cultural movement here, which speaks about making it mandatory to paint signboards in Bengali. Will it help us to integrate with the world? I am not sure.’ Annada Shankar Roy, an octogenarian litcérateur said, ‘I’m vehemently opposed to the decision which will make a mockery of the history behind Calcutta's name. You can pronounce the name of the city differently, but how can you change the spelling that has evolved over a period of time? Besides, phonetically and linguistically Kolkata and Calcutta go hand in hand.’

There were yet other possibilities for the name change, given the cosmopolitan nature of the city, in whose labyrinthine lanes jostle turbaned Sikh taxi drivers from the Punjab, tobacco-chewing Bihari and Oriya labourers from neighbouring Bihar and Orissa and dark- skinned accounts clerks from southern India—not to mention Marwari businessmen from Rajasthan, Sindhis and Gujaratis from western India, Bangladeshis and Assamese from the east, the Chinese community which has adopted Indian citizenship, and many other groups. Most inhabitants of the city are partially bilingual, constantly switching between Bengali and English, Bengali and Hindi, and combinations of these languages with other regional tongues such as Urdu, Telegu and Malayalam, in cacophonous conversation. Meanwhile, the shop signs and film advertisements on Kolkata’s roof tops may be among the earliest examples of multilingual posters anywhere in the world, with Bengali script cosying up to English and Hindi lettering without somehow appearing incongruous. Hence, for Bengali villagers the city is pronounced Kolkata; for many Bangladeshis it is Kolikata; for the Oriyas it is often called Kalikata; the Punjabis, Gujaratis and others from the rest of India nearly always call it Kalkatta. Perhaps it is not surprising that in an opinion poll published in the Calcutta edition of Telegraph in mid-2000, fifty two per cent of Calcuttans thought renaming the city was unnecessary and only thirty eight per cent were in favour, while the rest were undecided.

For the majority Bengali community, the new name, Kolkata, suggests a compromise between acknowledging the city’s colonial past and the need to restore its threatened identity as a Bengali city. They want to avoid the British-given name Calcutta but they also do not like the original Bengali name of the place, Kolikata, that of a swampy fishing village. ‘Kolkata sounds natural but Kolikata sounds comical,’ said a young person in English, when I was chatting in Bengali to a group of students and teachers at my old college in the city. Bengalis have always been acutely aware of how they relate to the rest of the world, particularly the English-speaking world. Thus, for them, the new name serves as a natural, if unconscious metaphor for the cultural fusion in the city’s architecture, art, literature and other artistic manifestations. After all, Bengal, and especially its capital city, is where the East first came face to face with the West its intellect as well as its colonial brutality-and responded creatively to the encounter through Bengali culture. Rather than taking a strongly nationalist stance, like Bombay which changed its name to Mumbai, or Madras which has become the unrecognisable Chennai, Calcutta preferred a comparatively minor name change, which frankly is a bit of a multicultural mishmash.

But how did the name—whether Kolikata or Kolkata—originate? What does it mean, if anything? Although reams have been written on the subject, the name remains a mystery.

There is a story that when one of the first British arrivals inquired about the place, a bewildered grass-cutter took the question to be, when was the grass cut? Not knowing any English he replied in his own tongue, ‘kal kata’-cut yesterday. This was duly noted down as the place-name.

A bizarre and more lugubrious explanation comes from early missionary sources that liken the name to Golgotha, the place of the skulls where Jesus was crucified. Calcutta was of course a very unhealthy spot for its early European inhabitants and large numbers died here. (We shall visit their graves in the Park Street cemetery in due course.)

In one of Woody Allen's films, Mia Farrow threatens to leave New York and do charity work in Kolkata, and Woody is aghast: the place has ‘a hundred unlisted diseases!’ he cries. Sitting in a London cinema, I catch myself suppressing a solitary sigh. To Kolkatans, the depiction of Kolkata in the international media as a packed and pestilential metropolis crawling with destitutes is as irritating as the old stereotype of New York as the world’s number-one murder capital muse no doubt be to New Yorkers.

Hence, yet another book on Kolkata. Written by a former Kolkatan who now lives in London, this book tells the story of a city with admittedly fading physical charms but with remarkable cultural richness. Since the early nineteenth century, Kolkata has nourished a wide range of writers, painters, musicians, actors and filmmakers, not to mention thinkers and scientists. Its exterior may have been grimy, but its inner life was always the most exciting in India. It was also a great city of commerce, politics and religion, expressed through its many temples and festivals. After all, Kolkata, once the City of Palaces, is where the British empire in India became wealthy and powerful in the eighteenth century and where today, in a post-communist world, ghost of Marxism still clings precariously to government. In spite of its many contradictions and some terrible disasters during the twentieth century, the city somehow manages to regenerate itself. Anyone who wants to understand modern India has to visit Kolkata.

The river Hugli (Hooghly) gave birth to the city. Its broad curve running from north to south, flowing towards the Bay of Bengal, slices the city in two unequal halves. On the west is the main railway station at Haora (Howrah), Belur Math (the international headquarters of the Ramakrishna Order) and the Botanical Garden founded in 1787 by the East India Company, containing a huge 250-year-old banyan tree. On the east is the main part of the city: north, central and south.

Chourangi(Chowringhee), described in Chapters 3 and 5, is the central area of Kolkata where the Europeans settled. As the colonizers pushed the original inhabitants out of the centre in the early eighteenth century, north Kolkata flourished, as we shall see in Chapters 2 and 4. During the second half of the nineteenth century, south Kolkata slowly evolved from the southern end of Chowringhee Road, although there were earlier settlements in Alipore (Alipur) and Kidderpore (Khidirpur). But Kolkata was never a planned city. It grew haphazardly around the port, the old fort and the ancient Barabazar market by the river.

There are four bridges linking the halves of the city, and about twenty ghats on the riverbanks. Ferry services operate from some of these ghats. The most northerly bridge is the Haora (Howrah) Bridge, now called Rabindra Setu after the city’s most famous citizen Rabindranath Tagore. It was originally a pontoon bridge, built in 1874; the present 27,000-ton steel structure, built for the war effort in 1943, is a cantilever bridge. Fifteen hundred feet long, it feels like the busiest bridge in the world, carrying approximately two million people daily and myriad types of transport (although trams no longer ply its tracks). Farther south, the second bridge, Vidyasagar Setu, opened in 1992, is a cable-stayed toll bridge and comparatively less crowded; it is a road link from Kolkata to Mumbai, Delhi and Chennai. Vivekananda Bridge, also known as Bally Bridge, farthest to the south outside the city, is both a road and rail bridge. It was built in 1931 and was originally known as Willingdon Bridge.

Apart from the railway station at Howrah, the other major railway station, Sealdah, founded in 1862 in central Calcutta, is also connected to major cities all over the country. Right up co the 1950s, Sealdah Station used to have a special loading platform to transport Kolkata’s refuse to a garbage disposal area at Dhapa in the southeast of the city.

The colonial heritage -discussed throughout this book-makes it almost impossible to standardise the English spellings of Kolkata's people and places. For instance, Bose and Basu are equivalent spellings of the same name, as are Mitter and Mitra, Tagore and Thakur; ditto Datea/Dutta/Dutt, Roy/Ray and Chowdhury/ Chaudhuri, and the situation is still more complicated for names like Banerjee, Chatterjee and Ganguly. So far as possible, I have retained the spellings for famous individuals that are widely accepted, for example Subhas Chandra Bose, Rabindranath Tagore and Michael Madhusudan Dutt, and standardised the rest, which vary widely in common use. With place-names I have generally retained the period spelling but given the modern spelling in parentheses, for instance Kidderpore (Khidirpur), but in a few cases, where the two names differ radically, I have used the modern spelling with the older spelling in parentheses, for example Sutanuti (Churtanurty/Soota Loota). As for street names, many were changed in the period after Independence in 1947; to avoid confusion, a list of equivalents appears on page 248.

**Contents and Sample Pages**