Celebration of Love: The Romantic Heroine in the Indian Arts

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDE323 |

| Author: | Ed. By. Harsha V. Dehejia |

| Publisher: | Lustre Press, Roli Books |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2004 |

| ISBN: | 8174363025 |

| Pages: | 303 (Color Illus: 134) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.2" X 9.2" |

Book Description

continues to shine for learned men

only while it is not eclipsed

by the tremulous lashes of women's eyes

In one of those indescribably opulent paintings from the Chaurapanchashika series, the heroine. Champavati is seen leaving her palace chamber and moving into a garden where flowering trees spread their lush foliage and lotuses blossom in a small cistern of water. Everything that one associates with this brilliant group of paintings is in place here: rich, saturated colours, emphatically simplified architecture, dazzling patterning on textiles, star-like flowers that refuse to rest on cushions and simply levitate in the air, a strip of the sky that insists on peeping at the scene from one corner. Set in the midst of all this, as Champavati, that statuesque beauty, moving like a wild goose' in the poet's words, reaches out and plucks a leaf from the tree flowering in her garden, some bumble-bees bhramars- hover around her face, forming a perfect circle, or aureole, as it were. The vignette is delightful, but there is no mention of this detail in Bilhana's verse inscribed in the top register of this folio: n fact, nothing ever of the garden or the chamber with its flag bearing makara-gargoyle, appears in the verse which speaks, in that familiar, wonderfully nostalgic vein, only of the poet remembering her, 'even now': a fragile fawn-eyed girl,/ her body burning with fires of parted love, / ready for my passion-/ a beauty moving like a wile goose, bringing me rich ornaments.

The painting, considering that not much specific detail can be picked up from the verse apart from a generalized description of Champavati's fragile beauty and her 'wild-goose'-like gliding movement- is made up therefore of other elements. And one needs to begin reading the painting in its own terms. For, in the process of putting it together, conjuring it up as it were, the painter falls back upon the resource of his own imagination, bringing in details, throwing out suggestions, creating cultivated ambiguities. And, in the process, he invites us to expand the meaning of some things. Of the bhramaras hovering around Champavati's face, for instance. A reminder as it always is of the presence of the lover, the bhramara nectar-loving, inconstant creature, whom one encounters countless times in literature comes into this painting rather naturally. But perhaps there is more than this, even of the bhramaras, in the work. Nothing is clearly stated, and ambiguities, multiple suggestions, abound. A single bhramara, one notices, has strayed in the direction of the blooming lotus in the pond: all others or is it just one bhramara whose circular movement is being tracked, even perhaps the very same bhramara that had headed first in the direction of the lotus and then wisely changed its mind?- stay close to Champavati's face. In this, is a suffestion being raised, one wonders: that of the bhramaras becoming confused by the sudden presence of this beauty in the garden and being unable to make up their minds whether to head for the lotuses in the cistern or towards her lotus-like eyes, the fragrance of her body, her radiant face? Again, is there meaning in the manner in which the colour and the form of the black bhramara seem to be taken up and repeated, almost endlessly: in the pom-poms attached to Champavati's armlets, in the scalloped knots and braided length of the dark tresses and pigtail, in the serried row of tassels attached as finials to the starched, end of the nayika's gauze-like veil.

There are, obviously, other things, besides bhramaras, that need to be read closely, here as in countless other pointings. In doing all this, one could go wrong, of course. And discriminations lucid light, in Bhartrihari's words from the Shringarashataka, might well be eclipsed by the tremulous lashes of women's eyes, especially when it comes to reading paintings on the theme of love. Some things are certain, however. The painters, as distinguished from the writers of texts that we celebrate, knew what they were doing: opening situations up, saying things that had not been said, declining to stay with linear meanings, creating different layers of thought. The ambiguities that we seen in some works are intended and often they constitute an invitation to the viewers to expand the meaning of things according to their own wont, or their ability/energy-utsaha, in other words to enter the work.

One needs to take deep interest in the manner in which the painters break free of categories sometimes. The nayika-bheda, as theme, is an example. Poetic texts classify and categorize, for often that is precisely the framework. In pursuit of the effort to establish a clear category, or type, many details would naturally be left out, many references eschewed. However brilliant the verses, therefore, it would be in the nature of these descriptions to become too focused, even dry sometimes. My sense is that the painters saw their task differently: their medium allowed them different opportunities, and they were comfortable in introducing different 'textures'. To take an example: while a vasakasajja might be recognized instantly as a vasakasajja in a painter's rendering, he was also apt to bring into his rendering other details, other reference, that might go well beyond the demands of the text, or serve as reminders of other things. In the surroundings he could create, in the elements of nature of architecture that he could bring in, it must have been tempting, and easy, for him to move into the wide world of similes and metaphors, for example. Signifiers could be established, symbols drawn upon. One sees this being done, to stunning effect, in paintings of the great 17th century Rasamanjari that Kripal painted in Nurput/Basohli. The text on which the paintings are based barely speaks of them, but as the painter 'renders' the verses in his own medium and manner, he brings in rich, vivid details that interpret and enhance the mood of the work. In these paintings, as has been observed, 'chambers move away or come close; the doors close or open or remain half-closed, arches appear and disappear; steps are introduced and taken away. Likewise, those magical trees that belong to the botany of the imagination rise tall and firm, or shrink, cluster together or scatter. The background changes from crimson red to orange to yellow to dark gray and white. Raindrops fall in one part of the painting and not in the other. Nothing happens: the bounding character of line, the exquisite richness of decoration, forms impinging upon borders, the glow cast by beetle-wing cases, the flutter of scarves, the perilous tilt of beds, the garlands that lie curling on them. Not one of these things, one known, figures in the text.

Reading works, especially works like these, is not easy. But even more difficult is the reading of works in which the painter seems to go consciously beyond known categories, or creates deliberate ambiguities. One can take several example, but the one which comes most readily to mind is that sumptuous painting in the Rasamanjari mould, which comes most readily to mind is that sumptuous painting in the Rasamanjari mould, which is now is the Museum of Fine Arts at Boston. A young woman, tall and lissome, dressed in a resplendent gold-coloured peshwaz, stands close to a tree, holding in one hand a flower that she gazes at with those languid eyes 'whispering into her ears'. Her legs are lightly crossed: one bare foot, she having just removed it from an elegant slopper, is slightly raised, toes touching the earth behind her: with the other hand she clutches a slender branch of the magnificent flowering tree close to which she stands. Facing her and looking up at her stands another maiden, slightly shorter but also slender of frame, dressed in a blue peshwaz, a double-gourded vina resting on her shoulder, one hand poised to move over and pluck its strings. A golden veil is thrown elegantly across one shoulder of hers, much in the manner of the high-born lady whom she faces, but the jewellery she wears beetle-wing cases simulating the luster of emeralds is not as rich, and her feet are bare. Behind her, next to the thin trunk of a tree at far left, a deer stands, head raised, pert look in the eyes. Flanking the two maidens on either side rises a tall, thin cypress, emphasizing their slim, attenuated forms; behind them gray, pulsating streaks of misty smoke swirl in the air against a dark background; and, above everything, some birds have taken to wing under a band of scalloped clouds hanging in the sky, with golden lightning darting, snake-like, through them.

It is a luminous painting, evocative and jewel-like. Instantly one senses the presence of passion, longing, in the air the startling, swirling cloud of mist or smoke alone charging the viewer's mind each element serving to enhance the mood, every detail crisply executed. But what exactly is the situation, the moment, that the painter portrays here, remains unclear. In respect of style, the work is evidently very closely related to the early Rasamanjari series, but thematically, it does not belong to that text, the situation here not being something that comes from any known verse of Bhanudatta. What, then, is it, one wonders? Has the painter decided to go beyond established categories, and create some of his own? Is it something left unsaid by the poet that the painter ahs decided to say in his own manner? The nayika- one could designate the principal figure thus-comes very close to being an utka, 'she who waits for him longingly at the trysting-place'; the ragini she with the vina on her shoulder has all the aspect of Todi, especially with the deer who stands directly behind her. But what is it that brings them together in this dark if illumined corner of a grove, under a threatening sky, in the evening hours in which birds seem to be on their way home? In the texts do a nayika and a ragini ever meet, even though we know that the nayika-bheda and the ragamala have much imagery in common? Again, are we right in presuming that the maiden in the blue dress is a ragini, and not some music-loving companion of the nayika who has also made her way to this spot? Do the clouds in the sky have some special meaning or message here ordinarily they do not belong to the 'iconography' of are they simply an unthinking carry-over from another painting, like one treating of an abhisarika? Again, in the tree close to the nayika, here seen in dazzling bloom, is there some distant reference perhaps to a vrikshaka or shalabhanjika some distant reference perhaps to a vrikshaka or shalabhanjika some yakshi at whose were touch it has sprung suddenly to glorious life?

A reading of the painting is not easy. There is no text inscribed at the back, and there are no easy answers within the painting, for so much is left unsaid. It is possible at the same time that this visually exciting, challenging, ambiguous work was, in respect of its theme, intended to be what it is: a puzzle, a painter's equivalent to what in the literary world used to be described as vivid-aushadham, 'the ultimate test of a learned man's learning.

Not each work may be a test of a learned man's learning, but paintings of the themes that are spoken of here need certainly to be seen with the same keenness of eye and mind with which they were painted.

As We Light the Lamps

It is uddipan vela, the moment when lamps are lit, and as the shehnai resonates and as we gather flowers it is time for the celebration of love to begin. And this is no ordinary celebration, for we begin a festival of the recognition and exaltation of the romantic nayika in the Indian arts.

Sensuous and yet spiritual, bridging the gap between the secular and the sacred, evocative of heart throbbing love and equally of heart rending longing, inhabiting enchanted spaces in courts and havelis, throbbing with delight in pleasure gardens and forests, resonating in ragas and raginis, reverberating with the colours of the seasons, the foot falls of the romantic nayika have been heard in the Indian tradition for millennia. She is celebrated in poetry and painting, in dance and music, temples and sculptures and in her persona there is the coming together of the rasas of shringara and bhakti.

Shringara rasa or the artistic expression of the romantic emotion is considered a raja rasa, the king of emotions, for it has an unsurpassed majesty and grandeur and within it are the many nuances and meanings of what it is to be human and equally the quest of the human for the sublime and the ultimate.

This volume will examine the various aspects of this nayika, the many facets of her romantic emotion, its depiction in the paintings of the Rajput courts of Rajasthan and the Pahadi region of the Himalayas, her place in the genre of ragamala and barahmasa paintings, her special valorization in the Sufi narratives, her appearance in Jain and Buddhist representations, her presence in folk songs and calendar art and above all investigate the central position that she occupies in the Vaishnava tradition.

As we celebrate the nayika it becomes clear that there are multiple streams in the Indian tradition that contribute to its development. There is the classical stream which recognizes her demure and courtly persona, graceful and proper, even as it places her in the matrix of dharma, whose genesis is in the Natyashastra and who is best seen in Sanskrit drama and temple sculpture. Then there is the folk stream which throws up the earthy, robustly passionate nayika, spontaneous and free in her love and uninhibited in her liaisons, whose prototype is the gopi of the Bhagavata Purana and which animates the Gita Govinda and enlivens the Rasamanjari. And then there is the Tantric nayika, cultured and sensitive and adept in the many erotic arts, as exemplified by the courtesan. In separating these three strands it is important to realize that these are merely different sutras of the same fabric, or three prismatic images of the same shringara rasa which resonates and radiates in the Indian civilization and is the cynosure of our attention in this festival of love.

If there is one image that seems to capture the quintessence of the romantic heroine it is that of a sensual woman looking at herself in a mirror as she adorns herself. Proud and self-assured she applies the finishing touches to her face and makes a final check of her appearance, and looks in the mirror, not only to reconfirm her own beauty, but in earger anticipation of meeting her beloved she looks longingly to find out if she can see her beloved reflected in the mirror, for ultimately her beauty is an offering to him. And as she does this she breaks into a sweet smile, even in anticipation and longing of that special moment when his eyes would light on her face and she would celebrate that romantic moment in his delight. When they meet, perhaps they will hold the mirror together, and as they see themselves together in the mirror they will find confirmation of their love, and the two hearts and minds will become one, for there is in that radiant moment of beauty when the two lovers become one, the very meaning of romantic love. There is in this image not only the vibrating prakriti of trembling sensuality but equally the serenity of purusha and a majestic spirituality, there is in that image the pride of a beautiful woman but equally the surrender of that pride to one she loves, there is in that image the unique individuality of a nayika but equally there is the melting of that into a larger wholeness of love, there is in that romantic moment a delight of the sense but equally a realization of the true self, as ultimately romance is when prakriti and purusha merge joyously into a radiant ananda. The nayika is all this and more, for she is the perfect embodiment of shringara rasa for us in the Indian tradition and in seeking her in the arts we discover ourselves. A doha of Kabir comes to mind:

lali mere lala ki jita dekhun tita lal

lali dekhana main gayi main bhi ho gayi lal

To that beautiful festival of love a cordial susvagatam, to you. Welcome. Let us together celebrate the nayika.

From the Jacket:

Harsha V. Dehejia has gathered a galaxy of scholars from around the world to take the reader on a journey that celebrates the romantic heroine in the Indian arts. It is a visually rich journey which takes us to opulent havelis and bucolic groves, temples and courtyards, where we meet kings and nobility and also artists and artisans, as we hear whispers of gopis and the footfalls of Krishna. We encounter the nayika in miniature paintings and temple sculptures. Pothis and calendars, dance and music but above all hear resonances of her heart throbbing longingly in our own selves for ultimately the nayika in the Indian tradition is a paradigm of the perennial quest of mankind for a divine and transcendent love.

At the heart of the many and varied artistic expressions of the romantic sentiment is the nayika or the heroine. Her various adornments and trysts, the many moods of her love realized through amorous moments of longing or belonging her strong presence in the Krishna lore and equally in the Suff narratives. Her portrayals in the Ragamala and the Barahmasa traditions of poetry and painting, through the beautiful depictions in miniature paintings as well as popular arts, have captivated our attention through the many centuries of Indian artistic representations. Her footfalls have been heard in courts and temples. She has been celebrated by the raja and the praja, she has a presence in homes and mansions and her persona resonates in enchanted forests and groves. She is all this and more, but above all she is the epitome of perfect beauty and the paradigm of the seeker of ultimate reality.

In these essays, she comes alive in all her splendour and radiance. She captures our attention through her sheer sensuality as she looks into the mirror and prepares for that special moment. She delights in the many romantic situations and brings alive the concept of bhakti shringara or a certain spirituality that can only arise from indulging in love, but above all she stands self-assured and dignified, whispering that not only is there truth in love but that love is truth.

About the Author:

Harsha V. Dehejia, who has a double doctorate, one in Medicine and the other in Ancient Indian Culture, both from the Univeristy of Mumbai. India has a deep and abiding interest in Indian Aesthetics and specially in the artistic expressions of the romantic emotion. He is a practicing physician and Professor of Religion at Carleton University. He lives in Ottawa, Canada.

| The Things Unsaid B.N. Goswamy

| 8 |

| Uddipan Vela, As we Light the Lamps Harsha V. Dehejia

| 14 |

| The Genesis o the Nayika in the Natyashastra Bharat Gupt

| 17 |

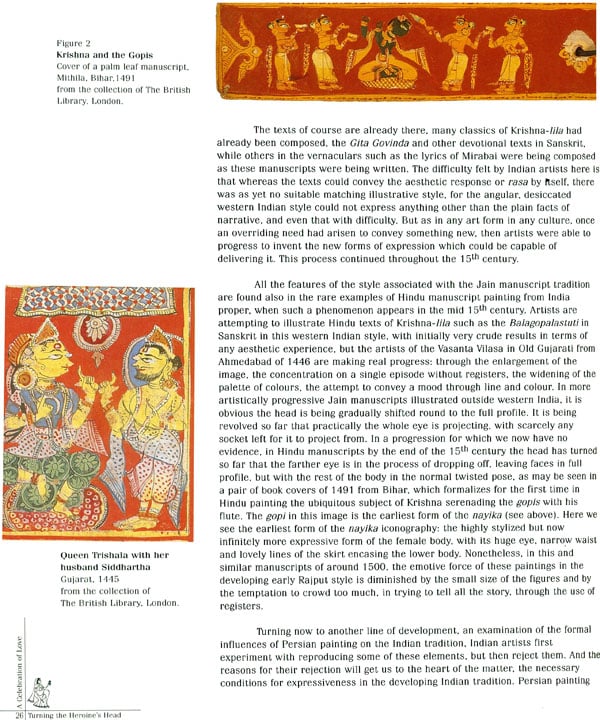

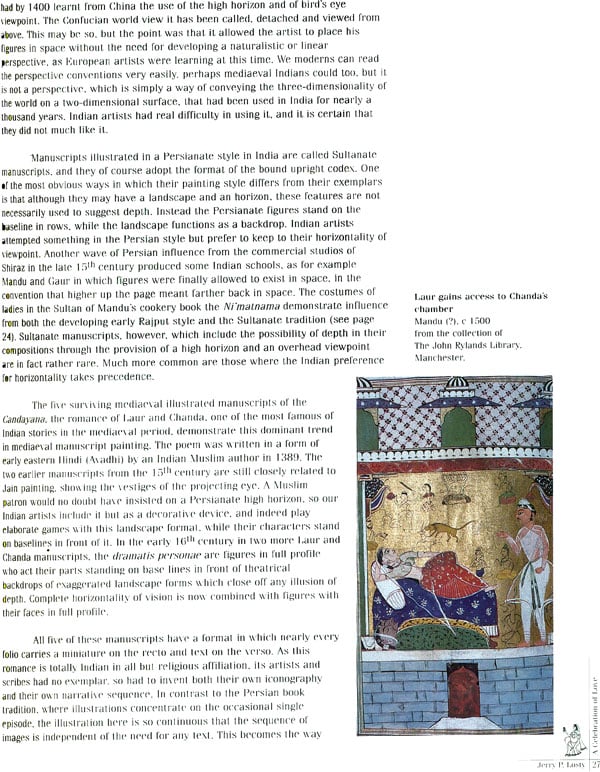

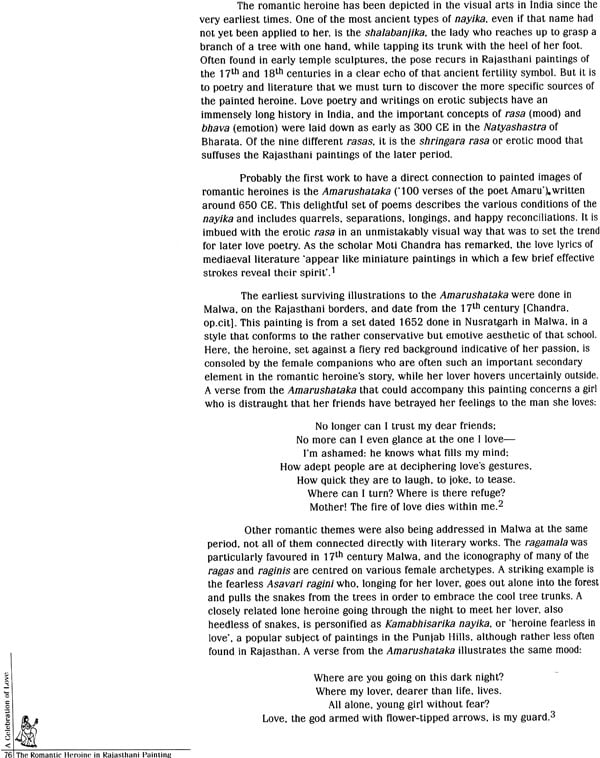

| Turning the Heroine's Head: The Emergence of the Nayiuka Form in Mediaeval Indian Manuscript Painting Jerry P. Losty

| 23 |

| The Quest for Krishna Walter Spink

| 30 |

| Footprints in the Dust The Gopis as a Collective Heroine in the Bhagavata Purana Caron Smith

| 38 |

| Myriad Moods of Love Alka Pande

| 44 |

| Karpuramanjari: The Artless Heroine Lalit Kumar

| 54 |

| The Sufi Nayika: Qutban's Mirigavati Aditya Behl

| 60 |

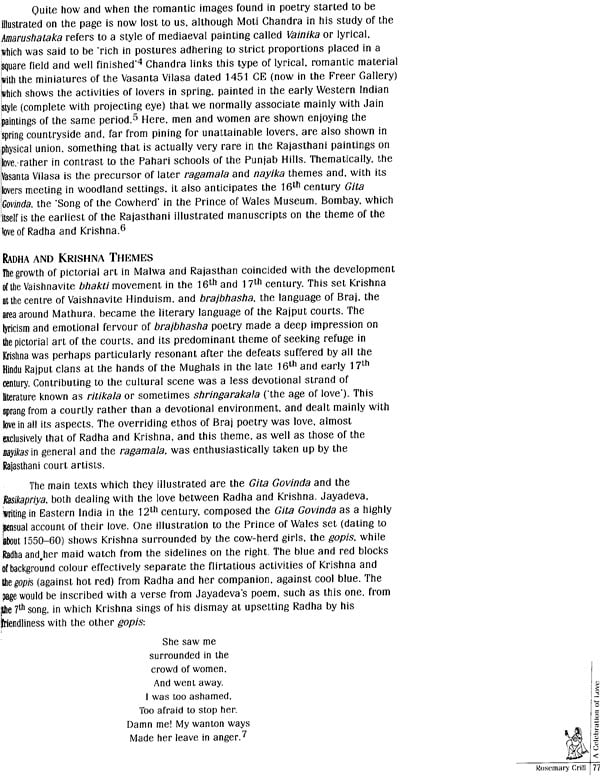

| The Romantic Heroine in Rajasthani Painting Rosemary Crill

| 74 |

| Nayikas in the Haveli of Shrinathji Amit Ambalal

| 86 |

| A Life as Svamini Imbibing the Bhava in Pushti Marg Meilu Ho

| 90 |

| The Multiple Veils of the Beloved Jasleen Dhamija

| 100 |

| The Heroine's Bower Framing the Stages of Love Molly Emma Aitken

| 105 |

| Radha in Kishangarh Painting Cultural, Literary and Artistic Aspects Navina Najat Haidar

| 120 |

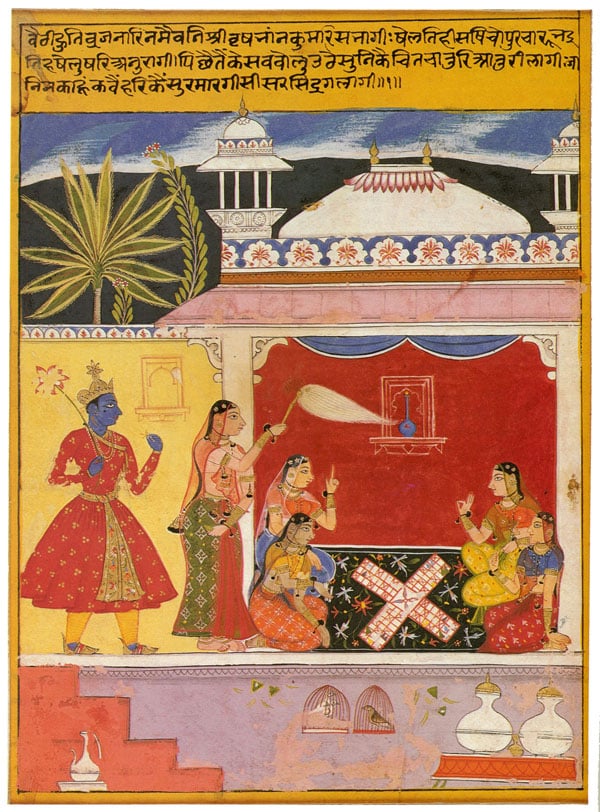

| The Nayika of Sahibdin Usha Bhatia

| 130 |

| The Rasikapriya of Keshavadas Text and Image Shilpa Mehta (Tandon)

| 134 |

| Connoisseur's Delight The Nayika of the Basohli Rasamanjari V.C. Ohri

| 141 |

| The Nayika in Barahmasa Paintings Kamal Giri

| 148 |

| Awash in Meaning Literary Sources for Early Pahari Bathing Scenes Joan Cummins

| 154 |

| Dancing to the Flute Jackie Menzies

| 163 |

| The Nayika of the Deccan Jagdish Mittal

| 165 |

| Pious Love Iconography of the Nayika as a Devotee Kim Masteller

| 176 |

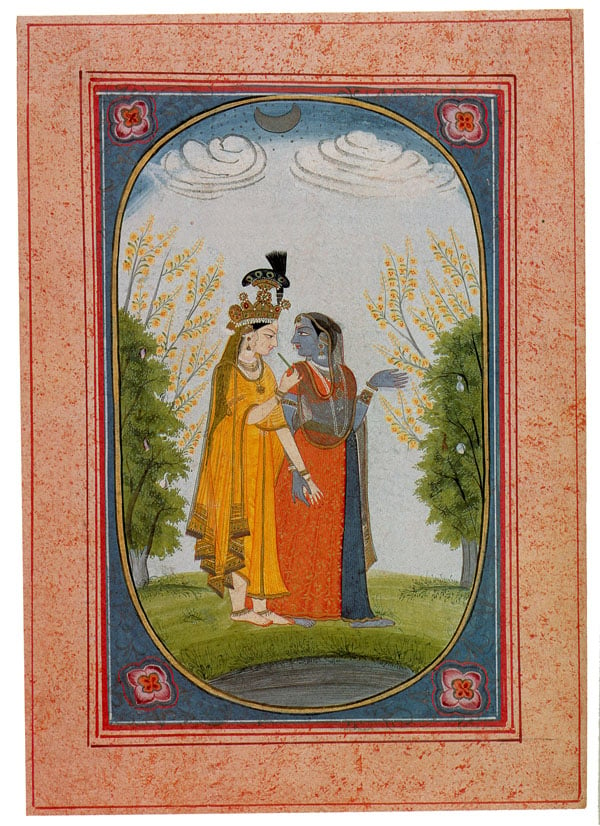

| Adorning the Beloved Krishna Lila Images of Transformation and Union Rochelle Kessler

| 186 |

| The Aesthetics of Red in Rajasthani Painting Naval Krishna

| 193 |

| The Nagas and the Kanya The Romance in Painting Gurcharan S. Siddhu

| 198 |

| The Raas Lila The Enchantment with Innocence Geeti Sen

| 208 |

| Nawabs and Nayikas The Romantic View from the Court of Lucknow Rosie Llewelyn-Jones

| 215 |

| The Indian Courtesan Symbol of Love and Romance Pran Neville

| 220 |

| The Romantic Nayika: A Dancer's View Shanta Rati Misra

| 226 |

| Sri Radha The Supreme Nayika of Gaudiya Vaishnavism Steven J. Rosen

| 230 |

| Radha: The Goddess of Love in Bengali Folk Literature Sumanta Banerjee

| 236 |

| Radha Bhava and the Erotic Sentiment The Construction of Feminity in Gaudiya Vaishnavism Madhu Khanna

| 244 |

| The Mughal Nayika P.C. Jain

| 248 |

| Wife, Widow, Renunciant, Lover The Mirabai of Calendar Art Patricia Uberoi

| 251 |

| Shringara and Love in Early Jain Literature Shridhar Andhare

| 258 |

| The Nayikas of Nagarjunakonda Elizabeth Rosen Stone

| 263 |

| The Nayika in Ayppati The Tamil Vrindavan in Periyalvar's Periyalvartirumoli Srilata Mueller

| 266 |

| The Nayika and the Mirror Devangana Desai

| 274 |

| The Nayika and the Bird Amina Okada

| 278 |

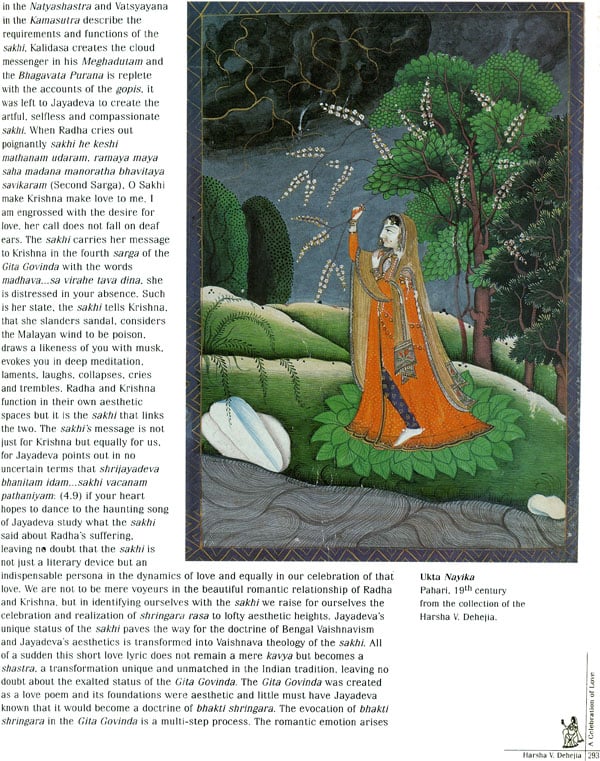

| The Vaishnava Ethos and Shringara Bhakti Harsha V. Dehejia

| 286 |

| Vidai: As We Float Out Lamps on the River Harsha V. Dehejia

| 300 |

| Contributors | 303 |

to all international destinations within 3 to 5 days, fully insured.

to all international destinations within 3 to 5 days, fully insured.