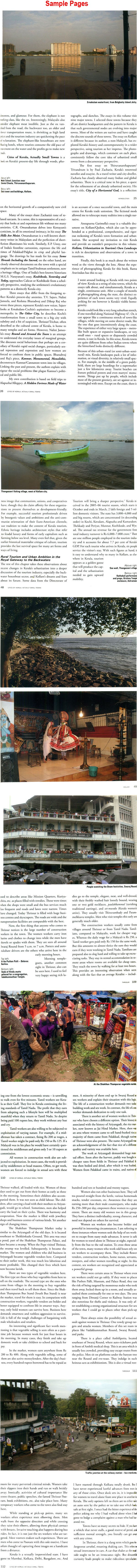

Cities of Kerala: Actually Small Towns

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAK806 |

| Author: | Baiju Natarajan |

| Publisher: | Marg Publications |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2008 |

| ISBN: | 9788185026848 |

| Pages: | 160 (Throughout Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.0 inch x 8.5 inch |

| Weight | 940 gm |

Book Description

Foreword

I first became aware of Kerala in 1952 as an undergraduate in St Stephen's College, Delhi. This was before the official formation of the modern state of Kerala as part of the Indian Union in 1956 by joining the two indigenous kingdoms of Travancore and Cochin that had owed allegiance to the British Crown. Soon in my history class I learned of the antiquity of the name of the state which appears in a slightly different form in the edicts of the Maurya Emperor Ashok (c. 269-232 BCE) as "Keralaputra", literally "the sons of Kerala". There were several students both in the college and in the university, who spoke Malayalam. The name of the language obviously derives from Malaya or Malayadesh, the general designation of the coastal region more familiarly known by its derivate Malabar, which has such romantic associations. Later on in Sanskrit literature I encountered the popular conceit of the soft breezes of Malaya mountains heavy with the fragrance of sandalwood and cloves. It was also during those undergraduate days that I became acquainted with the art of Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906), perhaps the best known Keralaputra after Shankaracharya.

I first visited Kerala during the winter of 195859 when I was contemplating my doctoral research on the architecture of Nepal at Calcutta University. A group of us travelled all the way from Calcutta (now Kolkata) to Trivandrum (now Thiruvananthapuram) by train via Madras (now Chennai) to attend the annual Indian History Congress. It was not only the first professional conference I attended but also my debut presentation of a paper on art history. Thus my long professional career was launched in modern Kerala. The greater excitement, however, was that the newly formed state had the first Communist government on the subcontinent led by E.M.S. Namboodiripad who was to deliver the keynote address at the conference attended by thousands of historians from home and abroad. As Bengalis and students of Calcutta University, we were all to a degree influenced by Marxism and therefore for us it was truly an exciting occasion.

I don't remember much about the Congress itself except the thunderous applause that followed the Marxist leader's speech and my own nervous but well-received presentation on a special form of the Buddhist goddess Tara in Nepal. I also have fond memories of the distinctive regional food: the delicious fish curries (elixir to a fish-loving Bengali) and the rich Muslim cuisine, especially the rice and meat dish, dripping in ghee (or was it coconut oil?), called biryani. I distinctly remember our visit to the Padmanabhaswamy Temple where I first became conscious of the distinctive architecture of Kerala. It was a revelation to find the extraordinary resemblance between the timber architecture of Nepal in the Himalaya and that of Kerala at the southernmost extremity of the subcontinent. Although the Padmanabhaswamy Temple complex was reconstructed mostly during the reign of Marthandavarma in the 18th century, from my familiarity with Stella Kramrisch's pioneering study of Kerala architecture, I realized that the form probably originated long before stone was introduced in the Dravidadesha. Over the years, on return visits to Kerala, I would note the use of the same form in the Islamic and to a lesser degree in the Christian architecture of the region. I would again encounter the same ecumenical taste in architecture in the Hindu/Buddhist and Islamic monuments in distant Kashmir, in the Himalaya. From Trivandrum we took the train south to the town of Padmanabhapur am where there are older temples with dazzling murals. We continued south to visit Kanyakumari or Cape Comorin now in Tamil Nadu.

I returned to Kerala a decade later in January 1969, this time not with historians and orientalists, but with a large group of American tourists. Not only did I become better acquainted with Kerala's classical Kathakali dance form, but I also visited the city of Cochin (today Kochi) and the famous backwaters.

One of the highlights of the trip was to watch an all-night performance of Kathakali in the sprawling complex of Padmanabhaswamy Temple. It was an enthralling and captivating experience, as much for the high quality of the performance in its original ambience as it was meant to be seen, as for the reaction of the large local audience, young and old, who sat appreciatively on the hard ground for hours with wonder and delight. Watching that live performance in the dimly lit temple compound until the first rays of the sun caught the pinnacle of the temple tower in "a noose of light" was a memorable aesthetic experience and gave me insights into the essence of both dance drama and the visual arts that I never learnt in any university course. It gave me a better understanding of Bharata's Natyashastra as well as of another Bharata who came into my life intimately for a few months in 1965-66. This was K. Bharata Iyer the great historian and exponent of Kathakali. I had the distinct privilege of working with him in setting up the American Academy of Benares (now subsumed into the American Institute of Indian Studies in Gurgaon) at Rewa Palace in Varanasi. He was an accountant by profession, a scrupulously orthodox Kerala brahman, and a scholar continuing the intellectual tradition of the region that produced India's greatest philosopher Shankaracharya more than eleven centuries ago.

The other unusual and unexpected experience was visiting Co chin for the first time. The city itself seemed no different from any other settlement, but to see the Mattancherry palace with its wonderful murals of Hindu mythology in the typical exuberant and ornamental style of painting, to walk down Jewtown leading to the synagogue with its floor of Chinese tiles next to the palace, the Dutch church and other relics of the colonial period, and, most exotic of all, the Chinese fishing nets rising above the waters like black sails silhouetted against the setting tropical sun are all vivid images m my memory.

My own city of Calcutta offers a wealth of places of worship including mosques, temples, churches, and synagogues built during the colonial period, but somehow while walking down the narrow street lined with stores owned by Jewish settlers I felt as if I had been transported to another place and another time, perhaps old Nazareth or Jerusalem of the Old Testament. I remember how excited and surprised the Jews in my group of weary American travellers were. Alas, when I returned to Cochin three decades later in 2000 with my family to show them this relic of Kerala's religious tolerance, the Jewtown had been converted to Brahman town. The Jewish traders had all left to be replaced by displaced Kashmiri brahmans. Only one Jewish family lingered on selling the lace that the ladies of the family made where I had bought some on my first visit. Another family looked after the forlorn synagogue where the Chinese blue and white tiles are no longer tread by pious Jewish feet but admired like museum pieces by tourists from far and wide.

The sight of the Chinese fishing nets silhouetted against the setting sun that today offers a picturesque subject for the tourist cameras also announces Kerala's long established link by sea with China in the east and Africa and Arabia in the west. The archaeological evidence as well as tradition attest to Kerala's fame, perhaps as early as the time of the biblical ruler Solomon, as the source of spices and peacocks since ancient times. It was certainly an important emporium for textiles and spices until the fall of the Roman empire in the 4th century. The void was then filled by Arab merchants and sailors, which explains the strong presence 'of Muslims and Islamic culture and the memorable biryani that I tasted on my first visit. The Europeans did not arrive until 1498 when the first expedition led by the Portuguese Vasco da Gama docked at Kozhikode/Calicut. (Fortunately, the name Calicut will survive in the expression "calico", a form of textile popularized by colonial trade.) It is said that what surprised the Portuguese adventurer most was encountering flourishing communities of Jews whom he wanted to destroy but was prevented by the intervention of the local rulers.

Perhaps the most romantic experience of our turn-of-the-millennium visit, and certainly the most picturesque, was the boat ride in the serene backwaters of Kerala. How relaxing and comforting it was to travel in gently rolling boats along narrow waterways lined by tall coconut trees in the lush green surrounding. Nestled in this verdant landscape were villages of whitewashed and red-tiled houses connected by narrow footpaths along the backwaters. No concrete, no cars, no pollution. It was gratifying to find these backwaters and the communities living along their banks still flourishing at the beginning of the new millennium. Neither the wealth derived from West Asia nor the urge to modernization had materially altered their intrinsic character. Nature had not yet succumbed to the onslaught of the bulldozers and earthmovers of urbanization that is inexorably altering the urban landscape of this enchanting land.

The essays and images gathered here, most of them by Malayalis, present observations in words and pictures and speak about the changes that modernity is relentlessly imposing upon some of the urban centres of Kerala. Hopefully, this foreword by a Bengali admirer of the state recording his personal and sporadic impressions of the cultural continuity and changes in Kerala will be helpful in understanding better the unavoidable evolution and transformation, the angst and exhilaration recounted by the new voices brought together in this volume.

Introduction

In Keralas mountainous Idukki district, Ramakkal Medu attracts a small number of picnickers. Here, from an eastern tip of the Western Ghats, the plains of Tamil Nadu are visible in a dramatic 180degree sweep. In sharp contrast, Kerala is visible only as a thin, green strip of land. Malayalis, as the people of Kerala are called, rarely have a panorama of their beautiful land since the hills and vegetation obstruct their vision.

Inside the village of Ramakkal Medu, if visitors want to purchase something, a local will direct them to Balan Pilla "city". And of course, they find at the dead end of a road, Balan Pilla's lone tea stall, with a shop that can serve any consumer's need.

There is another village called Kumbanad on the pilgrimage route to Sabarimala, one of the most popular worship spots in Kerala. Again a remote village, just a 2-kilometre stretch. Yet, in this brief length, there are 16 banks. A survey conducted by a newspaper in 1998 revealed that more than 200 people have invested in excess of one crore rupees as fixed deposits in these banks. Kumbanad also has well-established schools, hospitals, and shops along with churches and Bible study centres. At least one member from every house is in the US or Europe, West or East Asia.

Kerala is 38,863 square kilometres of tropical land in the southwest tip of the Indian subcontinent. With average annual rainfall of 3,125 millimetres, its flora and fauna are rich and diverse; such intense inundation also creates 44 rivers and two major backwater systems, the Vembanadu, the biggest water body in western India, and the Ashtamudi. This state accounts for 1.18 per cent of India's total landmass and 3.34 per cent of the national population. The population density in the state is 819 people per square kilometre. However, actual population density is much higher since Kerala's land includes protected forest (25 per cent of the total), water bodies, and plantations that are virtually uninhabited.

The disposition of Kerala's urban spaces and economy makes it difficult to define and distinguish cities, towns, and villages using conventional categories. In other parts of India, urbanization is resulting in increased population growth in existing cities. In Kerala, a different phenomenon is observed. Seventy-five per cent of the population continues to reside in villages, slightly higher than the national average, and these villages are becoming townships with augmented facilities. Most of Kerala, except for remote places, is urban with banks, schools, shops, hospitals, and public utilities. Except for Ernakulam, where population growth and urbanization are simultaneous, Kerala's established towns are also globalizing without huge shifts in habitation. Many of these towns and villages indeed have become satellites of international metros. Kerala's social and political orientation has promoted a huge investment in education, which has created the most literate population in India and a large pool of skilled workers. However, the demand for their skills is much lower than the supply. Kerala's surplus human resources thus have spread all over the world seeking job opportunities. In this context, it is interesting to note that in 2004, a sum of Rs 18,460 crore was remitted to Kerala from abroad, which is seven times what the state receives as its share from the Central government's annual budget.

The even distribution of infrastructure along with availability of capital and water near the soil surface have contributed to Kerala's peculiar urbanization, in which the historical pattern of habitation in contiguous but individually owned homesteads persists and flourishes even as the state urbanizes. People do not need to cluster around the larger centres for the advantage of availability of services and resources. A well-established road network allows even smaller villages to remain connected with each other and larger towns. Kerala has 1,54,679 kilometres of road with a density of 4 kilometres per square kilometre, far ahead of the national average of 0.74 kilometre per square kilometre. For every 1,000 people, there are 4.86 kilometres of road, much higher than the national average of 2.6 kilometres. The distribution of road management is decentred: panchayats control 67 per cent of the road network, the state Public Works Department 17.02 per cent, and corporations and municipalities 10.08 per cent. The National Highway is just 0.98 per cent of the total. The remaining 4.02 per cent is maintained by the Irrigation and Forestry departments, the Electricity Board, and Railways. All these roads have made Kerala a supremely comfortable space for the transaction of commodities and services. People use the network to make small trips to access services in the various commercial centres that accrete around major junctions. This accessibility of infrastructure and connectivity has created a sense of unity among the state's residents.

The Past to the Present

Once soft, unpaved, foot-wide paths connected this land, along which people lived separated from each other by caste. These narrow pathways were violent corridors of debate such as who should walk in front, who should not walk at all, etc. Highly oppressive social stigmas and a crude but detailed practice of hierarchies split people into hundreds of castes. This alone, however, is not Kerala's past. In its collective memory, there are many narratives and layers and among them is one about Onam, the regional festival. Onam is a remembrance about how people lived as one during the reign of Mahabali, the Asura ("non-divine") king. For many centuries, the people of Kerala have been celebrating this festival.

There is historical evidence that Kerala's coasts were emporia for regular overseas trade. The coinage that Bowed in through this trade was hoarded, perhaps because people had no other use for it. Kerala existed as bits and pieces, often ruled simultaneously by several kings, hundreds of chieftains, and autonomous sanctuaries of a thousand places of worship. The oldest creation myth speaks of a saint who reclaimed from the sea and divided into villages a landmass named Kerala, imagined to stretch from Kanyakumari to Gokarna and isolated from the rest of the subcontinent. Old memories about Keralas borders are vividly marked in such myths.

Another layer of Kerala history begins from Marthandavarma's period 0729-58 CE). This king of Venad, a tiny kingdom in the southern tip of the Indian peninsula, extended his state up to the middle of present-day Kerala and formed Travancore by raising an army of local people. He then modernized and centralized it; Marthandavarma appointed the Dutch caprain De Lannoy, whom he captured in a war, as commander-in-chief and gave him the status of a local noble. The large size of Travancore as well as the creation of a centralized army was a new era in Kerala's statecraft. In 1750, Marthandavarma dedicated the state to his deity Padmanabha through an offering ritual called Trippadidanam and positioned himself and his successors as servants of the god. From this action, Travancore's residents came to see themselves as the subjects of a deity rather than as subjects of a mortal king. The idea of communally owned capital, a powerful social belief even in present-day Kerala, is also rooted in this event. In 1780, the small principality Perumpadappu became the much bigger state of Kochi under King Shakthan because he gained the support of Travancore to annex smaller chieftainships and accepted the over lordship of Hyder Ali of Mysore. Already by 1766, the Mysore sultan controlled the northern Malabar region. These events changed Kerala from tiny principalities to a set of large states, administered by a new class of bureaucrats and centralized armies. Later the princely states of Travancore and Cochin invested a great deal in the education, health, and well-being of their people as well as knowledge transfer from Europe. They paid high prices for access to modern engineering and transportation technologies, which they used within the limits of existing systems of caste and religion. Later, after Tipu Sultan’s Malabar came under British governance. British Malabar provided models for caste-fee, civil society that highly inspired Kerala’ evolution.

Modern-day Kerala is the result of the unification of the three regions: the princely states of Travancore and Kochi and the Malabar region of the Madras Presidency. After Independence, the Tamil-speaking southern parts of Travancore and Kannada-speaking northern pans of Mala bar were subtracted, and Palakkad from Madras state was added. Kerala's formation as a linguistic state was in 1956, on the 1st of November. The Malayalam language, rather than geography or history, forms modern Kerala's identity. Malayalam is a mixture of an old dialect of Tamil spoken in early historical Kerala and Sanskrit; it evolved over the last few centuries, enriched by words from Arabic, Persian, Portuguese, a by product of trade. An earlier form of the language first appeared in the Vazhapalli inscriptions in 830 CE and the Malayalam script began its evolution in the early 13th century. The grammar and aesthetic guidelines for this composite language and its verse and prose expressions are discussed in Leelatilakam, a 14thcentury manual. Ezhutachan, towards the end of the 16th century, wrote independent translations of Indian epics. The poetic expression in his verses contains a fully evolved language with its own grammar, very close to today's written and spoken Malayalam.

Around the mid-19th century, with Christian missionary activities, the language further improved and became a tool for modern education. The Jesuit priest Benjamin Bailey at Kottayam established the first printing press in Kerala in 1821. He published the first English-Malayalam dictionary in 1846 and the first Malayalam Bible in 1841. By the end of the century, printing and publishing became widespread; newspapers, novels, essays, and poetry analysed and criticized everyday life. There was an informal dissemination of modern education as ordinary people started imbibing these written ideas. It helped reformists and their movements challenge casteism and raise the discourse of human rights. For example, Narayanan (1854-1928, popularly known as Sri Narayana Guru), the philosopher and social reformer, addressed a self in the process of individuation, rather than an amorphous sense of personhood based on the longstanding practice of loyalty. As a modern person, he used straightforward, slogan-like phrases: be powerful by being organized and be enlightened with education. Even his poetry imagines God's divinity as a steamship, which can help navigate the mighty ocean of life. This is an example of imagination developing according to changing conditions.

The reform movements in Kerala were primarily in response to the crudity of Hindu casteism. The temple entry proclamation occurred in Travancore in 1935 and in one sense, officially ended discrimination among Hindus. Gradually temples in Kochi and Malabar too opened their doors to all castes. This tempered intra religious hierarchies among Hindus and made their communities similar to the less stratified ones of the Christians and Muslims. Perhaps, Kerala began evolving a new identity around this time, as a region where all three major religious communities had equal social rights.'

Along with this social reformation began a process of reconstruction of the notion of self, aided by widespread political movements, which led people towards a rational politics and the questioning of institutions. The role of communism is notable in all this.

Through their mass revolts, communist movements questioned the conservatism of tenant-landowner and employee-employer relationships.

Contents

| Foreword | 9 |

| Introduction | 12 |

| Thiruvananthapuram / City of a Horizontal God | 28 |

| Kollam / Urbanization in Tourism's Own Landscape | 42 |

| Alapuzha / A Hidden Fortress Made of Water | 60 |

| Kottayam / The Hills Are Moist | 78 |

| Kochi / The Other City | 88 |

| Thrissur / Round and Around the Town | 104 |

| Palakkad / Some Threads Including the Sacred | 118 |

| Kozhikode / Yesterday and Today | 132 |

| Kannur / Monumental, Monolithic | 146 |