Crosses Christian and Otherwise (Their Form and Meaning)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAH339 |

| Author: | Fredrick W. Bunce |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2014 |

| ISBN: | 9788124607374 |

| Pages: | 230 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.5 inch x 8.5 inch |

| Weight | 1 kg |

Book Description

About the Book

In “top-of-the-mind” reading, er iconographic representation of Christianity, though cross became an embodiment of Christian iconography only after the fifth century CE. In this volume, the author unveils the existence of 500 plus crosses, of which around 300 are of ecclesiastical, heraldic or mundane crosses. Most of these cruciforms were introduced before the twentieth century.

Cruciform was antecedent of Christianity. There were numerous cruciform Hindu and Buddhist temples, even before the advent of Christianity and thus these hold no Christian ecclesiastical relevance. Of late many churches, cathedrals and basilicas applied cruciform to their structure and look in conformity with the Christian iconography. This enunciates the endless design possibilities of cruciform. The book discusses the pre-Christian iconographic cruciform Hindu and Buddhist temple structures and in detail the Christian cross iconography and the varied types of crosses. It delves deep into the numerous forms of Latin and Greek crosses, mainly from the ecclesiastical and heraldic viewpoint. Crosses adorned ecclesiastical, military, professional and trade implications, and were carved on shields and coats of arms.

This volume also addresses other categories of crosses such as solar crosses, saltire crosses and miscellaneous crosses though they too have occasional ecclesiastical and heraldic implications. The book thus gives a fair account of the emergence, use and application of cruciforms until the twentieth century.

About the Author

Fredrick W. Bunce, a PhD and a cultural historian of international eminence, is an authority on ancient iconography and Buddhist arts. He has been honoured with prestigious awards/commendations and is listed in Who’s Who in American Art and The International Biographical Dictionary, 1980. He is currently Professor Emeritus of Art, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, Indiana. He has authored the following books, all published by D.K. Printworld:

Preface

While doing research for a manuscript entitled Cruciform, Circular and Apsidal Temple Plans in India: Genesis and Iconography, I attempted to make certain parallels between obvious cruciform Indian temples and the various cross forms encountered in Christian iconography. In preparing an Appendix, I was faced with a number of sources, primarily on the Internet, which listed and/ or illustrated scores of cross forms. Without exception, they stated that there were 200 or 300 different ecclesiastical and heraldic or mundane crosses. But, at best, the various sites, each illustrated separately approximately 100 crosses, give or take a few.

What about the other hundred or so forms? This sent me searching various sites and sources in the attempt to identify the myriad cruciforms just out of interest. Not only was the search, the research one of the most intriguing parts of the project, but also the redrawing of the various crosses using Adobe PageMaker 6.0 offered many challenges. The result was an amassing of over 500 crosses and their variations many of which fell outside the 1/200 or 300 different ecclesiastical and heraldic or mundane crosses”, noted above. The vast majority of the crosses found were used prior to the twentieth century. The possibilities of cruciform designs are endless. Therefore, contemporary cruciforms- i.e. twentieth- and twenty-first-century designs - were, for the most part, not considered with a few exceptions.

Introduction

Few symbols, few iconographs in the world are more recognizable than the cross. It is seen primarily as a Christian symbol, and its form is recognized by most of the world’s population as a symbol of that faith. However, a number of the types of crosses or cross forms, predate the Common Era, and, therefore, Christianity - e.g. the Ansata Cross, the Fylfot Cross and the Solar Cross. Some cruciforms have developed outside the Christian bounds and have later been adapted by that faith.

In ancient times, the cross was a symbol worn by the Assyrian kings Sansirauman as well as Ashumasirpal as a sign of their majesty, dominance and supremacy. The Persian tombs of Cyrus, Xerxes and Darius have a cruciform element cut into the exterior. The Greek goddess Artemesia (Diana) was shown with a cross behind her head. Numerous crosses are seen in Meso- and South America prior to the European invasions. The popular Celtic Crossis certainly pre-Christian and many scholars believe that it represented the axis mundi and is related to the Norse sun wheel.

The common term” cross” may have come from the Old or e word kross or the Old Irish - i.e. Gaelic/Celtic - cros. Both kross and cros are obviously derived from the Latin word crux. However, it is interesting to note that the Old English term for what we now call cross was rod or rood and referred to a crucifix - i.e. a cross upon which hung the body of Jesus Christ. The term rood is still applied to that physical division, the visual barrier between the nave and the sanctuary of an English church or cathedral- i.e. the rood-screen - upon which is mounted a cross or crucifix. Rood is related to the Dutch word of the same meaning, roede as well as the German rute which denotes a rod and/or a crucifix. In this sense - i.e. rod, rood, roede, rute - may be closer to the act of execution as early forms of crucifixion merely employed a tree trunk or beam or post upon which the hapless victim was hung.

The New Testament states that the Christ was “hung on a tree” (Acts 5:30, 10:39, 13:29; Galatians 3:13 and I Peter 2:24). This may have been an unproductive tree (arbor infelix) thought only suitable for execution of criminals. Or the victim may have been tied to a beam (patibulum) which was raised and affixed to a tree (arbor infelix) or post (crux composita or crux acuta). The term “cross” also appears often in the New Testament - e.g. I Corinthians 1:17; Galatians 2:19 and Philipians 3:18. The question of “tree” or “cross” is a conundrum not pursued here.

The Latin crux is related and applied to the term(s) for torture - i.e. cruciamentum or cruciatus. The term “crucifixion” is a means of execution or torture upon a crux. Indeed the terms for torture and cross were related to crucifixion which was a slow and tortuous means of punishment and ultimately death that was practised in the ancient world. Some see the term “cross” as related to the name “Christ”. This is erroneous as it is clearly related to the term cruciamentum or cruciatus.

Crucifixion is essentially a passive form of torture and/ or execution - i.e. the victim is affixed to a cross (crux immissa or crux commissa) or pole (crux simplex) either by ropes or nails and left to die. Other than the attaching the victim to the cross, no other form of punishment or physical violation was generally employed. Frequently, it is believed that only the hands or arms were secured and the feet left free. This would have been the quicker form of execution as the weight of the body would quickly weaken the muscles, particularly of the diaphragm, and ultimately cause suffocation. If, on the other hand, the feet were also secured, they would have provided enough support and the advent of death would have been much slower. This form of crucifixion would have ultimately caused death by dehydration, the subsequent shutting down of vital bodily functions, and/ or suffocation.

If nails, rather than ropes or some other tether, were used, it is almost certain that the nails were placed just above the wrist rather than through the palm of the hand as is frequently depicted in paintings of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. This is particularly true if only the hands or arms were secured. If the nails were placed through the palms of the hand alone, the tendons and muscles are so aligned that weight of the body would cause the victim to ultimately tear loose and fall. However, if the feet, too, were nailed, then the legs would have to be flexed at the knee to allow the nails to pierce the foot, or a canted footrest would have to be affixed to the upright so that the nailing might be accommodated. The use of nails through the feet would have been an extra form of torture and pain and would have extended the agony. In Christian art the crucifixion is depicted with the nails through the palms of the hand and the feet are nailed either separately or together - i.e. a four-nail or a three-nail crucifixion.

This symbol that we now universally recognize - i.e. the cross - was not accepted by the Early Christians as a symbol of their faith. The cross was to them a most odious symbol, a repugnant sign connected with death and torture much in the same way that a gibbet or an electric chair might be considered today. As such the Early Christians were loath to depict the crucifixion on any form. In addition, it was not until after the fifth-century that the divinity, crucifixion and resurrection of the Christ was promulgated and almost universally accepted. The pre-eminent symbol accepted and used by the Early Christians was the fish (Figure 1). It was not until the fourth century that Constantine’s Labarum, the Chi Rho, came into use. We may view the Chi Rho or Labarum as a cruciform, but, its initial use was as a representation of the first letters of Christus (Chi) Rex (Rho) - Christ King. The appearance of the cross (crux) as we know it followed in the next century.

Contents

| Preface | v |

| List of Figures | ix |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Christian Cross Iconography | 2 |

| Types of Crosses | 4 |

| Christian Cruciform Churches | 5 |

| Hindu and Buddhist Cruciform Temples | 6 |

| Coats of Arms | 10 |

| Shields | 12 |

| Ecclesiastical Implications | 14 |

| Crosses with Militaristic Implications | 15 |

| Crosses with Professional or Trade Implications | 15 |

| Scope | 15 |

| Crux Simplex and Tau Crosses | 18 |

| Militaristic Tau Crosses | 23 |

| Latin Crosses | 24 |

| Ankh and Chi Rho Variation | 30 |

| Pommee and Botonee Variation | 33 |

| Byzantine, Manx and Coptic Variation | 37 |

| Potent and Crosslet Variation | 40 |

| Moline, Recercelee, Fleuree Variation | 41 |

| Annuleted Variation | 44 |

| Rope Variation | 46 |

| Miscellaneous Variation | 47 |

| Processional Variation | 56 |

| Double Crosspiece Variation | 60 |

| Militaristic Variation | 69 |

| Triple Crosspiece Variation | 70 |

| Militaristic Variation | 74 |

| Fitchy Variation | 77 |

| Greek Crosses | 83 |

| Surface Variation | 86 |

| Crosslet/Potence Variation | 89 |

| Coptic Variation | 92 |

| Interlaced Variation | 95 |

| Gammadia Variation | 99 |

| Boton/Pomme Variation | 101 |

| Annuleted Variation | 104 |

| Pattee and Patonce Variation | 108 |

| Star /Flame Variation | 112 |

| Jerusalem Variation | 115 |

| Plant/ Animal Variation | 118 |

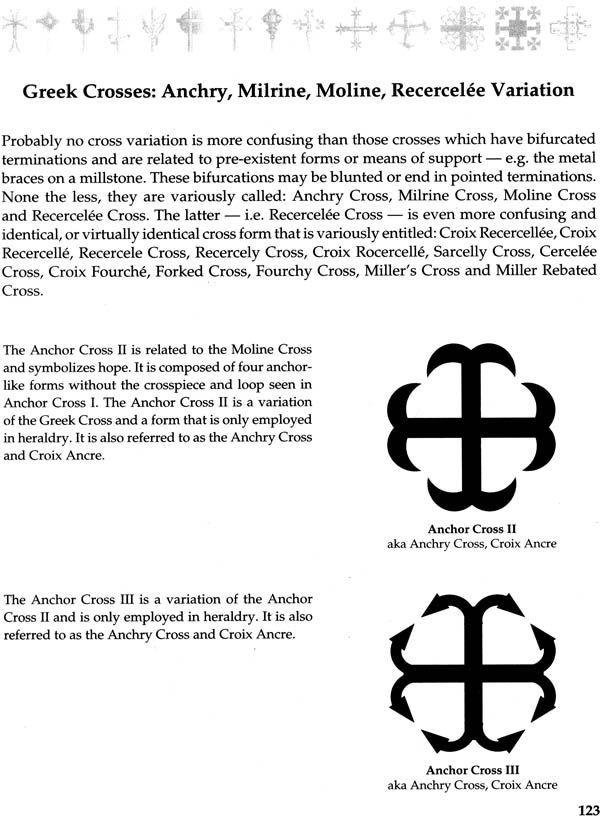

| Anchry, Milrine, Moline, Recercelee Variation | 123 |

| Greek Crosses: Militaristic Variation | 129 |

| Fleur-de-lys Variation | 135 |

| Fitchy Variation | 138 |

| Maltese Variation | 145 |

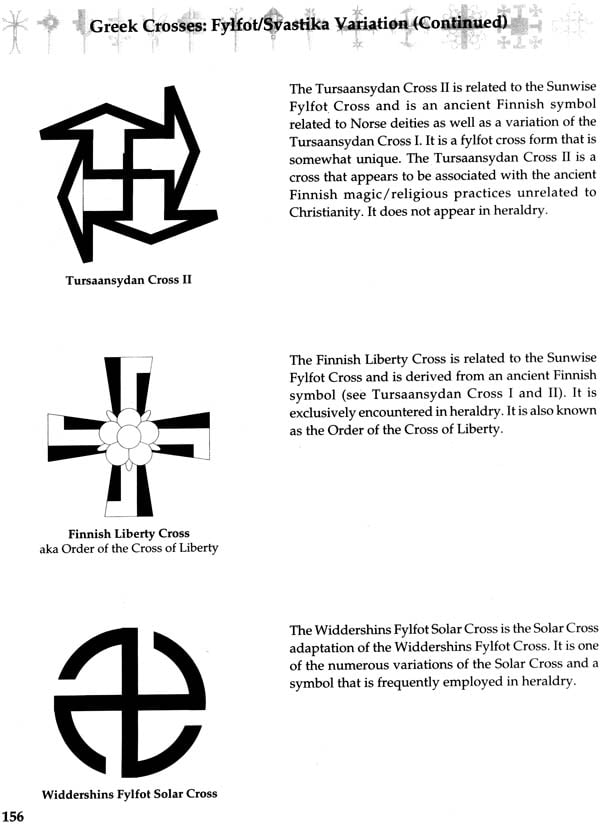

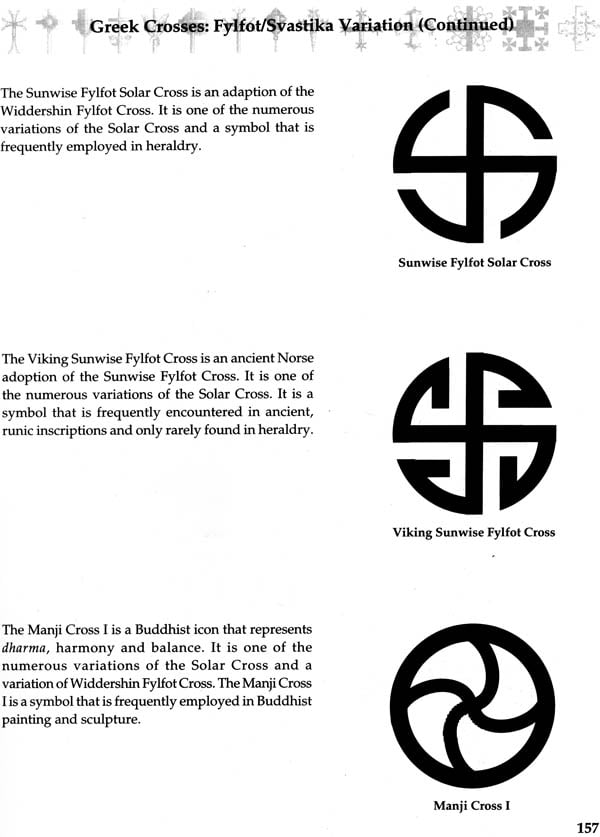

| Fylfot/Svastika Variation | 150 |

| Miscellaneous Variation | 161 |

| Solar Crosses | 176 |

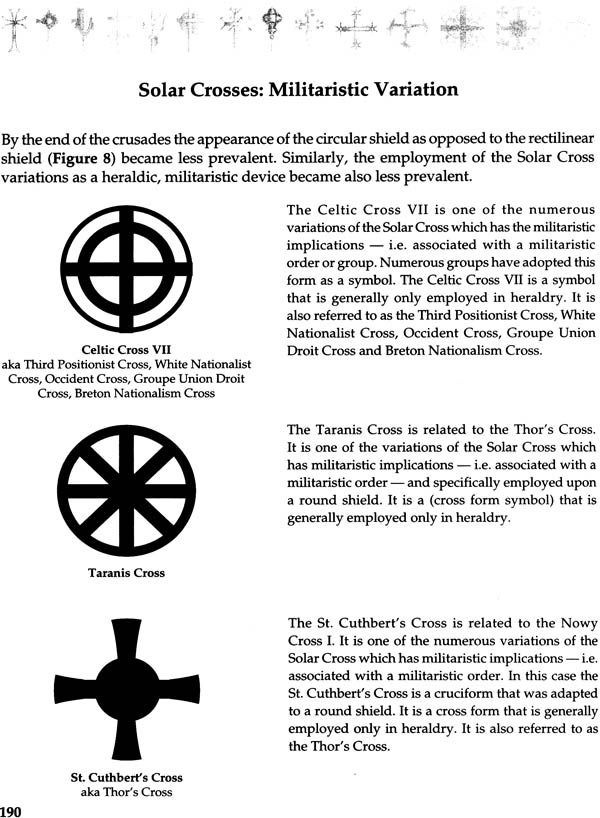

| Militaristic Solar Crosses | 190 |

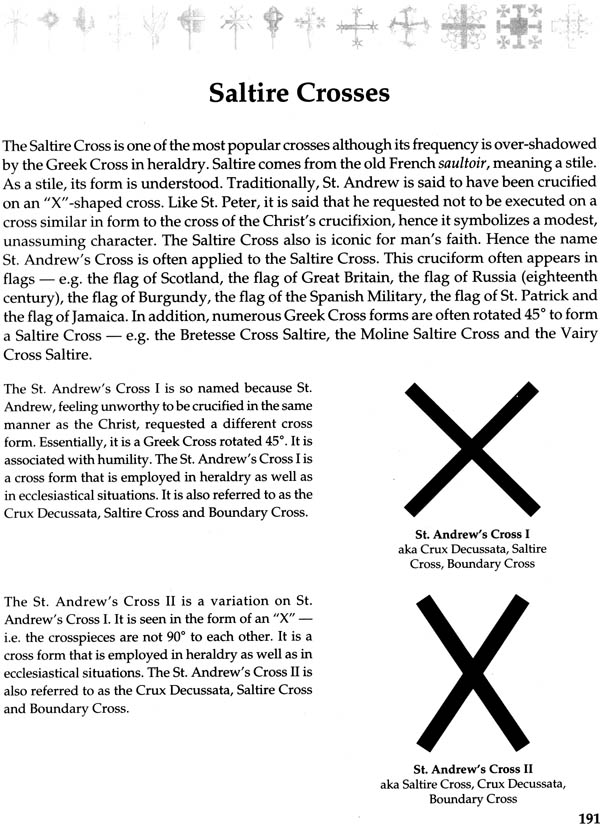

| Saltire Crosses | 191 |

| Baptismal Variation | 201 |

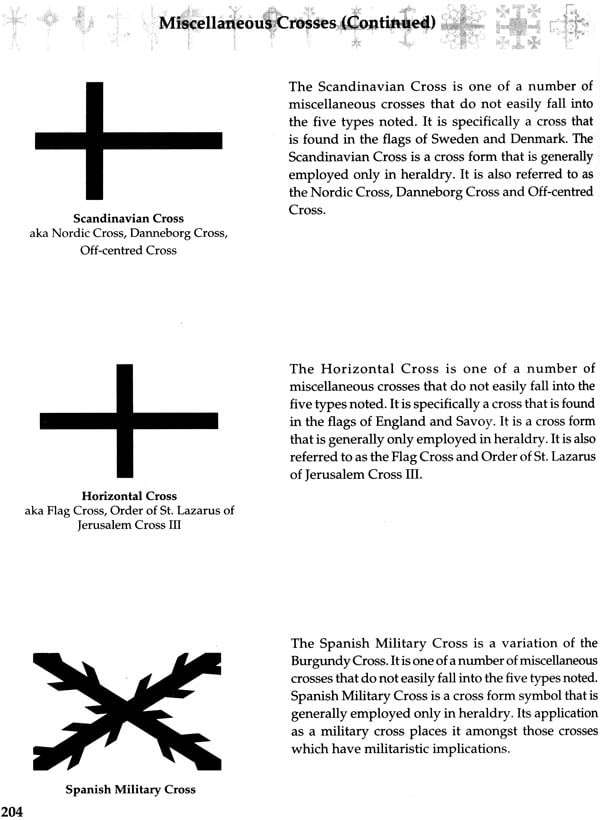

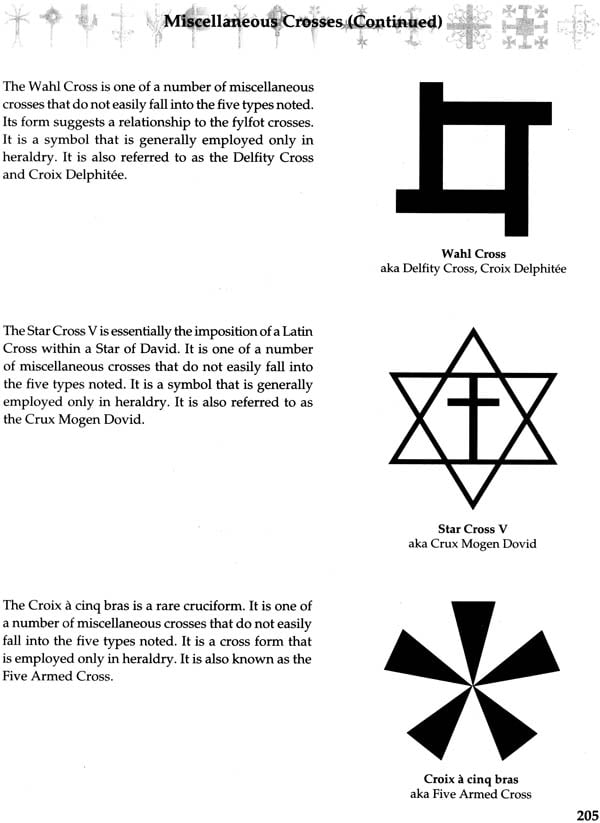

| Miscellaneous Crosses | 203 |

| Coloured Crosses | 208 |

| Resources | 209 |

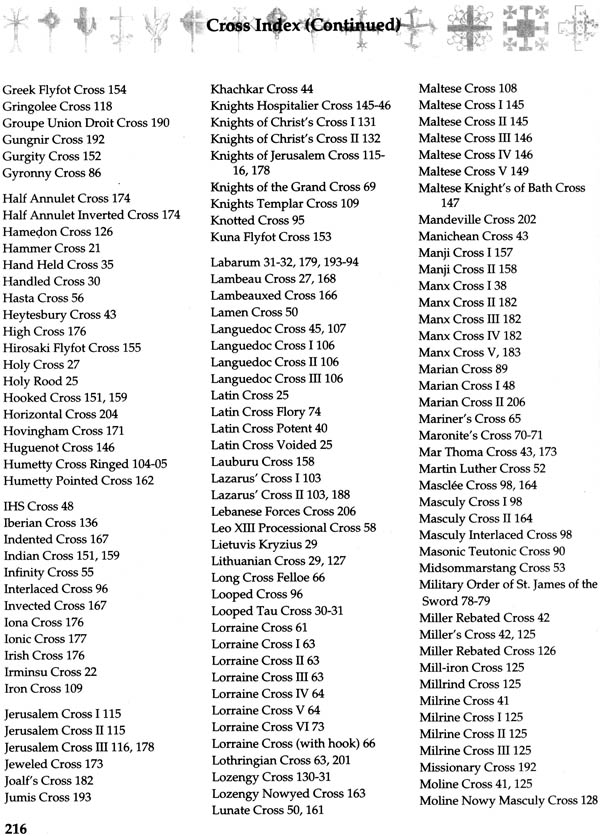

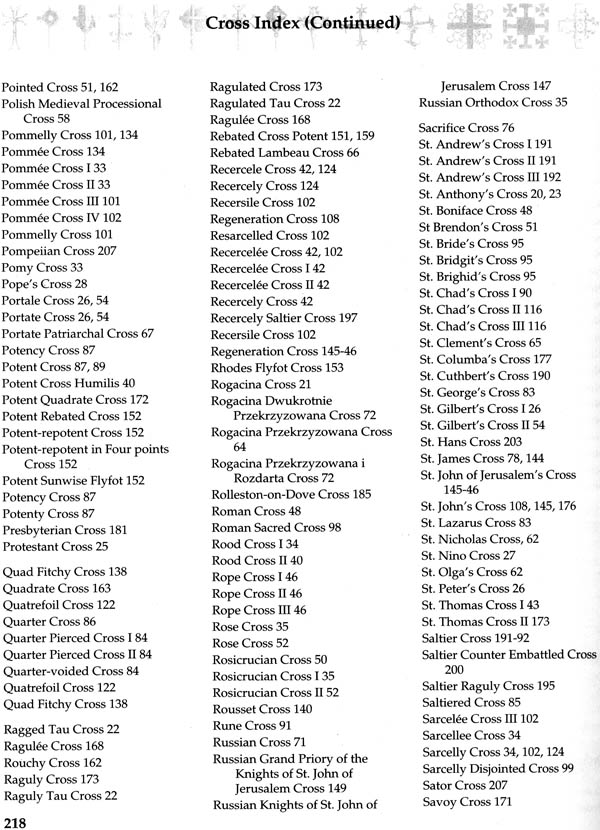

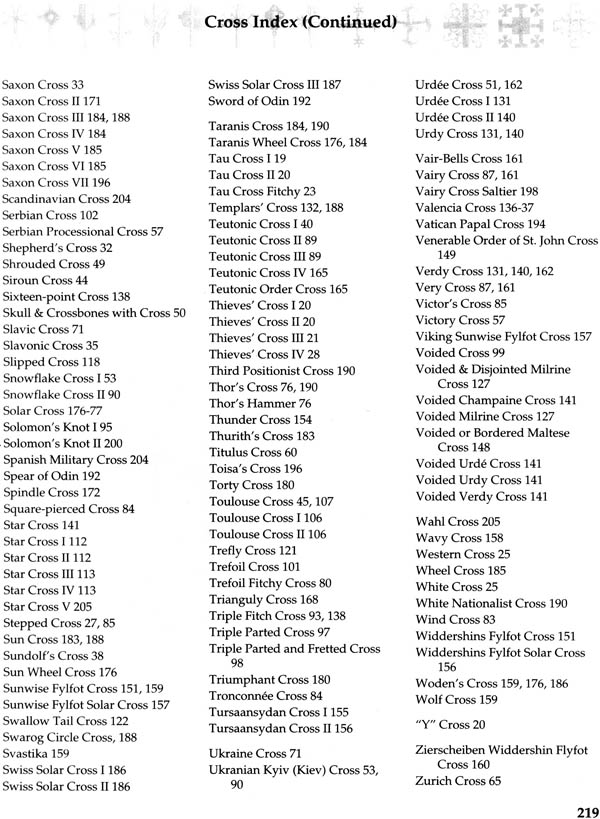

| Cross Index | 213 |