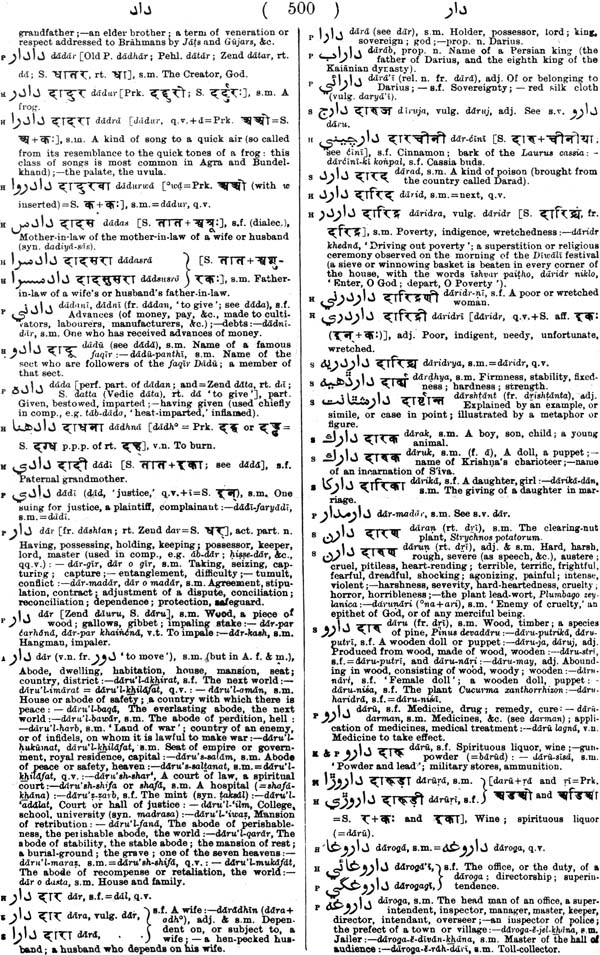

A Dictionary of Urdu Classical Hindi and English

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAM951 |

| Author: | John T. Platts |

| Publisher: | Manohar Publishers and Distributors |

| Language: | Urdu, Hindi and English |

| Edition: | 2006 |

| ISBN: | 9788173046704 |

| Pages: | 1270 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 10.0 inch X 7.0 inch |

| Weight | 1.80 kg |

Book Description

The distinguishing features of this classic dictionary are: the space assigned to the etymology of words; the arrangement of words which are similarly spelt but differently derived into separate paragraphs according to their etymology; the indicating the postposition by means of which an indirectly transitive, or an intransitive verb governs its object, and the change of meaning which frequently takes place by the employment of different postpositions after a verb (many verbs, in existing dictionaries, are given as transitive, thus leading one to suppose that they govern the accusative case, whereas they govern, it may be, the genitive, or the ablative, or the locative; e.g. qabza karna is called a transitive verb, although it governs the locative); the admission of numerous words which do not find place in the literary language.

This volume is an invaluable accessory for the scholars of classical Urdu and Hindi.

John Thompson Platts (1830-1904) was born in Kolkata. He became head of Saugor School in 1859 and headmaster of Benares College in 1861. After his retirement from India, Platt was elected teacher of Persian at Oxford University in 1880. He wrote works on the grammar of Hindustani and Persian and compiled a number of dictionaries of Asian languages.

A NEW Dictionary of Urdu and Hindi will not, I believe, be deemed an unnecessary work by those who have studied or taught those languages with the aid of the existing Dictionaries. The Dictionary of Forbes is-to say nothing more unfavourable of it considerably behind the age. The growth and expansion of Urdu and Hindi have gone on with unabated rapidity since the publication of that work; and words and phrases and meanings of words by thousands will be sought in it in vain. The Hindi Dictionary of Bate is a useful work for students of Hindi; but it is of no use to students of Urdu, although it contains a great part of Forbes’s work. It is compiled, moreover, on the plan of, and reproduces nearly all that is faulty in, the Dictionary of Forbes. Sanskrit, Hindi, Persian, and Arabic words, that have not the slightest connection either in meaning or etymology are, not infrequently, placed together in the ‘same paragraph, without any attempt to discriminate between them, simply because they happen to be spelt with the same letters and to have the same pronunciation. On the derivation of words and grammatical forms, Bate’s Dictionary furnishes little or no information. The Hindustani Dictionary of Fallon aims at a special object, distinct from that pursued in the pages of t his work: it aims, rather, at the collection of a particular class of words and phrases. Hundreds of words that occur in Hindi and Urdu literature Dr. Fallon thought proper to give no place to in his Dictionary, because, from his point of view, they were pedantic. This must, necessarily, considerably diminish the usefulness of his’ book so far as students are concerned. The work is, notwithstanding, one of considerable merit, and will, no doubt, be valued by scholars on account of the numerous proverbs and quotations from the poets which it contains.

In the preparation of the work now offered to the public I have availed myself of the labours of my predecessors. I can affirm, however, with confidence, that I have not followed them blindly. I believe the work will be found to be something more than a “mere compilation”: that, in fact, as regards both matter and form, it will be allowed to have some claim to originality; and that the changes introduced, and the additions made to the vocabulary, are so numerous and extensive that it may justly claim to be considered as substantially a new work. The fact is, I have for many years been engaged in the study of Urdu and Hindi books (in prose and verse) and newspapers with the view of collecting words and phrases for this work. I have thus been enabled, not only to verify most of the words given in the Dictionaries of Shakes pear and others, but to supplement them with thousands of new words and phrases and additional meanings of words. Moreover, a long residence in India made me acquainted with much of the living colloquial language not found in Dictionaries, which I was careful to note.

The plan of the work resembles in many of its features that of Shakespeare’s Dictionary. Where, however, a number of words come by accident to be spelt in the same way, but have very different meanings, and are derived from very different sources, I have, when able to do so, placed them in separate paragraphs, according .to their etymology, and rot jumbled them together under one head, as is done by Shakespeare and other lexicographers. In the case of compound words and phrases I have followed Forbes in using the Roman character alone.

The distinguishing features of the work are: 1 ° The space assigned to the etymology of words; 2° The arrangement of words which are similarly spelt but differently derived into separate paragraphs according to their etymology (as mentioned in the preceding paragraph); 3° The indicating the postposition by means of which an indirectly transitive, or an intransitive verb governs its object, and the change of meaning which frequently takes place by the employment of different post positions after a verb. (Many verbs, in existing Dictionaries, are given as transitive, thus leading one to suppose that they govern the accusative case. whereas they govern, it may be, the genitive, or the ablative, or the locative; e.g. qabza karna is called a transitive verb, although it governs the locative.) 4° The admission of numerous words which do not find place in the literary language.