Hindu Womanhood

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAH254 |

| Author: | Sadhu Mukundcharandas |

| Publisher: | Swaminarayan Aksharpith Publications |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| ISBN: | 9788175263444 |

| Pages: | 288 (32 Color and 40 BW Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 330 gm |

Book Description

Preface

The annals of Indian history abound with biographies of brave and powerful Hindu women, each conjuring images of tremendous valour and virtue that have inevitably shaped Indian womanhood. Each have looked to the eternal principles of Sanatan Hindu Dharma to guide their thoughts, actions, character and hence their destiny.

The Katyayan Srauta Sutra (1.1.7) describes a woman superior than a man - Stri chavisheshat. The ancient lawgiver, Manu considers a mother as excelling a thousand fathers (Manu Smriti 2/145). As a wife, she is considered a sahadharmini - an equal spiritual partner, to the extent that all spiritual rituals by married men were considered fruitless unless accompanied by their wives. Panini, the Sanskrit grammarian gives the etymological meaning of the word patni (wife) as, “One who participates in the religious rituals of her husband.”

The concept of “women’s equality to men” is easily misconstrued as a newly evolved (Western) theme, when it is in truth no more than a ‘diluted’ version of a much higher spiritual status accorded to women by Hindu shastras.

It is therefore essential to introduce ourselves to the fundamental potential of every female birth, by exploring the rich heritage of extraordinary women-heroines who embodied the essence of “Hindu womanhood”. Ancient Hindu shastras and rishis are uncompromising in emphasising the importance of every woman’s elevated stature, role and responsibility in a thriving community.

In his three volumes on Bharatni Devio, the author Shivaprasad Pundit describes the stories of 528 great women of India. In the same spirit, this book; Hindu Womanhood brings to the reader a select 51 stories that hope to illuminate the eternal ideals and facets of the womanhood of Sanatan Dharma. These virtues based on spirituality and not on the mundane realm of body-consciousness, still deeply inspire and enlighten millions of women in the Hindu world today. Most of the women in these stories have become household names all over the land for the lofty ideals they represented, such as chastity, fidelity, nurture of righteous samskaras (values) in their offspring, spiritual wisdom and unalloyed devotion to the Supreme Reality.

This book is divided into six parts.

Part One gives a glimpse of women with virtues of statesmanship and valour. The unfolding stories reveal queens who assumed the administration of their husband’s kingdoms after widowhood under challenging circumstances and queens who led their soldiers in battle, fighting as chivalrously as the men.

Part Two introduces the stories of mothers such as Madalsa, Mainavati, Jijabai, Kanubai and Diwaliba.

Part Three discusses stories of Satis - women, whether widowed or married, who dedicated themselves totally to attain Paramatma.

Pativratas were women who strictly maintained their chastity. If males other than their husbands demanded their hand by force, as was the case for Jasma, Pad mini and Ranakdevi, they chose to die rather than be defiled. The young and still-to-be-married sisters, Tana and Riri Mehta, who were pupils of the famous musician Tansen (whose life the sisters once saved), showed great courage when they protected their purity (satitva) by choosing to drown themselves on the verge of being kidnapped by lewd Mogul generals.

Part Four relates the stories of two famous Brahmavadinis, Gargi and Maitreyi, who among the many Brahmavadinis excelled in the same manner as the rishis in studying the Vedas and other texts in the quest to realise Paramatma. Brahmavad means to strive to realise Paramatma. This is followed by a discussion about Brahmavadinis and later women scholars. The rishikas of Sanatan Dharma reflect the excellence of female scholarship during the Vedic period and the equal opportunity available to them to study sacred texts, the only occurrence of its kind in the whole of the ancient world.

Part Five relates the stories of devotees and mystics who offered sublime devotion to Paramatma. For the Gopis, Paramatma manifested in human form as Shri Krishna. Five millennia later, Mirabai, Andal, Gauribai and Ganga Sati offered devotion to him through his murti (image) by composing and singing bhajans that exemplify his glory and capture his divine pastimes. Their profound bhajans are still popular in Hindu homes and resound in the domes of mandirs throughout the world. Sarada Devi offered devotion to her living deity Sri Ramakrishna and served him as such. Anandmayi Ma sang bhajans in the quest to realise Kheyal - the One within. Both mystics shipped into trance-like states when engrossed in devotion or kirtan - in the case of Anandmayi Ma.

Part Six is an account of remarkable women disciples from the time of Bhagwan Swaminarayan in the early 19th century. They depict similar features as those discussed in Part Five of the stories of women yearning to realise Paramatma, For the women disciples of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya, Paramatma manifested in human form as Bhagwan Swaminarayan. Therefore they could offer him devotion in a unique and exuberant manner during his 49-year lifespan. Many of these women were born siddhas - endowed with the power to attain samadhi due to their past samskaras and Bhagwan Swaminarayan’s grace. By this ability, they experienced his constant vision in their atmas and witnessed Bhagwan Swaminarayan’s daily activities wherever he travelled. Such enlightenment enabled them to teach from the Sampradaya’s texts and impart spiritual wisdom to many other women.

This sowed the seeds of spiritual education in illiterate women in early 19th century Gujarat. In spite of the low literacy amongst women, they certainly were not spiritually ignorant. By receiving spiritual wisdom from the stalwart elders, they too strived on the path of sadhana and realised Paramatma. Some were able to do this to such a degree, that having become spiritually enlightened, they possessed the ability to forsake their mortal frames at will and attain Akshardham, Bhagwan Swaminarayan’s divine abode.

Many women of Sampradaya who realised the painful and binding nature of samsara, chose to renounce it and join the order of samkhya-yoginis. This was the name Bhagwan Swaminarayan gave for such women disciples, who either renounced mundane life or after being widowed, chose a simple life of austerities and lifelong devotion to Paramatma.

Parts 1 to 6 collectively depict the profound virtues embodied by the women of Bhararvarsh, such as statesmanship, valour, grit, purity, fidelity, simplicity, austerity, humility, teaching spiritual samskaras to their offspring and sublime devotion to the spiritual guru and Paramatma.

The Appendices provide details about various other aspects of womanhood of Sanatan Dharma.

Introduction

Although women’s education in generally began to decline in medieval India women of a royal lineage previously received training in warfare and administration. Some notable examples include queens such as Nayanika of the Satvahana dynasty (2nd century BCE), Prabhavati Gupta of the Vakataka family (4th century CE) - who ruled for ten years in the Central Province - and Vijayabhattarika, senior queen of King Chandraditya of the Chalukya dynasty, who ruled a part of the Bombay Deccan in the mid 7th century. They assumed the administration of their kingdoms while their sons were still young. The mother of King Udayana of Kausambi assumed administration when he was taken captive.

Some queens ruled as regents after their husbands died. The earliest reference to such a case is the queen of Masaga. She directed military operations against Alexander after her husband was killed in battle (circa 326 BCE). In the 10th century CE, the queens Sugandha and Didda ruled Kashmir after being widowed. Towards the end of the 13th century, during Mareo Polo’s visit, a queen governed the Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh in south India. When King Lalitabharanadeva died around the end of the 9th century in Orissa, his widowed queen agreed to rule at the behest of his ministers. Queen Tribhuvanadevi of Orissa also reigned independently.

Some Rajpur queens showed valour and statesmanship equal to their kings. When King Samarsinh died in battle along with King Prithviraj Chauhan in 1193 against Kutbuddin, Karmadevi, the former’s wife assumed charge and fought as the leader of her troops.

When Sultan Bahadur Shah of Gujarat attacked Chittor, one of the widows of Rana Sang, Karnavati defended the fort. With a fiery speech, she ignited the valour of the downhearted Rajputs, However, due to heavy odds, the gallant Rajputs succumbed. Meanwhile, Jawaharbai, another of Sang’s widows, who had assumed charge, fought alongside her soldiers and also died with them.

There were queens who ruled astutely and became famous for their statesmanship, courage, bravery and diplomacy. Queen Tarabai of Kolhapur, despite reigning over a small kingdom, gallantly organised a Maratha opposition against Aurangzeb, the Delhi Mogul, after her husband Rajaram’s death in 1700 CE. This counter attack was staged in the face of a tyrant who obviously possessed the biggest military force in India. Another queen, Anubai Ghorpade of Ichalkaranji, near Kolhapur, reigned efficiently for thirty years. She participated with her own soldiers in the military campaigns of the Peshwas.

Sembian Mahadevi was the queen of King Chola Gandaraditya I (950-957 CE). When the king died in a battle, she instated his brother on the throne while she assumed its administration. Similar to Ahalyabai, she dedicated the Chola kingdom to Paramatma. By this devotional paradigm the Chola Emperors became a dynasty of temple builders and religious socialists.

When King Dalpat Shah of the Gond dynasty died in 1550, his wife Rani Durgavati, managed the Gond kingdom, since their son Vir Narayan was only five years old. She fought and defeated Baz Bahadur, On 24 June 1564, she faced Akbar’s general, Asaf Khan. In this pitched battle, she and Vir defeated the Moghul army several times. Only when Khan brought heavy guns was she defeated. She was struck by an arrow in her neck. Rather than be taken a prisoner, she killed herself with a dagger. On 24 June 1988, the Madhya Pradesh government issued a postage stamp and renamed a university in her memory.

In the late 17th century, Belvadi Mallamma was the queen of Ishwar Prabhu, a chief of 360 villages in north Karnataka. When Chhatrapati Shivaji’s soldiers attacked the Belvadi fort, Ishwar Prabhu died. The queen then took over, fought and defended the fort for 27 days. Even a seasoned Maratha general such as Dadaji found her an invincible adversary. When supplies ran out, Mallamma opened the fort and fought like an enraged lioness.

Only when her right hand became paralysed and her horse was killed, did she accept defeat. When presented before Shivaji, he treated her graciously. “Mother”, he said with reverence, “I have not seen such bravery. Excuse me for what has happened.” He then returned all her villages and proclaimed her queen of Belvadi.

In the early 19th century, Queen Chennamma of Kittur, in north Karnataka, fought the British who wished to capture her dead husband’s kingdom, since he was childless. Successful initially, she was betrayed by some of her own soldiers. The British then imprisoned her at Bailhongal.

Kushalkunvarba was the queen of Maharana Somadeva, the Sisodia Rajput king of Dharampur state in south Gujarat. When Somadeva died in 1784, she served as regent until her son Rupdeva was old enough. However, at the age of 24, he also died, leaving a young son named Vijaydeva I. Once again, Queen Mother Kushalkunvarba governed efficiently into her old age (see chapter 39). Being religiously inclined, she invited Bhagwan Swaminarayan to Dharampur in 1816 to celebrate the Vasant festival.

The detailed stories of four queens are included in the following section: Veera, Karmadevi, Ahalyabai and Chennamma.

Contents

| Reviews | ix | |

| Preface | xvii | |

| Preface to the second edition | xxi | |

| Part 1 Stateswomen | ||

| Introduction | xxiii | |

| 1 | Veera (Queen of Chittor) | 1 |

| 2 | Karmadevi (Queen of Mewar) | 3 |

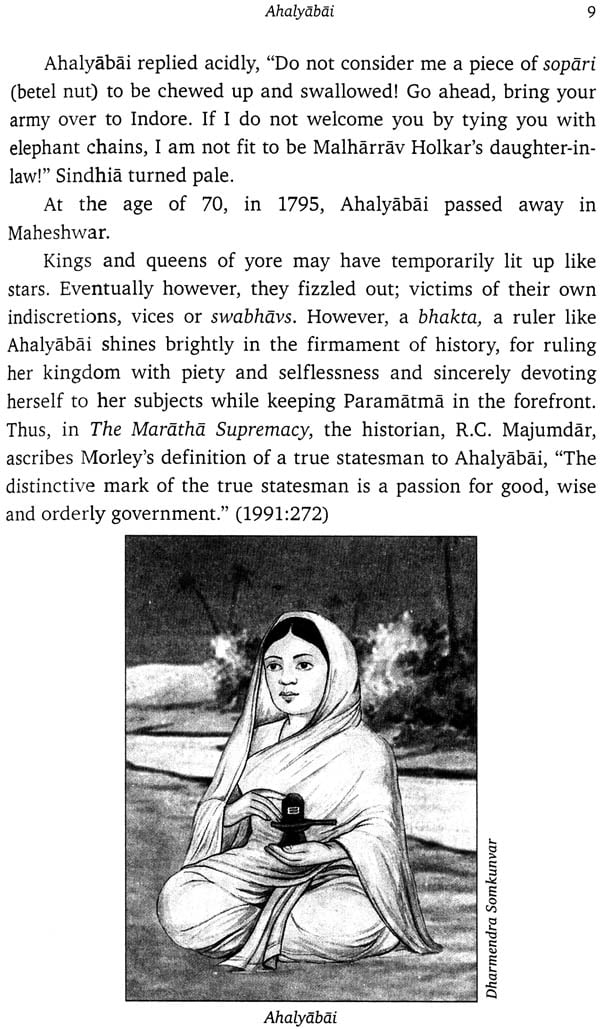

| 3 | Ahalyabai (Queen of Indore) | 5 |

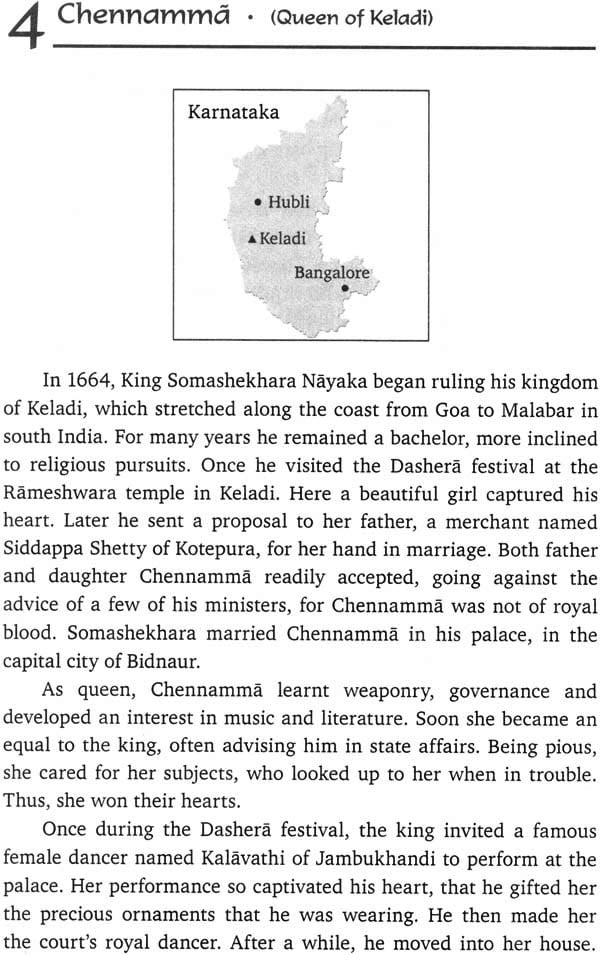

| 4 | Chennamma (Queen of Keladi) | 10 |

| 5 | Lakshmibai (Queen of Jhansi) | 16 |

| Part 2 Mothers | ||

| Introduction | 23 | |

| 6 | Sati Madalsa (King Rutadhwaj’s queen) | 25 |

| 7 | Mainavati (King Gopichand’s mother) | 27 |

| 8 | Jijabai (Queen mother of Shivaji) | 29 |

| 9 | Kanubai | 32 |

| 10 | Diwaliba (His Holiness Pramukh Swami Maharaj’s mother) | 35 |

| Part 3 Satis and pativYatds | ||

| Introduction | 39 | |

| 11 | Sita | 41 |

| 12 | Urmila | 48 |

| 13 | Shabari. | 50 |

| 14 | Sati Ansuya | 52 |

| 15 | Sati Savitri | 54 |

| 16 | Bhamti | 57 |

| 17 | Ranakdevi (Queen of Junagadh) | 58 |

| 18 | Jasma Odan | 61 |

| 19 | Chanchalkumari (Princess of Rupnagar) | 63 |

| 20 | Lalba (Queen of Bikaner) | 67 |

| 21 | Padmini (Queen of Chittor) | 69 |

| 22 | Tana and Riri Mehta | 73 |

| 23 | Rupali (The Garasni) | 74 |

| 24 | A Pativrata’s power in the 20th century | 78 |

| Part 4 Brahmavddinis and rishikds | ||

| Introduction | 81 | |

| 25 | Gargi | 82 |

| 26 | Maitreyi | 84 |

| 27 | Rishikas | 86 |

| Part 5 Devotees and mystics | ||

| Introduction | 93 | |

| 28 | Gopis | 96 |

| 29 | Mirabai (Queen of Chittor) | 102 |

| 30 | Andal (The female Alwar) | 108 |

| 31 | Gauribai | 112 |

| 32 | Ganga Sati | 116 |

| 33 | Janabai | 121 |

| 34 | Sri Saradamani Devi (The Holy Mother) | 125 |

| 35 | Nirmala Sundari (Sri Anandmayi Ma) | 133 |

| Part 6 Women devotees of the Swdmindrdyan Sampraddya | ||

| Introduction | 139 | |

| 36 | Bhaktimata (Bhagwan Swaminarayan’s mother) | 143 |

| 37 | Sakarba (Aksharbrahman Gunatitanand Swami’s mother) | 14R |

| 38 | Jaya and Lalita (Kathi princesses of Gadhada) | 153 |

| 39 | Kushalkunvarba (Queen Mother of Dharampur) | 163 |

| 40 | Rudibai | 169 |

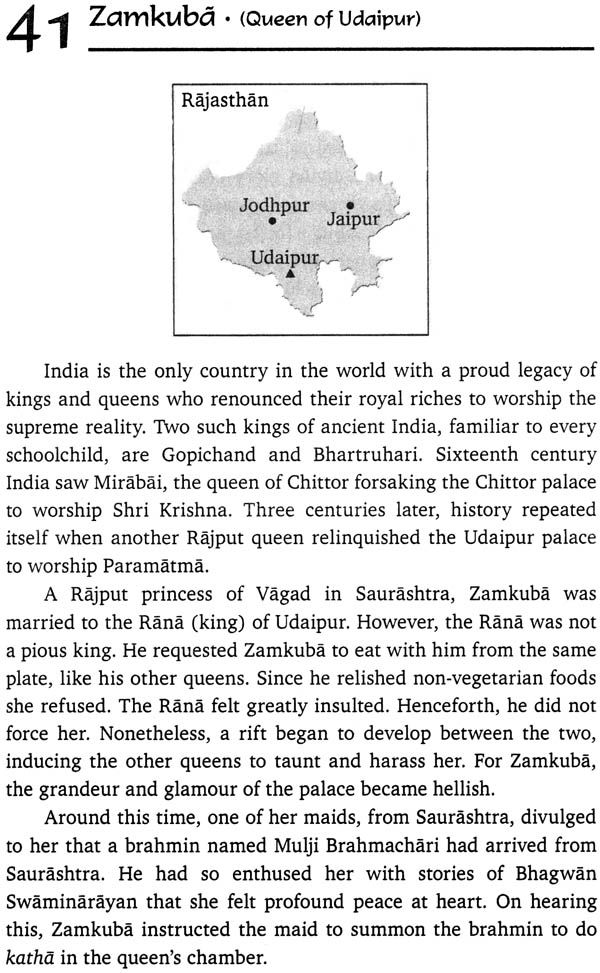

| 41 | Zamkuba (Queen of Udaipur) | 173 |

| 42 | Meenbai (Queen of Kariyana) | 178 |

| 43 | Rukmaibai | 183 |

| 44 | Rambai. | 189 |

| 45 | Kadvibai | 192 |

| 46 | Rajbai. | 194 |

| 47 | Janbai | 196 |

| 48 | Nathibai (Ganika of Jetalpur) | 198 |

| 49 | Vajiba | 200 |

| 50 | Keshaba (Queen Mother of Devaliya) | 206 |

| 51 | The Women Devotees of north Gujarat | 210 |

| 52 | Women who experienced samadhi in the 20th century | 213 |

| Afterword | 216 | |

| Appendix 1 | Vrats observed by Hindu women and girls | 220 |

| Appendix 2 | Womanhood in Sanatan Dharma’s shastras | 226 |

| Appendix 3 | List of Rishikas | 234 |

| Appendix 4 | Marriage and womanhood in the Vedas | 236 |

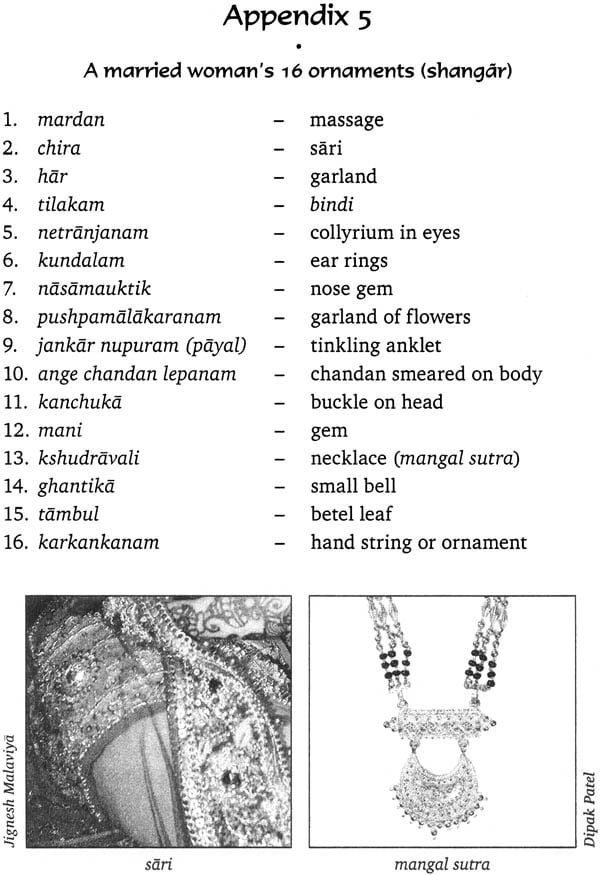

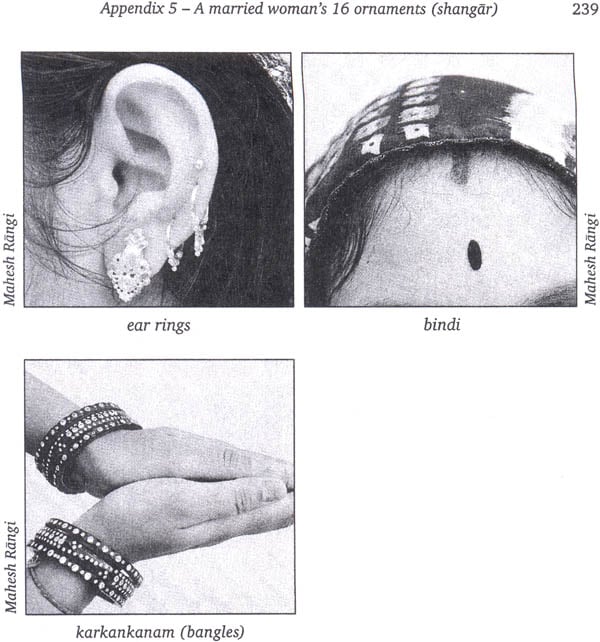

| Appendix 5 | A married woman’s 16 ornaments (shangar) | 238 |

| Appendix 6 | Attukal Pongal - The largest religious festival in the world celebrated by women | 240 |

| Appendix 7 | Daily rituals and seasonal festivals of Hindu women (photo gallery) | 242 |

| Acknowledgements | 248 | |

| Glossary | 249 | |

| Bibliography | 252 | |

| Index | 255 |