Nagarjuna's Verses on the Great Vehicle and the Heart of Dependent Origination

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDE581 |

| Author: | R.C. Jamieson |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2001 |

| ISBN: | 8124601755 |

| Pages: | 183 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.8" X 5.8" |

Book Description

R.C. Jamieson is keeper of Sanskrit Manuscripts at the University of Cambridge, a member of the Faculty of Oriental Studies, and a member of King's College. His new book, on the earliest dated illustrated Sanskrit manuscripts in the world, The Perfection of Wisdom, (New York, Penguin Viking, ISBN 0670889342/London, Frances Lincoln, 2000 ISBN 0711215103) includes all the illustrations from that historic manuscript.

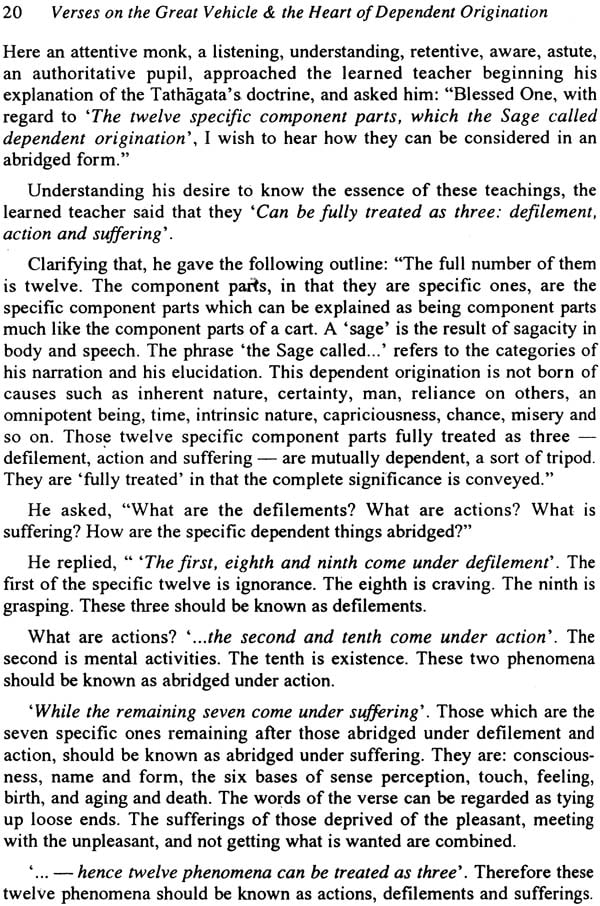

From the Jacket:No one can, perhaps, question the philosophical genius of Nagarjuna. In the dialectic of this AD second century Buddhist scholar - also acknowledged as the founder of Madhyamika school, is seen the clearest expression of Sakyamuni Buddha's profound, even the sublest teachings. Here is, in three parts, a brilliant critical study, with readable English translations, of this time-honoured philosopher's Mahayanavimsika (Verses on the Great Vehicle), Pratiyasamutpadahrdayakarika (Verses on the Heart of Department Origination) and, these besides, of his prose commentary, Pratiasamutpadahrdayavyakhyana (An Interpretation of the Heart of Dependent Origination).

Part I, comprising translation, is intended to present these Buddhist texts, is an accessible form, unencumbered by any critical material as well as other comments - for readers interested in something more than just the translation in isolation. In part 3 are incorporated, for specialists / scholars / academics, further critical comments in the light of the Dunhuang manuscripts (c. eighth-ninth centuries AD), relating to the Pratiyasamutpadahrdaya.

A remarkable combination of Jamieson's Sanskrit and Tibetan scholarship, this study is invaluable to anyone seeking a better understanding of Nagarjuna: the Buddhist philosopher and patriarch.

Preface

The purpose of the translation provided in part one is to present Buddhist texts in an accessible form unencumbered by critical apparatus. Part two provides text-critical material as well as other comment for readers interested in more than the unembellished translation in isolation. Part three provides further text-critical material and other comment in the light of the Dunhuang manuscripts which relate to the Pratityasamutpadahrdaya.

Footnotes, comment, references, bibliographic detail and so on can often obscure a text. The academic reader may become entranced by the scholarship displayed at the expense of content, while non-academic readers may simply decide that the work worthy as it might be for advancing knowledge about the literature is irrelevant and unapproachable from their point of view. The most eminent sinologist in fiction, Professor Peter Klein in Elias Canetti's Auto da Fe, presumably had a nominal readership for his exceedingly erudite work and would have been worried had it been otherwise. Of course he also receives his just deserts. His was not an ideal for which everyone would wish to strive. Be that as it may, perhaps a middle way can be found between a wooden and impenetrable but pedantically sound literalness in the approach to a text and, at the other extreme, a readable translation only very loosely based on an original source. Hopefully it will be worthwhile for those willing to make use of it. If it is not in accordance with your own notions bear in mind that it is simply what is judged to be helpful for those who have the curiosity to learn more about Buddhism's Nagarjuna.

Introduction to the Mahayanavimsika

The Mahayanavimsika is attributed to Nagarjuna in its Chinese and Tibetan versions, as well as elsewhere in Tibetan tradition. Christian Lindtner in his discussion of the authenticity of this attribution cites the Caryamelayana-pradipa, the Tattvasarasamgraha and Atisa's Bodhimargadipapanjika as ascribing the work to him, and classes the text's attribution to Nagarjuna as "perhaps authentic". This is a safe course; there is nothing to suggest attribution to another later Nagarjuna, but equally there is nothing which altogether eliminates such a possibility. Many will feel the "perhaps" is rather a strong one, as the text is often clumsy, it was not mentioned by Candrakirti, and could so easily have been compiled at a late date and then ascribed to Nagarjuna.

The Mahayanavimsika translated here is largely that of the Tibetan tradition, a version translated here is largely that of the Tibetan tradition, a version translated into Tibetan by the Kashmiri pandit Ananda and the Tibetan translator Grags 'byor shes rab.

Differences between versions of the Mahayanavimsika available to us are not limited to an occasional variant reading here and there. The number of verses, the order of the verses, and the presence of particular verses differ from version to version. The other Tibetan translation by the Indian pandit Candrakumara and the Tibetan translator Sha' kya' od has twenty-three verses. There is a Chinese translation by Shih hu (Danapala) which has twenty-four verses. There is also a text in Sanskrit the language of the original which at first sight has twenty-eight verses.

Our translation is not a wholesale reconstruction of an original text gleaned from the various versions, but some have seen it as to some extent an attempt to put into readable English the content of Nagarjuna's text as it might have been at a stage much earlier than any of the surviving manuscripts. Such a claim may not bear serious consideration and is certainly not the sort of thing that can be proven. What is offered here is a simple translation based on the rather mechanical Tibetan translation made by Ananda and Grags 'byor shes rab of their Sanskrit original, leavened with a certain amount of the very readable Tibetan translation made by Candrakumara and Sha' kya 'od of their Sanskrit original, always it he light of the one particular Sanskrit manuscript which has come down to use. The thinking behind what elements are favoured in particular instances should be clear enough in the footnotes to the edited Tibetan and in the text-critical material which follows it. The difference in approach between the two Tibetan translations is both interesting and significant. That significance is discussed after the presentation of the two Tibetan versions. Our translation consists of twenty verses, which matches rather neatly the title Mahayanavimsika, literally "The Great Vehicle in Twenty Parts", suggesting "Twenty Verses on the Great Vehicle"

The style of the verses is such that a certain attentiveness is required when reading them. the verses were composed in a way which combats the tendency to see what is expected, what is run of the mill, rather than what is actually there. The turns of phrase, the particular constructions, reflect an attempt to reward attentive reading; the ideas are mainstream Buddhism yet the style is both fresh and lively as well as authoritative. However, the style of the original is one of the things inevitably diluted if not lost in translation.

Our translation of the text setting it apart from some other versions opens with the expected verse of invocation, and then continues by saying that both, Buddhas and sentient beings, all have the same characteristics, characteristics which are much like space, not arising and not becoming extinct. In the sphere of omniscient knowledge even mental activities are void; they have arisen in interdependence upon each other, much like the two banks of a river. All existence is essentially considered to resemble a reflected image pure, tranquil in its self-nature, non-dual, and resembling its true nature. Ordinary people think there is a self in what is without self, and that enjoyment, suffering, impartiality and defilements are all real. They think that in worldly existence there are six destinies, in heaven there is ultimate enjoyment, in hell there is great suffering, and in an object there is inconceivable truth. However, unpleasantness, suffering, aging, and disease are impermanent, and the result of actions is both enjoyment and suffering. Someone deluded in worldly existence is much like a painter frightening himself with a terrifying image of a goblin, a picture which he himself has created. Sentient begins sink into the mud of false imagining, from which it is so difficult for them to extricate themselves, much as someone foolish might fall into mud he himself has made. Seeing the non-existent as existing, a feeling of suffering is experienced, and their mistaken anxieties trouble them with the poison of apprehension. Buddhas, with their minds steeped in compassion, seeing these defenceless sentient begins and acting for their benefit, urge them towards perfect enlightenment. Once their merit is accumulated, after attaining supreme knowledge, and disentangled from the net of imagining, they may become Buddhas, friends of the world. Because of seeing the true meaning, people accordingly have knowledge, and then the world is seen as void, without beginning, middle or end. They do not themselves see either worldly existence or nirvana, which is unspoiled, unchanging, originally tranquil and resplendent. Someone awakened from the sleep of delusion no longer see worldly existence, much as someone awakened no longer sees an object experienced in a dream. Those perceiving permanence, self and enjoyment, among things which are without self-nature, drift about in this ocean of existence, surrounded by the darkness of delusion and attachment. Just as they imagine the world, people themselves have not arisen. Beyond its imagined arising this has no meaning. This is all just thought, produced like a conjuring act; from it there is good and bad action, and from that there is good and bad birth. If this wheel of thought disappears, then the essence of all things disappears. There is no self in the true nature of things; that is the purity of the true nature of things. Who, without embarking on the Great Vehicle, could cross over to the other shore of the vast ocean of worldly existence full to overflowing with imagining?

| Part 1: English Translation | 1 |

| Introduction to the Mahayanavimsika | 3 |

| Twenty Verses on the Great Vehicle | 7 |

| Introduction to the Pratiyasamutpadahrdayakarika and its Pratityasamutpadahrdayavyakhyana | 11 |

| Verses on the Heart of Dependent Origination | 15 |

| An Interpretation of the Heart of Dependent Origination | 19 |

| Part 2: Critical Study and edited Tibetan texts | 25 |

| Preface | 27 |

| Theg pa chen po ni nyi shu pa | 29 |

| Theg pa chen po nyi shu pa | 39 |

| rTen cing 'brel bar 'byung ba' i snying po'i tshig le' ur byas pa | 47 |

| rTen cing 'brel par' byung ba'i snying po'i rnam par bshad pa | 53 |

| Comments | 63 |

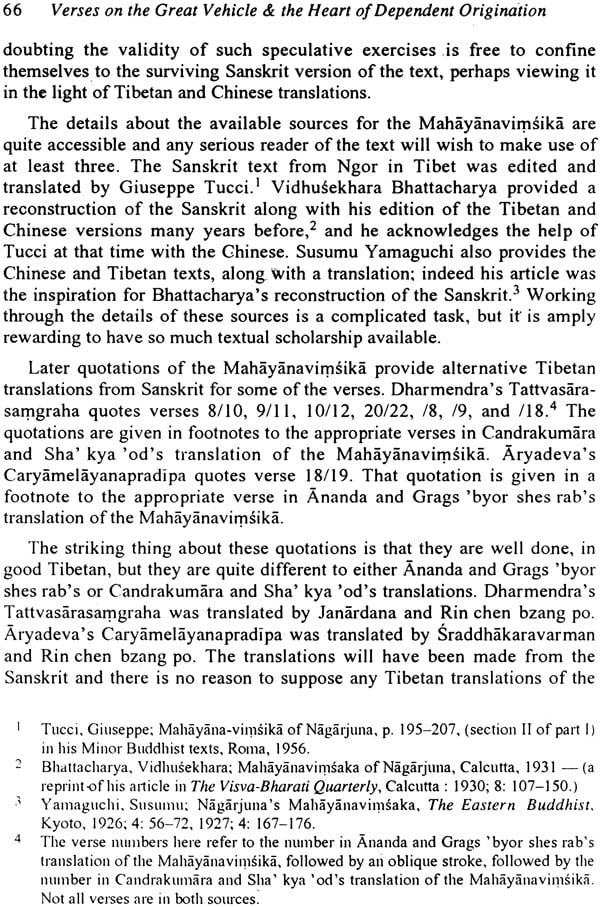

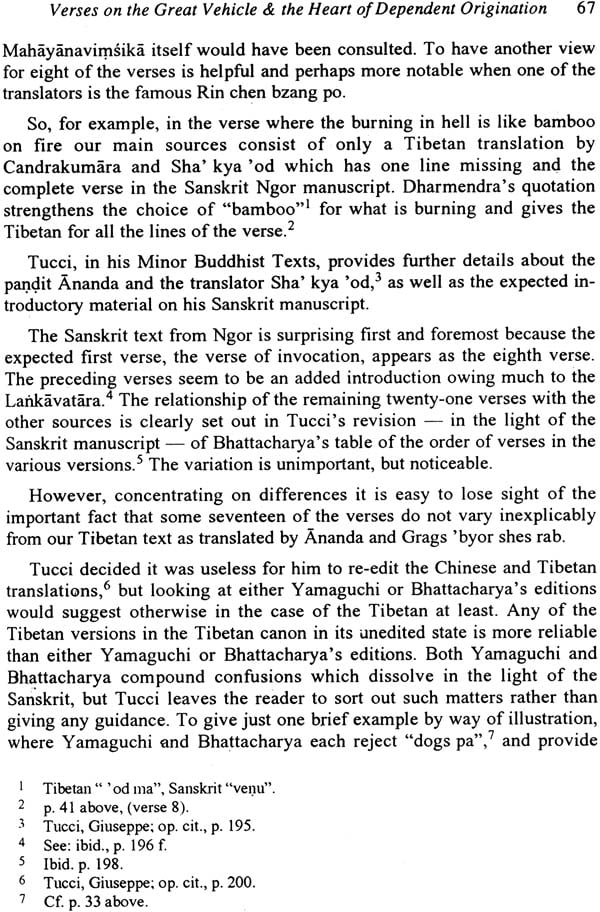

| The Mahayanavimsika | 65 |

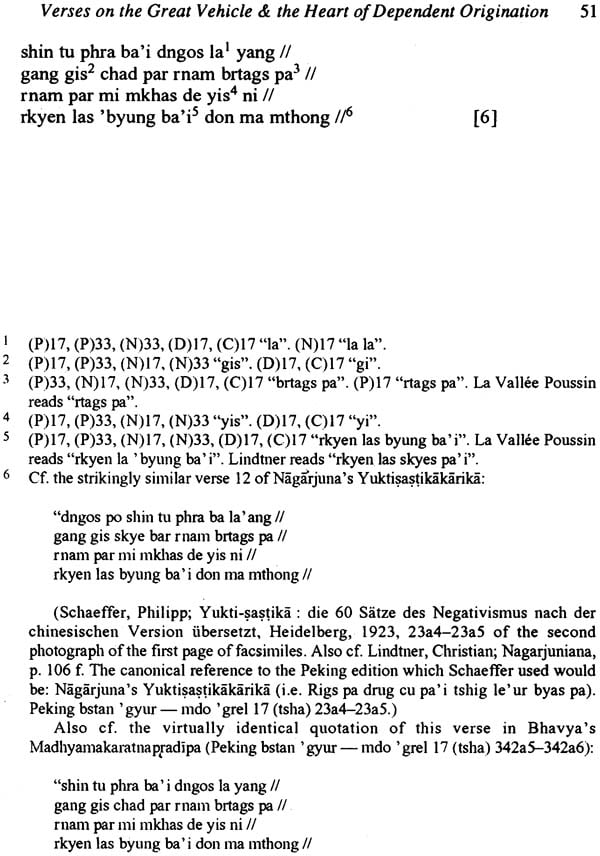

| The Pratityasamutpadahrdayakarika | 77 |

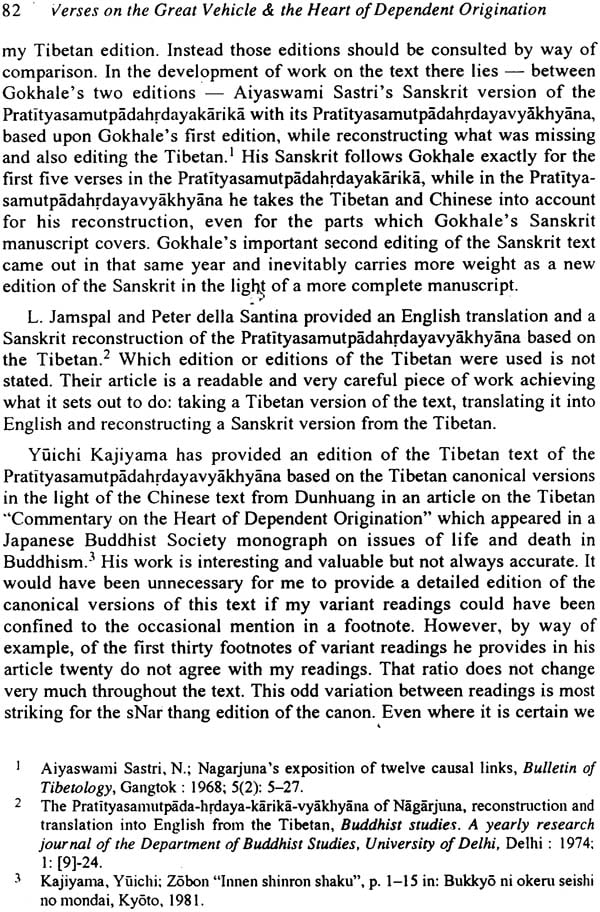

| The Pratityasamutpadahrdayavyakhyana | 81 |

| Part 3: Dunhuang texts | 85 |

| Preface | 87 |

| rTen cing 'brel pa' r 'byung ba'i snying po tshig le'ur byas pa' | 89 |

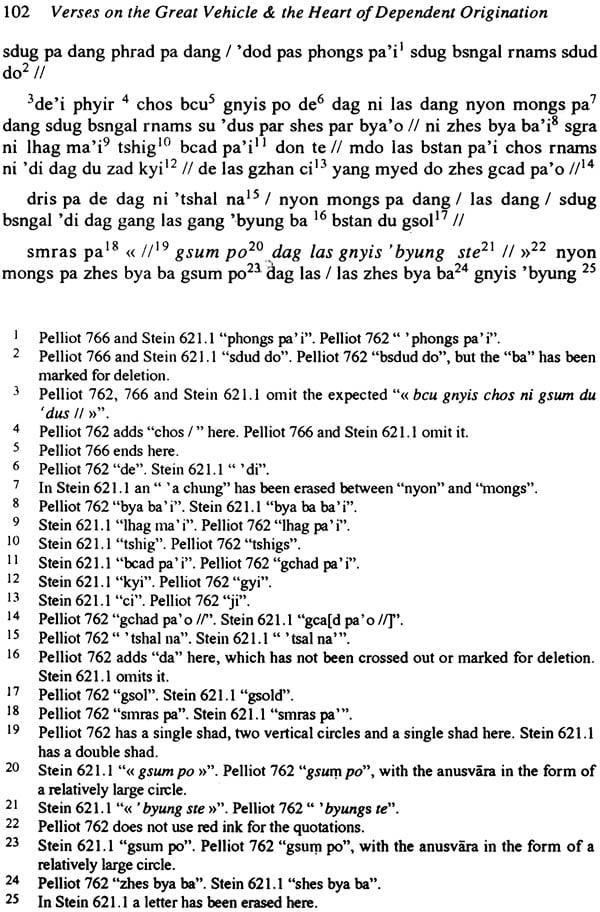

| rTen cing 'brel par 'byung ba'i snying po rnam par bshad pa | 93 |

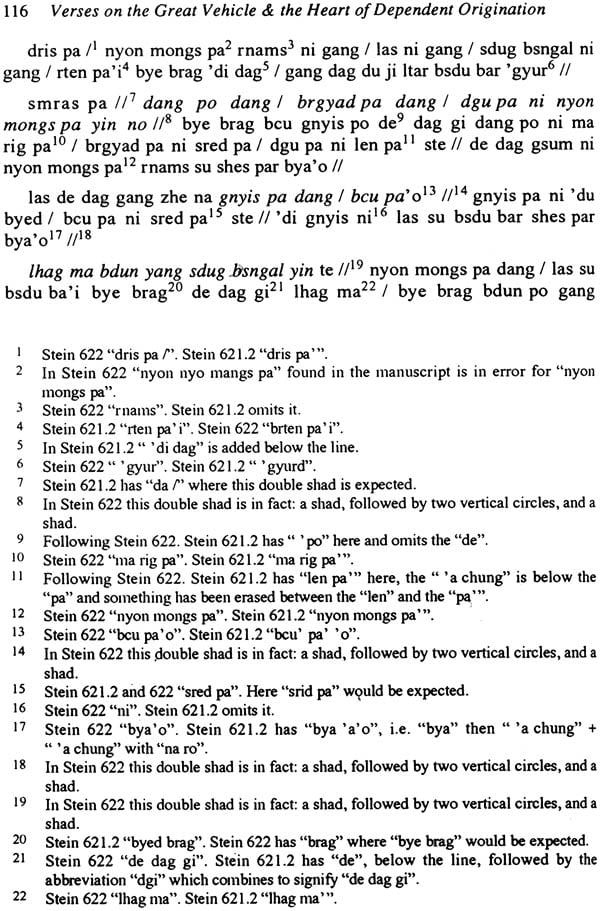

| rTen cing 'brel par 'byung ba'i snying po'i rnam par bshad pa'i brjed byang | 113 |

| Comments | 127 |

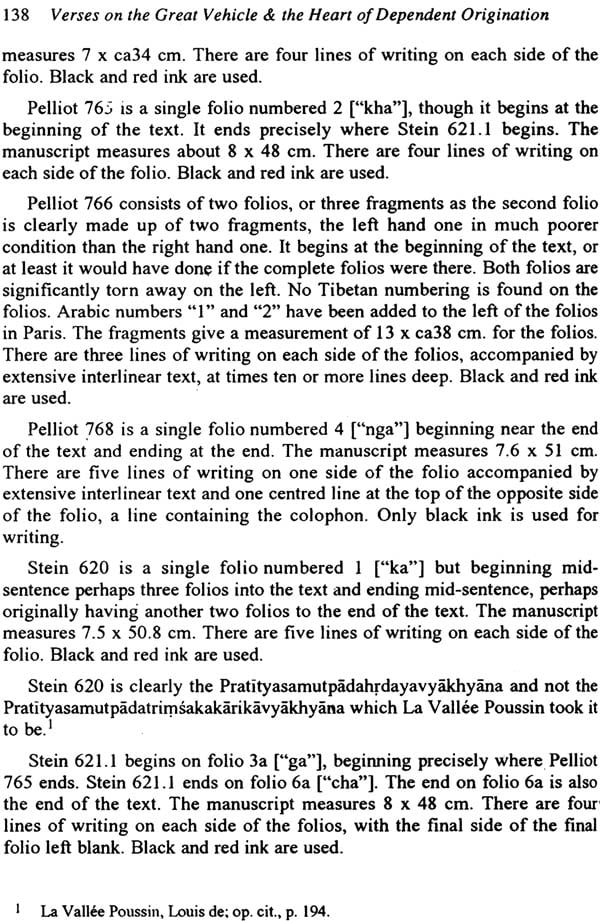

| The Pratityasamutpadahrdayakarika | 135 |

| The Pratityasamutpadahrdayavyakhyana | 137 |

| The Pratityasamutpadahrdayavakhyanabhismarana | 145 |

| Background to the Dunhuang Texts | 149 |

| Abbreviations | 157 |

| Bibliography | 159 |

| Index | 181 |

Click Here for More Books Relating to Nagarjuna