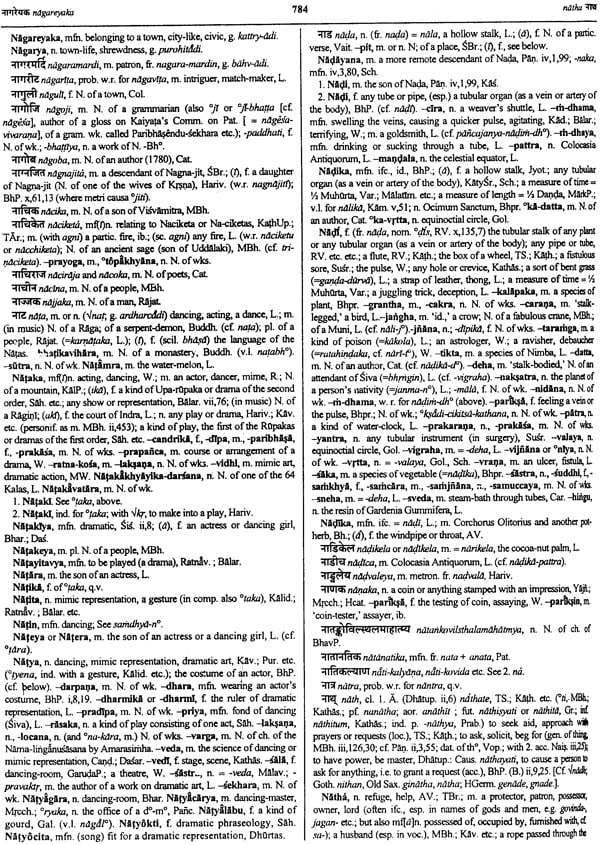

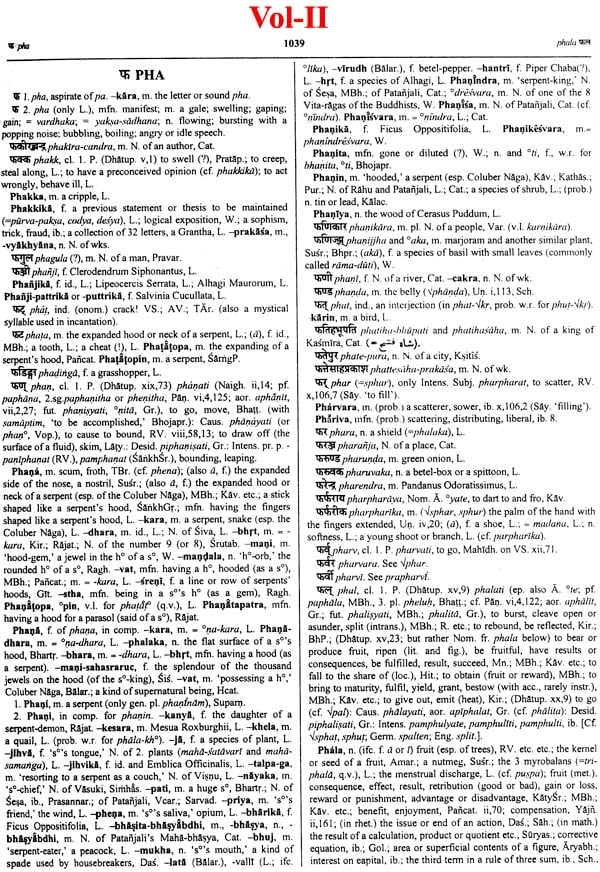

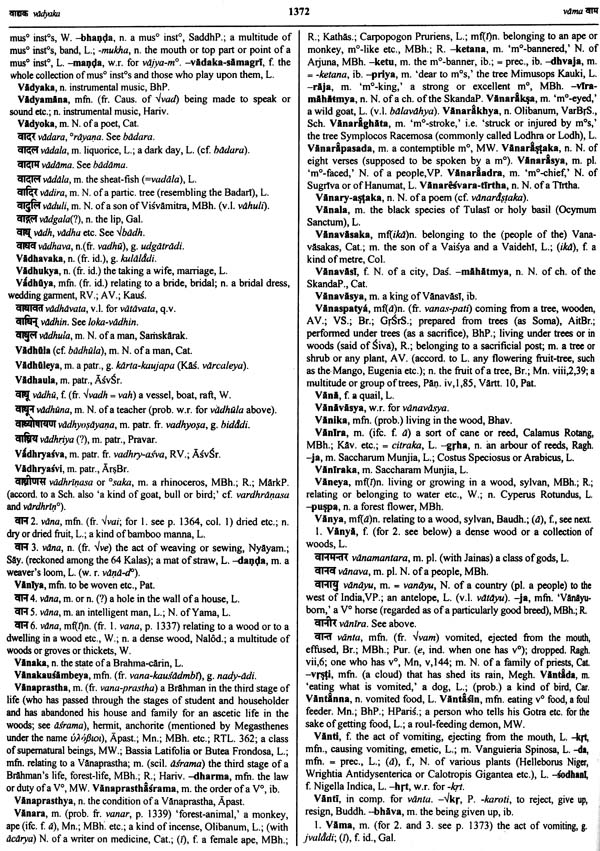

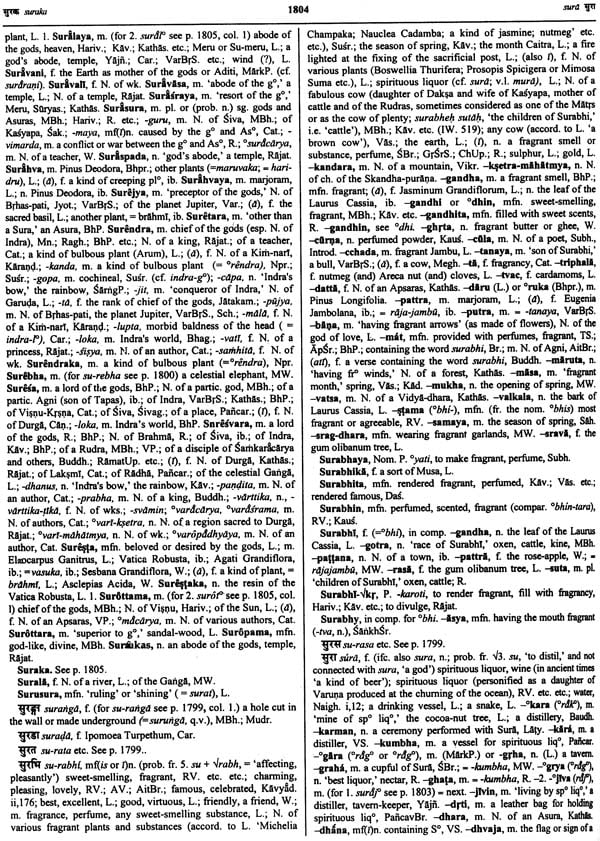

A Sanskrit English Dictionary (Set of 2 Volumes)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAR891 |

| Author: | Pandit Ishwar Chandra |

| Publisher: | Parimal Publication Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | Sanskrit Text With English Translation |

| Edition: | 2021 |

| ISBN: | 9788171103232 |

| Pages: | 1911 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 11.00 X 9.00 inch |

| Weight | 4.20 kg |

Book Description

The history of Sanskrit dictionary is, perhaps, older than that of the Sanskrit Grammar. It got started with Vedic Concordance named 'Nighantu. In reality, instead of being a dictionary, Nighantu is more or less a word. During later period, various dictionaries were compiled but, unfortunately, we have lost their original scripts. Amara Simha's 'Amarakosa has been considered to be the oldest and most popular compilation. It is also known as Namalinganusasana. In later period, Halayudha-kosa, Vaijayanti-kosa, Mankha-kosa, Nama-mala and Anekartha- samgraha etc. names are worth mentioning.

In present time, Sanskrit English Dictionary of H.H. Wilson, W. Monier and Sanskrit Worterbuch of Oto Bohtlingk's and Sanskrit English Dictionary by Vamana Sivarama Apte are the excellent works in this tradition.

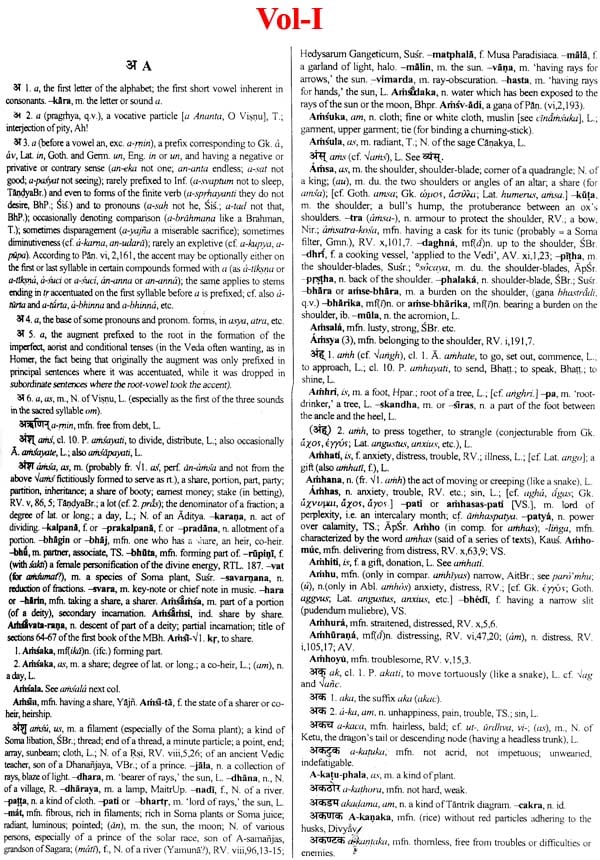

In the tradition of Dictionaries, Sanskrit English Dictionary compiled by Sir M. Monier- Williams is an important and worth praising work. It's technique of word collection is modem (as the words have been arranged in the alphabetical order, according to the first letter of the word.)

Sir M. Monier-Williams had first published his English-Sanskrit Dictionary in 1851. Subsequently, he embarked upon this Sanskrit- English Dictionary, with the primary object of exhibiting, by a lucid etymological arrangement, the structure of the Sanskrit language, the very key-stone of the science of Comparative Philology. The first edition of this Dictionary was completed in 1872. The work includes well over 1,80,000 words. The dictionary of Sir M. Monier Williams is the most popular and scholarly work of Sanskrit world, equally accepted and appreciated by Indian and Western scholars.

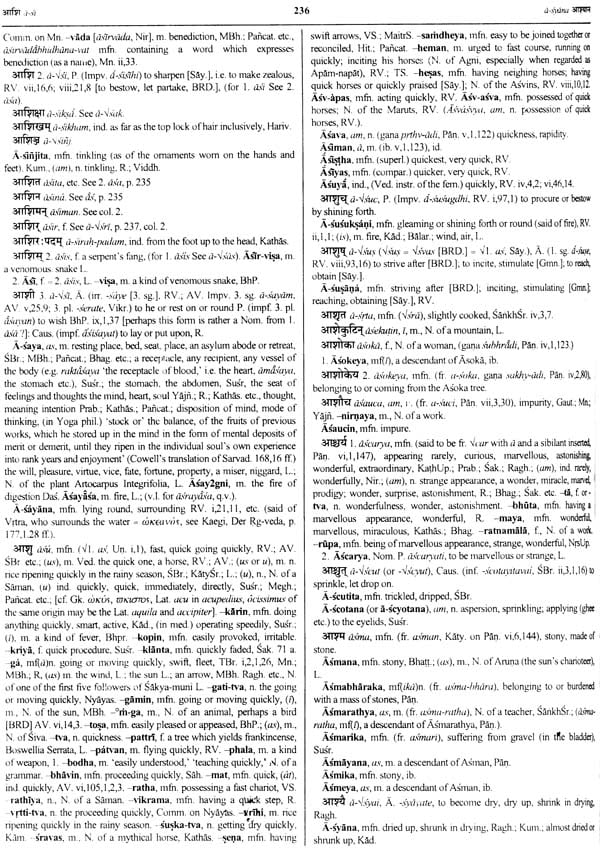

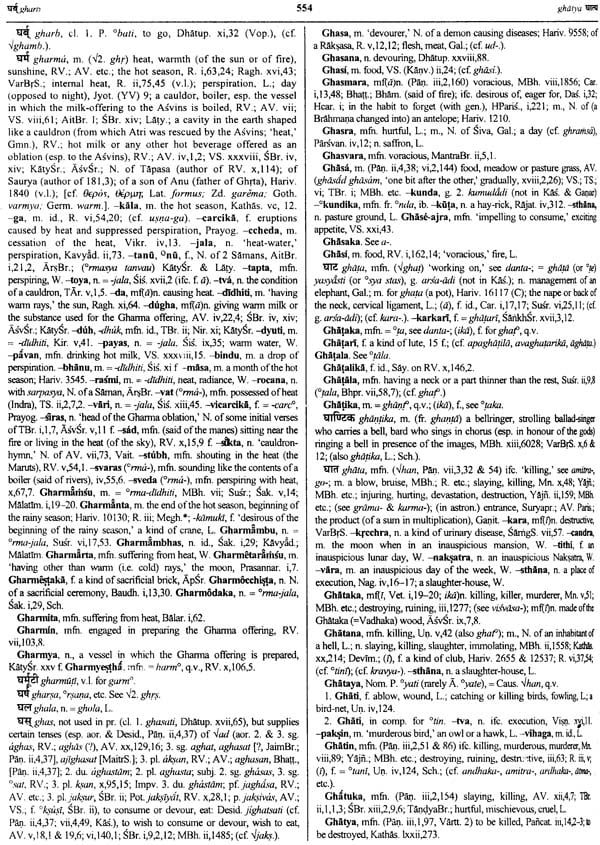

The present edition is entirely recomposed, enlarged and presented in two volumes in deluxe hard-bound format, in front of the readers. In the present edition, the earlier used diacritical notations have been replaced with their corresponding modern equivalents. The 'Additions and Corrections' portion given at the end of the original edition, has been inserted at appropriate places in the dictionary itself in the present edition.

The present edition is a result of atleast four years of hard work involved in the composing, scanning, multiple proof- readings, designing various fonts, etc. We hope this edition will fulfil the much awaited requirement of enlarged, highly- clear edition of Sir M. Monier William's Sanskrit-English dictionary.

SECTION I

Statement of the circumstances which led to the peculiar System of Sanskrit Lexicography introduced for (he first time in the Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary of 1872

To enable me to give a clear account of the gradual development of the plan of the present work, I must go back to its earliest origin and must reiterate what I stated in the Preface to the first edition, that my predecessor in the Boden Chair, Professor H.H Wilson. once intended to compile a Sanskrit Dictionary in which all the words in the language were to be scientifically arranged under about 2,000 roots, .and that he actually made some progress in carrying out that project. Such a scientific arrangement of the language would, no doubt have been appreciated to the full by the highest class of scholars. Eventually, however, he found himself debarred from its execution, and commended it to me as a fitting object for the occupation of my spare time during the tenure of my office as Professor of Sanskrit at the old East India College, Haileybury. Furthermore, he generously made over to me both the beginnings of his new Lexicon and a large: MS. volume, containing a copious selection of examples and quotations (made by P8J)~ts at Calcutta under his direction') with which he had intended to enrich his own volume. It was on this account that. as soon as I had completed the English-Sanskrit part of a Dictionary of my own (published in 1851), I readily addressed myself to the work thus committed to me, and actually carried it on for some time between the intervals of other undertakings, until the abolition of the old Haileybury College on January I, 1858

One consideration which led my predecessor to pass on to me his project of a root-arranged Lexicon was that, on being elected to the Boden Chair, he felt that the elaboration of such a work would be incompatible with the practical objects for which the Boden Professorship was founded?

Accordingly he preferred, and I think wisely preferred, to turn his attention to the expansion of the second': edition of his first Dictionary a task the prosecution of which he eventually intrusted to a well-known Sanskrit scholar, the late Professor Goldstucker. Unhappily, that eminent Orientalist was singularly unpractical in some of his ideas, and instead of expanding Wilson's Dictionary, began to convert it into a vast eyclopaedia of Sanskrit learning, including essays and controversial discussions of all kinds. He finished the printing of 480 pages of his own work, which only brought him to the word Arim-dama, when an untimely death cut short his lexicographical labours.

As to my own course, the same consideration which actuated my predecessor operated in my case, when I was elected to fill the Boden Chair in his room in 1860.

I also felt constrained to abandon the theoretically perfect ideal of a wholly root-arranged Dictionary in favour of a more practical performance, compressible within reasonable limits- and more especially as I had long become aware that the great Sanskrit-German Worterbuch of Bohtlingk and Roth was expanding into dimensions which would make it inaccessible to ordinary English students of Sanskrit.

Nevertheless I could not quite renounce an idea which my classical training at Oxford had forcibly impressed upon my mind- viz. that the primary object of a Sanskrit Dictionary should be to exhibit, by a lucid etymological arrangement, the structure of a language which, as most people know, is not only the elder sister of Greek, but the best guide to the structure of Greek, as well as of every other member of the Aryan or Indo- European family- a language, in short, which is the very key-stone of the science of comparative philology. This was in truth the chief factor in determining the plan which, as I now proceed to show, I ultimately carried into execution. And it will conduce to the making of what I have to say in this connection clearer, if I draw attention at the very threshold to the fact that the Hindus are perhaps the only nation, except the Greeks, who have investigated, independently and in a truly scientific manner, the general laws which govern the evolution of language.

The synthetical process which comes into operation in the working of those laws may be well called samskarana, 'putting together,' by which I mean that every single word in the highest type of language (called Samskrta) is first evolved out of a primary Dhatu- a Sanskrit term usually translated by 'Root: but applicable to any primordial constituent substance, whether of words or rocks, or living organisms- and then, being so evolved, goes through a process of 'putting together' by the combination of other elementary constituents.

Furthermore, the process of 'putting together' implies, of course, the possibility of a converse process of by which I mean 'undoing'. or 'decomposition;' that is/to say, the resolution of every root-evolved word into its component elements. So that in endeavoring to exhibit these processes of synthesis and analysis, we appear to be engaged, like a chemist, in combining elementary substances into solid forms, and again in resolving these forms into their constituent ingredients.

It seemed to me, therefore, that in deciding upon the system of lexicography best calculated to elucidate the' laws of root-evolution, with all the resulting processes of verbal synthesis and analysis, which constitute so marked an idiosyncrasy of the Sanskrit language, it was important to keep prominently in view the peculiar character of a Sanskrit root- a peculiarity traceable through the whole family of so-called Aryan languages connected with Sanskrit, and separating them by a sharp line of demarcation from the other great speech-family usually called Semitic.

**Contents and Sample Pages**