Tamil Language and The Timeless Translations by The Europeans (1543-1887)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAX232 |

| Author: | S. Jeyaseela Stephen |

| Publisher: | Kaveri Books |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2021 |

| ISBN: | 9789386463166 |

| Pages: | 293 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.50 X 6.50 inch |

| Weight | 650 gm |

Book Description

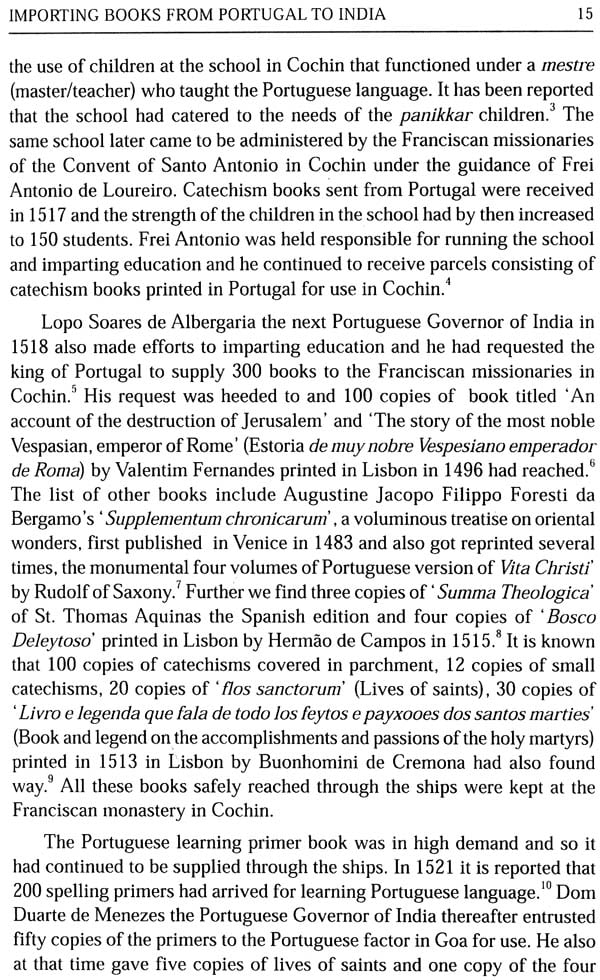

This book shows how translation served a significant step towards greater interaction and understanding between the people of Tamil country, Sri Lanka and Europe. It dwells upon a wide range of translations of the printed books from Portugal, Spain, Italy, The Netherlands, Germany, England and France to Tamil including Bible in Hebrew, Greek, German, Portuguese and Latin. It exhibits how translation became an important and integral part of the missionary work, a policy that encouraged close contacts to reach out the people. Translation from Tamil to Portuguese, Latin, German, Danish, French and English had also been executed without any impediments.

The author outlines the patterns of production, circulation and consumption of the printed works and their translations in the early modern age by giving translators their rightful place in the complex networks of authors, patrons, printers, book- sellers, and readers that shaped the market. The introduction of print media constituted an effective and a meaningful step towards Tamil prose development and translation growth.

The volume in innumerable ways very subtly explains how the missionaries came to understand Tamil language to have had links with other classical languages like Hebrew, Greek and Latin in the course of Bible translation. Tamil evolved through translations and gained fresh vocabulary and gradually built its own rules for translation. The study also reports the steps made in the translation from Sanskrit, Marathi, Bengali and Telugu into Tamil and expresses the significance.

I developed interest in finding out the literary communication that developed by the foreigners, who came to the Tamil littoral in the age of European commerce and missionary expansion. I could spot jarring omission in the existing historiography of the early modern age, on the remarkable role played by translation from Tamil to other languages and vice versa done by the translators. Hence I commenced my work with special reference to the region of Tamil country, but gradually felt the importance to include the French territory Pondicherry, and also the island of Sri Lanka, chiefly because the Tamil translations occurred had embedded together. The translation works in these territories had involved different styles, scales and needs directed by fundamental divergence in prose. However, Tamil language had stood as the bridging element and culture being the common denominator. Thus the book provides new information on the interesting interconnections and the pivotal role played in communication history and translation studies.

This volume is made possible by an enormous amount of help from many people. I owe a substantial debt to the Fundacao Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisboa, for the invaluable help of research grant extended to me in assisting to conduct research in the various archives and libraries in Europe for two years, Instituto de Cultural e Lingua Portuguesa, Ministry of Education, Government of Portugal for awarding a fellowship for one year to do research in the repositories in Portugal. Therefore, I extend my sincere and warm thanks. Many institutions and people shared with me data, information and documents and in this connection I wish to express my gratitude to repositories and authorities of Academia das Sciencias, Lisboa: Arquivo Historico Ultramarino, Lisboa: Biblioteca da Adjuda, Lisboa; Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa: Biblioteca da Cartuxa, Evora; Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Citra del Vaticano; Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu, Roma; Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris; Archives de la Societe des missions etrangeres de Paris; Bibliotheque Asiatique des missions etrangeres de Paris; Bibliotheque Municipale de Chalon-sur-Saone: Hendrik Kramer Instituut, Oegstgeest; Universitats Bibliotheek Gottingen; Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Kobenhavn; Universiteits Bibliotheek, Leiden; Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag; Universiteits Bibliotheek, Utrecht; Universiteits Bibliotheek, Amsterdam; Archiv der Franckeschen Stiftungen, Halle; Bibliothek der Franckesche Stiftungen, Halle; Staats-und Universitatsbibliotheek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzy; British and Foreign Bible Society's Library, Cambridge; British Library, London; Bodleian Library, Oxford; British International Bible Society, London; Houghton Library of Harvard University, New York Public Library and the American Bible Society Library, New York for the numerous help and extending great assistance. Further, I also thank the authorities of the Sri Lanka National Archives, Colombo; Archives of the Gurukul Lutheran Theological College and Research Institute, Chennai; Tamilnadu State Archives, Chennai; State Central Library, Goa; Madurai Province Jesuit Archives, Shenbaganur; Archives of the United Theological College, Bengaluru; National Archives of India, Pondicherry and Saraswathi Mahal Library, Thanjavur for permission to consult and use the resources available. Finally my thanks go as well to Shri Abhishek Goel, Kaveri Books for printing the book.

Evolution of Translation and Translating in Tamil before Print India the country in the ancient past had people of many dialect and Language speaking groups. In the southern part of the country Tamil was widely spoken on the coast and hinterland. The Romans and the Greeks had established maritime contacts with Tamil coast and these foreign language speaking groups have been mentioned in the Aganaanuru and Pettinepeelei The Arabs and the Chinese in the medieval period had also established commercial contacts with Tamil coast.

They communicated with each other and had exchanges. However, we have no concrete evidences of development of translation of foreign literary texts to Tamil and vice versa. The study of the history of translation in India had been though undertaken by scholars tile subject of the Tamil language translation had been largely ignored. Tamils came into contacts with people who spoke Pali and Prakrit in the northern India. It happened chiefly because of the rise of the religious contacts of jainism and Buddhism. The available earliest reference to translation is found in Manimegalai an epic in Tamil which contains fourteen lines of text translated from a pidagam in Pali language. Myilai Seeni Venkatasamy opines that this translation was done from word for word.' Kundalakesi another epic in Tamil contains translation from Therikaathai in Pali language." Thus contacts of Pali language with Tamil and translation of Buddhist texts had happened at first than any other language of India. It should be mentioned that the early inscriptions of the Pallava rulers at Manchikallu, Mayadivolu and Hirahadagalli were in Prakrit. Thus Prakrit language also had been popular and it had happened much before introduction of Sanskrit. The royal charters issued by the Pallava rulers in Sanskrit were much later in date.

What is the history of translation? In the modern sense March Bloch the historian says that the translation of history is the study of the act of translation in time, which is made up of three levels: the translation agent, the translated works, and the act of translating analyzed and shown diachronically.' However it is important to know what was called translating and translation in the ancient past and how it had been handed over down the ages.

Tholkappiyam the Tamil grammar refers to translation with the use of the term . Athaarpada Yaathal'. It literally refers the shadow copy made from the original in another language. Tholkaapiyar mentions neatly the two types of texts i.e., from source language and the target language." Further, the translated texts have been referred to be of four kinds such as thogai nooI (summarization), viri nooI (elaboration), Thogei-viri nooI (synthesis of summarization) and mozhipeyarpu nooI (translation).

Regarding the translation policy to be adopted Tholkappiyar had said that while translating into Tamil those special letters and words of the northern languages should be omitted. He categorically stated that only those suited to Tamil language should be used." We find Sanskrit words like pangkajam and nashtam have been expressed in Tamil as pangkayam and nattam. In the ManimegaIai epic we find Lakshmi the term had been expressed as Lakkumi in Tamil. Hence it is known that translation was very carefully done in Tamil with from word to word.

Sanskrit interaction with Tamil developed during the time of the Pallava ruler Simhavishnu and Nandivaraman II in AD. 730. Sanskrit language came to be patronized by the Pallava rulers and in Tamil country they began to issue royal orders in bilingual. The first portion of the inscription was written in Sanskrit verses as well as in prose and the latter half was written in Tamil. The Pandya rulers and the Cholas also followed the same style and we find numerous bilingual inscriptions in Sanskrit and Tamil. It was at that time Kalidasa the Sanskrit poet came to be introduced to Tamils as we find mention in inscriptions. The Raguvamsam of Kalidasa is also mentioned in the Kuram plate of Pallava Parameswaran and also in the Velvikudi grant of the Pandya ruler. The composers of the Sanskrit portion of the inscriptions being students of Sanskrit literature they freely borrowed portions and introduced it. We find even some verses from the Agni Purana mentioned in an epigraph praising Udvahanatha at the temple of Tirumananjeri near Mayiladuthurai area.

Ramayanam (the story of Rama) in Sanskrit had been well known to Tamils as mentioned in the sangam literature of Puranaanuru. Silapathikaaram the first epic in Tamil also mentions Ramayanam." Kalithogai also refers to it. However Ramayanam the epic in Tamil came to be composed by Kambar only in the twelfth century. IS Sheldon Pollock opines that adaptations from Sanskrit appeared in Tamil opposed to Sanskrit. Hence his view may be called into question for there was no rivalry or monopoly of languages.

Mattavilasaprahasana the farcical play in Sanskrit was composed by Mahendra Varman I the Pallava ruler. The Bhagavadajjukkam another play has also been assigned to him. Stories found in Sanskrit had lured the Tamil poets. The story of Sivakan is found in the uttarapaaham of Mahapuranam in Sanskrit. The same story appears in Sathya Chintamani and Shathira Chudaamani in Sanskrit. Thiruthakka Devar adapted this story of Sivakan and he composed an epic in Tamil titled Sivaka Chintemeni in the ninth century. IS The story of Nazhlan found in one of the branch tales of Mahabharatham was composed by poet Pughalyendi titled Nazhla Venpa (the story of Nazhla in venpa metre) in the thirteenth century. Perhaps these stories were not popularly known and imperfectly understood by the people of that period and that had necessitated for adapting into Tamil.

**Contents and Sample Pages**