Thirupporur and Vadakkuppattu - Eighteenth Century Locality Accounts

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAK246 |

| Author: | M. D. Srinivas, T. G. Paramasivam and T. Pushkala |

| Publisher: | Center for Policy Studies, Chennai |

| Language: | Tamil and English |

| Edition: | 2001 |

| ISBN: | 8186041141 |

| Pages: | 218 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 340 gm |

Book Description

The Chengalpattu Survey of 1767-1774 was perhaps the first effort that the British made to understand the ways of the Indian people before devising modes of effectively subjugating and administering them. Accounts of over 2100 localities of the Chengalpattu region of Tamil Nadu were collected as a part of this Survey. These accounts present the most detailed picture available anywhere of the functioning of Indian society, economy and polity at its basic level, before it was disrupted and transformed through the instruments of British administration.

We have so far been led to believe, on the basis of rather tenuous historical evidence, that India of that time was a poor, scientifically and technologically backward, and socially and politically dysfunctional nation. The locality accounts of the Chengalpattu Survey present a picture of Indian society and polity that is the exact opposite of these images of poverty and dysfunctionality.

This book presents detailed accounts for two localities, Thirupporur and Vadakkuppanu, in the original Tamil script of the palm-leaves and in English translation. The introduction gives an overview of the Chengalpattu information and highlights some of the important features of the society, economy and polity of Thirupporur and Vadakkuppanu.

Tamil University of Thanjavur holds some 160 bundles of palmleaf records, which were transferred there about 15 years ago from the office of the then Collector of Chengalpattu District at Kanchipuram, where they had been lying for perhaps the last two hundred years. Each of these bundles contains on the average about 600 uncut and untreated palm-leaves, each about a metre long and 3-4 centimetres wide, with writing on both sides in old Tamil script. These manuscripts preserve the 18th and early 19th century locality accounts of the Chengalpattu region of Tamil Nadu, which forms a part of the cultural area traditionally known as Thondaimandalam. The accounts present the most detailed picture available anywhere of the functioning of Indian society, economy and polity at its basic level, before it was disrupted and transformed through the instruments of British administration.

Of the 160 bundles of palm-leaves, about 20 contain accounts collected between 1767 to 1774 at the instance of a British engineer, Thomas Barnard, and Rajasri Chengalvaraya Mudaliar, who served as an interpreter, dubash, for the British. These accounts, referring to about 1,500 localities, are part of the original data that formed the basis for an extensive survey of about 2,100 localities of Chengalpattu, undertaken by Mr. Barnard on instructions from his superiors in the British administration. From these palm-leaf records he got some information extracted and translated to a specific format. About fifty volumes of these English Summary records are available in the Tamil Nadu State Archives at Chennai.

The Chengalpattu Survey of 1767-1774 was one of the first efforts that the British made to understand the ways of the Indian people, before devising modes of effectively subjugating and administering them. The information recorded in the survey is extraordinarily important. It obliges us to revise our ideas about life and Society in India towards the latter half of 18th century, just prior to the establishment of British administration. We have so far been led to believe, on the basis of rather tenuous historical evidence, that India of that time was a poor, scientifically and technologically backward, and socially and politically dysfunctional nation. The accounts presented in these manuscripts, however, present a picture of Indian society and polity that is the exact opposite of these images of poverty and dysfunctionality.

Our attention was drawn to these palm-leaf manuscripts through the work some of us at the Centre for Policy Studies had begun more than ten years ago on the archival records of the survey. The English archival records have now been copied and compiled into a database at the Centre for Policy Studies. The palm-leaf records, wherever available, add graphic details to the archival records and present a vivid picture of the locality in all its varied aspects.

The palm-leaf manuscript accounts for several hundred localities have also been copied in a collaborative exercise between the Centre for Policy Studies, Chennai and the Department of Palm-leaf Manuscripts, Tamil University, Thanjavur. Pulavar V. Chokkalinga Swamigal and Pulavar B. Kannayyan helped with the copying and transcription of these manuscripts at the earlier stages; later much of the copying was done by one of the authors, T. Push kala. The last named author also presented an analysis of the Tamil palmleaf accounts for about ten localities in her thesis, Chengalpattu Avanangal: Samudaya Poruladharam, which was awarded the Ph.D. degree by the Tamil University, Thanjavur, in 1998.

In this book we present detailed accounts for two localities, Thirupporur and Vadakkuppattu. These are first presented in the original script of the palm-leaf manuscripts, for which special fonts have been developed. This is followed by an English translation of these locality accounts. For the sake of comparison, we have also reproduced the English summary accounts for these localities from the English archival records. The book also includes an introduction giving an overview of the Chengalpattu information and highlighting some of the important features revealed in the detailed accounts of Thirupporur and Vadakkuppattu.

It is our pleasant duty to express our deep sense of gratitude for the invaluable advice, encouragement and help we have received from colleagues and associates at the Centre for Policy Studies: Sri Dharampalji, Dr J. K Bajaj, Sri T. M. Mukundan, Prof. Ashok Jhunjhunwala, Prof. G. S. R. Krishnan, Sri KN. Govindacharya, Sri S. Gurumurthy, Dr. Sekhar Raghavan, Prof. K V. Varadarajan and Smt. Vijayalakshmi Srinivas; and those at the Tamil University, Thanjavur: Prof. M. N. Shanmugam Pillai, Prof. Y. Subbarayalu, Pulavar P. V. Nagarajan, Dr. V. R. Madhavan, Thiru C. Lakshmanan, Thiru M. K Kovai Mani and Mrs. T. Kala. We have also benefited greatly from the kind appreciation received from Prof. Tsukasa Mizushima of Tokyo University who has himself done extensive work on the Chengalpattu Survey of 1767-74.

We are grateful to Dr. Kadir Mahadevan, the Vice Chancellor of Tamil University, for encouraging this work and for kindly agreeing to contribute a Foreword to the book. We would like to record our gratitude to the earlier vice-chancellors of Tamil University, especially Prof. V. 1. Subramanion, who contributed to make this collaborative work possible and fruitful.

We are grateful to Sri Muralikrishna of Anu Graphics for developing the special Tamil fonts, and thus enabling us to reproduce the Tamil accounts in the manner they are written in the eighteenth century palm-leaf anuscripts. We are also grateful to Sri Srinivasa Rao of Spectrum Graphics for typesetting this part of the book. We are grateful to Sri Bal Menon of Laser Words for his enthusiastic support in all our endeavours and for typesetting the English part of the book.

We respectfully record our obeisance and gratitude to Kanchi Kamakoti Pithadhipati Jagadguru Sankaracharya Sri Jayendra Saraswati Swamigal and Sri-la-Sri Thondaimandala Adheenam for being kind enough to go through this work and send their blessings.

This book on Thirupporur and Vadakkuppattu: Eighteenth Century Locality Accounts, is based on the eighteenth century palm-leaf records of the Chengalpattu District. Chengalpattu District is part of the culturally rich Thondaimandalam region, which is renowned as the home of men of great wisdom. This region is also important for historical studies, as it was the first to come under British rule in South India.

While the stone and copper inscriptions give us only glimpses of the history till the modern period, these palm-leaf locality accounts of eighteenth century are an invaluable source of the history of recent times. They record, in a systematic manner, a great deal of information about most of the localities of Chengalpattu District. They present the most detailed picture available anywhere of the nature and functioning of Indian society, economy and polity at its basic level prior to the establishment of British rule and in fact lead us to an entirely new perspective on the traditional Indian society and polity.

It is our good fortune that such extensive records, which do not seem to be available for any other region of India, are available with us. This book presents, for the first time, detailed locality accounts of two localities in both Tamil and English. It is indeed a signal contribution to historical studies.

This admirable effort has been jointly undertaken by the Centre for Policy Studies, Chennai and the Department of Palm-leaf Manuscripts of the Tamil University, Thanjavur. The dedicated and incisive work of the scholars of these institutions, Prof. T. G. Paramasivam, Prof. M. D. Srinivas and Dr. T. Push kala deserves all appreciation.

A notable feature of this book is the fact that the eighteenth century locality accounts are presented in the original script of the palm-leaf manuscripts, for which special fonts have been developed. There is a general impression that most investigators hesitate to take up manuscripts and other original records for study because of the difficulties involved in deciphering the special characters and symbols that occur in these records. In this context, the editorial note in the Tamil version of this book would be a valuable introduction to the researchers who wish to embark on such a study.

This book will be of great significance to scholars both in the: fields of History and Manuscriptology. We wish the authors all success in their endeavour to edit and publish the locality accounts of several more localities for the benefit of the scholarly world.

THE CHENGALPATIU SURVEY: 1767-1774 The English Archival Records Chengalpattu District stretches in a wide arc, about 180 km long and at places up to 80 km wide, around the city of Madras, capital of Tamil Nadu and the seat of British colonial power in South India. The areas falling in this District were presented to the British in October 1763 by Mohammed Ali, the then Nawab of Arcot; subsequently the British referred to these areas as the Jaghire. The Jaghire lands, surrounding Fort St. George from three sides, were of obvious strategic importance to the British. To determine the value of these lands, and also to arrive at appropriate ways of governing the Jaghire, the British undertook a detailed survey of more than 2,100 localities comprising it. The survey was conducted by a British engineer, Thomas Barnard (1746-1830). Mr. Barnard started work in February 1767, and took more than seven years to complete the survey in November 1774.

The records of the survey, giving details of the inhabitants, their habitation, land use pattern, cultivation, trade, production and distribution etc., for the 2,100 localities of the region were submitted to the Madras Board of Revenue, and were taken on record during 1775-76. The records are available in the Tamil Nadu State Archives, Madras in the form of longhand registers. There are thirty-nine volumes in the Board of Revenue Miscellaneous Series! and ten volumes in the Chengalpattu District Record Series", containing the survey data. Most of these volumes are in a dilapidated condition. Scholars at the Centre for Policy Studies have collected the complete archival data of this survey from the archival registers and compiled it into a database.

Survey Districts and the Region

The region referred to as Jaghire by the British consisted of 15 Simais: Kovalam, Chengalpattu, Kavanthandalam, Kanchipuram, Manimangalam, Uttiramerur, Periapalayam, Poonamalee, Ponneri, Salappakam, Sattumaganam, Thiruppatchur, Karunguzhi, Perambakkam and Sriharikota. The survey volumes are divided according to the Simais; each Simai constitutes a separate survey district.

The 15 Simais constituting the survey region were further divided into about 250 Maganams. These divisions of the eighteenth century Chengalpattu are probably related to the traditional division of Thondaimandalam into Kottrams and Nadus. The Taluk of today seems coterminous with the Simai.

Data from a total of 2,138 localities belonging to the 15 survey districts are recorded in these registers. Records of about 40 localities in the Thiruppatchur Simai do not find a place in the available registers. Localities of the so-called Home Farms of Mylapore and Thiruvottiyur also are not covered. Almost all of the 2,138 localities covered in the survey, 2,200 if we count some of the hamlets as independent habitations, fall in the Kanchipuram and Thiruvallur Districts of today (or what used to be the Chengalpattu District till recently); about 20 form part of the Vellore and Thiruvannamalai Districts (parts of the earlier North and South Arcot Districts). The survey covers almost the whole of the Kanchipuram and Thiruvallur Districts, excepting the Taluks of Thiruttani and Pallippattu.

Tamil Palm-Leaf Manuscripts

The English records of the survey were prepared from more detailed Tamil palm-leaf accounts, which it seems, were kept in every locality. Referring to such accounts Mr. Barnard, in his letter of 10th November 1774 addressed to the Governor-in-Council at Fort St. George, noted:"

To accomplish what was required of me, in reporting the state of the country, and the improvements which might be made, I had recourse to the records which are kept in every locality of the transactions, which relate to revenue, cultivation and trade. The existence of any such materials was I believe unknown, when Col. Call sent me out, the insight I obtained of this matter, was furnished me by the interpreter appointed by Col. Call. ... The extract I caused to be made from the records, contain the quantity of disposal, and appropriation of the grounds in every locality, the number of the inhabitants with their possessions, and privileges, where they are entitled to any, also the total of cattle in every locality. The revenue account consists of the neat produce of each locality adjusted according to a standard fixed at the time of Doast Ally6 for ascertaining the rights of the cultivators. This produce is shown for five succeeding years from 1761. In some places I have obtained a similar account of the administration of Doast and Subder Ally.' But it has not happened often ...

The extracts from the original locality accounts in Tamil, which Mr. Barnard refers to above and which were first prepared in Tamil in the form of palm-leaf manuscripts, are occasionally referred to in the government records of eighteenth century. These palm-leaf manuscripts, probably written in a format similar to the traditional locality accounts, were deposited with the Collector of Chengalpattu around 1795. A few years ago, the Department of Palm-Leaf Manuscripts of the Tamil University at Thanjavur acquired these and several other eighteenth and nineteenth century palm-leaf records of Chengalpattu localities.

The material obtained by the Tamil University from the office of the then Collector of Chengalpattu at Kanchipuram consists of about 160 bundles of palm-leaf manuscripts. Of these about 20 bundles contain material related to the Chengalpattu Survey of 1767 -1774. The other bundles are of a later period.

Each of these bundles contains on the average about six hundred uncut and untreated palm-leaves, each about a metre long and 3-4 centimetres wide. The leaves are written on both sides. The 20 bundles of the Chengalpattu Survey material thus run into about 12,000 leaves, with 24,000 sides of writing. The data in these leaves refers to about 1,500 localities; the information is fairly complete for about one thousand.

Script and the Symbols

The manuscripts are written in the older Tamil script usually employed by traditional Tamil Account-keepers, the Kanakkappillais, and use several special symbols, especially for fractions, numbers, units and measures, etc. The standard eighteenth century script is fairly well known among Tamil manuscriptologists. We have deciphered some of the special symbols by comparing the Tamil accounts of individual localities with the corresponding archival records in English. The details of our interpretation of the script and the symbols are given in an editorial note in the Tamil version of this book.

Sections and Dunsions

The accounts are divided into several divisions or sections. Leaves in each section or division have a distinct name, and are gathered together in separate bundles. Thus several bundles contain leaves described as the Tarappadi Vagai Edu that give details of the land and households in the locality, and sometimes also of grain production and revenue. There are other bundles containing leaves entitled the Sutantira Tittam and Merai Chattam that give details of the sharing of the produce between different beneficiaries. Yet other bundles contain En Alavu leaves, giving details of the expenses of and expected incomes from the repair of irrigation tanks, the Eris; and so on. Leaves in two of the bundles are termed Tirvai Vagai Edu; these give details of the calculation of revenue from the gross produce. There are also some bundles with leaves named Beriz Tugai Edu that record only the assessed revenue. Several of the Tarappadi Vagai Edu bundles also contain a summary of the data, which is referred to as the Tugai Edu of the locality. It is probably these summary data sheets that were translated into English and recorded in the archival survey registers.

The Tarappadi Vagai Edu leaves give a detailed account of the land and households in a locality. They identify every piece of land in the locality, locating it with respect to the centre of the locality, and recording the use to which it is or may be put. Every temple, pond and grove, referred to by the terms Kovil, Kuttai, Kulam, Tangal, Toppu, Tottam, ete., is identified and its extent recorded. And, every household in the habitation is identified with the name and community of the head of the household; and its location within the habitation, its size and the extent of the attached backyard are mentioned.

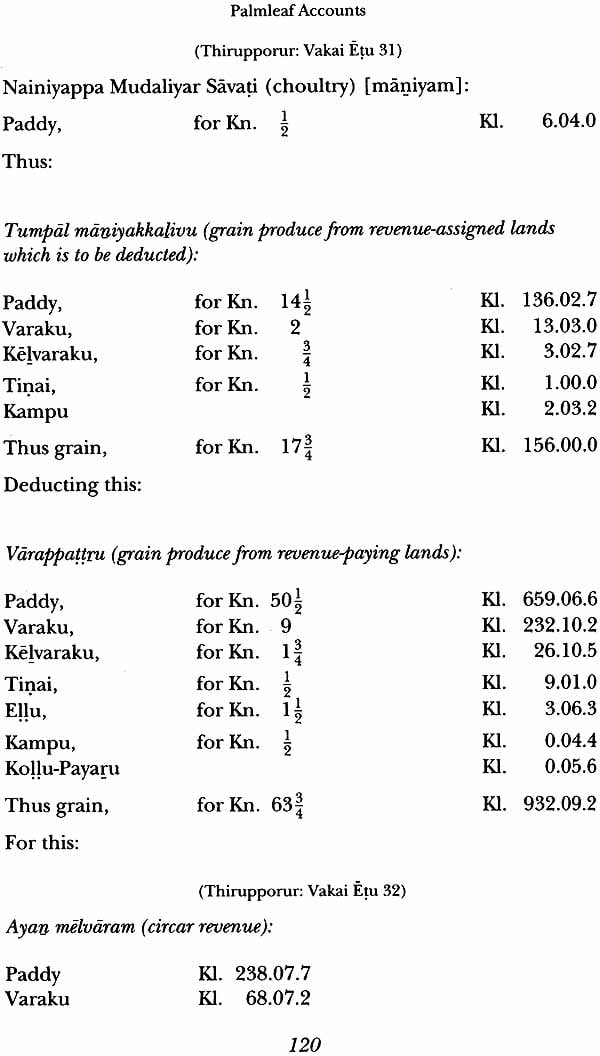

The Tarappadi Vagai Edu also record the extent of cultivated lands in a locality, and give details of the amount of cultivated land held as Maniyam, revenue-free assignment, and the names of the beneficiaries of these Maniyams. Often the Tarappadi Vagai Edu also record the actual extent of cultivation under each crop and the produce for the years 1762 to 1766.

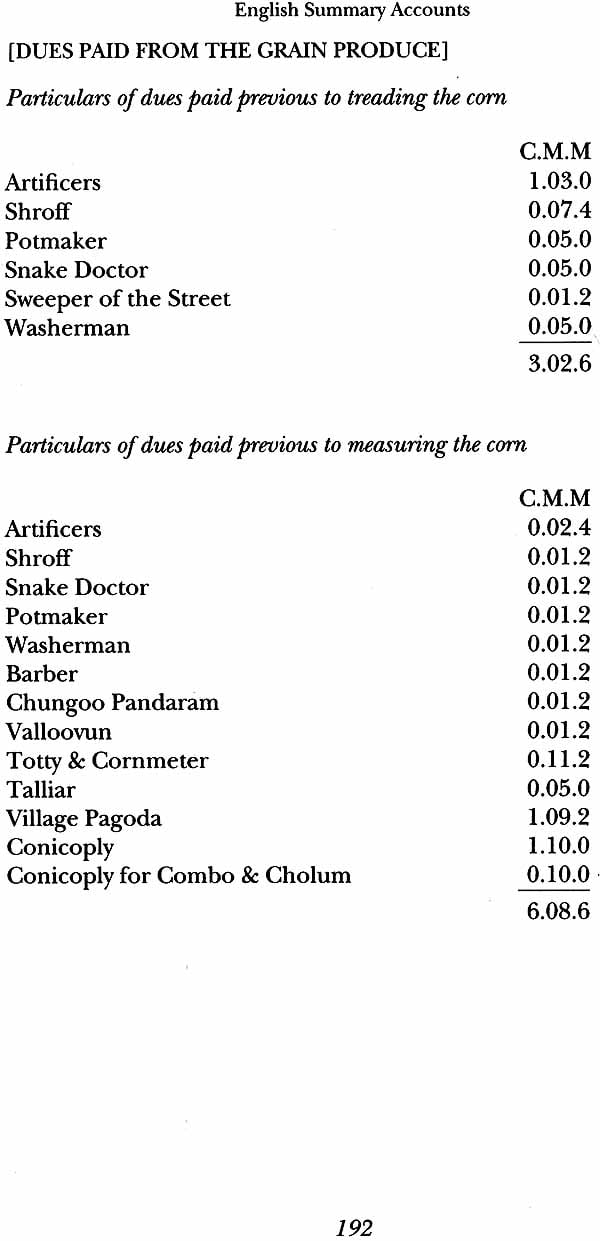

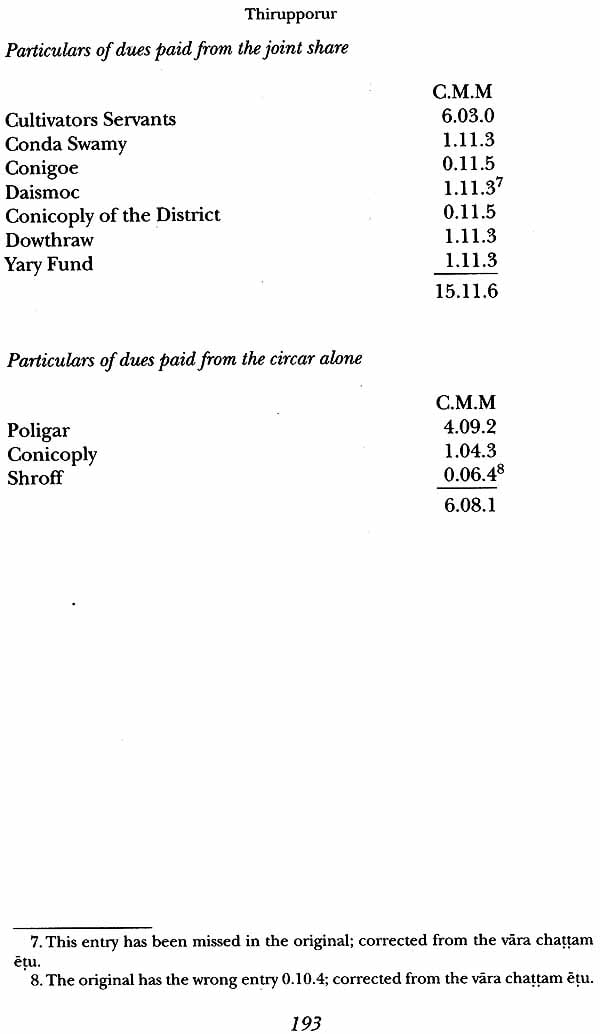

The Sutantira Tittam and Merai Chattam leaves give a detailed description of the deductions made from the produce for different functions and institutions of the locality and the region. Shares are taken out at four different stages of the harvest: before measurement and threshing of the harvest, after threshing but before measurement of the grain, after the measurement of grain, and finally from the revenue after the cultivators have taken their share. The Sutantira Tittam and Merai Chattam leaves give the sharing pattern at each stage separately.

| Preface | vii |

| Blessings of Acharyas (in English Translation) Sri Jagadguru Sankaracharya of Kanchi kamaksi Pitham | xi |

| Sri La Sri thandaimandala Adheenam | xiii |

| Foreword (in English Translation Dr. Kadir Mahadevan, vice Chancellor, Tamil University, Thanjavur | xvii |

| Introduction | 1 |

| The Changalpattu Survey 1767-1774 | 1 |

| The English Archival Records | 1 |

| Survey Districts and the Region | 2 |

| Tamil Palm-leaf manuscripts | 2 |

| Scripts and symbols | 4 |

| Sections and divisions | 4 |

| Chengalpattu Society and Polity | 5 |

| Land Use Pattern | 6 |

| People and their Occupations | 7 |

| Agricultural Production and Productivity | 8 |

| Maniyams and Grain Allocations | 9 |

| Locality and the larger Polity | 10 |

| The Localities | 11 |

| Thirupporur: A cultural capital of the Region | 11 |

| Vadakkuppattu: Producing and Sharping in Abundance | 12 |

| Tamil Locality Accounts for Thirupporur and Vadakkuppattu | 13 |

| Formate of the Accounts | 14 |

| Tarappadi Vagai Edu | 14 |

| Production and Revenue Accounts | 16 |

| Tugai Edus | 19 |

| Accounts of Thirupporur and Vadakkuppatu | 21 |

| Land Utilisation | 21 |

| Households | 23 |

| Agricultural Production | 27 |

| Calculated Revenue | 27 |

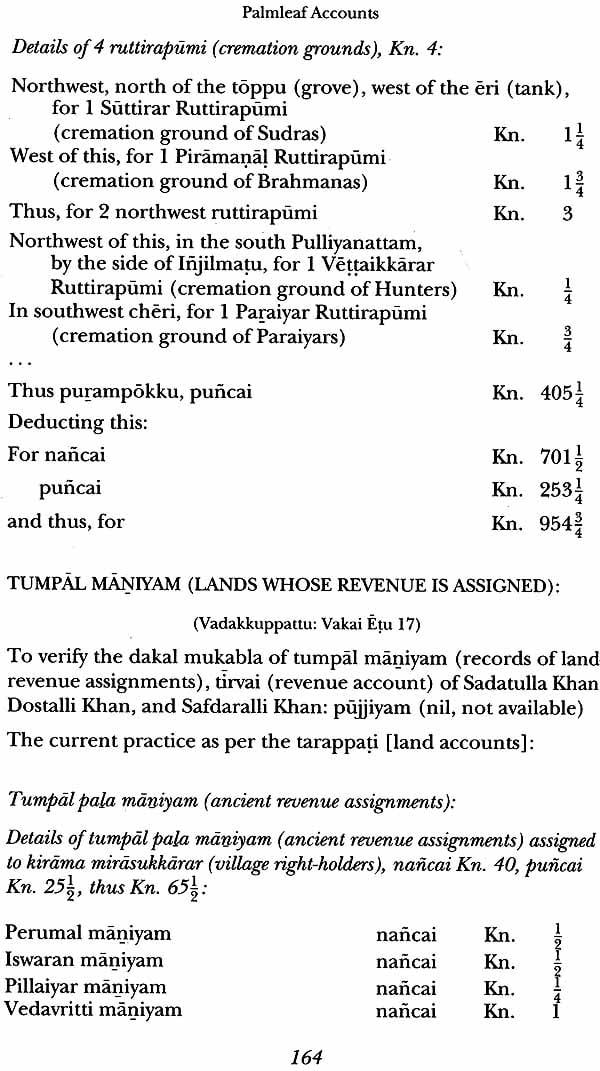

| Maniyams | 34 |

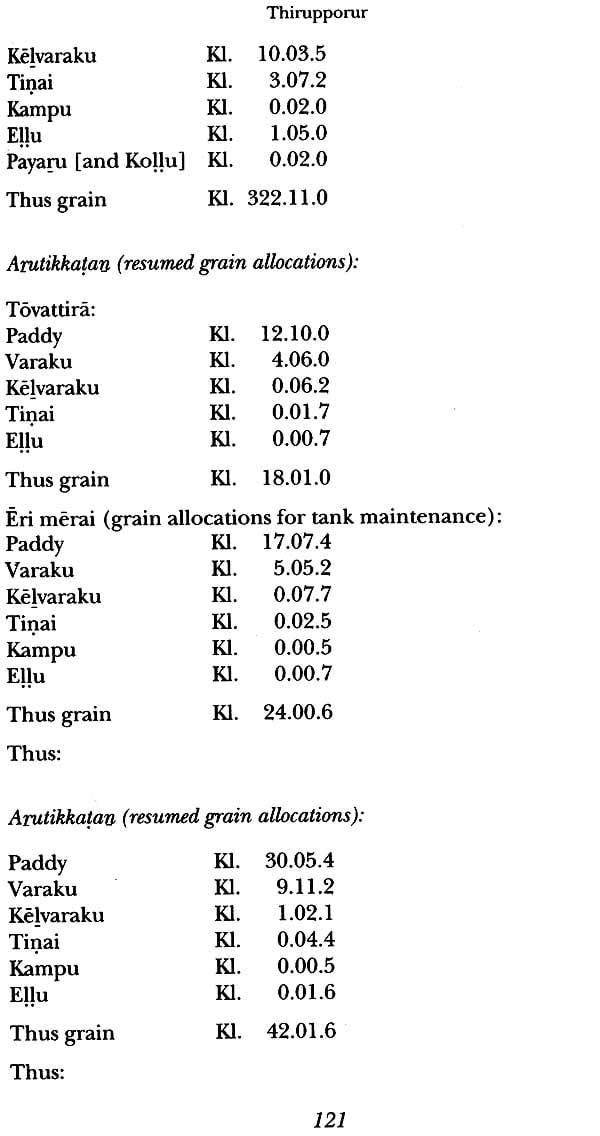

| Grain Allocations | 37 |

| The Locality Budget | 40 |

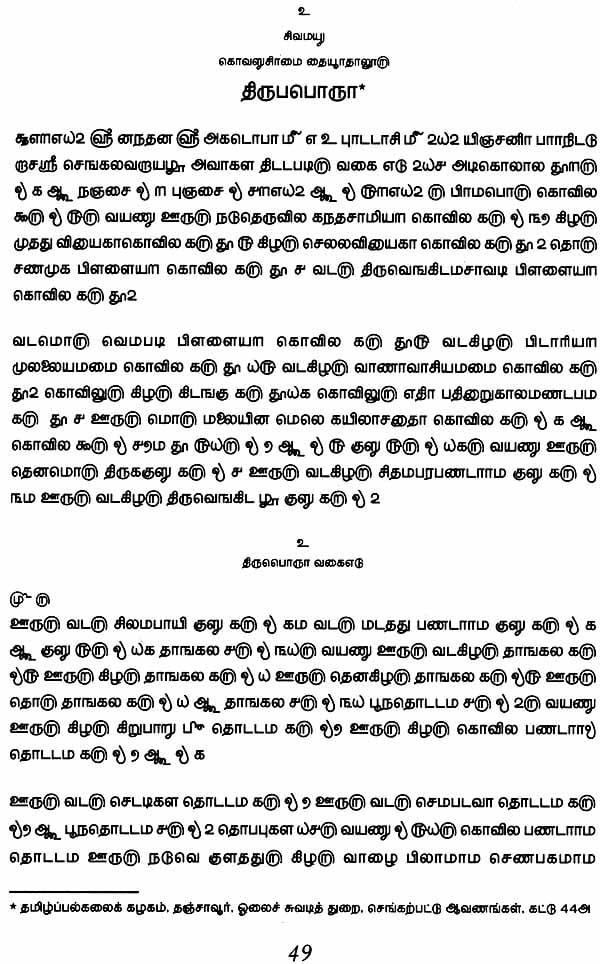

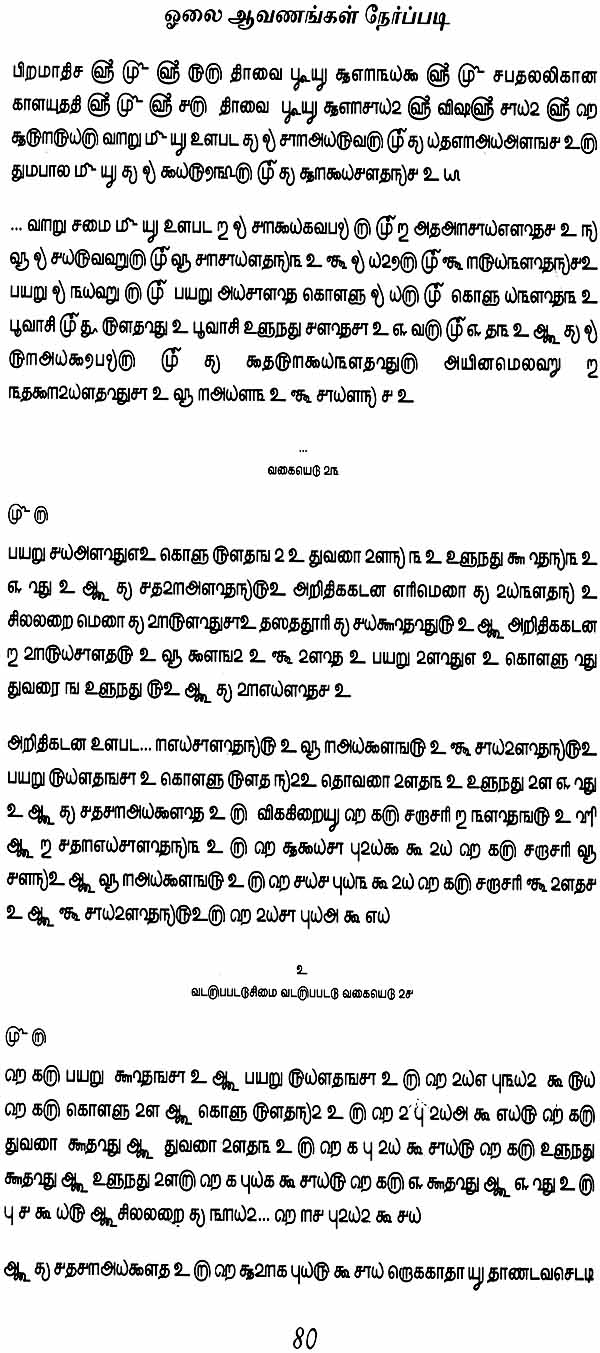

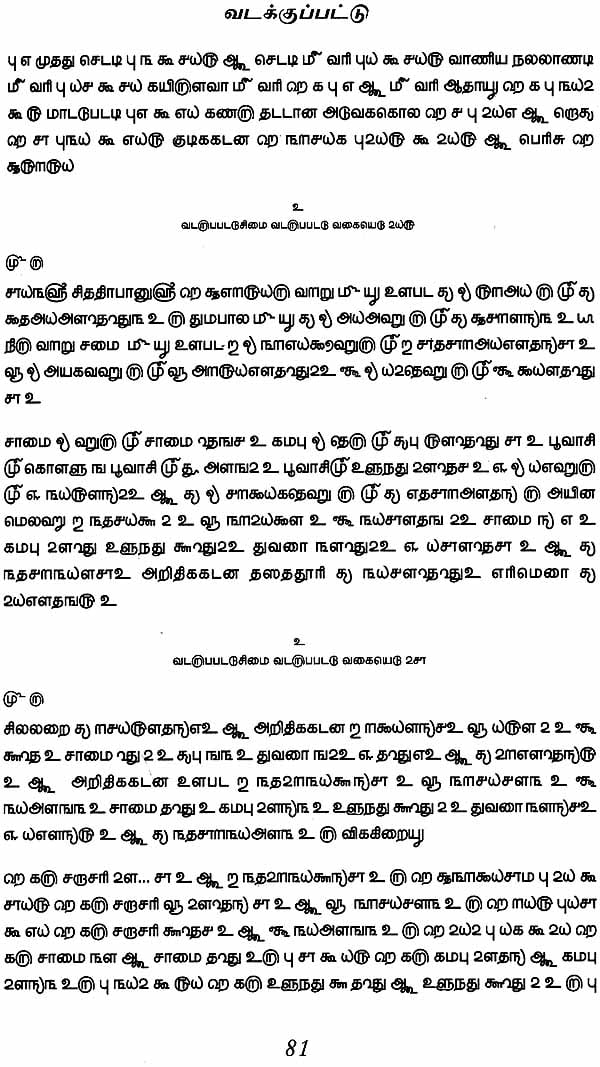

| Tamil Palm-Leaf Accounts (In old Tamil Script) | 45 |

| Thirupporur: A cultural capital of the Region | 49 |

| Vadakkuppattu: Producing and Sharping in Abundance | 72 |

| Palm-Leaf Accounts (English Tanslation) | 87 |

| Thirupporur: A cultural capital of the Region | 89 |

| Vadakkuppattu | 150 |

| English Summary Accounts | 187 |

| Thirupporur | 189 |

| Vadakkuppattu | 196 |