The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali with Insight from the Traditional Commentaries

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAF991 |

| Author: | Edwin F. Bryant |

| Publisher: | North Point Press |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 9789386215567 |

| Pages: | 665 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 610 gm |

Book Description

Edwin F. Bryant’s translation of and commentary on Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras set a new standard for readers interested in one of the most important classical texts of Eastern and world thought.

Written almost two millennia ago, Patanjali’s great work focuses on how to attain direct experience and realization of the purusa: the innermost individual self, or soul. As the classical treatise on the Hindu understanding of mind and consciousness and on the technique of meditation, it has exerted immense influence over the religious practices of Hinduism in India and, more recently, in the West.

Bryant presents each sutra in Sanskrit text, in transliteration, and in precise, clear, direct English translation. His authoritative commentary, drawing insights from the primary classical commentaries written on the sutras over the last millennium and a half, conveys the meaning and depth of each sutra to Western readers in a user-friendly manner but without compromising scholarly rigor or traditional authenticity.

“Bryant impressively succeeds in communicating the essentials of Yoga philosophy and practice to the thoughtful but nonspecialist general reader. His book will surely be welcomed by both serious scholars and responsible practitioners.”

Edwin F. Bryant received his Ph.D. in Indology from Columbia University. He has taught at Columbia University. He has taught at Columbia University and Harvard University and since 2001 has been professor of Hindu religion and philosophy at Rutgers University. Bryant has written numerous scholarly articles and published five previous books, including a translation of the four thousand verses of the tenth book of the Bhagavata Purana called Krishna: The Beautiful Legend of God. In addition to his work in the academy, Bryant teaches workshops on the Yoga Sutras and other Hindu texts in yoga communities around the world.

I congratulate you on your lucid commentary on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. I have appreciated your commentary quoting the traditional commentators Vyasa, Vacaspati Misra, Sankara, Bhoja Raja, Vijnanabhiksu, and Hariharananda, and it reads well. You have presented it in simple and fluent language, which I am sure will be easily understandable to readers. As you are dedicating it to the teachers of yoga, I am sure your book will provide the readers with plenty of knowledge so that they may grasp the philosophy behind the subject and move toward the higher aspects of life in their sadhana (practice).

Patanjala Yoga is a practical subject and not a discursive one. As each individual is electrically alive and dynamic, so yoga is a living, dynamic force in life. in order to savor its essence, one needs a religiously attentive dynamic practice done with awareness and absorption. The life of man is not only the conjunction of prakrti (the sheaths of the body) and purusa (the soul), but alos a combination of these two. Yoga is a means to utilizing the conjunction of prakrti and purusa for freedom and beatitude (moksa), as the two are interwoven and interrelated.

Patanjali explains the practice of kriya-yoga in sutra I of the sadhana pada, repeating the same ingredients as are found in the niyama disciplines, namely tapas, svadhyaya, and Isvara-pranidhana (discipline, self-study, and devotion to God). This three-tiered definition clearly indicates the paths of karma, jnana, and bhakti. Though Patanjali advises bhakti in the beginning of the text in I.23, I consider the disciplines of yama and niyama (II. 30-45) as corresponding to karma-marga (the path of action); asana, pranayama, and pratyahara (II. 46-55) as corresponding to jnana-marga (the path of knowledge); and dharana, dhyana, and samadhi (samyama, III. 1-4) as corresponding to bhakti marga (the path of devotion).

Prakrti and purusa being interwoven and interrelated, the practitioners of yoga have to understand this relationship clearly and perform svadhyaya in the form of asana, pranayama, and pratyahara. Sva means “self” and adhyaya means “study.” These three aspects of Patanjala Yoga lead the sadhaka (practitioner) to understand himself or herself from the skin to the self. Hence, this guides on the path of jnana. Dharana, dhyana, and samadhi being the effect of jnana earned through the practices of asana, pranayama, and pratyahara along with yama and niyama, then lead the sadhaka toward the path of bhakti. Bhakti is the summum bonum of Patanjala Yoga. But if the sadhaka abuses the sadhana with selfish motives, he or she ends up with only the joys of sensual pleasure (bhoga).

As yoga is a lively subject, interpretations of the sutras may vary according to dharma, laksana, and avastha parinama (character, qualities, and conditions) in sadhana (III. 13). Therefore, I differ from the traditional commentators on two things. The first pertains to the effects of asana: tato dvandvanabhighatah (II. 48). The entire text speaks of the intelligence of nature and the intelligence of the self. I understand that the perfection of asana brings unity between the various sheaths of the body and the self (purusa), which Lord Krsna calls ksetra-ksetrajna yoga in the Bhagavad Gita (XIII. 1ff). hence, perfection in asana means a divine union of prakrti with purusa.

The practice of asanas develops sattva guna, sublimating the gunas of rajas and tamas. The aim of asanas is to make the prana (cosmic universal force) move concurrently with the prajna (insight) of the self on its frontier. This means to make the awareness of the self (sasmita) move and cover the entire body (II. 19) so that the mechanisms of nature are sublimated and the intelligence (prajna) of the self engulfs the body with its sukti.

The second point pertains to the virama pratyaya of verse I.18 (virama-pratyayabhyasa-purvah samskara-seso nyah-the other samadhi is preceded by cultivating the determination to terminate [all thoughts]. [in this state] only latent impressions remain). Patanjali himself does not call this other state asamprajnata-samadhi (I. 46). He has said that it is part of sabija-samadhi (I. 46). The various commentators infer this state to be asamprajnata, and this may be because Patanjali mentions samprajnata-samadhi in the preceding sutra. For me, this sutra is referring to a consolidating state of samprajnata samadhi, after attainting which the yogi can move toward asamprajnata (nirbija) samadhi. Hence, this state acts as the intermediary state for nirbija-samadhi. Just as pratyaahara in astanga-yoga (II. 54) is a consolidation stage, where one needs to integrate the external sheath (bahiranga) with the innermost sheath (antaranga), so is the case with the stage of virama pratyaya, for which Patanjali has not coined any term. It is a consolidating stage of Sabina-samadhi, after which the yogi naturally moves toward nirbija-samadhi.

For me, the state of pratyahara in astanga-yoga and virama-pratyaya in samadhi are the touchstones in understanding the purity, clarity, and maturity of prajna, intelligence. When this illuminative and luminous intelligence takes place, the union of prakrti with purusa happens (sattva-purusayoh suddhi-samye kaivalyam iti III.56*). Even in this pratyahara state of astanga-yoga and virama-pratyaya state in samadhi, if one neglects sraddha, virya, smrti, samadhi-prajna (faith, vigor, memory, and the insight of samadhi, the four legs of yoga in I.20), then, even if one has reached the zenith, one is bound to become a yoga-bhrasta, a fallen yogi. Therefore, the practice of pratyahara in astanga yoga or virama-pratyaya in samadhi is to be performed with these four legs of yoga so as to maintain and retain that state of seasoned wisdom (rtambhara prajna, I.48) that consecrates citi-sakti (the power of purusa). It is this combination only that leads the yogi toward the highest state in bhakti-marga-the saranagati-marga-total dependence on Isvara, God. This is how I understand and practice the astanga-yoga of sage Patanjali.

Having expressed my feelings, I am sure your good work and expressions, using the attributes of all the earlier commentators on the Yoga Sutras, will turn out as a study book for hundreds and hundreds of students who have embraced the subject in the West in knowing the light of that hidden illuminative intelligence on the inner self, the atman, and making that light surface and active in their sadhana, which will help their fellow beings experience this unalloyed and untainted bliss with its stream of virtuous (silata) wisdom.

With all my best wishes, I am sure this volume will benefit yoga sadhakas and spiritual seekers throughout the world.

| Foreword by B.K.S. Iyengar | ix | |

| Sanskrit Pronunciation Guide | xiii | |

| The History of Yoga | xvii | |

| Yoga Prior to Patanjali | xix | |

| The Vedic Period | xix | |

| Yoga in the Upanisads | xxi | |

| Yoga in the Mahabharata | xxiii | |

| Yoga and Sankhya | xxv | |

| Patanjali's Yoga | xxxi | |

| Patanjali and the Six Schools of Indian Philosophy | xxxi | |

| The Yoga Sutras as a Text | xxxv | |

| The Commentaries on the Yoga Sutras | xxxvii | |

| The Subject Matter of the Yoga Sutras | xlv | |

| The Dualism of Yoga | xlv | |

| The Sankhya Metaphysics of the Text | xlvii | |

| The Goals of Yoga | liii | |

| The Eight Limbs of Yoga | lvii | |

| The Present Translation and Commentary | lix | |

| Chapter I : | Meditative Absorption | 3 |

| Chapter II : | Practice | 169 |

| Chapter III : | Mystic Powers | 301 |

| Chapter IV : | Absolute Independence | 406 |

| Concluding Reflections | 461 | |

| Chapter Summaries | 475 | |

| Appendix: Devanagari, Transliteration, and Translation of Sutras | 477 | |

| Notes | 507 | |

| Bibliography | 555 | |

| Glossary of Sanskrit Terms and Names | 563 | |

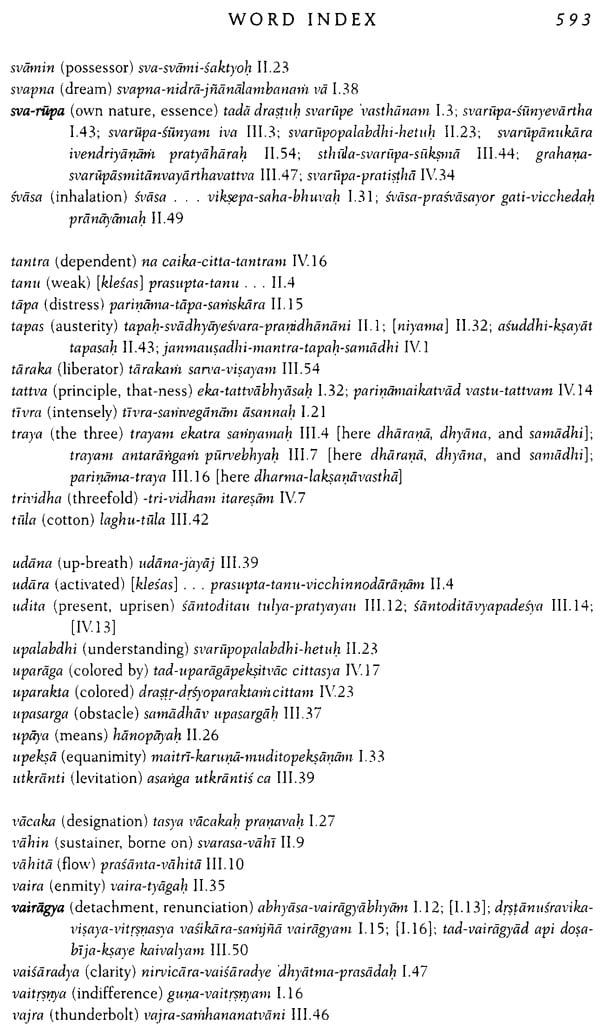

| Word Index | 579 | |

| Acknowledgments | 597 |