Folktales of Lakshadweep ( Set of Two Volumes)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAU440 |

| Author: | M. Mullakoya and Vasanthi Sankaranarayanan |

| Publisher: | Sahithya Akademi, Chennai |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2019 |

| ISBN: | Vol-1 : 9789389195590 Vol-2 : 9789389195583 |

| Pages: | 152 ( Throughout Color Illustrations ) |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 250 gm |

Book Description

The Lakshadweep islands are often described as lamps hung in the gateway to India. They are 36 in all, including the 10 inhabited islands, 17 uninhabited islands, 3 reefs and 6 submerged sand banks. They lie, one after the other, almost parallel to the west coast of Kerala, at varying distances, ranging from 250—450 kms. The southernmost island, Minicoy, is in the longitude of Thiruvananthapuram and the northernmost island, Chetlat in that of Mount Ezhimala. The other islands lie in between.

Much research has not gone into the history and tradition of the people of these islands. Yet it can be understood that people from the Kerala coast migrated to them in the background of the renowned Spice Trade that existed between Kerala and West Asian countries. The first Settlers were mostly Buddhists. They later embraced Islam. The language they speak in different islands show dialect differences. But all the dialects represent a period when ancient Tamil prevalent in Kerala was transforming into the modern day Malayalam. With their language, costume, food habits and other ingredients of culture, they resemble villages in Kerala; except in one island (Minicoy) where the language and traditions are different. They show a close affinity to the people of the island Republic of Maldives.

More than anything else, various types of music and dance had played a major role in keeping alive social life on the isolated islands, which would have otherwise been prosaic and monotonous. There existed greater cooperation among the people and every work was carried out with participation of one another. The accomplishment of music and dance formed an integral part of all such works. The boat building tradition can be taken as a typical example. Oppana songs by women and folk dances by men were organized to mark the progress of work. On completion also, all types of festivities were arranged and the boat pulled on to the sea, with people singing in chorus.

The islanders are hard working. After the day-long engagements related to cultivation and fishing, they reposed in the night by singing and dancing either on the sandy beaches or inside mosques which purified them mentally and prepared them for carrying out various tasks with greater cheer and enthusiasm, the next day. Another pastime during the night hours was story-telling. These were mainly of two types, one narrated by grandparents and elders at home and the second by friends and grand old story-tellers in the assembly of the youngsters. There are hundreds of such short and long stories on each island.

But in the recent past, the story telling tradition met with a sudden halt due to the change in the lifestyle of the islanders, triggered by the introduction of television and other electronic media in the territory. The island natives are now found sitting in front of the television screen enjoying various serials and other programmes instead of listening to the old and imaginary stories from the elders. As a result, many of the stories that existed through word of mouth from one generation to the other are quickly vanishing.

At such a time, earnest efforts are being made to recapture and record the stories to revive the culture of the golden past. I had published in Malayalam, two separate titles, one in 2000 by DC Books, Kottayam and the other in 2001 by the State Institute of Children’s Literature (SICL), Thiruvananthapuram. The stories in the first book are comparatively smaller in size, and are prevalent among the young children of different islands and the second set of longer size, among the youth. They were not serious narrations but a means to spend time joyfully. However, moral lessons can be seen behind each of these stories. Even today The Lakshadweep islands remain crime free and instances of violence are negligible.

Dr. Vasanthi Sankaranarayanan is the translator. She had visited our island in 2002. Her feelings about the stories are also given. I express my sincere gratitude to her.

Needless to say, this is the first attempt to publish the folktales of Lakshadweep in English in a book-form so that the readers can come to know about the literature and people of the far-flung island territory of India.

Dr. M.N. Karassery and Dr. M.M. Basheer had written the introductions to my books in Malayalam. I am of the opinion that their detailed study and critical analysis of the stories would help the readers understand more about the story telling culture and tradition of the islanders. I owe a great deal of respect to them and also to Sri A.P. Kunhamu who translated their writings to English.

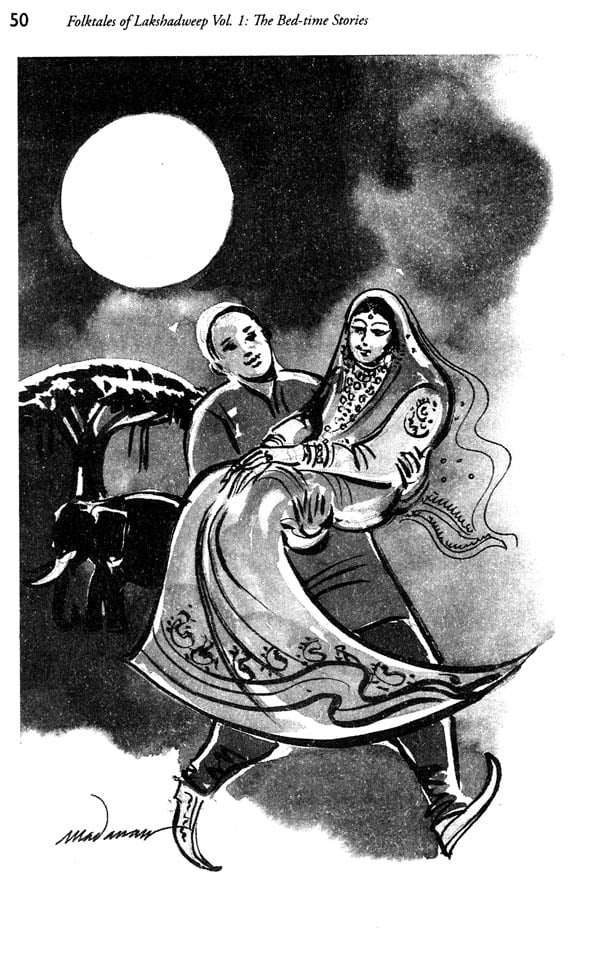

I also owe great respect to the officials of the central academy and also to the Malayalam Board Members, its Convener Sri Prabha Verma and others who have greatly helped me in bringing out this book, which -has been beautifully illustrated by Sri Madanan, Chief Artist of the Mathrubhumi Publications in Kerala.

Lastly, I extend a warm thanks to Ms. Divya of Starnet computers, Kozhikode who had taken all the care to get me the manuscript typed.

During the last Onam season, I was in Kavaratti, the capital island of the Union Territory of Lakshadweep. That was a short stay. Yet, the peaceful deportment of the island inhabitants attracted me much more than the scenic beauty of the island. Away from the din and bustle of city life, this island lies inside a lagoon that resembles a bright girdle, around its waist. The lagoon is after all a natural creation protecting the island from the wrath of the sea. In their colloquial language, it is referred to as ‘Billam’. The islanders characterize the serenity of the Billam, rather than the splendour of the turbulent sea around them. In the daylight, the Billam is seen with a smile of sparkling waves, hiding in its abyss of bluish green seawater, corals of different shapes and sizes and curious tiny fish in myriad colours. What a captivating sight! Did the islanders learn lessons of serenity from Billam or the other way round? Who knows?

The peace-loving islanders do not indulge in crimes like theft, manhandling, robbery and murder. When I came to know that though there is a prison in the capital, constructed years ago, it has not been inaugurated still, for want of even a single prisoner, I just visited and returned.

It seems to me that it is the pure human nature within their hearts, and not the geographical structure that keeps this quiet society (engaged in fishing, collection of pearls, coconut cultivation and coir making out of coconut husks) in the form of an island.

It is the violence, revenge and murder found in these bedtime stories recited in various islands of the group, though with slight variations, remind me of the above experience. Even cannibals have been presented as characters! Seven out of the twelve stories contain murder. Perhaps the islanders may be getting rid of the criminal tendencies lying hidden in their mind through such narrations. I expect that anybody who reads this book will get an intimate understanding of these good neighbours, though in a limited measure. The readers cannot easily forget the wonders of nature (The Child and the Tree), the happiness that follows sorrow (Rice-cake frying pan), mischiefs (The Sky root and the Sprout of the Grinding Stone, The Clever Thief), the superman concept (The Big Belly Button) and the deep affection among siblings (Kokathi Umma) that are depicted. Just as the blunders committed by thieves and priests, the pungency of explicit and implicit social criticism expressed in these stories too, end up as an exploding laughter. Pearls of sweet humour and shells of childlike imagination can be seen scattered on this seashore.

The desire to tell and hear stories is a part of human nature irrespective of time and space. Whether it is the top of the Himalayas or the depths of the Arabian Sea, this human desire remains unchanged. This anthology of folk-tales that has come to the mainland from the Lakshadweep archipelago is a new example of this historical truth. Here we have a dozen folk-tales told and retold by different groups of people belonging to the Union Territory, from generation to generation. Now it is transferred from the island of spoken word to the continent of written text. Before appearing in book form, most of these tales have attracted Malayalam readers when they were published in the Mathrubhumi Weekly and other periodicals. We have been sending these types of books to the Lakshadweep islands for so many years and now such a book is being brought out from the islands to the mainland.

We have several books dealing with the geographical details, social characteristics, customs, peculiarities of language and narrative songs written in English and Malayalam by native authors as well as by those who stayed there as employees. But an anthology of folk-tales revealing the ancient tradition of the islands is something new. Another notable feature about this book is that the sea appears as a very prominent character in almost all the tales.

Like folk-tales everywhere, these stories also look upon life with awe. The wonders of nature are depicted with all the glory and glitter. The human cruelties are despised and the tender feelings are praised. Moral lessons useful to the present and coming generations can also be seen.

The compiler of these tales has told me about the practice of the islanders assembling on the seashore during nights after their prayers and supper. Women and children are also present in these gatherings.

A wide stretch of sand resembling sugar granules; the soothing breeze coming from the sea; the moonlight spreading far and wide; coconut trees waving their heads in tune with the breeze. Wherever you look you find the ‘Billam’ like a girdle round the sea. The baritone song of the Arabian Sea serves as a background note for this beautiful setting.

In the light of the lantern, somebody opens a book of Mapila songs and one or two among them start singing. Someone else explains the story of the song. All others listen intently to the song and the story. Some of them are tempted to join the singing.

On another day instead of singing somebody tells a story. This is usually done by youngsters. Most of the stories are the ones heard from their ancestors. Stories heard from the mainland also are chosen at times. However, these ‘imported’ stories are presented with modifications suited to the island. In addition to these, stories born of the imaginative minds of the narrators are also presented occasionally. That is how these stories got the name ‘Bed-time stories.’

Arabian Tales are supposed to be stories told by the beautiful damsel Shaharasada to Sultan, Shahariar. She was afraid of her death in the next morning. So, she went on telling stories. In one of her stories, ‘Aladdin and the wonderful lamp’ the Dyin saves Aladdin and the princess, a second time. As the dawn approached, she abruptly stopped her narration. Then, there was a conversation between her and the Sultan, as under: Sultan : How many stories do you know? Shaharasada : I can go on telling stories for 1001 nights. Sultan : So it will suffice for extending your life for two years and nine months. What will you do afterwards? Shaharasada : Then I will make new stories. Sultan : If so, do you mean that I will not be able to kill you? Shaharasada : Do you actually want to kill me? Sultan : No, not at all.

Shaharasada could understand that her life had been out of danger. The sultan had started loving her. So without fear, she went on telling stories. Behind each story, narrated on each night, there had been a definite purpose. That was to enable her to live on the next day. Thus the episode continues. Eventually, the sultan’s mind changes. She could save herself and all other girls of the country who were supposed to be killed by the crazy misogynist Sultan.

Oral folk tales of Lakshadweep, compiled by Dr. Mullakoya are felt as a continuation of the Arabian Tales, with an exception. Here the context and characters are different. The islanders toiling from dawn to dusk, usually assembled at their seashore for taking rest at night. While doing so, they were in the habit of telling stories. These stories took them to experiences of suffering, agony, humour and hilarity. It is a sojourn through the worlds of fact and fancy. In this journey, they mustered energy and made themselves liberated from mortality. After all stories, by and large, are attempts for escaping from the inevitable experience of death.

‘Father’s Halal Ship’ and ‘The Angel of Death’ are the two main stories included in this anthology. Both are brilliantly penned fantasies. They unfold the challenges, sufferings and basic instincts for escaping from the experience of death and the destiny of every man which he is compelled to undergo. These tales have the strength and capacity to stand at par with the stories of Mahabharata or the Arabian Tales (1001 nights).

In the ‘Father’s Halal Ship’, the climax emerges through a story within the story. The protagonist, a small boy, is a seeker of truth. He had participated in a story-telling competition pretending to be an old man. He wore a cap, gifted by a witch, due to the magic spell of which, he appeared to be an old man. The old man narrated his own story. It was about a dispute between the king and the queen. Looking at a strange object which appeared in the distance, the king said that it was a fragment of a cloud; but the queen argued that it was a forest animal. The king sent his minister to find out the truth. The minister wanting to be in the good books of the king hid the truth and concurred with him. Enraged by it, the king ordered the queen to be abandoned in a forest as punishment for distrust.

She underwent many miseries in exile. Yet, succeeds to survive with the unexpected help from Providence. After years, the minister comes to know about the queen. He takes her to the country but imprisons her with her son. At that time, there arose a problem with the launching of a new ship constructed by the king. The minister uses the child to launch the ship into the sea. He also lifted the anchor with his own hands. The story thus progresses and finally concludes like this: "Poor queen! Even now she is living as a prisoner in the house of the minister." Saying these words the child removes the cap he wore. Soon he was transformed to a boy. The king realized that the boy was his own son. He kills the dishonest minister. The queen and the boy are saved for their agonies. The story here is all-powerful. The entire stories in this collection are narratives of escape from death.