The Forgotten Monuments of Orissa (In Three Volumes)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDJ969 |

| Author: | Bijaya Kumar Rath and Kamala Ratnam |

| Publisher: | Publications Division, Government of India |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1995 |

| ISBN: | 8123003137 |

| Pages: | 1082 (Illustrated) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 10.8" X 8.4" |

| Weight | 3.50 kg |

Book Description

From the Jacket

Bijay Kumar Rath (B. 1949) did his M. A. in History from the Berhampur University, Ganjam in 1970. He joined the Berhampur University, first as a University scholar and later as a UGC Fellow from 1971 to 1974. He joined the State Archaeology Department, Bhubaneswar, as a Curator in 1974.

He has spearheaded the Listing work of unprotected monuments of Orissa with singular devotion and this publication is a culmination of his efforts.

He was associated with editing State Government publications-"The Heritage of Orissa" and "Archaeological Survey Report of Prachi Valley." He is a co-editor of "The Journal of Orissa Research Society", Bhubaneswar. He has also authored "Cultural History of Orissa", "Brick Temples of Orissa" and "Vishnu Sculpture from Orissa".

Introduction

Under the Fundamental Duties, enshrined in the Constitution of India, it is laid down that "it shall be the duty of every citizen of India to value and preserve the rich heritage of our composite culture." Hitherto, the responsibility for such preservation had rested with the Government. Monuments declared to be of national importance are looked after by the Central Government through the agency of the Archaeological Survey of India, and monuments other than those of national importance by the State Governments through their respective Departments of Archaeology. According to the existing legislation, nearly 5, 000 monuments are looked after by the Central Government and approximately 3,5000 by the State Governments. For a country of the size and cultural wealth of India, this admittedly is not a large number. There are still a large number of monuments, which, for various reasons, have remained 'unprotected' and need to be preserved before they are damaged or destroyed either through neglect or misuse, or as a result of developmental schemes. Besides, there are many new buildings and historic quarters which, being less than a hundred years old, do not qualify for protection under the existing legislation and yet are architecturally and aesthetically very important, like those of the colonial period.

The Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (HNTACH), therefore, decided to list all notable buildings, constructed before 1939, which survive in anything like their original condition and have significance in Indian history, architecture, archaeology and culture. In choosing such buildings particular attention has been paid to:

(i) Association with events that have made a significant contribution to the pattern of our history.

(ii) Association with the lives of persons who have made a significant contribution to our history.

(iii) Special value within certain types.

(a) reflecting a distinctive architectural style.

(b) representing the work of a master.

possessing high artistic or aesthetic value.

(d) representing a distinguishable entity.

(e) illustrating social and economic history.

(f) technological innovations.

(iv) Group value as examples of town planning (e.g. squares, terraces, dharmashalas, sarais, baolies, streets.)

These buildings are classified under the following four categories:

(i) Monumental architecture-religious

(ii) Monumental architecture-civic

(iii) Residential buildings and

(iv) Streetscapes and ancient sites.

Of these, the first two categories deal with monumental buildings, massive and imposing, which were used by the community as a whole or by the head of the state or community, and represent typical architecture of the period. The remaining two represent traditional and vernacular architecture, with an added emphasis on environment, neighbourhood, emotional, cultural and historical value and archaeological potential.

In terms of importance, these buildings have been graded into three categories, I,II and III, on the basis of (a) the date of construction (b) the state of preservation and (c) architectural or aesthetic value, considered from the archaeological (cultural), historical and architectural points of view. Buildings of exceptional interest with unique features which must be saved at any cost are graded as I. such buildings are required to be maintained in a state of constant repair, and could be recommended for protection under central or state legislation. Buildings of special interest are graded as category II, while those which do not qualify for permanent retention but are nevertheless considered to be of some importance, historically or architecturally, are graded as III.

Selected photographs have been included in the listing. Since the listing is intended for use throughout the country, the spellings have been standardized as far as possible and are not always strictly based on vernacular usage or Sanskritik transliteration.

In this context, we would like to mention that the information furnished for each building does not claim to be exhaustive, for the scope of the project does not permit in- depth studies. Difficulties were experienced in ascertaining the ownership of buildings since such claims were often found to be conflicting or vague. Similar problems arose in determining the age of the buildings. In the absence of any firm inscriptional evidence or of definitive stylistic considerations, approximate dates, based on information available locally, have been indicated. Further, since the compilation of information on buildings is an ongoing process and reflects the state of the building at the time of listing, the list is not final and is subject to additions, and in some instances, deletions.

The purpose of such listing, apart from it being of interest to students of history, architecture and urban planners is to recommend that the state governments undertake the protection of the listed monuments and include them as a schedule to Master Plans/Development Plans of all cities, and incorporate them in statutory maps. In the absence of any existing legislative protection for these buildings, it is hoped that the civic authorities will undertake responsibility for their maintenance and upkeep against misuse, damage or sometimes even destruction. In fact, some of these buildings could be found suitable for compatible re-use, in consonance with their dignity and original function. The need of the hour, however, is an effective legislation through the Town and Country Planning Acts of the respective State Governments with suitable enabling and requiring provisions for the conservation of historic building, quarters and cities.

Foreword

Orissa has aptly been called the Land of Temples. In early historic times the area was referred to as Odra from which the modern name derives. One can see monuments testifying to the growth of many religions amongst which dominate Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. At a later date, the names Kalinga, referring to the southern coastal part and Utkala, to the northern, more interior part, came into vogue.

Historically, the area came into prominence when, attracted by the fame of its culture and wealth, Emperor Asoka decided to add it to his empire. It was on the road between Bhubaneswar and Puri on the banks of the river, symbolically named "Daya" that the Kalinga battle was fought. A victorious Asoka was witness to the vast numbers of dead warriors along the river bank. In a unique perception the emperor underwent a transformation and accepted the tenets of Buddhism. It was from the coast of Orissa the Noble Truths spread world wide and the Indian traditions traveled all over the South East Asia and Sri Lanka to establish a cultural empire, an event that is still celebrated in Orissa as the festival of Bali-Jatra.

Orissa is unique in that ideas have been permanently transformed into stone. The symbols of that age stand testimony in the monuments of Orissa. There are innumerable temples and monuments in the whole state dating back to the first century BC. Vagaries of nature and vandalism of man has led to degradation of such priceless architecture.

One of the aims and objectives of INTACH is to undertake measures for the preservation and conservation of cultural property of the country that have a high archaeological and historic value so far not protected by the Central and State Statutes. Towards this objective INTACH has undertaken this work of listing of unprotected monuments.

Commendable work has been done by Dr B. K. Rath and his team. Not only will this exercise be of use to scholars and students of history and architecture, but I hope it will enable readers to bring to the notice of the government, State and Central, the sites which are in desperate need of conservation so that they move towards their restoration and protection expeditiously.

Editor's Note

The great tradition of built heritage in Orissa is as old as her recorded history or even older, and it still finds an echo in the religious and cultural life of the odia people even today. For scholars, tourists and laymen Orissa offers its rich and varied archaeological treasures and wealth of monuments in a pristine and, fortunately, intact form. The entire State is dotted with a large number of standing monuments such as early Jaina caves, medieval Jaina temples; Buddhist viharas, chaityas and stupas, Hindu, temples, mathas; mosques; churches, ancient and medieval forts; palaces of erstwhile kings and ruling chiefs and the colonial architecture built during the British rule in Orissa. Numerically Hindu temples predominate over other class of monuments in Orissa.

We do not come across any monument in Orissa which can be dated earlier than the third century BC But, from third century BC onwards, the built heritage is recorded for a period of about twenty - two hundred years. Among these, the temples of Orissa form a class by itself and are famous for their architectural peculiarities. These are known to represent Kalinga School of architecture, Kalinga being one of the names of ancient Orissa.

In conformity with the origin and growth of post Gupta temple architecture in India, we have in Orissa early temples at Mahendragiri, Jaipur, Bhubaneswar and Bankada near Banpur of Puri district. Besides, a number of sculptural and architectural remains are found in the above places which evidently were from early temples in Orissa and which clearly indicate the origin and growth of a separate regional style in ancient Orissa like that of the early Pallava architecture at Mahabalipuram or early Chalukyan architecture at Aihole and early temples in parts of north and central India.

The temple building activities started with the advent of Sailodbhava kings (circa AD 575 to 736). After the Sailodbhavas, the Bhauma-Karas (AD 736 to 1435) ruled successively as masters of the area. Amongst the above four dynasties, the Somavamsis and the Gangas were prolific builders and have left to us a large number of temples. Though temples belonging to different periods dot each nook and corner of Orissa, we find concentration of temples in known religious centers and important places like Jaipur and Chaudwar in Cuttack district, Bhubaneswar, Konark, Puri in Puri district and Ranipur-Jharial in Bolangir district. But Bhubaneswar takes the place of pride in having a large number of extant temples built during all the above dynastic periods and it becomes a unique place for the study of the development of Orissan architecture and sculpture.

In the beginning an Orissan temple in the manner of Gupta temple, consisted of a square sanctum with a sikhara and a rectangular mukhamandapa (porch). The mukhamandapa, known in Orissan temple terminology as jagamohana, had pillars inside it to support the flat roof. We find jagamohana of this type at Niladriprasad, near Banpur and Parasuramesvara temple of Bhubaneswar, dated to seventh century AD.

The pillars inside the jagamohana disappeared gradually in the Bhauma-Kara period, and with the use of the cantilever principle the load of the ceiling was taken by pilasters provided on the inner walls of the jagamohana. In plan it retained the rectangular form but became more restricted lengthwise. The jagamohana of the Vaital, Sisiresvara, Mohini and Markandesvara temple at Bhubaneswar bear evidence to this.

During the period from AD 600 to 950 we also find a gradual transformation in the sanctum proper or the rekha deula. Its exterior plan underwent changes. The earlier temple facades have three vertical sections known in temple terminology as raha paga or the central vertical section and konika paga or corner vertical section as low projections. This resulted in a squarish appearance of the exterior plan of the temple known then as a triratha temple. But with the change in the subsequent periods, the triratha form of the temple plan transformed into the pancharatha temple. The hange was due to the increase in the number of vertical sections on the facades by addition of subsidiary vertical sections called anuratha paga and their bold projection. This resulted in a round-like shape of the exterior plan of the sanctum. In the Ganga period the number of pagas increased and we find saptaratha and even a navaratha plan in the temple at Vakesvara at Bhubaneswar.

Side by side there was noticeable transformation on the elevation profile of the rekha deula. In the earlier stage the sanctum rises from the ground level abruptly and the sikhara gradually tapers inside as it rose in height. By the time of the Somavamsis the tapering is only from the top portion of the sikhara or gandi, and it takes a sudden inward curve to the base of the beki or the neck, below the amalaka.

The Somavamsi period witnessed a formative phase in the temple architecture of Orissa with the introduction of pancharatha plan, the square jagamohana and the division of the vertical sections of the cube of the jagamohana in the manner of the rekha deula. The height of the Jagamohana increased with the introduction of stepped pyramidal roof or pidha deula. Towards the middle of the eleventh century AD both the rekha and pidha deulas are fully developed as evident in the Brahmesvara and the Lingaraja temples at Bhubaneswar. There was also experimentation to go in for higher structures and large temple complexes.

During the rule of Imperial Gangas, who succeeded the Somavamsis, we find two important development in Orissan architecture. The first in the introduction of the plinth. All the temples built during this period have a raised platform making the temples further high.

The second important feature introduced in this period is the addition of two more chambers, natamandira or the dancing hall and bhogamandapa or the offering hall, along the axial plan of the rekha and pidha structures. We find the raised plinth all well as the natmandira and bhogamandapa in the Lingaraja temple, the Jagannatha temple at Puri, the Ananta Vasudeva temple, and the Parvati temple inside the Lingaraja temple complex at Bhubaneswar. But the famous temple of Sun God at Konark has only the natamandira and that too detached from the general plan of the main temple. Generally the natamandira has a flat roof and the bhogamandapa is a pidha structure. The four chambered plan of a temple complex continued and there was no further elaboration on the plan of a temple either horizontally or vertically during the subsequent periods.

As part of the Listing Project the Orissa Regional Chapter of INTACH took up the listing of unprotected monuments and buildings of special interest in the State from July 1987 and completed it in March 1992. A team of four Field-cum-Research Assistants conducted the actual listing, covering all the former thirteen districts of Orissa. The total number of unprotected standing monuments and buildings of special interest listed thus stands at 2706. it has not been possible to cover all the places in each district of Orissa because of various factors although a sincere effort has been made to reach most of the important places. We have also not covered the forts of Orissa which are not found as standing structures.

During the period when the listing work in Orissa was initiated and completed the State had thirteen districts. The number of districts have now increased to 30. These new districts were formed by up-grading the sub-divisions of old districts.

In our publication however', we have followed the earlier thirteen districts which existed at the time of listing. The listing of Orissa is being published in three volumes following the alphabetical order of the thirteen districts. Thus volume I contains list of unprotected monuments of Balasore, Bolangir, Cuttack and Dhenkanal; Volume II of Ganjam, Kalahandi, Keonjhar, Koraput and Mayurbhanj; and volume III of Phulbani, Puri, Sambalpur and Sundergarh districts.

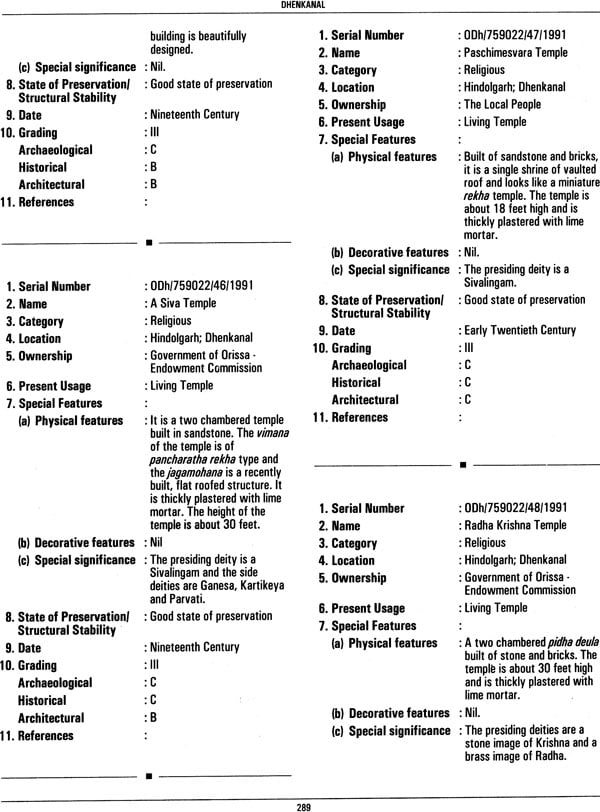

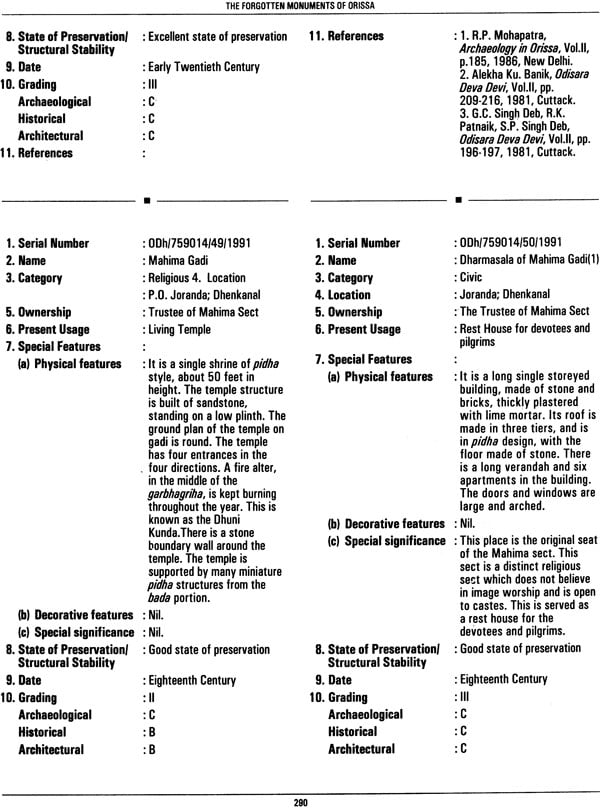

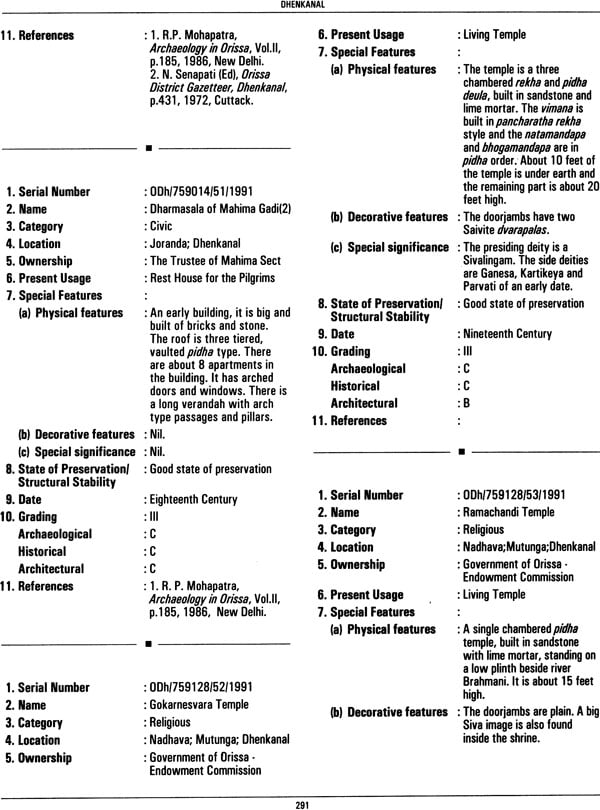

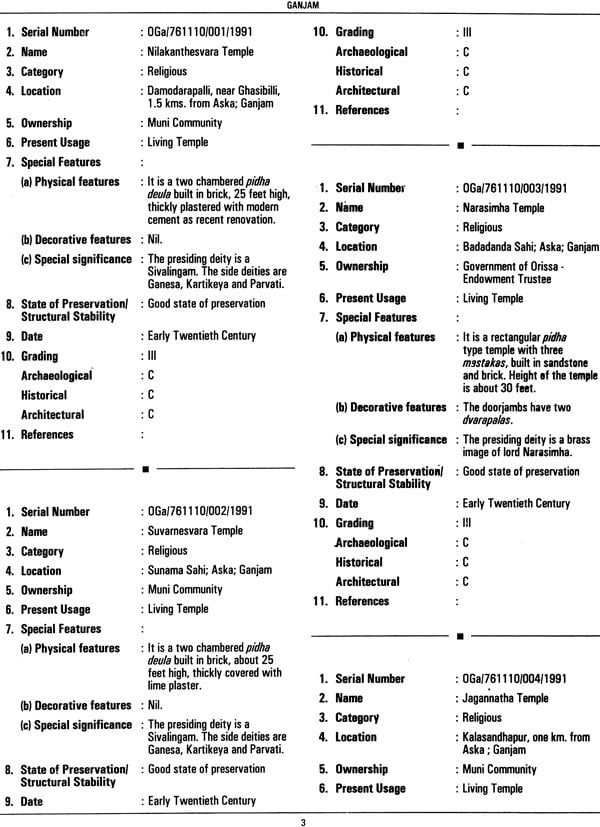

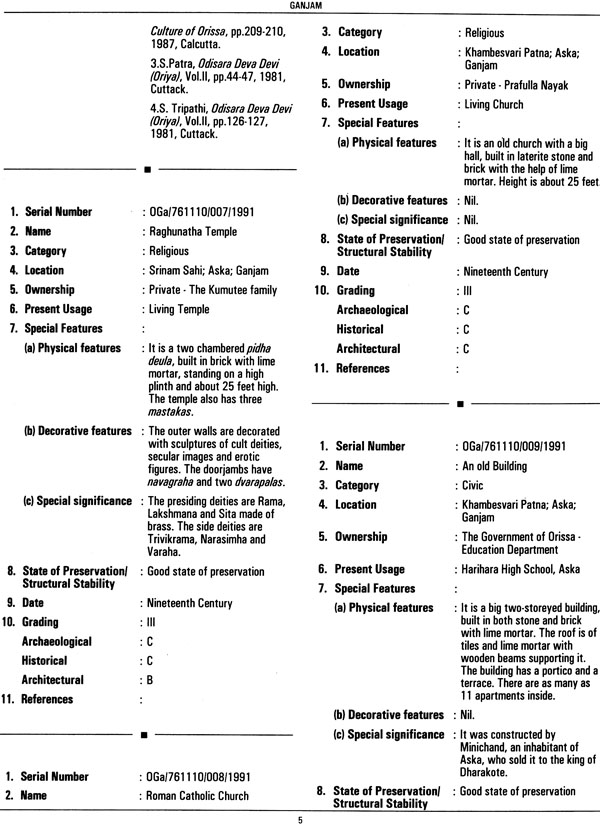

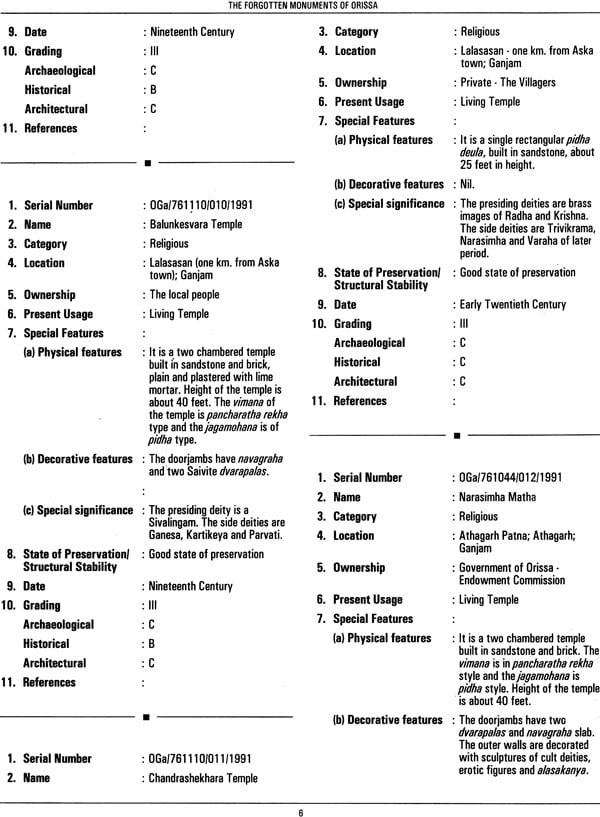

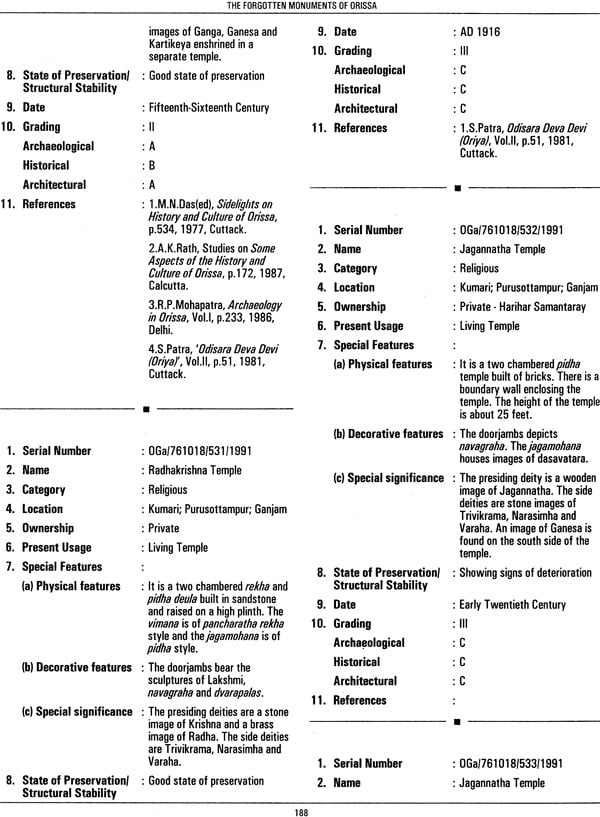

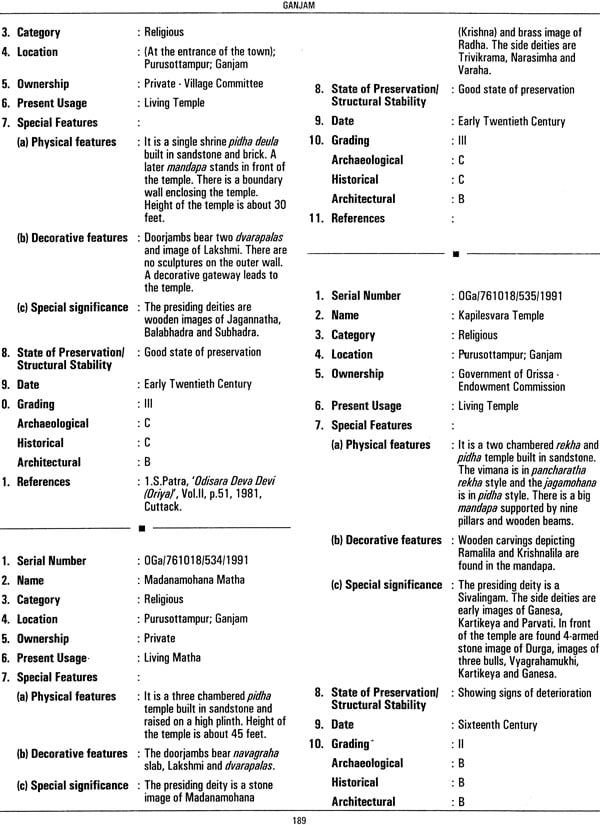

INTACH has formulated a specific format for documentation of these monuments viz. 1. Serial Number 2. Name, 3. Category, 4. Location, 5. Ownership, 6. Present Usage, 7. Special Features, 8. State of Preservation or Structural Stability, 9. Date, 10. Grading, and 11. References. Against the first information column the district, pin code, serial number given to each unprotected monument of that district and the year of listing are given. Under Category, the listed monument is specifically categorized into either Religious, Streetscape, Civil or Residential. Under Location, the details of the village or street/are of the town, nearest town, and districts are mentioned. Under Special Features we have tried to describe the Physical Features, Decorative Features and Special Significance of an unprotected monument thus listed. On the whole we have tried to be brief but specific.

From the listing made in Orissa it is apparent that a large number of unprotected monuments lie neglected in the State. The number of monuments already protected by the ASI and the Orissa State Archaeology is negligible compared to that of the unprotected ones. When the lists of different districts are compared we find that the three coastal districts, viz. Ganjam, Puri and Cuttack, account for a larger majority. There is a historical reason for this. All through her history the political epicenters of the State were located either in the present Puri or Cuttack district. All the major ancient and medieval dynasties such as the Sailodbhavas (AD 575 to 700). The Bhauma -Karas (AD 736 to 940), the Somavamsis (CAD 925 to 1110), the Gangas (CAD 110 to 1435) and the Suryavamsis (CAD 1435 to 1540) had their capitals located either in Puri or Cuttack district. Secondly, the five sacred religious centers of Orissa such as Viraja, Mahavinayaka, Ekamra, Srikshetra, Arka-Kshetra, respectively famous for Shakti, Ganapati, Shiva, Vishnu and Surya worship, are located at Jaipur, Mahavinayaka (Cuttack district) and Bhubaneswar, Puri and Konark (Puri district). Obviously these religious centers and the nearby areas became the centers of built heritage. In Ganjam, a large number of standing monuments of a later period are also found. The other districts, covering the areas of feudatory rulers under the imperial powers of ancient and medieval Orissa as well as the erstwhile princely states, contain monuments of early as well as late periods. Again those places, where the Britishers had their administrative headquarters or commercial links, contain buildings built in colonial style of architecture.

It would not be out of place to mention here that the later temples of Orissa, particularly in border districts such as Balasore, Mayurbhanj, Sambalpur, Sundargarh, Kalahandi, Bolangir and Ganjam, have imbibed traits from other architectural style and one finds a beautiful fusion of Bengali chal type architecture with Orissan architecture in Balasore, blend of Central Indian style and Orissan style in Sambalpur and Sundargarh etc. the palaces, numbering about 50, of the princely states form a special category of built heritage in Orissa.

I am really thankful to INTACH for giving me this opportunity of supervising the Listing Project in Orissa, which wad completed within the scheduled time frame. As already stated earlier, we cannot claim this listing to be comprehensive and final, but it is the first of its kind and will need to be revised and up-dated as further developments take place in the State.

I am equally thankful to the Department of Culture, Government of Orissa for allowing me to help in the editing work of these volumes.

It is hoped that the list would be found to be useful to students and the general public interested in built heritage of Orissa.

| Map of Balasore | 1 |

| Note on Listing of Balasore District | 1 |

| Listing of Balasore District | 3 |

| Map of Bolangir | 49 |

| Note on Bolangir District | 49 |

| Listing of Bolangir District | 51 |

| Map of Cuttack | 117 |

| Note on Listing of Cuttack District | 117 |

| Listing of Cuttack District | 119 |

| Map of Dhenkanal | 271 |

| Note on Listing of Dhenkanal District | 271 |

| Listing of Dhenkanal District | 273 |

| List of Protected Monuments | 299 |

| Glossary of Terms | 309 |

| | |

| Map of Ganjam | 1 |

| Note on Listing of Ganjam District | 1 |

| Listing of Ganjam District | 3 |

| Map of Kalahandi | 207 |

| Note on Listing of Kalahandi District | 207 |

| Listing of Kalahandi District | 209 |

| Map of Keonjhar | 231 |

| Note on Listing of Keonjhar District | 231 |

| Listing of Keonjhar District | 233 |

| Map of Koraput | 247 |

| Note on Listing of Koraput District | 247 |

| Listing of Koraput District | 249 |

| Map of Mayurbhanj District | 313 |

| Note on Listing of Mayurbhanj District | 313 |

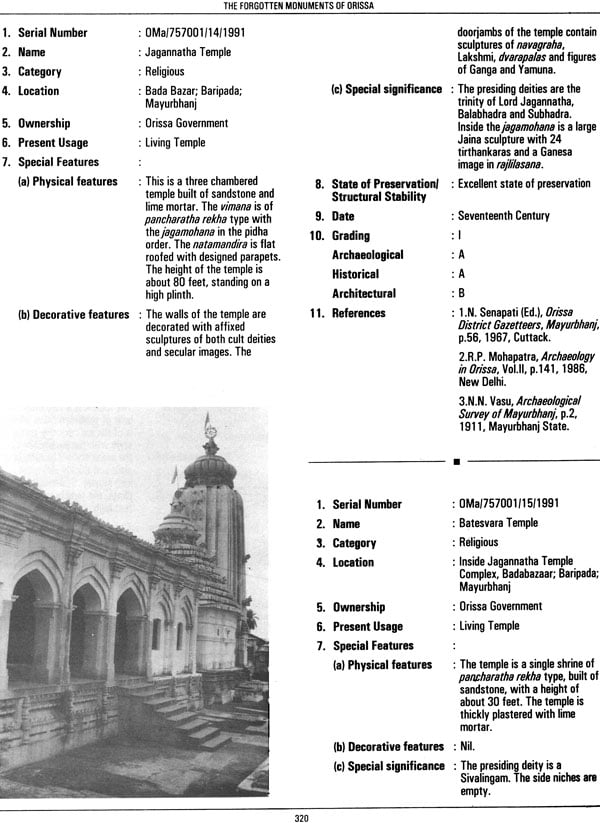

| Listing of Mayurbhanj District | 315 |

| List of Protected Monuments | 339 |

| Glossary of Terms | 347 |

| | |

| Map of Phulbani | 1 |

| Note on Listing of Phulbani District | 1 |

| Listing of Phulbani District | 3 |

| Map of Puri | 19 |

| Note on Listing of Puri District | 19 |

| Listing of Puri District | 21 |

| Map of Sambalpur | 249 |

| Note on Listing of Sambalpur District | 249 |

| Listing of Sambalpur District | 251 |

| Map of Sundargarh | 325 |

| Note on Listing of Sundargarh District | 325 |

| Listing of Sundargarh District | 232 |

| List of Protected Monuments | 347 |

| Glossary of Terms | 359 |