The Problem of Universals in Indian Philosophy

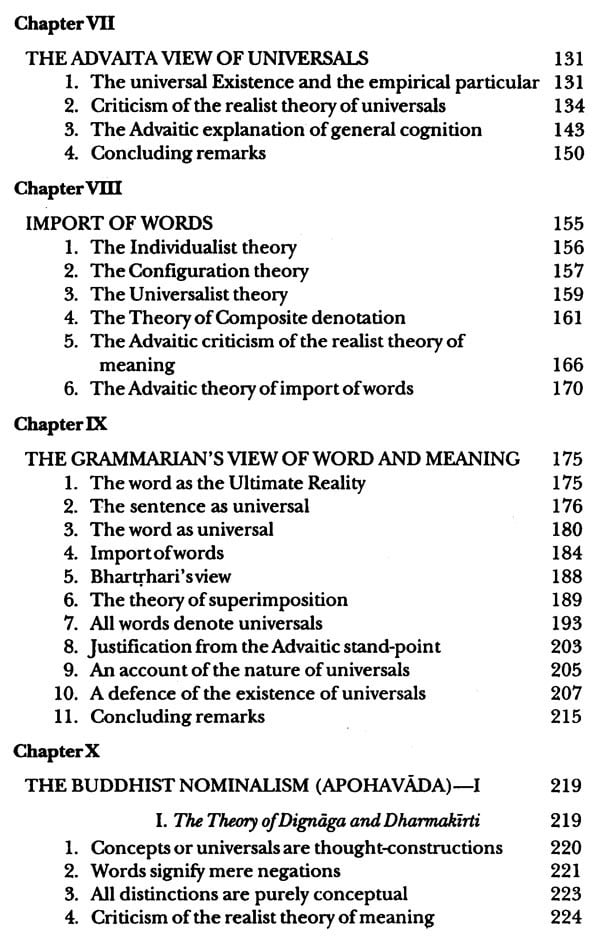

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDD318 |

| Author: | Raja Ram Dravid |

| Publisher: | MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. LTD. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2001 |

| ISBN: | 9788120808324 |

| Pages: | 406 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 Inches |

| Weight | 602 gm |

Book Description

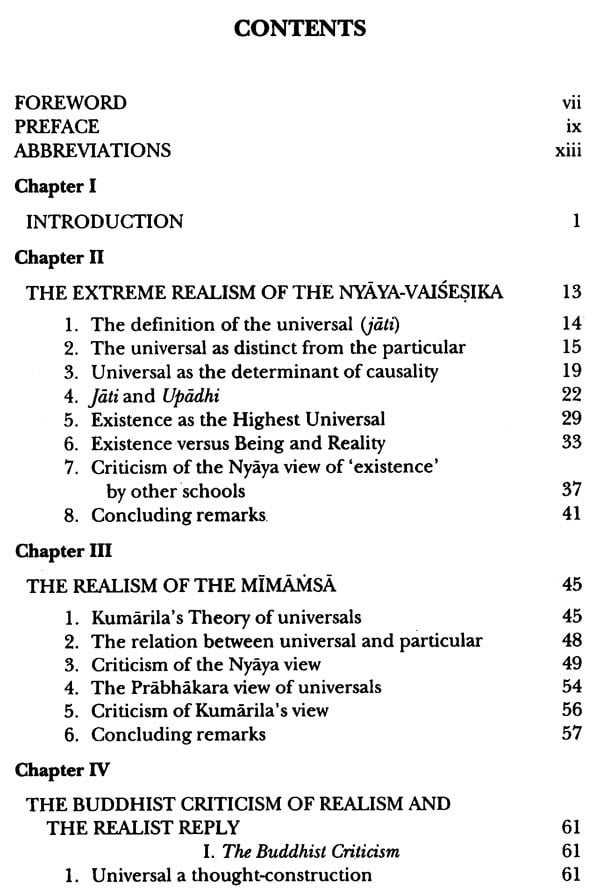

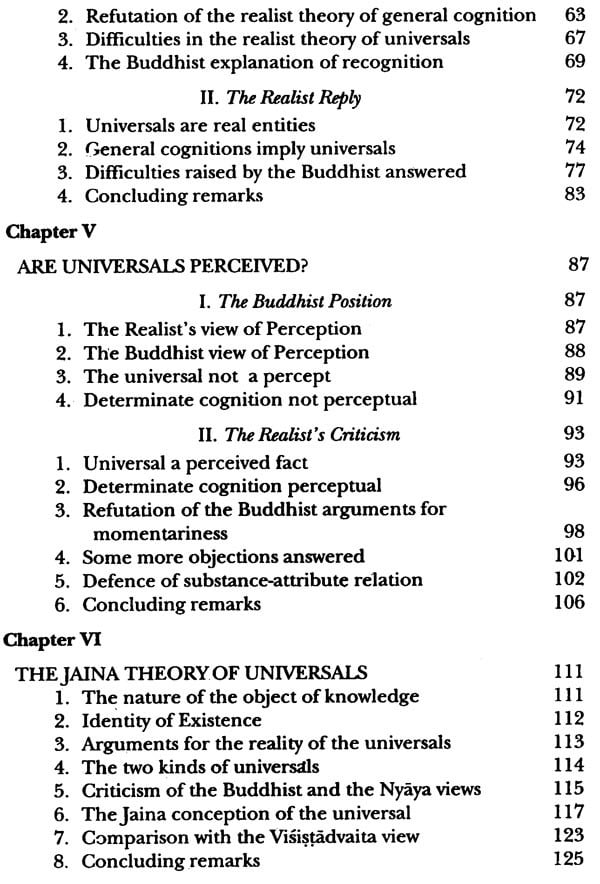

Starting with the Nyaya-Vaiseshikas and Mimamsa Realisms, he goes to the Buddhist, Jaina, Vedanta (Advaita and Visistadvaita) and the Grammarian School of Bhartrhari. The various issues connected with this problem, the nature of the universals, their mode of existence and cognition and connection with words and things, are discussed at length with great analytical skill and insight. The merits and demerits of each point of view are brought out very clearly. I may draw particular attention to the excellent analysis of Buddhist Nominalism (Apohavada) and the views of the Grammar School as instances in this regard.

In writing this book Dr. Dravid has used the texts written by the masters of the different systems, instead of relying, as is generally done, on introductory texts. Again, he has not been content with the stating and examining of views system-wise. He has also treated separately the principal thinkers of each system taking care to show how the doctrines formulated by the different systems evolved, and how, and this is very important, the different masters of each system differed in many important respects. He has amply shown that the different schools are the different attempts to clarify the ontological and metaphysical insight at the root of the different systems.

I have endeavoured in this book to give a critical and comprehensive account of the discussion on universals in Indian Philosophy. I have examined and evaluated the various theories of universals advocated by different systems and suggested in the end a line of approach to the solution of the age-old problem. This in no way is the first attempt to give an account of the problem of universals in Indian Philosophy. Such renowned scholars as Stcherbatsky in Buddhist Logic and Dr. Satkari Mukherjee in The Buddhist Philosophy of Universal Flux and The Jaina Philosophy of Non-absolutism have discussed the problem in some detail. In recent times Dr. D. N. Shastri in Critique of Indian Realism and Dr. G. N. Shastri in Philosophy of Word and Meaning have added a useful discussion on this subject. But the accounts of these authors are limited in scope naturally because the topic of universals forms only a small part of their work. Hence, a comprehensive and critical discussion of this fundamental problem covering all the important theories of universals in Indian philosophy and their mutual conflicts and criticisms, and a comparative study of them with their Western counterparts was very much needed. I have ventured to undertake this task.

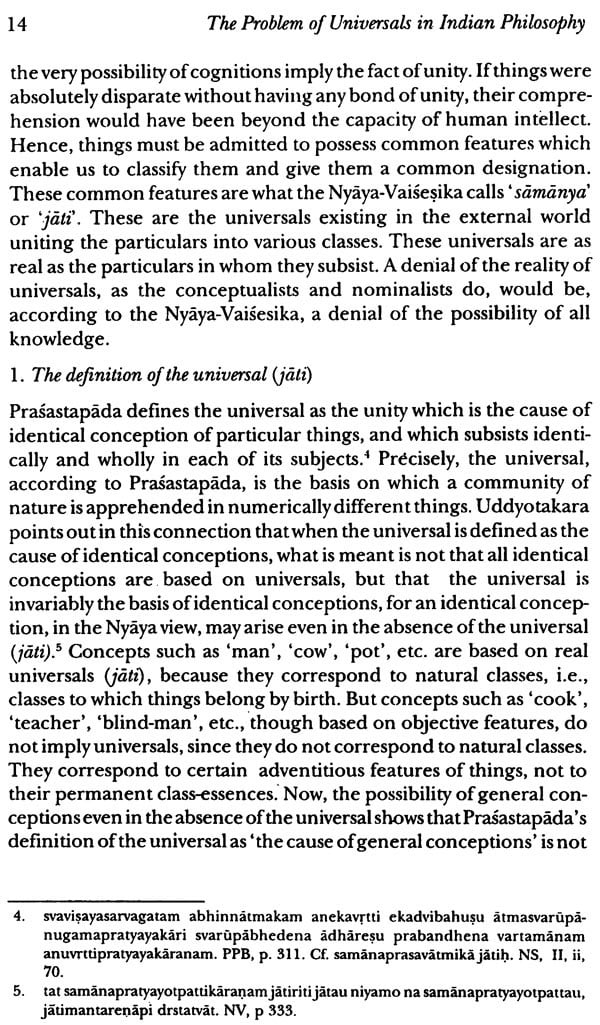

Now the question naturally arises: are these concepts and words true? Do they give us any knowledge of the outside world? Does the universal concept in the mind, or the general word in our language, stand for something that is objectively real? In other words, are there universals just as there are particulars? How are the universals, if any, related to particulars? These and other allied questions have formed the topic of fundamental importance both in Indian and Western Philosophy. It is, indeed, of central importance to inquire as to what is the relation between mental concepts and objective reality. If universal concepts are said to have no foundation in extramental reality, i.e., if they are regarded as purely subjective constructions, then a rift between thought and reality is created.

Book's Contents and Sample Pages