Theology After Vedanta (An Experiment In Comparative Theology)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IHL299 |

| Author: | Francis X. Clooney, S.J |

| Publisher: | Sri Satguru Publications |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1993 |

| ISBN: | 8170303729 |

| Pages: | 281 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.0 inch x 6.0 inch |

| Weight | 430 gm |

Book Description

In two respects this is a truly original book. First it elaborates the fundamental truth that people and communities live from the word of scripture not from doctrines to which scriptures tend to be reduced let alone form hermeneutical theories, applied to scriptures second this book refuses to take a higher view in History of Religious by passing superficially attractive judgments on either Christianity or Hinduism. It does not take side with either dogmatism or liberalism and its impartiality is modest. The author does not attack any side he appreciates compares and then seeks such theological illumination as the process of appreciation and comparison warrants.

The message addressed to catholic theologians deserves careful attention. My hunch is that history or religion scholars some of whom are former Christians with chips on their shoulders can learn a lot about just what kind of commitment is necessary to take non Christian religious traditions seriously.

I think Clooney’s approach holds real promise for interreligious dialogue because it operators form within the setting of encounter between strange and seemingly incompatible worlds. It refuses to adopt for its point of departure an imperious theory about the possible significance that any religion could have. This is an exercise in theological neighborliness not summitry.

Professor of Sanskrit and Indian studies and chair of the department of south Asian languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago.

Francis X. Clooney, S.J. is associate professor in the theology Department of Boston College.

From the Inception of the ongoing toward a comparative philosophy of Religious project at the university of Chicago Divinity school (for basic descriptions see my introduction in volume I- Myth and Philosophy) the organizers and the participants have quite explicitly recognized that the term philosophy is being used in a rather broad sense. Thus everyone who has been involved has accepted the presumption that the term outside the faith commitments associated with particular religious traditions and closely corresponding theological enterprises in which such religious commitments play an explicit role.

In the previous volumes that have been published in the series (Myth and philosophy Mencius and Aquinas) theories of virtue and conceptions of courage and discourse and practice) the term philosophy has been used in this rather broad sense and little explicit references to theology has been made. The only major exception is Francis X. Clooney’s essay Vedanta Commentary and the Theological component of Cross Cultural study which provided a preliminary formulation of many of the ideas that are more fully developed in the present volume (See Myth and Philosophy pp 287-316) at the time Clooney’s quite self-conscious insistence on using the term theology rather than the term philosophy was not called to the attention of readers in any compelling way either by the editors or by Clooney himself. However now that a full length book on Theology after Vedanta is being published in the toward a comparative philosophy of religious series some further comment seems to be in order.

This is not the place to embark on an extended discussion (either descriptive or normative) of the highly complex relationships between related forms of theology. At least one such discussion will be included in an essay that will appear in a collection of essays entitled Religion and practiveal reason that will be published in the series in late 1993. In the Present context a few comments directly related to clooney’s book will have to suffice.

In the present volume Clooney insists on emphasizing the theological character of his study in order to highlight two very important dimensions of his argument. The first has to do with his interpretation of the Indian Advaita (non-Dualist) texts that constitute his most important primary sources. The second has to do with his own intellectual identity and with the closely correlated method of comparative study which he proposes and implements. The issues involved are not minor. They go to the very heart of the highly original and extremely important contributions that Clooney makes to Indological studies on the one hand and to the theory and practice of comparison on the order.

In most of the best known modern scholarship on Sankara and the Advaita tradition in India the emphasis has been placed on philosophy in the narrow sense noted above. Given this intellectual background one of the major achievements of Advaita writings in general and the work of Sankara in particular are thoroughly theological. To be more specific Clooney demonstrates that the Advaita texts(s) are deeply and inextricably embedded in a tradition in which the theological authority of pre-existing Vedic scriptures is strongly and consistently affirmed Clooney goes on to highlighted that fact that the Advaitins in general and Sankara in particular have formulated their teachings and marshaled their arguments in a genre of theological writing that can best be described as commentarial or exegetical.

Working with this specifically theological character of Advaita discourse clearly in mind Clooney develops his own interpretation of the Advaita/ Sankara tradition that is both original and compelling. Using as background his previous studies of the earlier Mimamsa tradition on which Sankara and the later Advaitins built he provides the best available discussion of the content of the Advaita doctrine the character of Advaita soteriology and the style of Advaita argument.

Important as Clooney’s Indological contribution is the most significant breakthrough that he achieves in theology after Vedanta concerns the theory and practice of comparison. Building on the work of Lee Yearley in Mencius and Aquinas, Clooney sets forth and implements his won approach in which he highlights the theological dimension in a way that Yearley did not. Clooney begins with an ongoing tradition of Roman Catholic theology. He then undertakes an intense reading of the Advaita texts(s) that concern him taking seriously into account not only the intellectual content in which they were written but also the kind of involved theological reading that they themselves presuppose and commend. After Clooney’s own theological Orientalism and modes of reasoning have been challenged and enriched buy this process he then proceeds to undertake a new reading of what he considers to be the most comparable text(s) within his own Roman Catholic tradition in this case Thomas Aquinas Summan Theolgine and the commentaries associated with it.

Clooney’s distinctively theological approach is characterized by a very high level of hermeneutical sophistication. His perspective is a modest one in the sense that he neither presumes nor attempts to construct any kind of God’s eye view (or any kind of view from nowhere) that would enable him to arrive at a synthesis between the two texts or traditions that he is comparing or to render any definitive evaluations that would rank either one above the other. What is more the methods that he does use are highly sophisticated adaptations and extensions of the very best contemporary thinking in the area of hermeneutics in general and of reader oriented literary theory in particular.

For theologians who are committed to a particular religious tradition theology after Vedanta opens a path toward a new kind of theology of religions that combines two elements. The first is a perspective that is inclusivist in the sense that it recognizes that potential truth value and soterilogical efficacy of the theological and traditions of others. The second element which serves as an essential complement to the first is a very hard nosed method for pursuing potentially transformative comparative studies. It is certainly within the realm of possibility that such an inclusivist comparatively oriented potentially transformative theology of religious could revitalize contemporary theological research and reflection not only in Christianity but in other religious traditions as well.

For those who pursue the comparative philosophy of religions in a non theological mode Clooney’s work is no less important. At an empirical or descriptive level his interpretation of his Advaita and Christian texts will foster among such philosophers a new kind of sensitivity to the theological significance of the theological data that they study. At a more theoretical or normative level Clooney’s notion of comparing texts and traditions by means of a back and forth process of creatively ordered reading deserves serious consideration. The highly innovative and creative strategies that he employs in a theological mode are in terms of their basic structure equally relevant for comparativists who identify themselves with secular philosophical traditions.

| Foreword | xiii | |

| Acknowledgements | xvii | |

| Advaita Vedanta | ||

| I | The Elements of the Experiment | 1 |

| II | Comparative Theology | 4 |

| 1. Calling Comparison Theological | ||

| 2. Calling Theology Comparative | ||

| 3. Comparative theology in relation to other Disciplines | ||

| III | Comparative theology as Practical Knowledge | 9 |

| IV | Advaita, text and Commentary | 14 |

| 1. A Brief Overview of the Advaita as a commentarial Tradition | ||

| 2. Advaita as Text: The flourishing of a commentarial tradition | ||

| 3. Advaita as Uttara Mimamsa the purva Mimamsa Paradigm | ||

| V | Practical Implications | 30 |

| 1. Retrieving the Advaita Text | ||

| 2. From the Study of Sankara to the study of the text | ||

| 3. From truth Outside the text to truth after the text | ||

| 4. From Reader as observer to reader as participant | ||

| | ||

| I | The Texture of the Advaita Text | 37 |

| II | The Rough texture of the Upanisads | 38 |

| The Organization of Upanisadic Knowledge in the UMS | 44 | |

| 1. Satra | ||

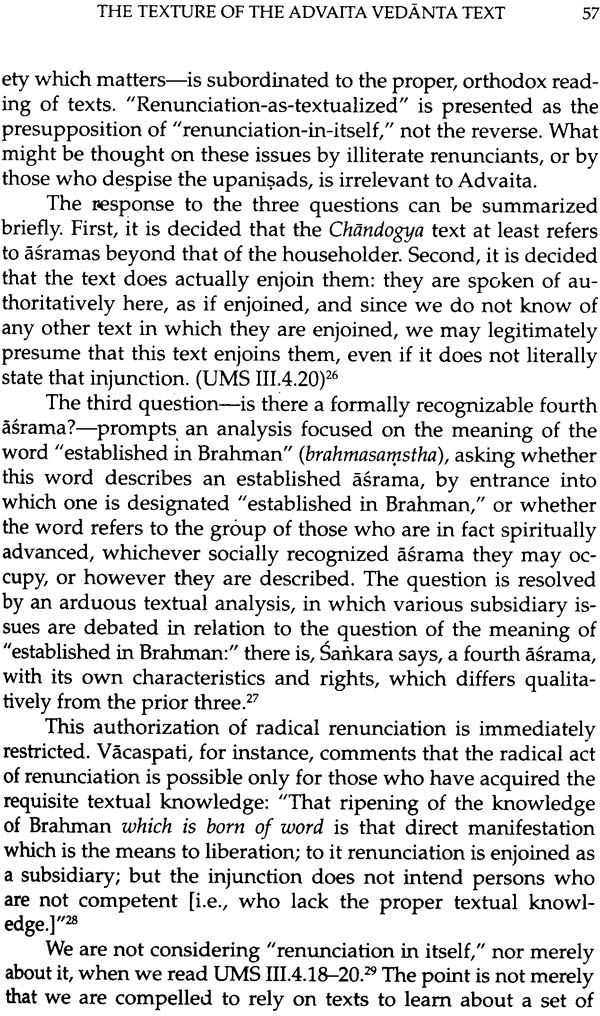

| Abhikarana a. Badarayana’s Statement of the problem regarding Taittiriya 2.1-6a b. Sankara’s two interpretations of taittiriya 2.1-6a c. The Later commentarial contribution to the interpretation of Taittiriya 2.1-6a d. Is there a world outside the text? The case of world renunciation (UMS III.4.18-20) | ||

| 3. Weaving the text together sangati and pada a. sangati the connections within a Pada b. Textured Reasoning (Nyaya) c. Two Strategies of coherent practice i. coordination (Upasamhara) in UMS III.3 ii. Harmonization (samanvaya) In UMS 1.1 | ||

| 4. Adhyaya and the organization of the whole | ||

| IV | The Contextualization of meaning through Engaged reading | 74 |

| | ||

| I | The Problem of Truth in the text | 77 |

| II | Strategies of textual Truth | 79 |

| 1. Denying to Brahman its qualities (nirgunatva) | ||

| 2. Paradoxes in the text (Mahavakyas) | ||

| III | Truth after the text: The True meaning of the Upanisads and the world of Advaita | 88 |

| 1. UMS III.3.11-13 can we assume that Brahman is always bliss? | ||

| 2. UMS I.1.5-11: The Upanisads do have a right meaning | ||

| 3. UMS I.1.2 Inference within the margins of the Upanisads | ||

| 4. UMS IV.3.14 and the Systematization of Advaita | ||

| IV | Defending Brahman the Fragmentation of the other in the text | 102 |

| 1. UMS II 14-11 the relative reasonableness of the Advaita Position | ||

| 2. Arguing the Advaita position UMS II.2.1-10 a. The Structure of UMS II.2 b. The refutation of Samkhya in UMS II.2.1-10 and the Scriptural reasoning of Advaita | ||

| V | Truth Text and Reader | 113 |

| VI | A concluding Note n Advaita and Intertextual truth | 115 |

| | ||

| I | The Tension Between the text and its truth | 119 |

| II | Timeless, Truth Timely Reading: The Truth in reading | 121 |

| 1. The Simplicity and temporal complexity of Liberative knowledge | 113 | |

| 1. The Simplicity and temporal complexity of Liberative knowledge | ||

| 2. Two Analogies: Music and Yoga | ||

| III | Becoming a reader | 129 |

| 1. The Desire to know Brahman and the desire to read | ||

| 2. Authorizing the reader the prerequisites of Knowledge | ||

| IV | The Constraints on Liberation and the cessation of Reading in UMS III.4: Description as prescription | 141 |

| 1. Expectations about the person who will renounce | ||

| 2. The Ritual Background to Renunciation | ||

| 3. Prescribing Renunciation | ||

| V | Advaita Elitism and the Possibility of the Uanuthorized Reader: Finding a Loophole | 149 |

| The text, The Truth, and the theologian | ||

| I | The Practice of Comparative Theology | 153 |

| II | The composition of the text for comparative Theolgoy: Reading the Summa Theologiae and the Uttara Mimamsa Sutras together | 156 |

| 1. Rereading Summa Theologiae I.13.4 after UMS III 3.11-13 | ||

| a. Setting the comparison | ||

| b. Finding Similarities | ||

| c. Finding Differences | ||

| d. Some Strategies for the practice of reading Amalananda and Aquinas together | ||

| i. Coordination (upasamhara) Rules for using texts together | ||

| ii. Superimposition (adhyasa) the Superimposition of One text on another | ||

| iii. The Comparative conversation | ||

| iv. The comparative tension Metaphor, epiphor and Diaphor | ||

| v. Collage, Visualizing the margins of comparison | ||

| 2. Are three Incomparable texts? The Example of ST III.46.3 | ||

| III | The Truth of Comparative theology | 187 |

| 1. The patient Deferral of Issues of truth | ||

| 2. Truth and the conflict of truths in light of the textuality of doctrine | ||

| 3. The truth of the theology of religions | ||

| 4. The Truth about god | ||

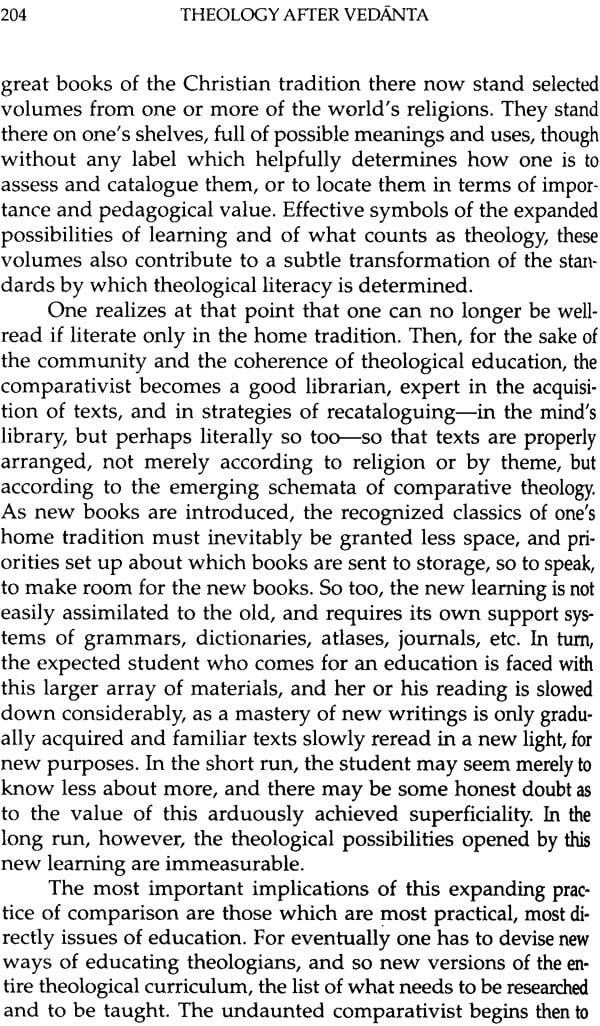

| IV. | The education of the Comparative Theologian | 198 |

| 1. Texts as teachers | ||

| 2. The Education of the comparartivist: Competence Motivation and Limits | ||

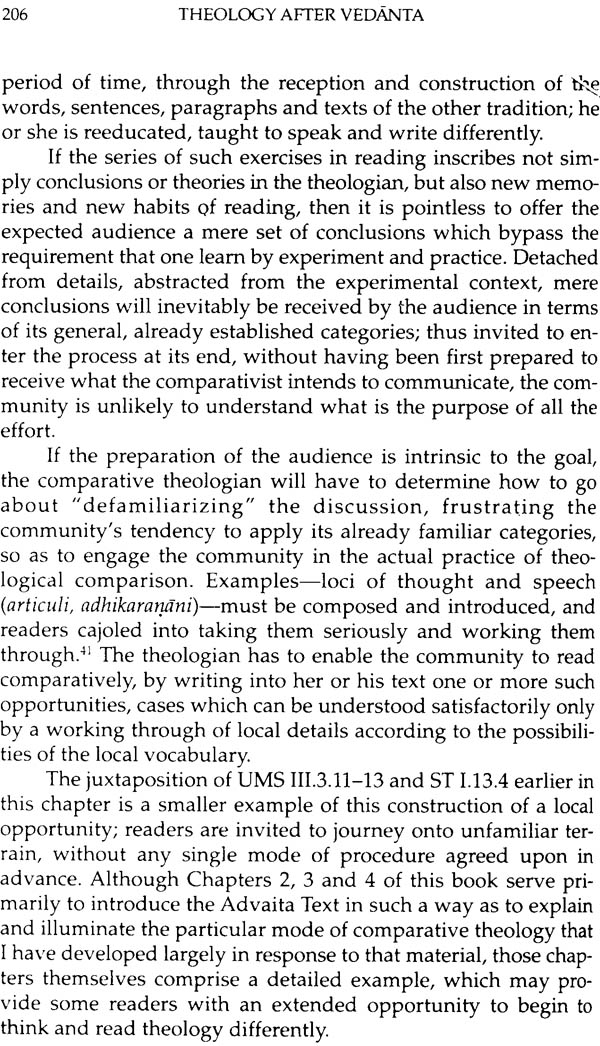

| 3. The Comparativist as educator | ||

| V | Finishing the Experiment | |

| Notes | 209 | |

| Selected Bibliography | 249 | |

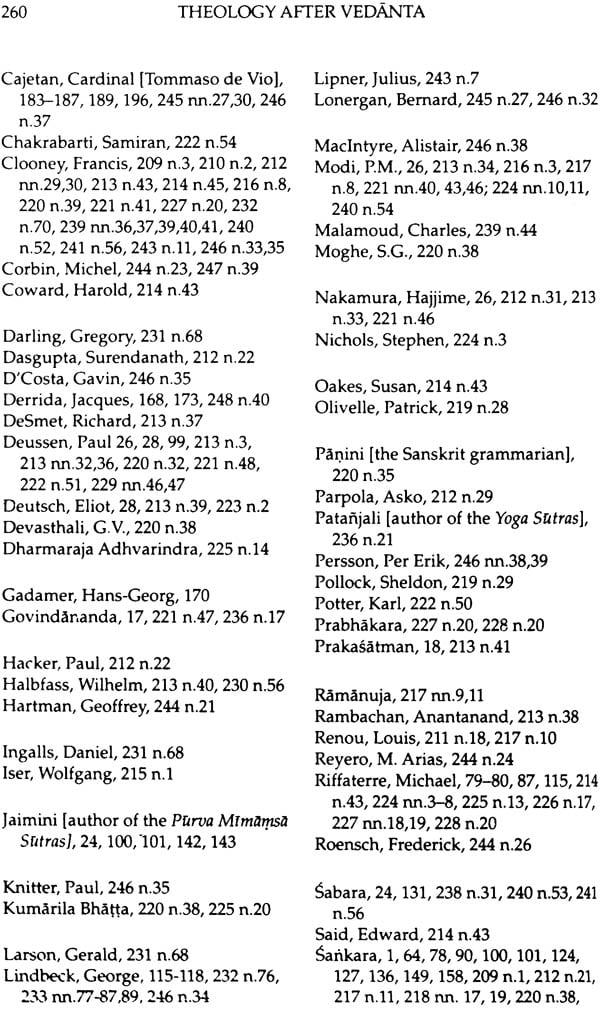

| Index | 257 |