Yoga Education for Children (Volume One)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAD220 |

| Author: | Swami Satyananda Saraswati |

| Publisher: | Yoga Publications Trust |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2009 |

| ISBN: | 97881885787336 |

| Pages: | 412 (With B/W Illustrations ) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 6.0 inch |

| Weight | 510 gm |

Book Description

Yoga Education for Children, Volume One looks at the teaching of yoga to children of all age groups. The first section addresses the topic of yoga and education. Articles and advice from international teachers in the field of yogic education explore the specific needs of children and how yoga can help in their daily life. Topics include: youth problems, integrating yoga into the classroom and improved methods of education. The second section discusses the benefits of yoga therapy in relation to specific groups: the emotionally disturbed, the disabled and juvenile diabetics. The third section on practical yoga provides detailed instructions for asana, prrnayama, concentration techniques and yoga games for children of all ages.

This book is an ideal reference manual for yoga teachers and parents.

Swami Satyananda was born at Almora, Uttar Pradesh, in 1923. In 1943 he met Swami Sivananda in Rishikesh, where he lived as a sannyasin for the next 12 years.

Swami Satyananda founded the International Yoga Fellowship in 1956 and the Bihar School of Yoga in 1963. Over the next 20 years he toured internationally and authored over 80 books.

In 1984 he founded Sivananda Math, a charitable institution for aiding rural development, and the Yoga Research Foundation.

In 1988 he adopted kshetra sannyasa and settled in Rikhia, Jharkhand, where he now lives as a paramahamsa sannyasin.

The present book is intended as a guideline for teachers of yoga to children. It is based on the experience of the various authors who have taught yoga to children in widely differing environments for a considerable number of years. The book indicates some of the requirements of children of different age groups, abilities and disabilities, as well as some of the constraints imposed by the teaching environments. Furthermore, the book presents some of the ways teachers have adapted the general yoga practices to suit their own specific requirements and constraints.

The techniques for practice given in the last section of the book may be used as a basis for one who is new to teaching yoga to children. Both novice and experienced teachers alike can adapt these and other yogic techniques to their particular needs. As this book is a compilation of work from different authors and intended to be a reference and guideline, some information may be repeated.

What is yoga?

Yoga is the art and science of living, and is concerned with the evolution of mind and body. Therefore, yoga incorporates a system of disciplines for furthering an integrated development of all aspects of the individual. When we start the disciplines of yoga we usually begin with the outermost aspect of the physical personality, the physical body. Through the practice of the physical postures, or asanas, the spinal column as well as the muscles and joints are maintained in a healthy and supple state. Subtle massage takes place at the location of different glands, balancing many physiological abnormalities such as hyperthyroid or hypothyroid problems, faulty insulin secretions, and other hormonal imbalances.

Pranayama, or breathing techniques, are important not only for supplying fresh oxygen and strengthening the lungs but because they have a direct effect on the brain and emotions. The emotional stability gained through pranayama frees mental and creative energies in a constructive way, and the child exhibits more self-confidence, self-awareness and self-control.

Relaxation, by withdrawing the awareness from the external environment, or pratyahara, reduces the stress of daily living experiences. Techniques of pratyahara such as yoga nidra affect all aspects of the individual, because physical and mental relaxation through withdrawal of the empirical awareness, and concentration, the focusing of attention, or dharana, are important elements of that technique.

Sustained concentration, or dhyana, is important for stilling the turbulent mind and channeling focused mental energy creatively. Equanimity in daily life can be experienced and later samadhi, the ultimate aim of all yoga practices, is brought about through constant repetition of yogic disciplines. The practice of yoga creates a balance in the total personality. In this book, we will look at the physical, emotional, mental and creative aspects of the personality.

Physical aspect

In this book we will be focusing largely upon the physical aspect, therefore a basic understanding of the major systems is needed.

Supportive systems: the skeletal structure, the musculature, and the linkages between them. The growing child should be encouraged to maintain erect posture without tension and strain. Flexibility, agility and correct posture are very important benefits for young bodies.

Control systems: for example, the nervous system and the endocrine system. The pineal is a tiny gland, located in the medulla oblongata of the brain. In yoga, it is closely linked with ajna chakra, the seat of wisdom and intuition. When the child is about eight years of age, the pineal begins to degenerate. This decay corresponds to the beginning of sexual maturation, precipitated by the release of hormones from the pituitary gland.

Many children do not cope well during this transitional period, when sexual awareness is developing. The high levels of these disturbing hormones in their blood cause an imbalance between their mental and vital fields. ‘Vital’ means prana, the bioenergy, and ‘mental’ means mind. The pranic and mental fields are unable to coordinate with each other and the glands such as the thyroid and adrenals do not work in absolute coordination with each other. Therefore, disruptive behavior is often evinced at this age, such as anger, resentment or violence, much of which can be directly or indirectly attributed to hormonal imbalance.

Why burden a child with sexual responsibility at such a tender age? If we can find a way to delay the decay of the pineal gland, to maintain a balance between the sympathetic (pingala) and the parasympathetic (ida) nervous systems, then the child can continue to experience childhood without the stress of inappropriate impulses.

Metabolic systems: for example, the digestive system and the respiratory system. Since the physiological development of the lungs continues to take place up to the age of eight, it is important that children are encouraged to practice many forms of breathing techniques. Nadi shodhana, alternate nostril breathing, to balance the two hemispheres of the brain, or yogic pranayama, abdominal breathing, are two important examples for achieving efficiency in respiration with little energy drain. Children who swim find breathing exercises help them to swim longer under water. They learn how to utilize their full lung capacity.

Emotional/behavioural aspect

This aspect includes hyperactive behavior, the phenomenon of relaxation and the culture of emotions. In yogic terminology, emotional disturbance is the result of an imbalance of manas shakti (the mental component) and prana shakti (the vital component). Where there is excess mental energy and a lack of prana, the child suffers withdrawal, depression, anxiety or lethargy. He lacks dynamism and cannot transform his mental energy into creative action. Conversely, if the child has excess prana and not enough manas, then he will become very destructive and disruptive. A vast amount of energy with no control spells disaster. It is comparable to a fast moving vehicle without brakes. Such hyperactive children are difficult to live with, and learning is almost impossible for them in this state.

Yoga automatically brings sobriety. Character and sobriety are expressions of inner purity, which cannot be infused solely by speeches. The practices must be performed.

Mental aspect

This includes the ability to concentrate, remember, reason, involving the conscious, subconscious and unconscious mind, and systematic stimulation of both brain hemispheres.

The new look in education had its preview back in May 1978 when the California State University held a conference for educators, educational consultants, counsellors, school and clinical psychologists, teachers and administrators. Workshops were devoted to metaphoric thought, biofeedback, T’ai Chi Chuan, meditation, guided imagery, dreams, psychotherapy, and psychic development in children. The term ‘transpersonal psychology’ was used to cover a broad range of positive inner experience and scientific validation. Teachers need to somehow enlarge their responsibilities to deal with the metaphorical and metaphysical, the aesthetic and dramatic, the spiritual and inspirational. They have dwelt too long on the safe ground of lectures, textbooks, tests and grades.

When we have children we want them to grow, therefore, if we are educators and yogis, we should keep in mind the goal of all these parental and educational cares. Where are we going? That idea is lacking nowadays in normal educational systems. There are techniques but there is no aim. We do not know what a human being can become. We think he or she amounts to being a professional, that he or she is going to be an acrobat or a teacher or a doctor or a carpenter or a good for nothing, but we do not perceive a higher purpose apart from that.

Creative aspect

This aspect includes imagination, visualization, vocalization and cultivation of one’s own personality (as in the use of a resolve in yoga nidra). Children who begin asanas at a very young age can often be observed experimenting how to move from one posture to another in a type of dance. Children who have practiced inner visualization often say that they look at a word and make an inner picture in order to learn to spell and recognize it while reading.

The system of yoga is designed so as to be applicable to any individual no matter what the age, level of interest, abilities or disabilities might be. Of course the potential for development is much greater if the practice of yoga is introduced as early as practicable and applied to individuals who do not suffer from disabilities.

Suitability of yoga for children

The practices of yoga not only help to keep the young body strong and supple but also incorporate mental activities, disciplines that help to develop attention and concentration, and stimulate the creative abilities that are latent within the child. Imagination in children under six is usually expended on toys and fairy tales, but we can also give them real things to imagine, putting them in a more accurate relationship with their environment, making them capable of dealing with this real world. The young child is more intuitive and less conditioned than an adult and is therefore quite open, forthright, creative and, above all, capable of learning. Yoga physiology suggests this is because the pineal gland has not started to degenerate due to calcification and that yoga practices aid in the delay of this degeneration. As the child grows older and enters school, these same yoga practices augment his learning abilities at school, and the regular discipline helps the growing child to channel and direct his emotional energies in a constructive manner.

Need for physical education

Professor Hans Kraus, former physician to J.F. Kennedy, insists that our inactive and overindulgent way of life is particularly dangerous for children who should be building up strong and supple muscles for their adult years. Physically gifted children or those naturally inclined to sports do not suffer as greatly as those who do not take to sports naturally, but even these children need encouragement to develop correct posture. For example, at the first session of a six week course for playgroup leaders, they were asked whether their own four to six year old children were able to bend forward and touch their toes without bending their knees. They all answered, “Of course, they are always running about.” However, to their amazement, they found their children were unable to do this. So, running, climbing, riding, sliding do not necessarily result in a supple, flexible body. Prof. Kraus points out that some form of physical education is essential for all children. So why should children practice yoga and not some other physical exercises, like gymnastics or games?

Such other forms of physical activity are very good and should be introduced, but they are not suitable for all children. However, even children with physical disabilities can participate in yoga exercises because they are not just fast, energy burning, muscle hardening exercise. They are movements and postures for stretching and toning the muscles, for creating flexibility within the skeletal system, and they additionally affect the development and maintenance of healthy nervous and endocrinal systems.

Benefits for physically disabled children

Children who have suffered from polio and many other crippling disabilities have successfully practiced yoga with great benefit. What is more important, their social development and their well-being benefits from the fact that they are able to participate in a class or session involving also the strongest and heartiest of children. This would be impossible under the conditions of gymnastics and games that presuppose normal health and require physical stamina or fast movements and competitiveness. Yoga is the answer for children who are in some way physically disabled to enjoy physical education without being set apart as different. Mentally disabled children can also benefit from yoga postures, kirtan, pranayama and karma yoga.

Yoga therapy for emotional disabilities

Emotionally disturbed, destructive, aggressive, hyperactive children can benefit from yogic discipline. The hyperactive child is restless, unable to concentrate or finish a job, overtalkative and a poor school performer. His troubles normally start at a very early age and are usually noticed by the mother before the child is two years of age. These children tend to have a history of feeding problems, disturbed sleep and poor general health in the first years of life. Many of these children have been disabled by delayed development of speech and poor coordination. As teenagers they tend to be more impatient, more resistant to discipline than their peers, and more prone to irritability and telling lies. A high proportion engage in fighting, stealing and deviant behavior such as running away from home, going with a ‘bad crowd’ and playing truant; drinking is also not uncommon.

Amphetamines are being used to treat these hyperactive children. They act on the reticular formation, a key area in the brain stem at the top of the spinal cord, controlling consciousness and attention. Under their influence, the hyperactive child becomes quieter, exhibits a longer attention span, greater perseverance with assigned work and performs better at school. Amphetamines have a very similar effect on adults. They stimulate the release of noradrenalin, a neurotransmitter substance, from nerve endings and, therefore, in some way the normal balance of activity between noradrenalin and acetylcholine, another neurotransmitter, is brought about. However, the problem of drug treatment is that the effect of drugs is only temporary. When they wear off the child reverts to his usual behavior. Additionally, drug treatment continued into adolescence leads to the danger of overuse and habituation.

In an article entitled, ‘Charts of the Soul’, in OMNI (1938), J. Hooper reported that F. Farley, an educational psychologist at the University of Wisconsin, suggests that hyperactivity and many learning difficulties are disorders of severe underarousal of the neural system. Other neurophysiologists are tracing the root of many of these related problems to a dopamine-acetylcholine imbalance; both neurotransmitters are necessary in the brain for transmission of impulses from one nerve cell to the other. Pranayama together with asanas works directly on the brain and the endocrinal system and, therefore, on the mind and emotional nature of the child, helping to re-establish emotional harmony and psychomotor normality, that is, normal attention span. We will illustrate the effect of yoga on hyperactive, aggressive children by recounting our experience and point out the need for a more accurate knowledge of the wide ranging effects of yoga practices.

A nine-year-old child was brought by his mother for yoga classes. She reported that he got up in the morning, beat his five year old brother before noisily going off to school where he also showed disruptive, aggressive behavior. The only thing he seemed to enjoy was singing with the Vienna Boys Choir. At the end of the first yoga session he was told if he had enjoyed the class he should come back the following week; but if he did not want to come again he did not have to. He came back, with his mother’s encouragement we are sure.

After a few sessions he was given his own practice, or sadhana, to be done every morning before breakfast. It consisted of surya namaskara, a series of twelve postures, and seven rounds each of simple alternate breathing in the nostrils, and bhramari pranayama, the humming bee breath.

Several months later his mother telephoned to say that if the director of the Vienna Boys Choir called, he should be told that her son was attending yoga classes on Thursday afternoons for the correction of a spinal problem. The class clashed with one of the choir practices on Thursday afternoons. She did not want him to stop either the yoga or the choir because he had become a much happier child at home. He did his yoga every morning then came quietly to breakfast before going to school.

When it was suggested that the director should be told that the boy was doing yoga to help correct an emotional problem, she insisted that he would not understand or accept that as a reason for attending a yoga class. This sadly reflects a common misconception that yoga is only a form of physical education and cannot form a basis of therapy for emotionally disturbed children as well. Yoga helps the child to channel his emotions and stimulates creativity in emotionally disabled children, which is not easily done with other forms of physical education.

Obviously, yoga is a form of complete education that can be used with all children because it develops physical stamina, emotional stability and intellectual and creative talents. It is a unified system for developing the balanced, total personality of the child.

| Introduction | 1 | |

| Yoga and Education | ||

| 1 | The Need for a Yoga-Based Education System | 13 |

| 2 | Yoga and Children's Problems | 22 |

| 3 | Yoga with Pre-School Children | 25 |

| 4 | Yoga Lessons Begin at Age Eight | 31 |

| 5 | Student Unrest and Its Remedy | 34 |

| 6 | Yoga and the Youth Problem | 39 |

| 7 | Better Ways of Education | 45 |

| 8 | Yoga at School | 50 |

| 9 | Yoga and Education | 57 |

| 10 | Questions and Answers | 65 |

| Yoga as Therapy | ||

| 11 | Yoga for Emotional Disturbances | 77 |

| 12 | Yoga for the Disabled | 83 |

| 13 | Yoga Benefits Juvenile Diabets | 87 |

| Practices | ||

| 14 | Yoga Techniques for Pre-School Children | 93 |

| 15 | Yoga Techniques for 7-14 Year-Olds | 101 |

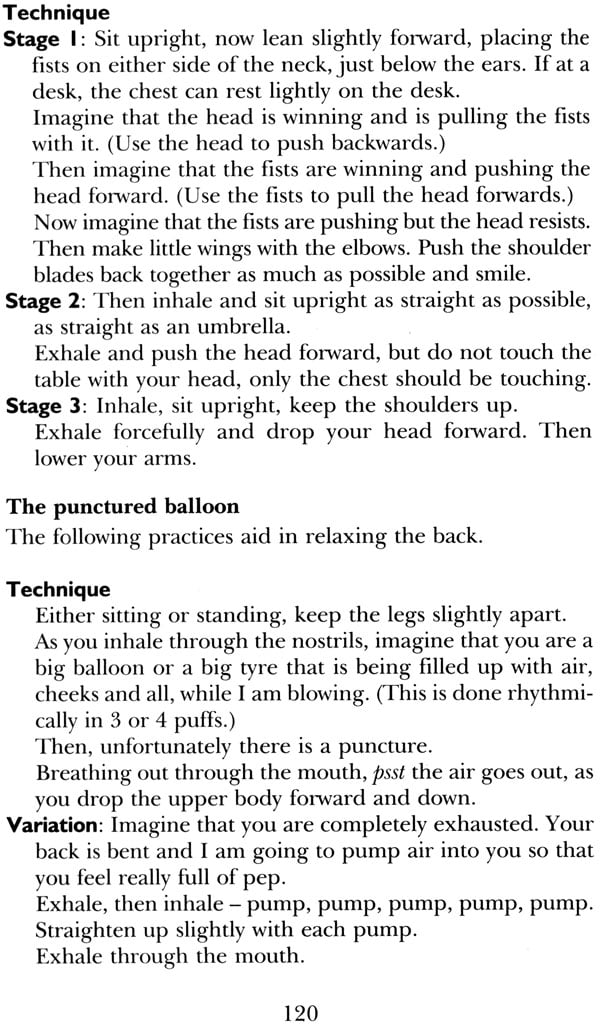

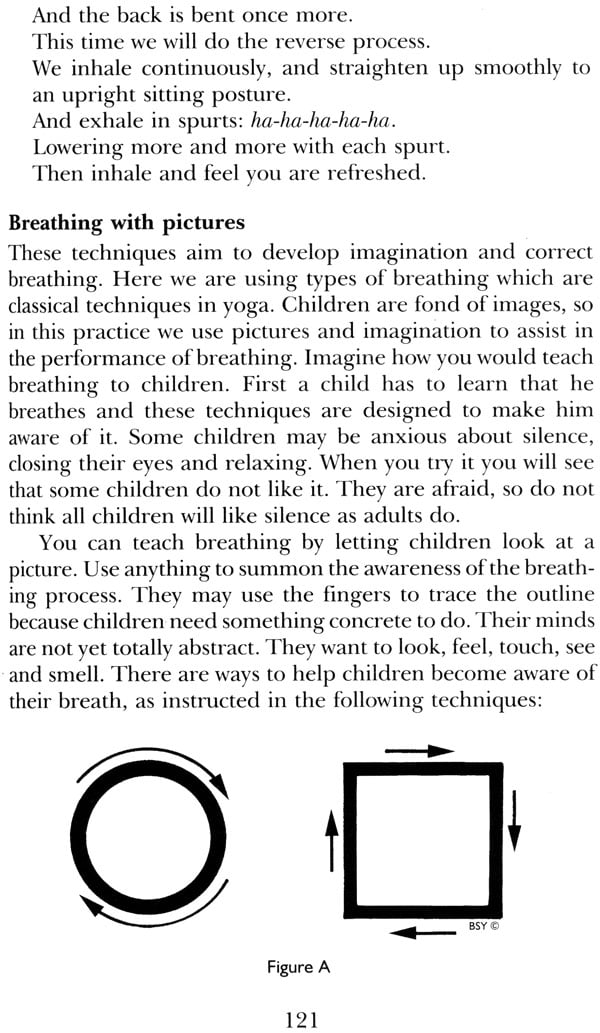

| 16 | Yoga Techniques for the Classroom | 110 |

| 17 | Introduction to Asana | 133 |

| 18 | Pawanmuktasana Series | 139 |

| Pawanmuktasana 1: Anti-Rheumatic Asanas | 141 | |

| Pawanmuktasana 2: Anti-Gastric Asanas | 156 | |

| Pawanmuktasana 3: Energizing Asanas | 165 | |

| 19 | Eye Exercises | 171 |

| 20 | Surya Namaskara: Salutations to the Sun | 176 |

| 21 | Chandra Namaskara: Salutations to the Moon | 182 |

| 22 | Warrior Sequence | 188 |

| 23 | Relaxation Asanas | 193 |

| 24 | Animal Asanas | 196 |

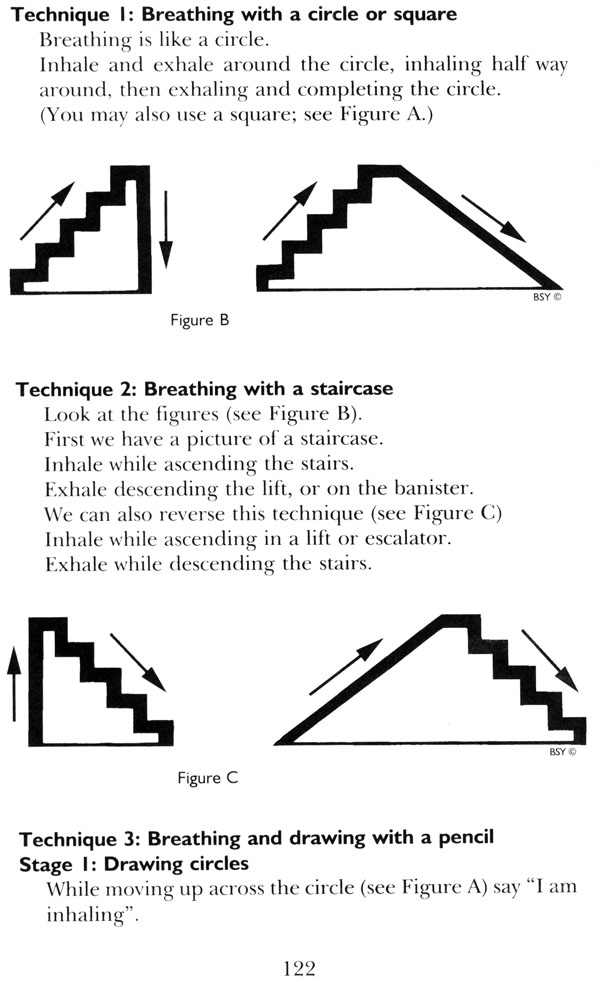

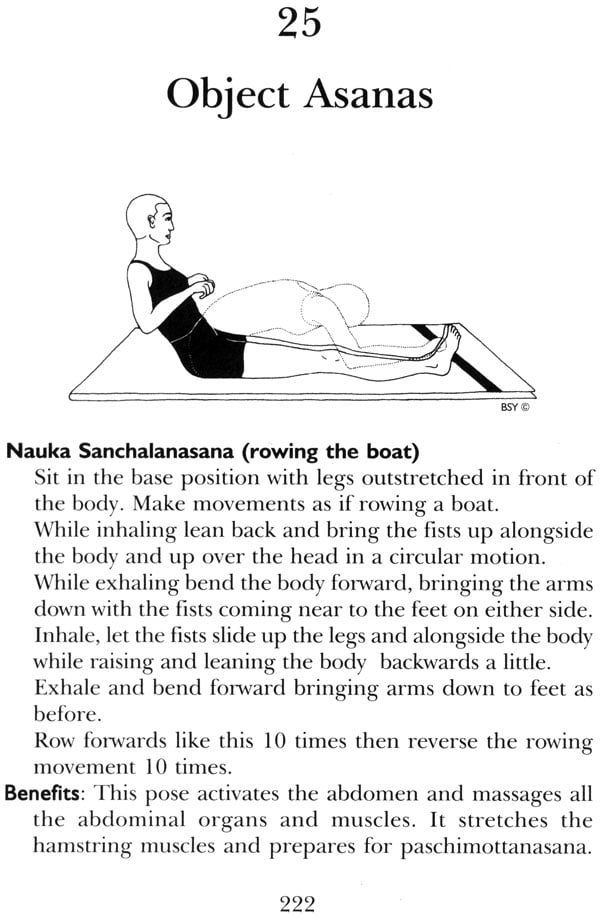

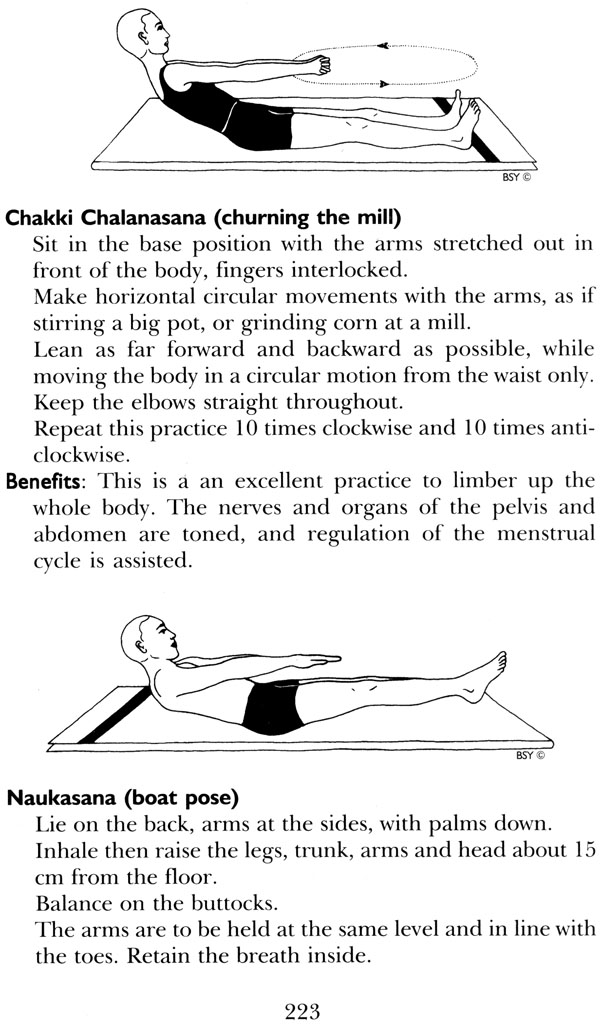

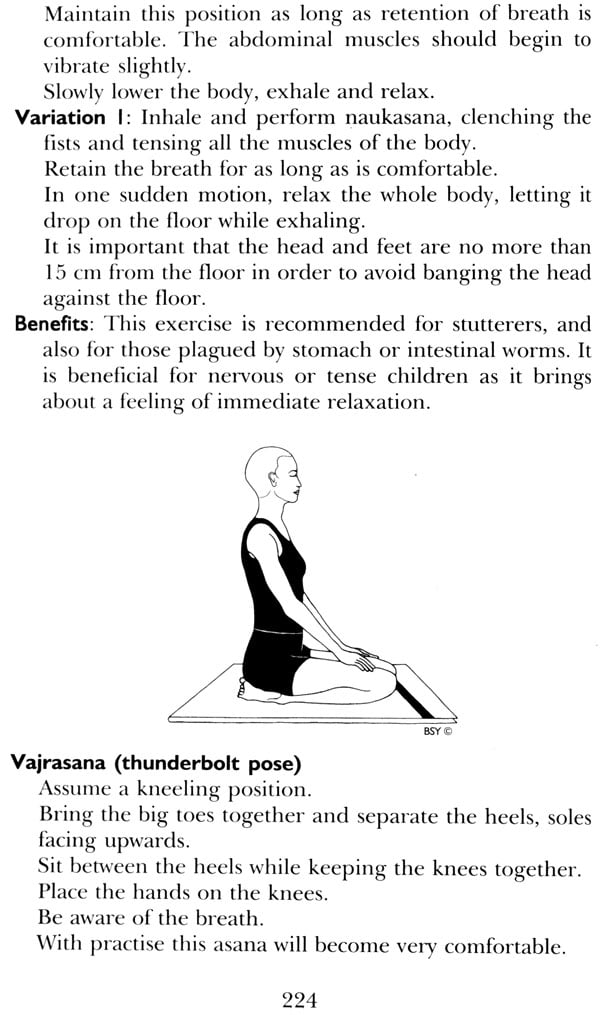

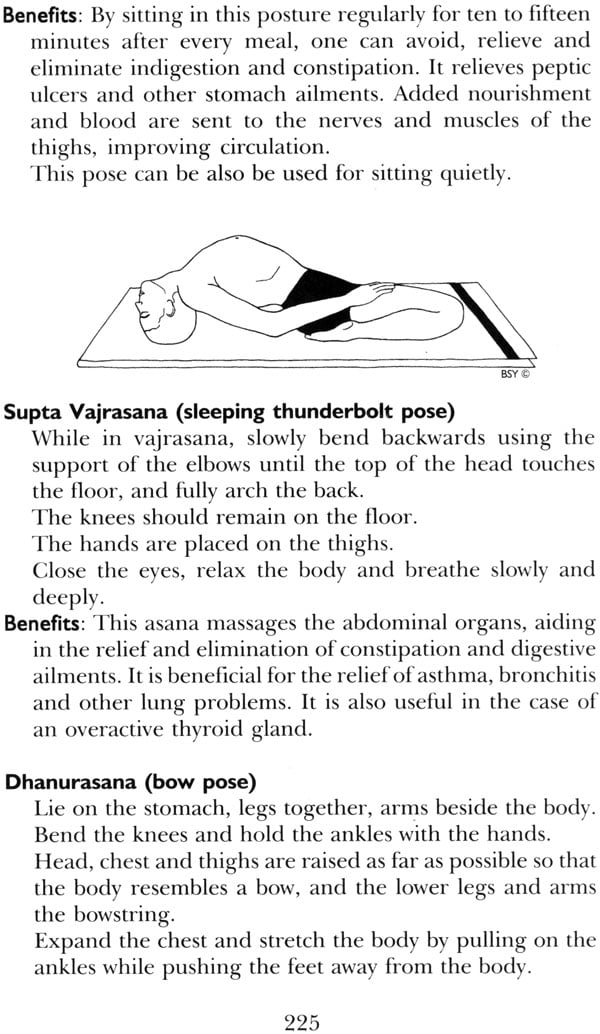

| 25 | Object Asanas | 222 |

| 26 | Characters and Persons | 249 |

| 27 | Alphabet Asanas | 255 |

| 28 | Asanas Done in Pairs | 259 |

| 29 | Pranayama | 264 |

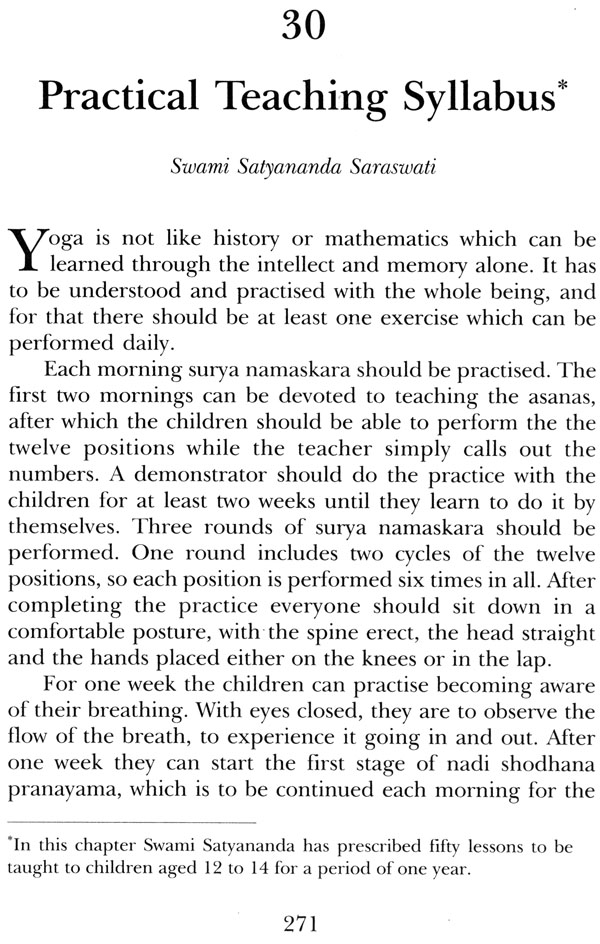

| 30 | Practical Teaching Syllabus | 271 |

| 31 | Light of Existence Explained | 285 |

| Bibliography | 290 | |

| Index of Practices | 293 | |

| General Index | 298 |