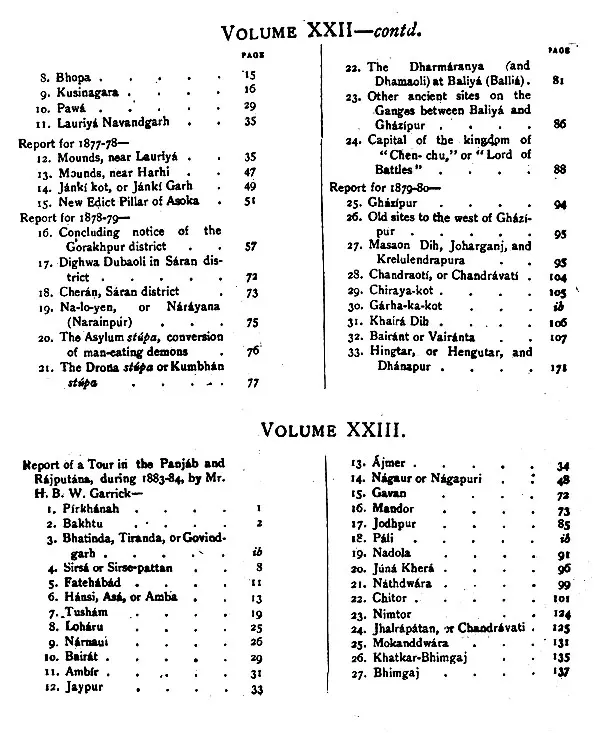

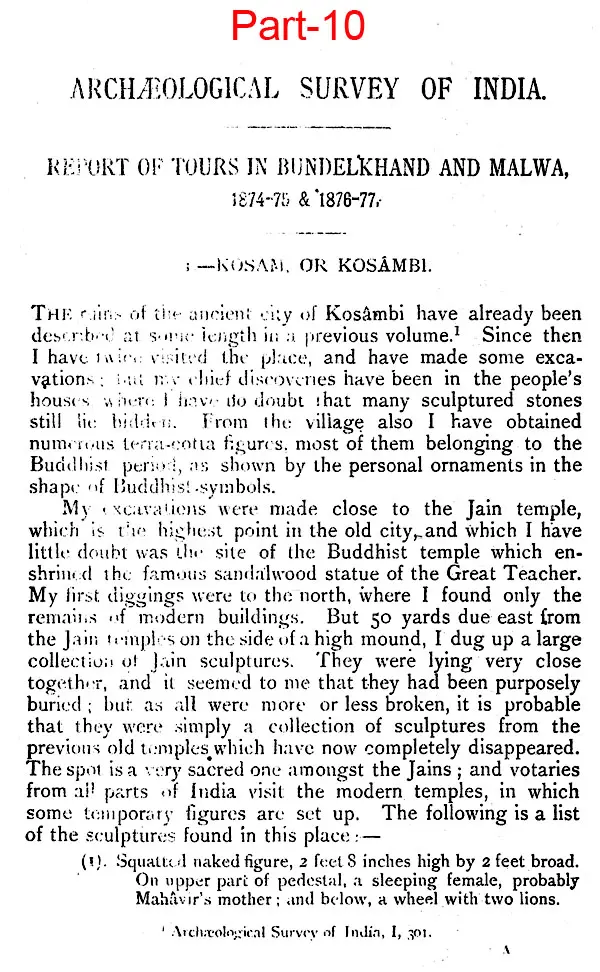

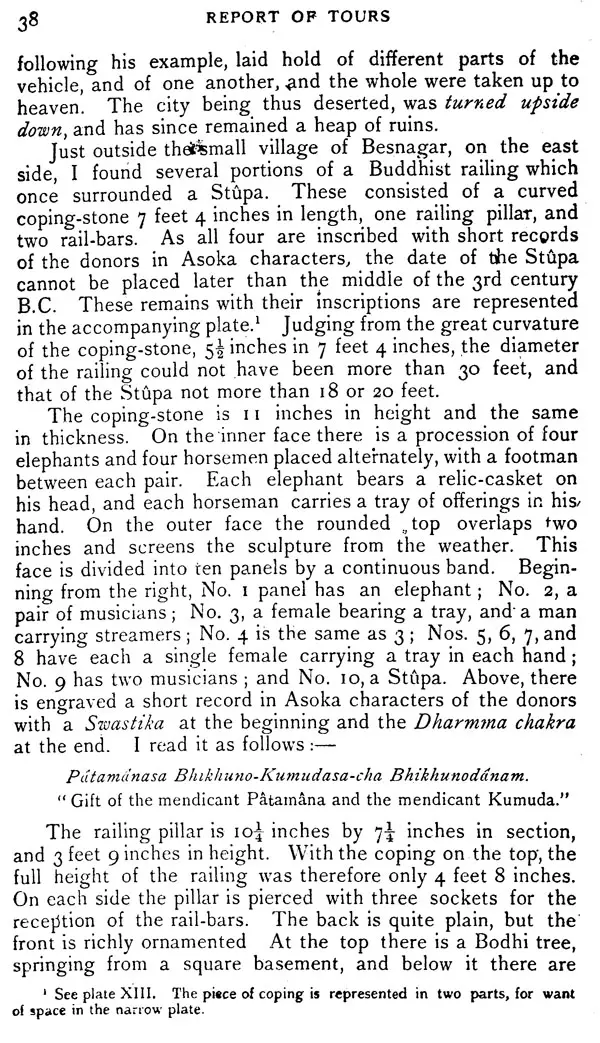

Archaeological Survey of India (Four Reports) Made During the Years (1862-65 to 1873-76) by Alexander Cunningham (Set of 23 Volume & One Index Book)

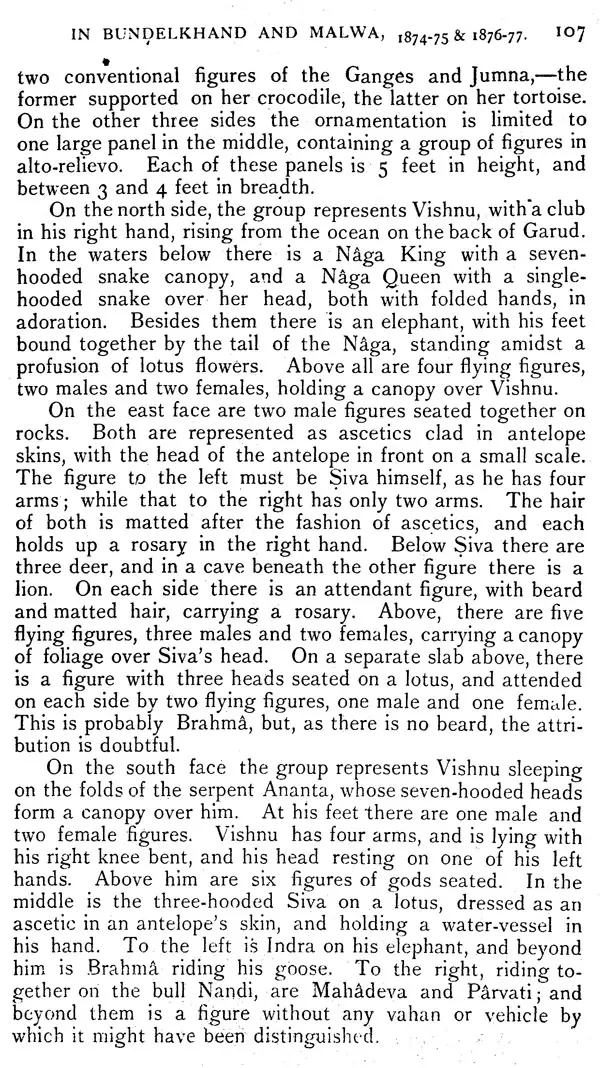

Book Specification

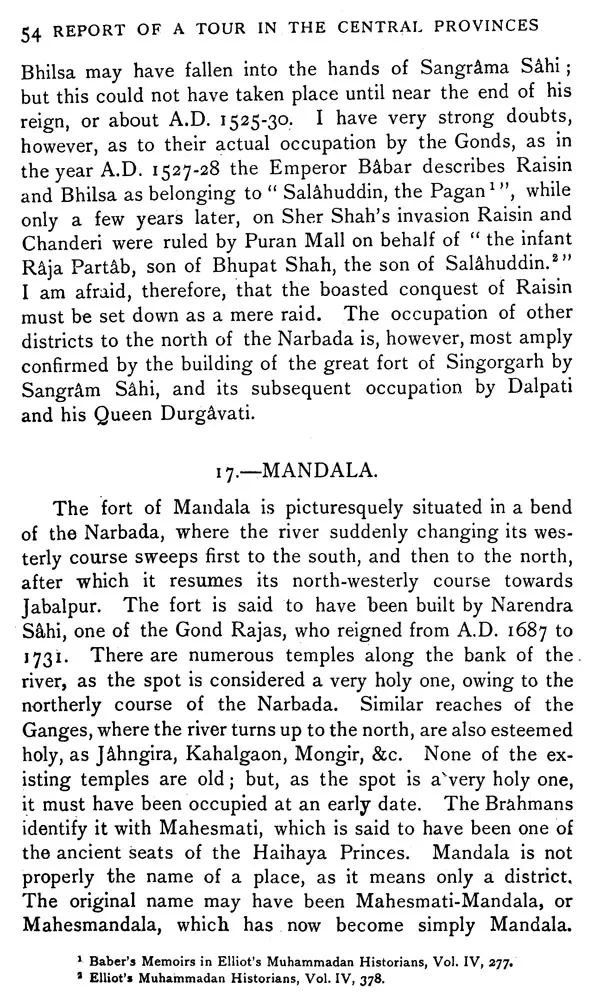

| Item Code: | UAQ850 |

| Author: | Alexander Cunningham |

| Publisher: | Rahul Publishing House |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1994 |

| ISBN: | 8173880212 |

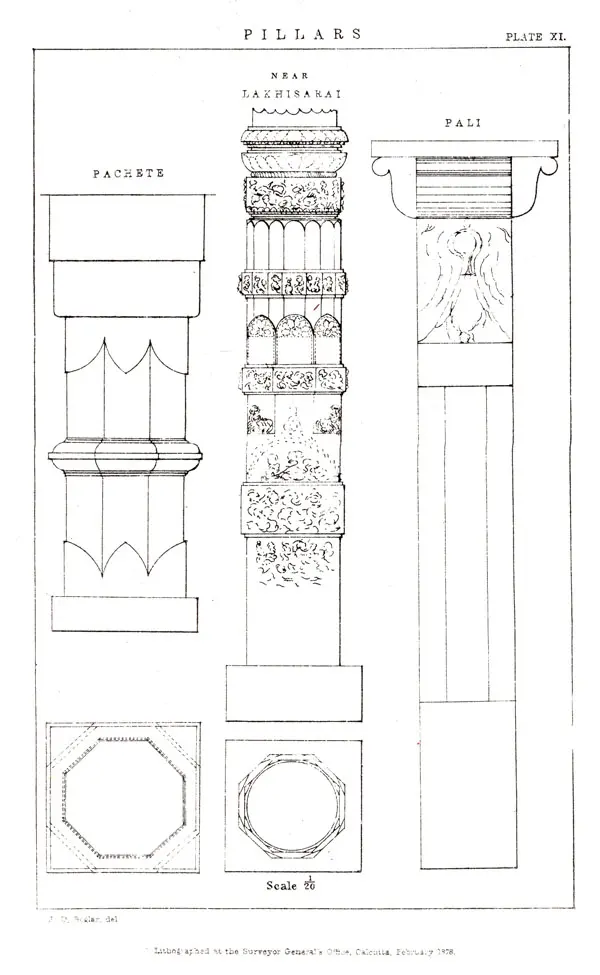

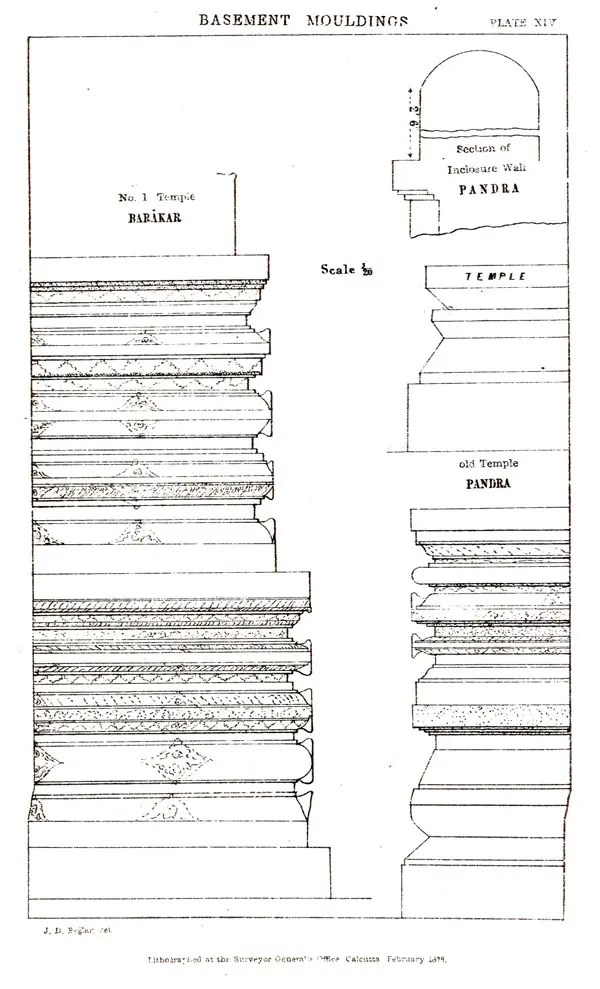

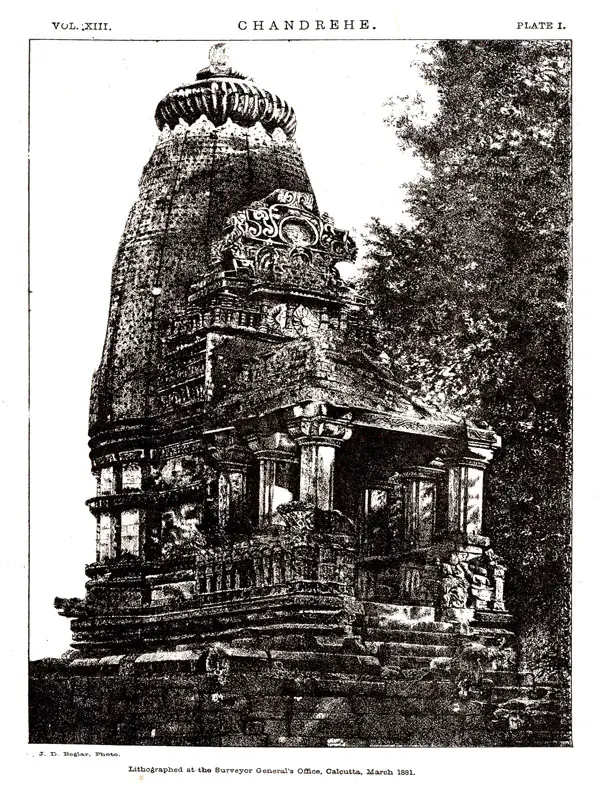

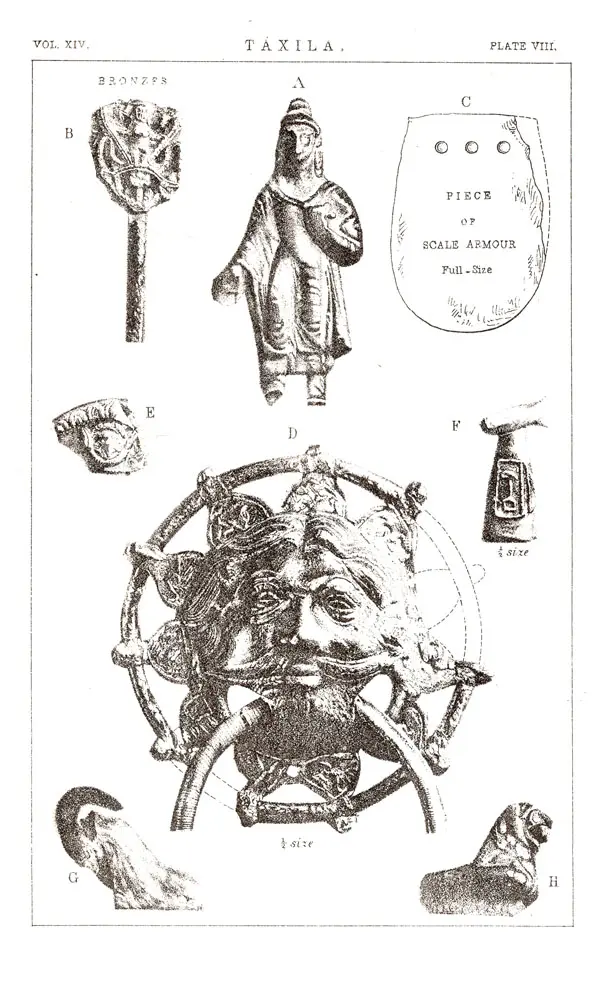

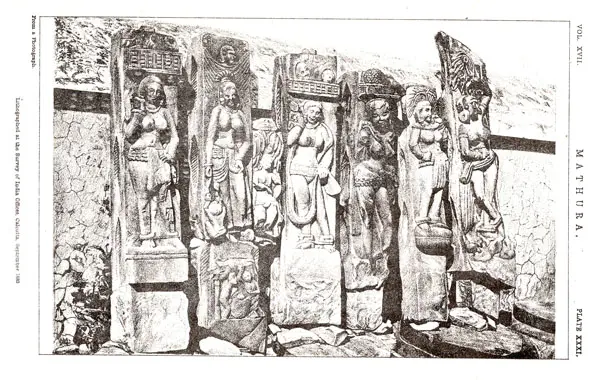

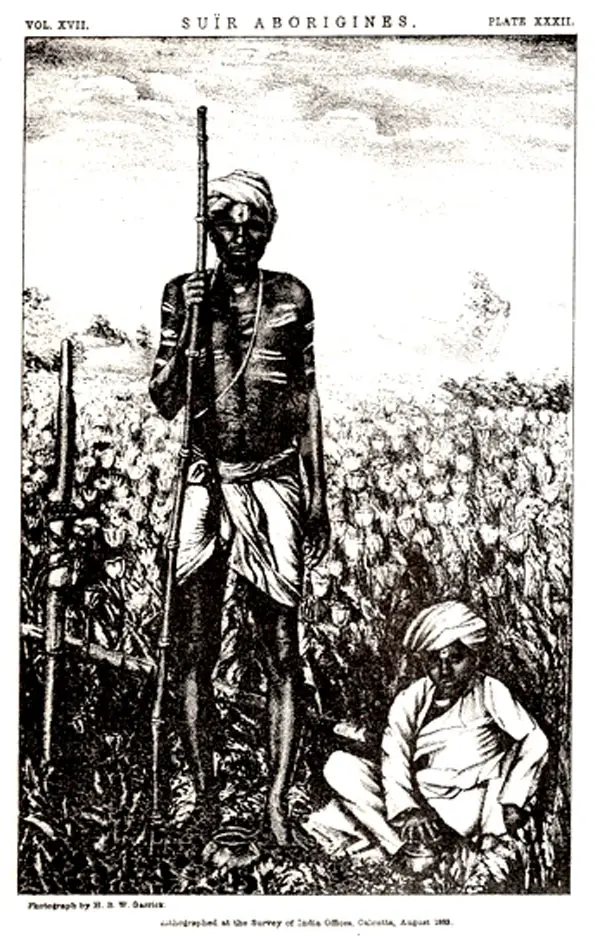

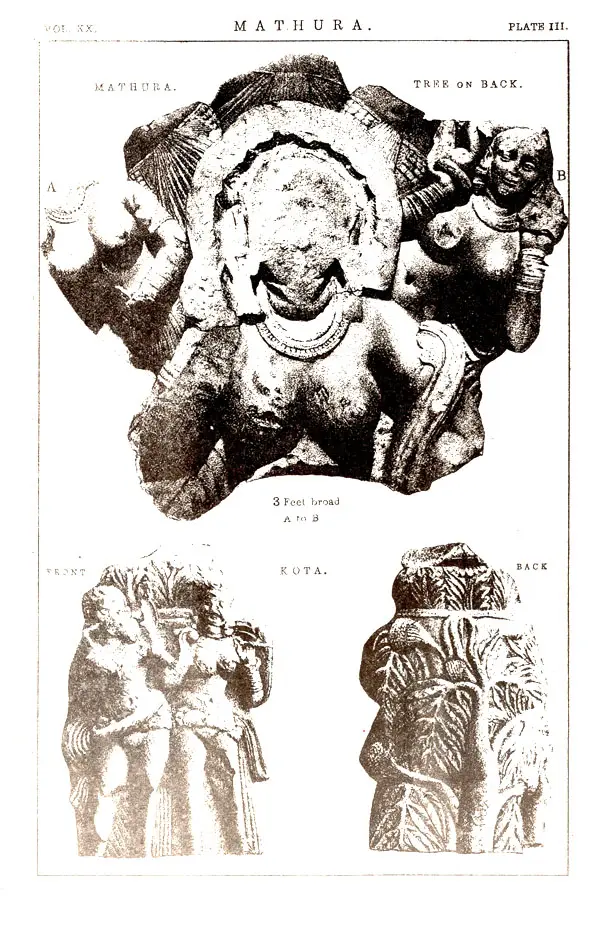

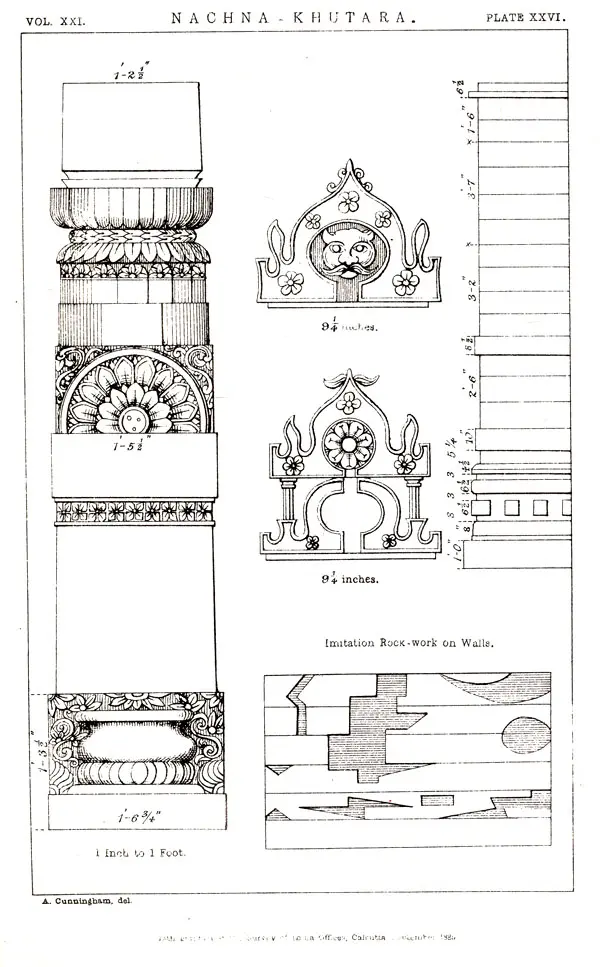

| Pages: | 5703 (Throughout B/w Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 10.95 kg |

Book Description

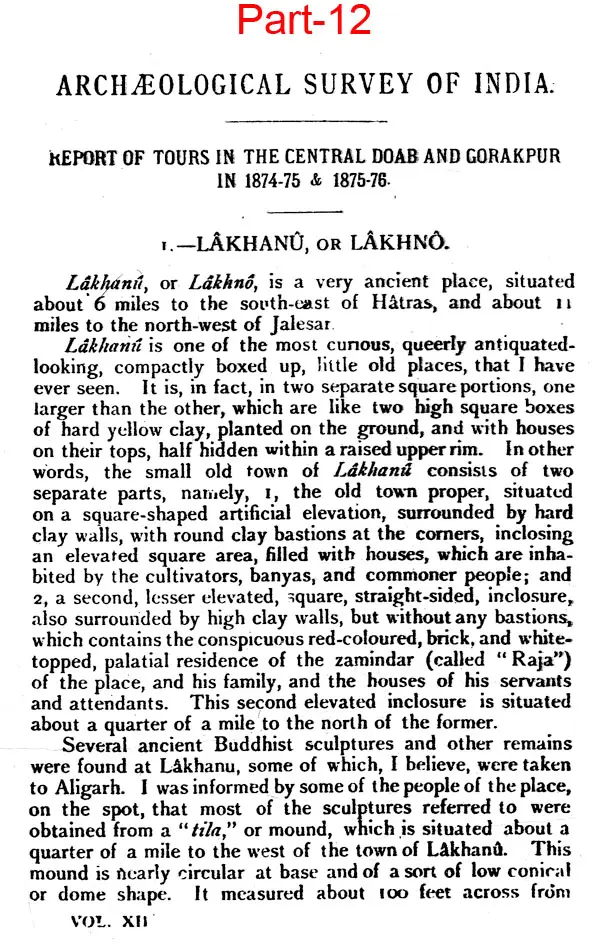

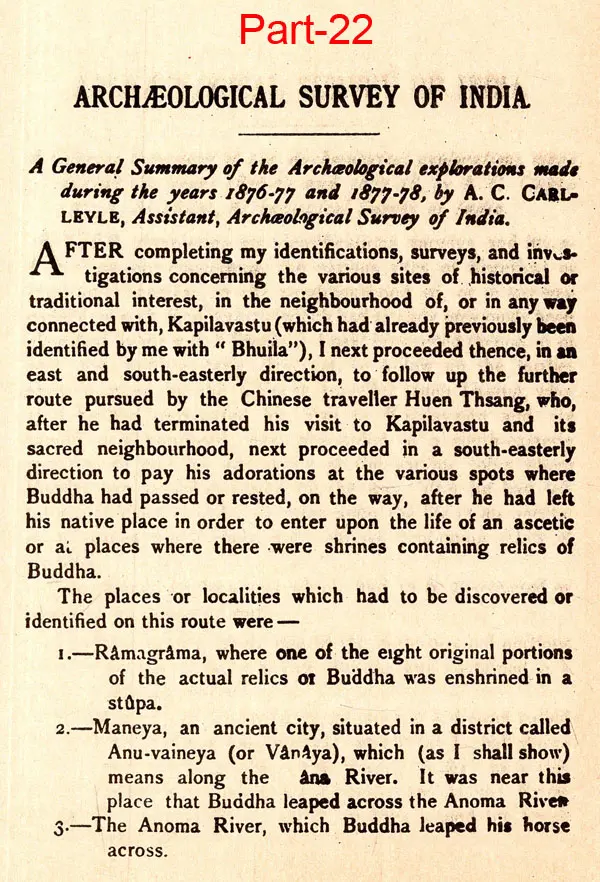

Sir Alexander Cunningham's contribution in Indian Cultural History and Indian Archaeology is great and in fact he may be regarded as the father of Indian Cultural History and Archaeology. He was appointed as Director General of Archaeology in 1862. This year and the appointment of Sir Alexander Cunningham are the beginning points of Systematic research in the field of Indian Archaeology. Under Cunningham the Archaeology research in India was founded and well-established during the period 1862-1884. Cunningham's extensive Archaeology researches in all parts of India, facing many hazards and hindrances like old age, ill-health, the-then technical know-how employed for excavations and survey all were an Odyssey facing many Odds. But Cunningham's personal hardships and he himself are long forgotten and have gone into pages of Cultural History. Now Cunningham is remembered for his Reports of Archaeology Survey of India. His monumental twenty-three Volumes of Reports and one Volume of Index published during the years 1862 1884 is not forgotten. In fact, they are the founding stones of Indian Cultural History and Archaeology. They are the base upon which many generations of Indian historical researches based their researches and future generations will continue to do so.

Since the publication of these. Reports' one century and many years have passed. This time period is long enough to make a work rare and forgotten. So it is good to see Old Cunningham's work in a fresh reprint. His reports are still useful and relevant for Indian Cultural History and historical researches. Bound in attractive and uniform bindings these Reports would be a pride possession.

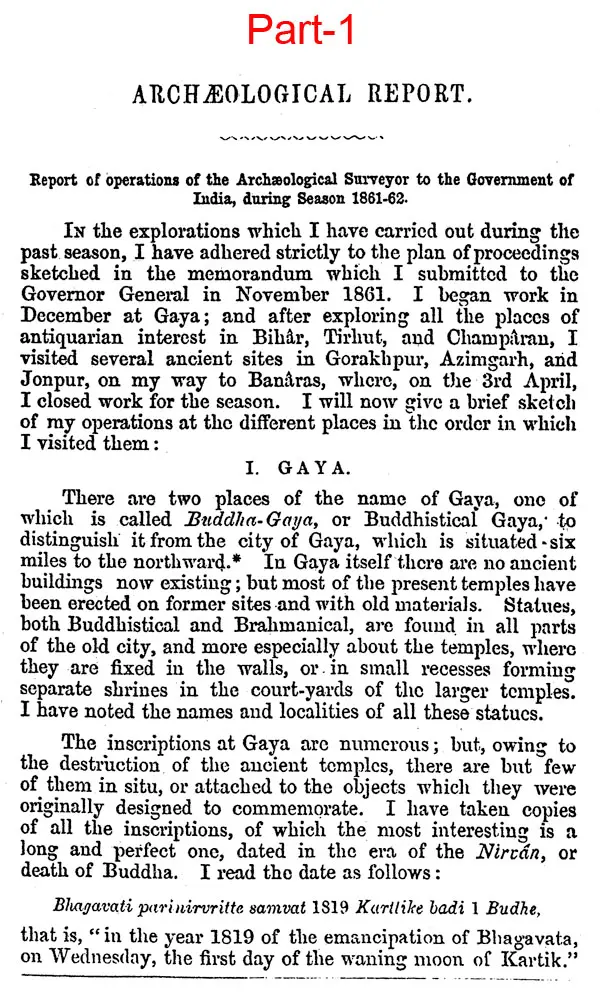

The matter contained in these two volumes is the result of the archaeological survey which I conducted during four consecutive years from 1862 to 1865. The object of this survey cannot be better stated than in the memorandum which I laid before Lord Canning in November 1861, and which led to my immediate appointment as Archeological Surveyor to the Government of India, as notified in the following minute:

Minute by the Right Hon'ble the GOVERNOR GENERAL OF INDIA in Council on the Antiquities of Upper India,-dated 22nd January 1862.

"IN November last, when at Allahabad, I had some com munications with Colonel A. Cunningham, then the Chief Engineer of the North-Western Provinces, regarding an investigation of the archaeological remains of Upper India.

"It is impossible to pass through that part, or indeed, so far as my experience goes any part of the British ter ritories in India without being struck by the neglect with which the greater portion of the architectural remains, and of the traces of by-gone civilization have been treated, though many of these, and some which have had least notice, are full of beauty and interest.

"By neglect I do not mean only the omission to restore them, or even to arrest their decay; for this would be a task which, in many cases, would require an expendi ture of labour and money far greater than any Government of India could reasonably bestow upon: it.

"But so far as the Government is concerned, there has been neglect of a much cheaper duty, that of investigat ing and placing on record, for the instruction of future generations, many particulars that might still be rescued from oblivion, and throw light upon the carly history of England's great dependency; a history which, as time moves on, as the country becomes more easily accessible and traversable, and as Englishmen are led to give more thot ght to India than such as barely suffices to hold it and govern it, will assuredly occupy, more and more, the attention of the intelligent and enquiring classes in European countries.

"It will not be to our credit, as an enlightened rulling power, if we continue to allow such fields of investigation, as the remains of the old Buddhist capital in Belar, the vast ruins of Kanouj, the plains round Delhi, studded with ruins more thickly than even the Campagna of Rome, and many others, to remain without more examination than they have hitherto received. Every thing that has hitherto been done in this way has been done by private persons, imper fectly and without system. It is impossible not to feel that there are European Governments, which, if they had held our rule in India, would not have allowed this to be said.

"It is true that in 1844, on a representation from the Royal Asiatic Society, and in 1847, in accordance with detailed suggestions from Lord Hardinge, the Court of Directors gave a liberal sanction to certain arrangements for examining, delineating, and recording some of the chief antiquities of India. But for one reason or another, mainly perhaps owing to the officer entrusted with the task having other work to do, and owing to his early death, very little seems to have resulted from this endeavour. A few drawings of antiquities, and some remains, were transmitted to the India House, and some 15 or 20 papers were contributed by Major Kittoe and Major Cunningham to the Journals of the Asiatic Society; but, so far as the Government is con cerned, the scheme appears to have been lost sight of within two or three years of its adoption.

"I enclose a memorandum drawn up by Colonel Cunning ham, who has, more than any other officer on this side of India, made the antiquities of the country his study, and who has here sketched the course of proceeding which a more complete and systematic archeological investigation. should, in his opinion, take.

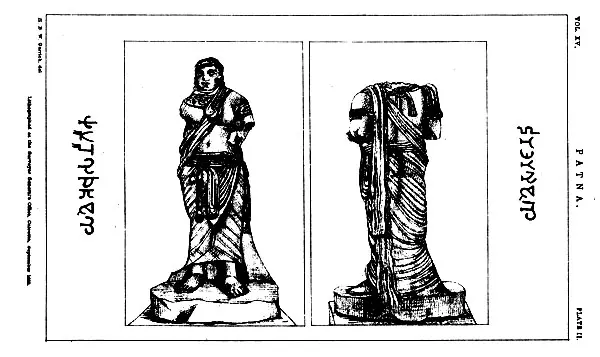

THE study of Indian antiquities received its first im pulse from SIR WILLIAM JONES, who in 1784 founded the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Amongst the first members were Warren Hastings, the ablest of our Indian rulers, and Charles Wilkins, who was the first Englishman to acquire a knowledge of Sanskrit, and who cut with his own hands the first Devanagari and Bengali types. During a residence of little more than ten years, Sir William Jones opened the treasury of Sanskrit literature to the world by the transla tion of Sakuntala and the institutes of Manu. His annual discourses to the Society showed the wide grasp of his mind; and the list of works which he drew up is so comprehensive that the whole of his scheme of translations has not evan yet been completed by the separate labours of many suc cessors. His first work was to establish a systematic and uniform system of orthography for the transcription of Oriental languages, which, with a very few modifications, has since been generally adopted. This was followed by several essays-On Musical Modes-On the Origin of the Game of Chess, which he traced to India-and On the Lunar Year of the Hindus and their Chronology. In the last paper he made the identification of Chandra-Gupta with Sandra kottos, which for many years was the sole firm ground in the quicksands of Indian history. At the same time he suggested that Palibothra, or Pataliputra, the capital of Sandrakottos, must be Patna, as he found that the Son River, which joins the Ganges only a few miles above Patna, was also named Hiranyabáhu, or the "golden-armed," an appellation which at once re-called the Erranoboas of Arrian.

The early death of Jones in 1794, which seemed at first to threaten the prosperity of the newly established Society, was the immediate cause of bringing forward Colebrooke, so that the mantle of the elder was actually caught as it fell by the younger scholar, who, although he had not yet appeared as an author, volunteered to complete the Digest of Hindu Law, which was left unfinished by Jones.

CHARLES WILKINS, indeed, had preceded him in the translation of several inscriptions in the first and second volumes of the Asiatic Researches, but his communications then ceased, and on Jones' death in 1794 the public looked to Davis, Wilford, and Colebrooke for the materials of the next volume.

SAMUEL DAVIS had already written an excellent paper on Hindu astronomy, and a second on the Indian cycle of Jupiter; but he had no leisure for Sanskrit studies, and his communications to the Asiatic Society now ceased altogether.

FRANCIS WILFORD, an officer of engineers, was of Swiss extraction. He was a good Classical and Sanskrit scholar, and his varied and extensive reading was success fully brought into use for the illustration of ancient Indian geography. But his judgment was not equal to his learning and his wild speculations on Egypt and on the Sacred Isles of the West, in the 3rd and 9th volumes of the Asiatic Researches, have dragged him down to a lower posi tion than he is justly entitled to both by his abilities and his attainments. His "Essay on the comparative Geogra phy of India," which was left unfinished at his death, and which was only published in 1851 at my earnest recom mendation, is entirely free from the speculations of his. earlier works, and is a living monument of the better judg ment of his latter days.

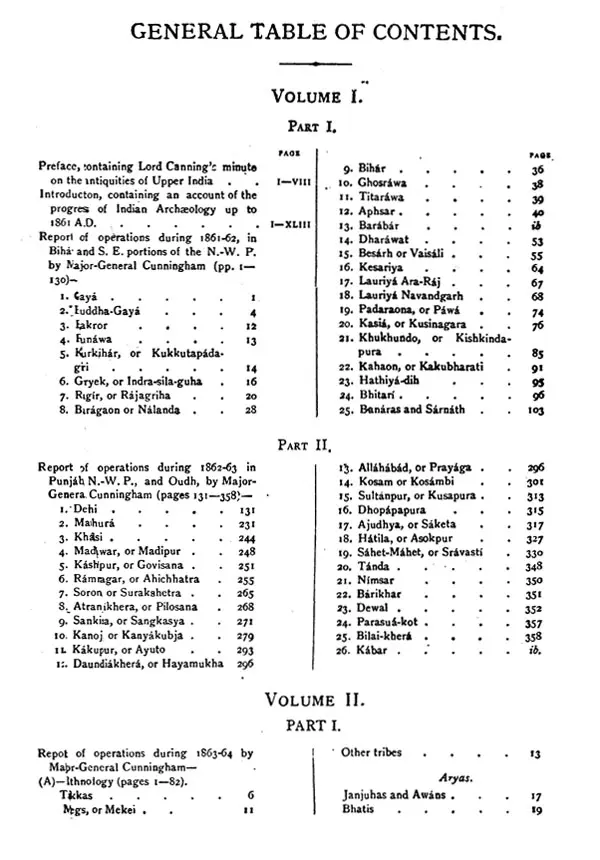

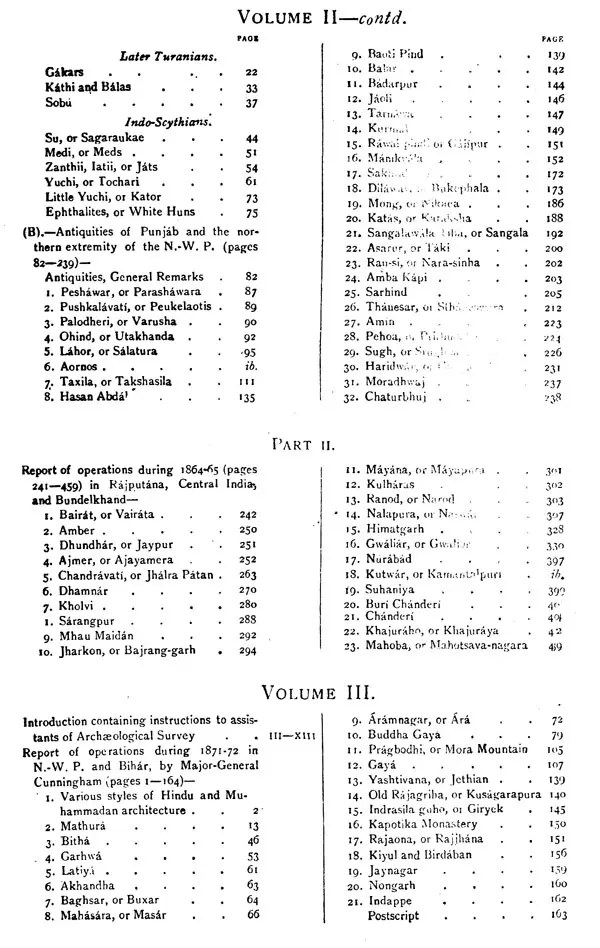

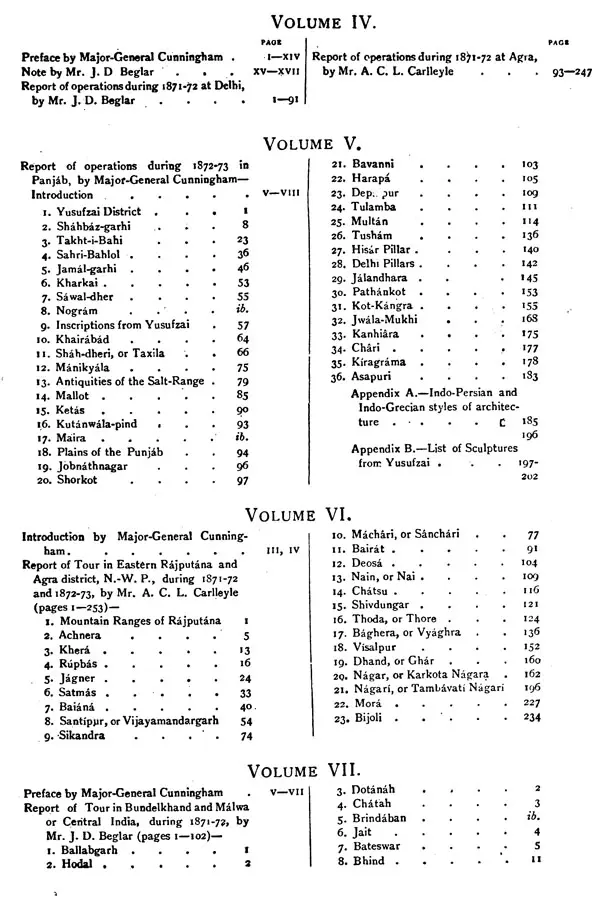

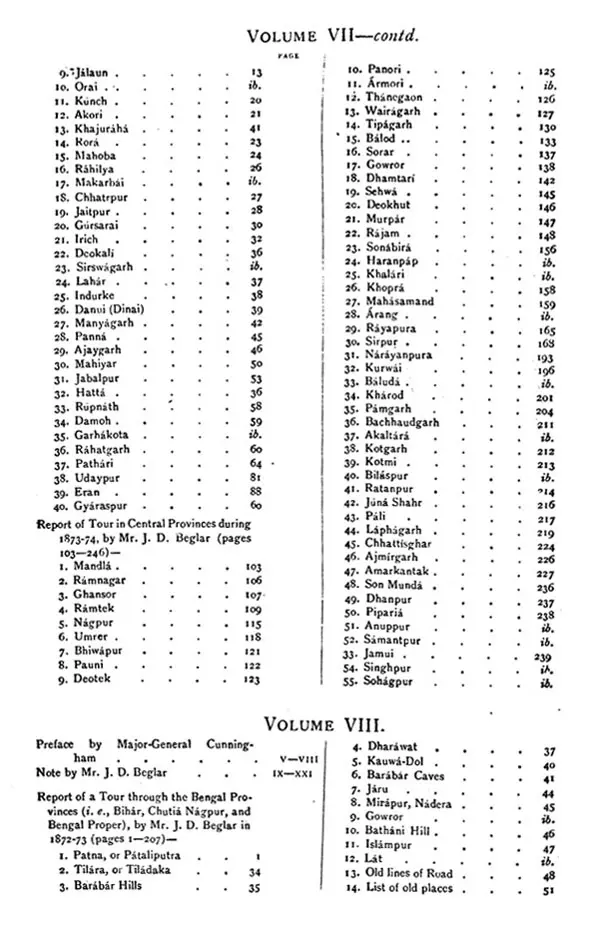

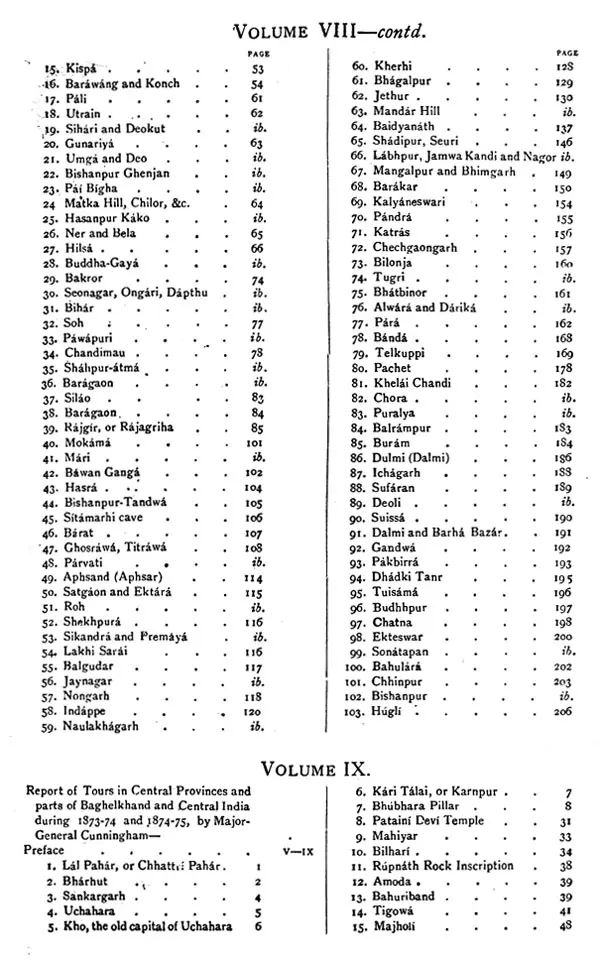

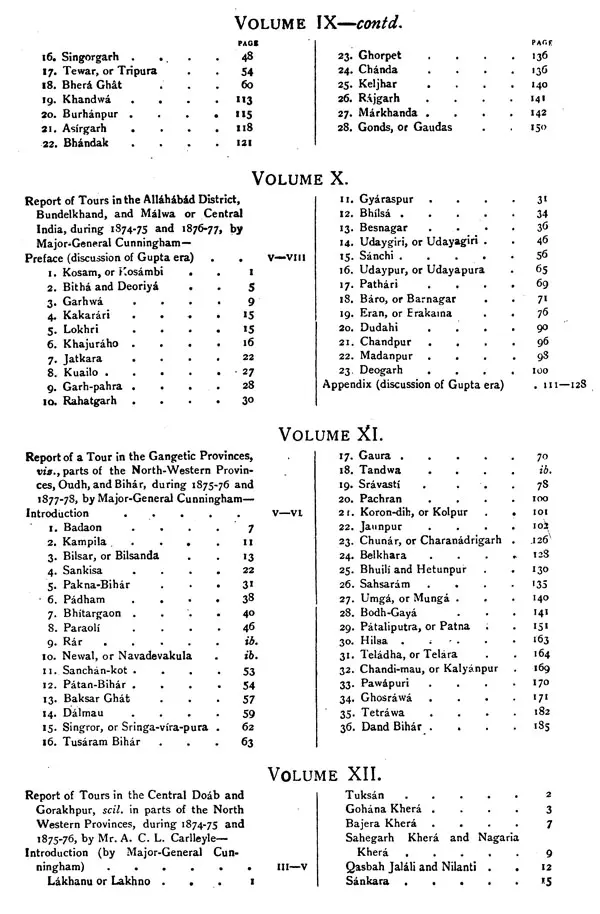

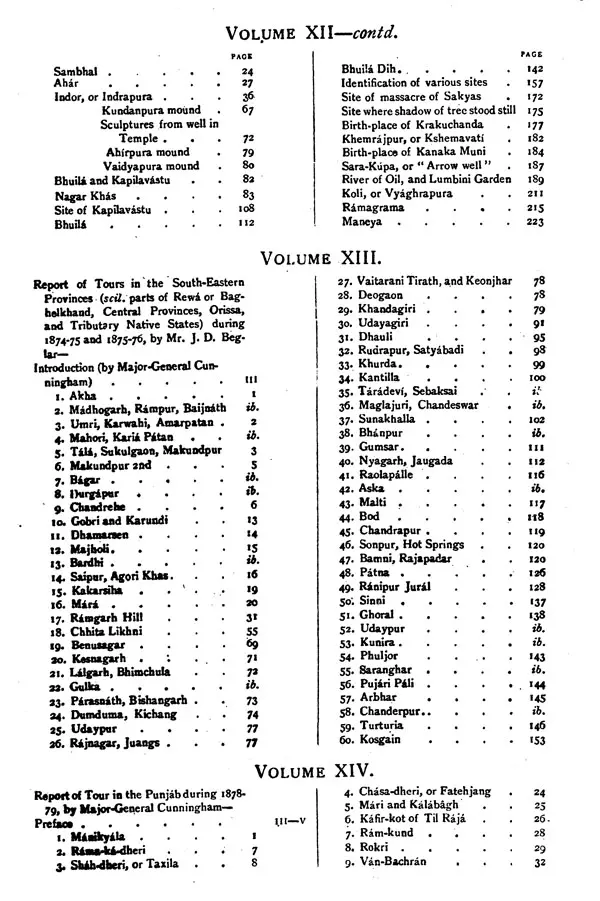

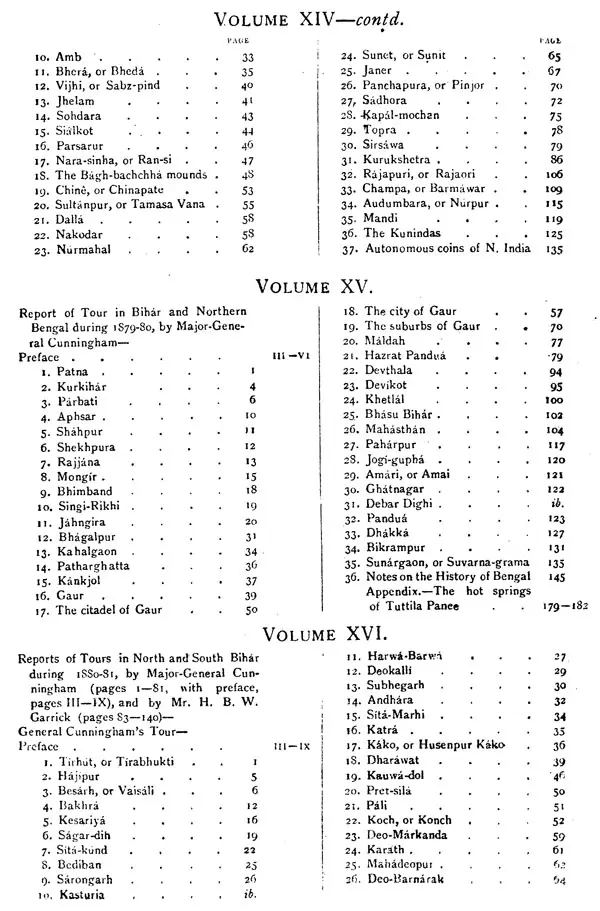

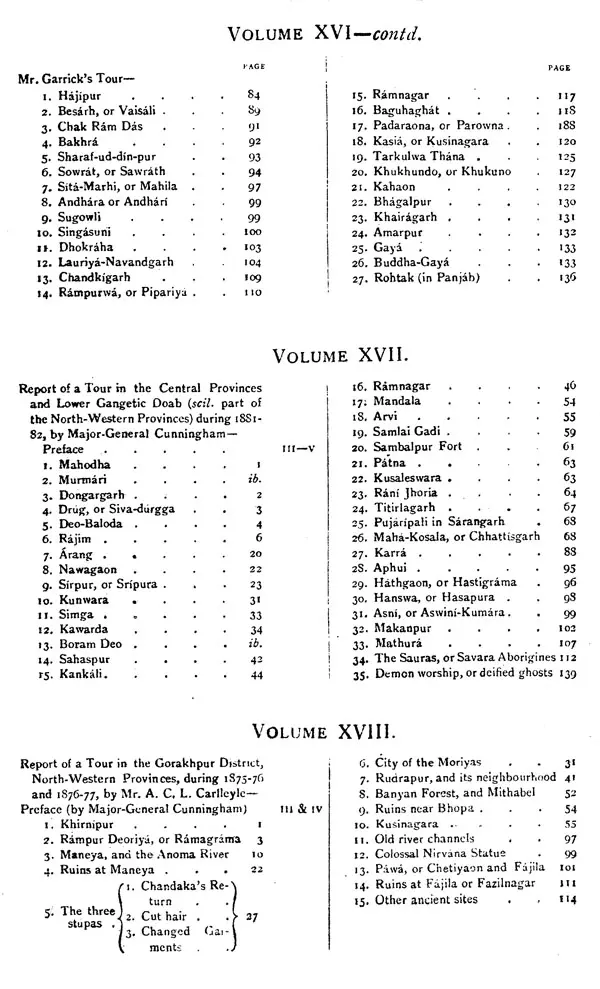

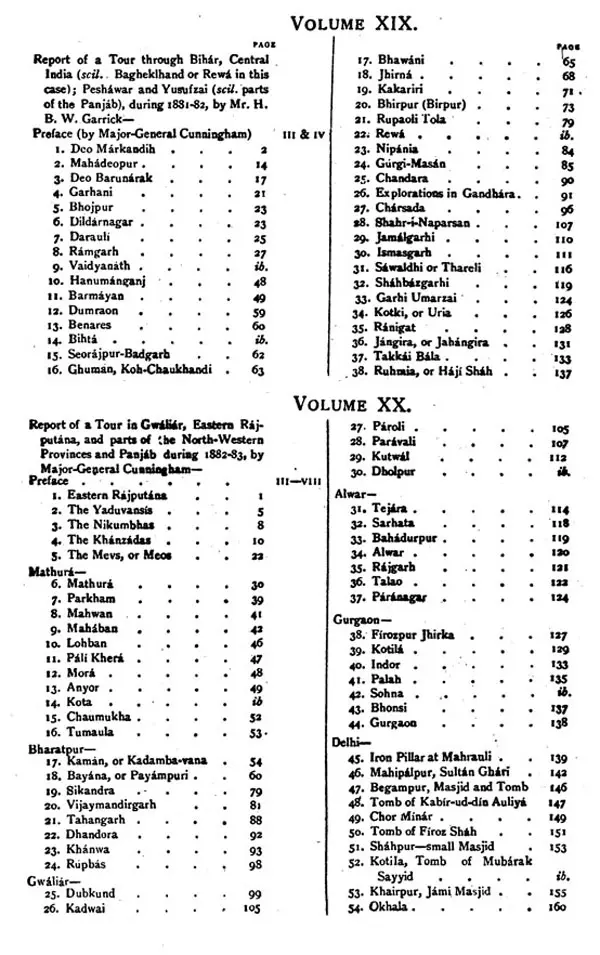

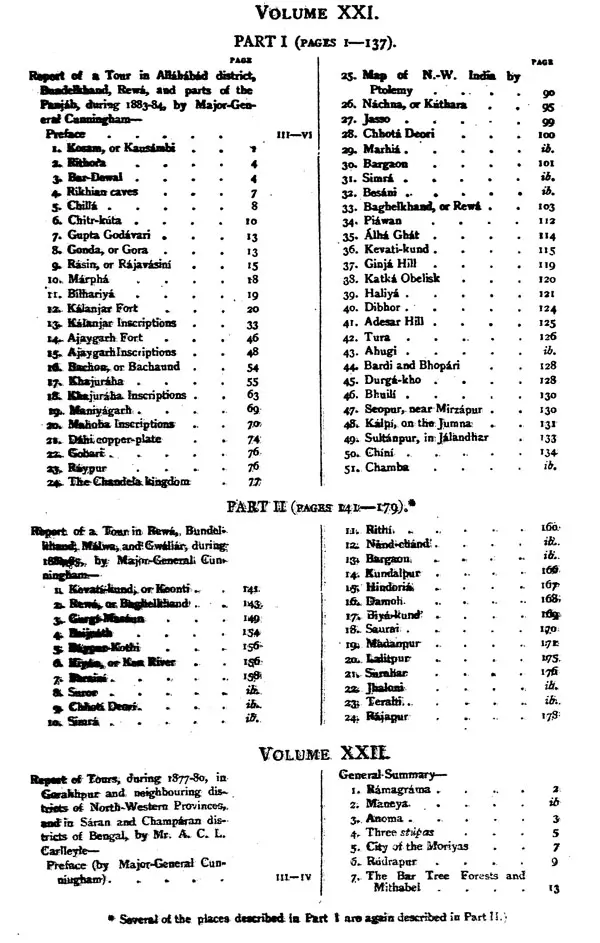

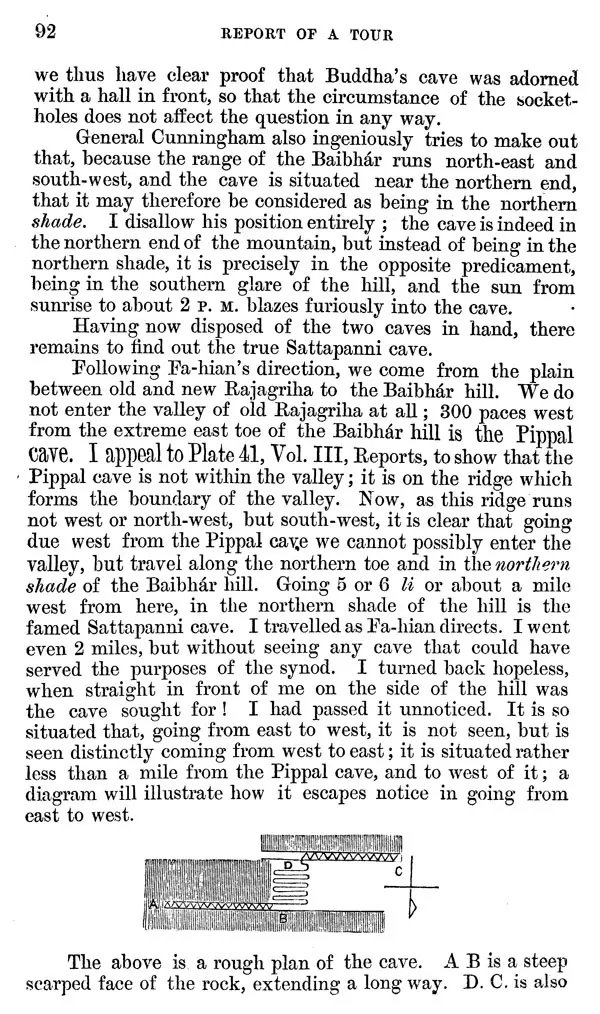

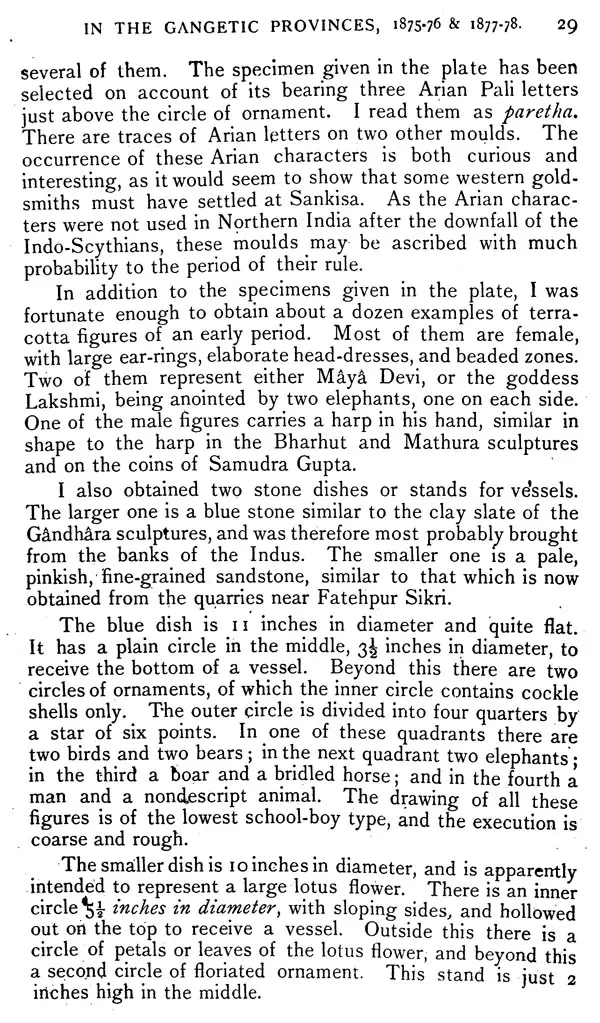

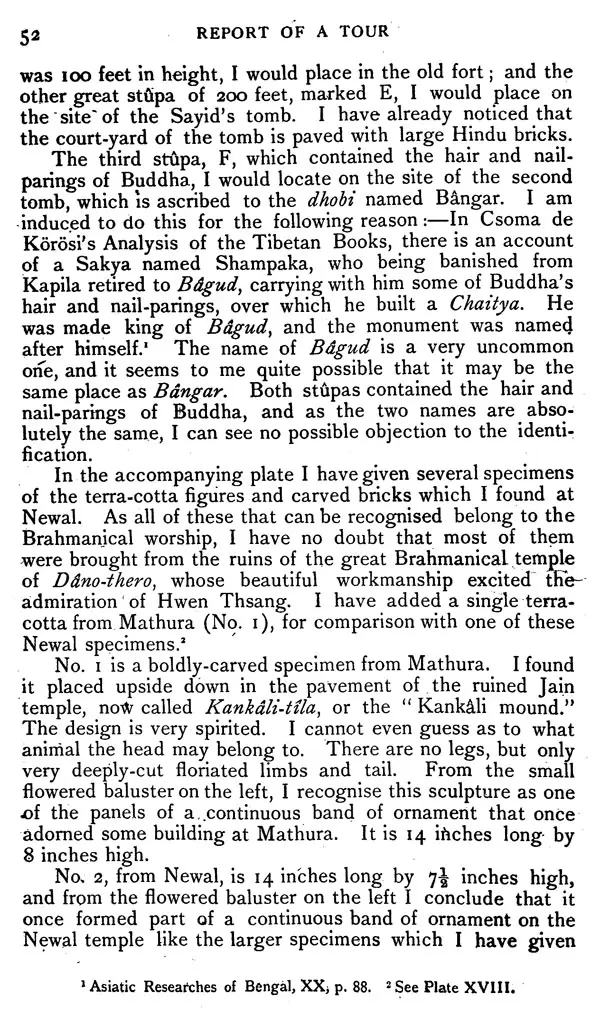

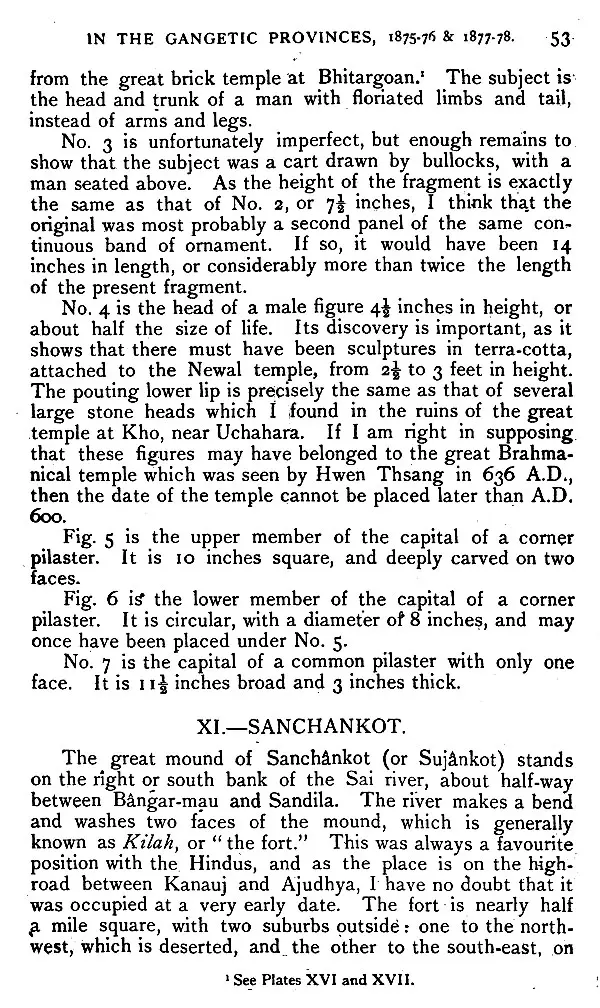

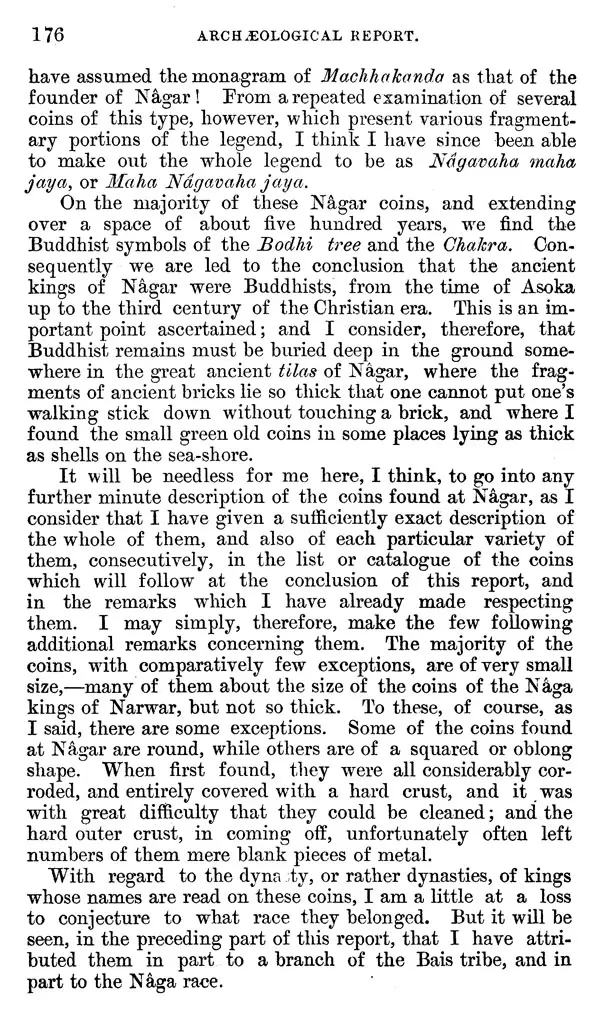

Book's Contents and Sample Pages